A thread has recently exploded when I posted about the Second Amendment and drawing the line between acceptable and unacceptable weaponry. On the thread, one particularly obvious common denominator sprung up with all of the gun advocates, the idea of “rights”:

A right is no less a right just because time goes by and technology changes.

I’m not an expert, but I believe the idea behind natural rights is that they can, and do exist outside of any social construct. For example, if attacked by a bear on a deserted island, one does not need law to grant her permissions to stick a spear into the bear’s belly. Nor does one need law to grant one the right to construct said spear.

People have the right to guns. Period.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,

that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,

that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

That you say the preceding is hogwash tells us all we need to know about you. You’ve no right to life according to your own statement.

Sorry, but no.

People have inalienable rights. No other person has the moral authority to grant you a single right.

In America we do have inalienable rights and it does not matter if the majority “feels” Citizens should not own certain weapons like fully armed Tanks and Machine Guns, government still will never have the legal,moral or the Constitutional power,nor the means of force, to ever disarm the American people of our right to be armed with modern weapons of war and self defense.That is an inalienable right and affirmed by the US Supreme Court!

Yes the right to be armed with modern weapons of war and self defense including guns is an inalienable right and affirmed as such by the US Supreme Court. See DC v. Heller,MacDonald v. Illinois ,Caetano v. Mass. and US v. Miller for factual references.

Gun rights are not negotiable.. We really don’t need to have a conversation about our rights to keep and bear arms. They’re rights. There’s nothing to talk about.

The 2nd Amend is a RESTRICTIVE admendment. It states such in the Preamble to Bill of Rights. the 2A does not grant nor convey any right, but RESTRICTS and PROHIBITS the government from infringing upon this enumerated,

pre-existing, God given right.

my rights don’t come from a document.

my rights were bestowed by my creator.

Americans have been exercising their rights for longer than we’ve been a country. longer than we’ve had a president or judges to tell us we couldn’t do so.

my right to self defense with arms is over 7,000 years old. It transcends government and in truth, the ONLY thing that the 2nd amendment does is limit the legal right of the government to interfere with my right to self defense.

when it stops doing that, I will change my government.

Inalienable rights are inherent to the human. No other human has any right or moral authority over another.

Those rights limit societal action.

I am admittedly going to include previous writing here in answering this before relating it to gun rights advocacy.

And, before any of the gun advocates from the previous thread or otherwise comment here, please can they think about not repeating the mantras above and establish what human rights are, how abstracta exist, where they exist, and how they are binding? I will not accept mere assertions.

Human Rights Don’t “Exist”

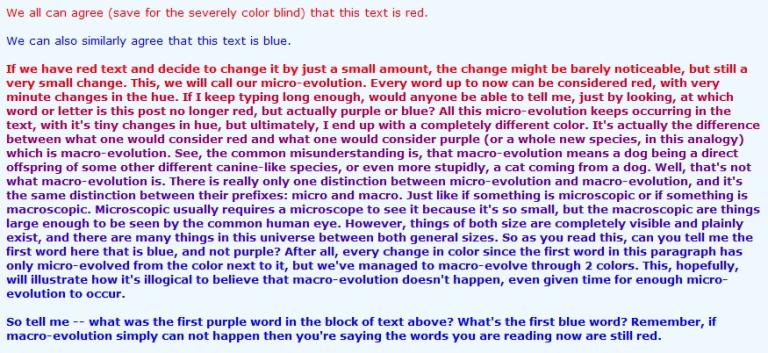

Human rights don’t exist. By this, I mean, as I so often state, they do not have ontic existence – they do not exist outside of our minds. Like all abstract ideas, for a conceptual nominalist (please read this, or linked posts below, to fully understand this post) like myself, the existence of such mental entities (labels, morality and so on) is entirely in our minds.

I, and most other humans, often talk about human rights as if they exist as objective entities. This is what the people above have done, and they can be excused for this as it is ubiquitous in our everyday language. However, this is lazy language. These ideas of rights, like any aspect of language itself, are arrived at by consensus. When we agree on the meaning of any word, we codify that by putting it in a dictionary.

