At first glance, books about religious magazines should not be especially interesting, yet I find them rather irresistible. As a graduate student, I remember being very impressed by Mark Hulsether’s fine study of Reinhold Niebuhr’s Christianity & Crisis. Now, I’ve just finished reading Elesha Coffman’s outstanding history of The Christian Century and the Rise of the Protestant Mainline.

Rather than a formal review, here are a few bullet-point thoughts:

▪ As a historian, I love religious periodicals and newspapers (this explains the lack of resistance mentioned above). In fact, I cannot imagine studying what I have studied without them. Some of them are both entertaining and informative. If you are interested in early Mormon history, try the Nauvoo Neighbor or the short-lived and more acerbic Wasp. For evangelicalism in the 1970s and 1980s, look up the Wittenburg Door interviews.

▪ Coffman’s study benefits from two pieces of narrative drama. The first is the magazine’s constant struggle to stay afloat. The second is the Century‘s theological battles with a succession of opponents: its original Disciples constituency (over the issue of rebaptism for the unimmersed), longtime editor C.C. Morrison’s falling-out with Reinhold Niebuhr over matters of sin and politics, and the Century‘s clumsy attempt to parry the threat posed by Christianity Today and Billy Graham. Coffman certainly does not betray excessive sympathy toward her subject. While her overall assessment of the Century is quite positive, she puts the blame for the Century-Niebuhr feud squarely on the shoulders of Morrison and his associates, and she also finds the magazine’s attacks on Graham mean-spirited and counterproductive. In the matter of Niebuhr, the Century refused to concede that — in Niebuhr’s words — “liberalism had doctrines and presuppositions of its own.” Ironically, Niebuhr (who partly returned to the fold, a story Coffman might have told) led the magazine’s criticism of Graham, refusing to concede that Graham acted with at least as much ecumenism as his liberal detractors. And, in the end, “actual capital” trumped the Century‘s “cultural capital.”

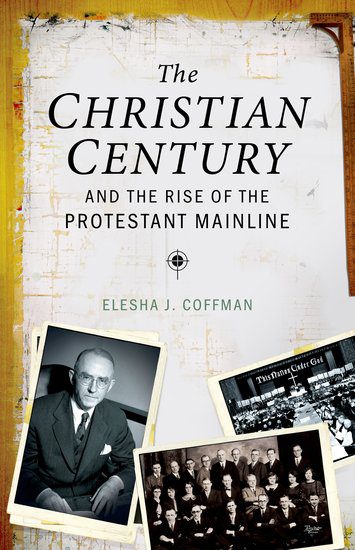

▪ What a great cover! Three photos: Morrison’s steely determination, a group of very non-threatening divinity school students, and an early  meeting of the Moral Majority. Just kidding on that last point. It’s a wonderful photograph of the constituting council of the National Council of Churches, meeting under an enormous banner raised over a cross, proclaiming, “This Nation Under God.”

meeting of the Moral Majority. Just kidding on that last point. It’s a wonderful photograph of the constituting council of the National Council of Churches, meeting under an enormous banner raised over a cross, proclaiming, “This Nation Under God.”

▪ Coffman observes that the term “mainline” “emerged as a religious descriptor” in 1960. Since the nineteenth century, it described the principal rail lines, especially in the Philadelphia suburbs. In 1960, a New York Times journalist used the term to describe “moderate and liberal” or “old-line” Protestantism, as opposed to conservative or fundamentalist extremists. As Coffman notes, the term connoted both something well-established and something moderate or middle of the road: “The mainline endeavored to be both, a leading tradition that also counted the majority of Americans as its followed. But its claim to the first set of characteristics was always stronger than its claim to the second.” In any event, Martin Marty contested the claim of Billy Graham and others to the term “evangelical” for a reason. Regardless of any baggage the term may now carry, it’s a much more positive and etymologically meaningful adjective to place in front of “Christian” than “mainline.”

▪ Partly in keeping with recent books by David Hollinger (review coming soon) and Matthew Hedstrom, Coffman seeks to counter the narrative of mainline decline. She does not argue for the mainline’s cultural influence, however, a very tricky matter to assess. I am not convinced that there is much “evidence of the mainline tacking from the left toward the theological and political center” (at least not the political center), but there has been a “churchly” and liturgical turn that distinguishes today’s mainline from its early and mid twentieth-century counterparts. She suggests that it is easy to overstate the mainline’s institutional decline and underestimate its resources. My hunch is that she is correct, though I would have enjoyed it had she fleshed out this ideas more fully in her conclusion.

▪I am not well positioned to reflect on the future of religious periodicals, which face struggles similar to those of other journals and newspapers. I do feel badly for the future historians who have to figure out how to pinpoint the opinion makers of twenty-first century religion and their constituencies. They will miss the heyday of religious periodicals.