While he tends his father-in-law’s sheep, as recorded in the Book of Exodus, Moses sees “the angel of the LORD … in a flame of fire out of a bush,” which burns but is not consumed. When Moses looks at the Bush, God calls to him, orders him to remove his shoes, announces himself as the god of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and promises to deliver the Israelites out of bondage in Egypt.

As far as Moses is concerned, the bad news is that God has tapped Moses to help bring about his people’s liberation. Moses foresees that when he tells his fellow Israelites that the God of their ancestors has sent him, they will want to know this god’s name. After some back-and-forth, God tells Moses that his name is יהוה (yhwh). This, known for its four letters as the Tetragrammaton, mean something along the lines of, “He who is.”

Surely, one might ask, did the people not already know the name of their God? After all, the Hebrew יהוה appears as early as the second chapter of Genesis. Back to Moses. In the sixth chapter of Exodus, God clarifies matters: “I am יהוה. I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai, but by my name יהוה I did not make myself known to them.” Thus, same God, new name.

Around the advent of Judaism’s Hellenistic era, Jewish translators of the Hebrew scriptures rendered יהוה as kurios or ho kurios, thus as “Lord” or “the Lord.” Jews increasingly forbade the pronunciation of the divine name, replacing it with the euphamism adonai (Lord).

In his Tetragrammaton: Western Christians and the Hebrew Name of God, Robert J. Wilkinson discusses the history of the divine name among both early Christians and among Western Christians from the middle ages through the seventeenth century. It’s a fascinating history, little known among contemporary Christians.

Wilkinson explains that while the Tetragrammaton makes no explicit appearance in the New Testament or in most other early Christian writings, the Hebrew name יהוה was “central in the developing Christologies of the early Christians.” Still, knowledge of the Tetragrammaton vanished in most Christian communities. “One should not underestimate Christian ignorance of Hebrew” during the early middle ages, quips Wilkinson. Instead of a “name,” Christians encountered “an authoritative self-description of God as the One Who Is.”

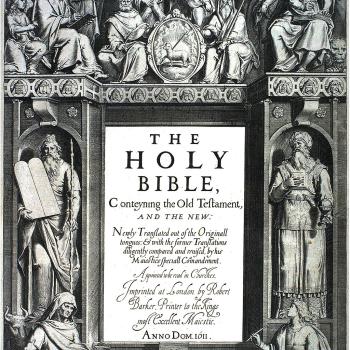

Eventually, Western Christians rediscovered the Tetragrammaton through the Hebrew Masoretic text (and sometimes through traditions of Jewish mysticism and magic). An amalgamation of the consonantal יהוה with the vocalization of adonai led to the “distinctly Christian ‘Jehovah,'” which took root in some European translations of the Old Testament (such as Tyndale’s 1530 Pentateuch) and in hymnody. Tyndale took care to inform readers. That “as oft as thou seest LORD in great letters (except there be an error in the printing) it is in Hebrew Iehouah, thou that art or he that is.” Jehovah appeared in most English translations over the next century, including in the 1560 Geneva Bible (as Iehouah) and occasionally in the King James.

Also, the Hebrew הוהי began to appear in Western art. Many Protestants disliked anthropormorphic depictions of God and found the Tetragrammaton an appropriate substitute. For example, authorities had יהוה painted over an image of God the Father in Lucas van Leyden’s Last Judgment triptych.

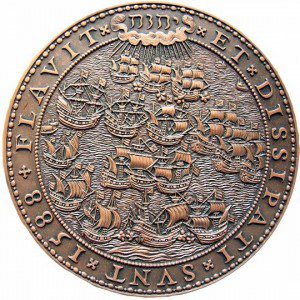

Wilkinson includes the image of a Netherlandish medal celebrating the 1588 defeat of the Spanish Armada. The inscription reads: “Flavit יהוה et dissipati sunt” [יהוה blew and they were scattered].

On altarpieces, church buildings, and elsewhere, European Christians saw יהוה, the Hebrew divine name for God.

There is much else in Wilkinson’s book, which features very careful reading of Jewish (including kabbalists) and Christian (Catholic and Protestant) sources over the span of many centuries. As Wilkinson thoughtfully concludes, “two traditions — that of the named God of the Hebrew Bible and that God as being — remain still in tension if not competition.”

For Christians, the Tetragrammaton provokes big questions. What does יהוה mean? What does it mean for God to have a name? How was it pronounced? Is it a personal name or a statement of God’s essence? Should humans pronounce it? Wilkinson does not provide answers to the latter two questions, but he expertly places all of these questions in the context of two thousand years of fascinating history.