Actually, it’s even more descriptive than that. When humans use language – words and whatever spelling we choose often enough – dictionary compilers recognise a certain level of frequency and deem a word and its spelling common enough to be included in the dictionary. For example, the word “gamification” recently made it in after being coined and utilised enough that it reached a tipping point of acceptance into codification.

It’s similar with abstract concepts like human rights. We think and observe and take part in society and then we make moral proclamations. I don’t know, something like these generic ones:

- The right to life

- The right to liberty and freedom

- The right to the pursuit of happiness

- The right to live your life free of discrimination

- The right to control what happens to your own body and to make medical decisions for yourself

- The right to freely exercise your religion and practice your religious beliefs without fear of being prosecuted for your beliefs

- The right to be free from prejudice on the basis of race, gender, national origin, color, age or sex

- The right to grow old

- The right to a fair trial and due process of the law

- The right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment

- The right to be free from torture

- The right to be free from slavery

- The right to freedom of speech

- The right to freely associate with whomever you like and to join groups of which you’d like to be a part.

- The right to freedom of thought

- The right not to be prosecuted from your thoughts

You might want to get more specific still. Like the right to bear arms and so on.

If I thought up these ideas but no one else did, or no one else agreed, they are not really human rights in any pragmatic sense, and they certainly aren’t universal. You could argue that there is a set of human rights that exist in some kind of ether or Platonic realm of truth. Perhaps in God as many commenters above specify. Of course, the Bible contravenes even some of the most basic human rights of, say, the UN (that seems infinitely more sensible and moral in its/their proclamations). So there is a problem of the observable data of the holy book of the Bible. Let’s scrap that book as a source of information about human rights.

Indeed, this whole post is equivalent to my writings on the ontology of morality since human rights are merely moral proclamations that many assume are objective and that somehow transcend time and culture.

Over time and thought and society, people tend towards agreement on moral matters. Unless you’re in America right now. In fact, the States is a great example of how, in reality, human rights are conceptual, how they aren’t written into the ether. The country is divided on abortion, and the right of a woman to their own body and the right to life of a foetus. I have discussed this, with connected ideas, in terms of personhood (as a word ascribed to a set of properties, and how this is subjective) in “What Is Personhood? Setting the Scene.“

Advocates, like those above, need to establish what abstract objects, under which rights fall, are; what they are made of and how they work. In short, they need to philosophically establish (Platonic) realism of sorts. Human rights sound lovely, but until we do something with them, they are meaningless, or they have no ramifications.

Human rights, therefore, are the philosophical underpinnings of moral thought that form the foundations to law. As we grow into a global society, the term “human right” takes on a more transcendent quality that dismisses borders in favour of the human race: it becomes a universal term. This is why it is often connected to the UN, an organisation that sets to unite the world and see humanity as one. This international law, it is hoped, somehow trumps the national and parochial laws of individual countries.

Legal Rights

Until we codify human rights into law – first into local and national laws, but more usefully into more universal, border transcendent laws – the thinking, the philosophy, behind those human rights is ineffectual and pragmatically impotent.

In short, “human rights” is a term that signifies “moral philosophy”, but the “right” part of it only means something when there is a legal framework to make the moral proclamation binding. We all know what a legal right is:

1a: a claim recognized and delimited by law for the purpose of securing it

b: the interest in a claim which is recognized by and protected by sanctions of law imposed by a state, which enables one to possess property or to engage in some transaction or course of conduct or to compel some other person to so engage or to refrain from some course of conduct under certain circumstances, and for the infringement of which claim the state provides a remedy in its courts of justice

2: the aggregate of the capacities, powers, liberties, and privileges by which a claim is secured

3: a capacity of asserting a legally recognized claim — compare LEGAL DUTY

4: a right cognizable in a common-law court as distinguished from a court having jurisdiction in equity

The law works to enable an entity within its jurisdiction the capacity to do, have or be something. Without that, you just have one person or people making moral claims to another person or people. Law makes these things binding.

To mention God, theists often claim morality is only binding when objectively embedded within the entity of God. Binding, though, simply means stuff happens when you don’t obey or adhere. Heaven and hell are mere promises from any given denomination of religion that believes in them, and for which there is approximately no evidence. And you can’t just claim that (human) rights are based in God: what does this actually mean. It is similar, if not identical, to saying God underwrites morality. So what? Even if we can know, somehow, that our understanding aligns with God’s, so what? Even if there is an objective ideal, is it knowable? And we still have to subjectively interpret it anyway. This is what Kant said about ding an sich – things in themselves – we cannot know them, at best we can interpret them in our own, subjective, phenomenal way.

This claim of rights being based in God is patent nonsense and is at very best a promissory note. Secular, legal rights that are binding in light of legal organisations such as law enforcement and jurisprudence, as well as prison services and suchlike, are far more tangible than what is claimed within the theistic notion of binding morality. There are real-world ramifications to not adhering to such rights as laid out in any given legal code.

In conclusion so far, then: set out your human rights as a philosophical endeavour (after arguing about them, and knowing that there will rarely be universal agreement) and then write these into law, preferably international law that transcends borders so that they become, as much as possible, universal. The reality will be that we arrive at these agreements by consensus. Hopefully, the consensus utilises the tools of logic and reason, observation and data analysis.

And the Second Amendment?

It’s pretty obvious how this all pertains to the Second Amendment – the right to bear arms. That is a mere declaration at a particular time, in a particular place, of a right. But it only means anything if it is interpreted in such a way that it is written into law and enacted. The claims above by the commenters on the other thread are meaningless. These rights, sadly for them, only exist in their heads. Well, actually no. They exist meaningfully in the laws of the US that still allow its citizens to bear arms. But no more than this. Laws can be changed; indeed, the Second Amendment and the Constitution as a whole can be ratified or rejected entirely. In my country, it’s wholly irrelevant.

The Constitution and Declaration of Independence are merely documents written in a particular time and a particular place. They are nothing more. The Consitution is only worth anything when valued by the people under whose influence it stands, and in the way it is interpreted and codified into law. The Constitution has been amended because it lacked completion at the time. It can always be amended. It is not concrete and is open to interpretation (often by the Supreme Court, but ostensibly by anyone).

Here are three quotes from the thread that sum up the views on the Consitution. As you can see, they are contradictory:

The Constitution is the FOUNDATION of law – a foundation upon which all laws rest…. Look to the Constitution – the foundation and authority for ALL laws.

The Constitution grants no rights. All the Constitution does is affirm the preexisting inalienable rights of all freemen and deny government the power to ever even infringe upon those rights! The interpretation that the Second Amendment protects an individual inalienable right has been affirmed as “settled law” and will never be changed. Just because you do not believe in inalienable rights does not mean millions of others do not believe in them and that they do not exist!

In America we have had inalienable rights recognized before the Constitution was even written. What rights do you think the Colonists had on April 19, 1775 when British General Gage tried to violate those rights by seizing the Arms owned by the Minutemen? Both the US Constitution and the Declaration of Independence affirm our inalienable rights as do the Constitutions of all 50 States. Inalienable rights are Birthrights that can never be taken away by government without due process.Your bizzarre claim about feeling you have the inalienable right to injure someone’s eyeball is both obtuse and a strawman’s argument.You have the right to injure yourself but not others.

The first comment claims the foundational aspect of the Constitution from which ALL laws supposedly find their authority. But then the third quote states that inalienable rights existed before the Consitution. These are directly opposed. At least one of these comments is obviously wrong.

So the problem here (one amongst many) is that, if there is a claim that rights exist prior to the Constitution, then the Constitution is nothing special – something of an interim document (given the Amendments). How do you know that the Consitution actually aligns with the “real”, pre-existing rights? This is exactly the same problem that exists with Divine Command Theory (DCT) – how do we know what God’s commands really are, and that we have aligned our rules with God’s? See the previous link to see how many of the issues with the Second Amendment advocates are involved in DCT.

Let’s see another few comments:

Next you will be claiming there is no inalienable right not to be enslaved! Read Locke and get educated! Humans are born with rights.

Slavery and gay rights are interesting examples. A few hundred years ago, American citizens would have argued that keeping slaves was a human right. Now, citizens have a right to same-sex marriage. I wonder how many of these same people would disagree with that human right. And with slavery, we can see adaption and change within our understanding and establishment of rights. We disagree and argue about rights precisely because they are not inborn, written on the “soul”, or whatever. They are conceptual and people require some philosophical discussion to either arrive at a consensus, or continue with disagreement. We disagree with what a hero might be – Gandhi, Rosa Parks, Luke Skywalker, Superman… The same scenario exists for any conceptual idea, rights included.

Every human being possesses fundamental human rights – rights that are NOT with the purview of government to limit. Even the Founders understood this…. The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the writings of the Founders are evidence [of this].

When pressed for evidence that rights are not merely conceptual, human inventions, the commenter gave human documents as his argument. Oh dear. When properly pressed, the commenters did one of three things:

- Continued to merely assert the primacy of rights without substantiation.

- Claimed they were natural rights/law.

- Claimed they were somehow embodied in God.

None of these positions cut the mustard. (See my extensive writings eviscerating natural law and morality as based in God).

We might agree, or not as the case may be, on the right to bear arms. But this right is utterly meaningless unless action about it takes place: when it is codified into law and enacted. Don’t go telling me the right to bear arms is inborn and inherent in us, or I will tell you we have the right to drive forklift trucks over babies, or forqwiblex on Tuesdays whilst elongating scenapsofils. Go prove those rights aren’t inherent. Or the right to marry someone of the same sex, or adopt within a same-sex relationship, or keep slaves, or keep Jews or immigrants in concentration camps. These are tricky territories where we have to use our finest philosophical training to navigate and argue over which rights obtain, and which don’t. And which are nonsense.

Inalienable Rights

The concept of “inalienable” rights is another thing that keeps coming up. This rather assertively means:

Personal rights held by an individual which are not bestowed by law, custom, or belief, and which cannot be taken or given away, or transferred to another person, are referred to as “inalienable rights.” The U.S. Constitution recognized that certain universal rights cannot be taken away by legislation, as they are beyond the control of a government, being naturally given to every individual at birth, and that these rights are retained throughout life….

These fundamental rights are endowed on every human being by his or her Creator, and are often referred to as “natural rights.” Only under carefully limited circumstances can such natural rights be taken away as people have the freedom to exercise them as they choose.

Of course, natural law is a thoroughly problematic position that falls apart precisely on concepts of realism, essentialism and (conceptual) nominalism (see related posts below and follow further links). The whole idea that humans are inborn with birthright rights is nonsense and a bare assertion at best. Where are they located? To the right of the pituitary glands? Below the kneecaps? What, as abstracta, are they made of?

Moreover, the rights as set out in the Constitution cannot be inalienable because they only exist in that fashion for citizens of the United States. They are not universal or transferable across borders or even time. The claim “The U.S. Constitution recognized that certain universal rights cannot be taken away by legislation, as they are beyond the control of a government, being naturally given to every individual at birth, and that these rights are retained throughout life” is obviously wrong, since they only apply to a small area of the world – the US – and can be removed or amended through democratic (or non-democratic) means. They don’t apply to me, and nor do I want them all. The right to bear arms? Meh. I don’t want firearms in the UK. I have not seen a gun in public for something like 15 years when I saw some armed police once, and that is the sort of society I prefer. I prefer the right not to have citizens around me armed.

When rights overlap and contravene other rights, which rights win? These issues cause endless debates because there is no objective list of evaluated rights that prioritise one above another. I can make up all sorts of rights and claim they are universal, embodied in God, inherent in humans and all such other nonsense. But claiming so does not make it so and does absolutely nothing to show how it could be so.

The language of rights and inalienable rights is everywhere, but it doesn’t make it cogent or objectively true as an idea. Because abstract ideas do not have objective, ontic existence. Unless these people can show me otherwise. Show me that if all sentient creatures, all humanity were to die, and with it, all concepts and ideas, the right to bear arms would still exist. Out there. Somewhere. In some Platonic aether.

Until they establish this, the 1000 comments on that other thread are wasted and meaningless; philosophical castles in the air, built with no foundation whatsoever. (N.B. Assertions do not make foundations).

RELATED POSTS: