While some of my colleagues here have written excellent examples of the genre, I’ve never had much desire to write a biography. In fact, it had been a few years since I’d even read such a book.

While some of my colleagues here have written excellent examples of the genre, I’ve never had much desire to write a biography. In fact, it had been a few years since I’d even read such a book.

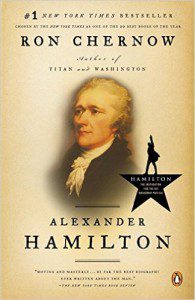

But then a road trip that included numerous plays of the Hamilton soundtrack convinced me to download the Kindle version of the Ron Chernow biography that inspired Lin-Manuel Miranda to write a hip-hop musical about America’s first treasury secretary.

And now, having just finished one writing project, I find myself pitching biography proposals to publishers.

The first idea was deemed too obscure. The second subject was deemed too, well, alive.

But then an editor suggested another name. Not obscure. Not alive.

And not someone I like all that much.

* * * * *

Frankly, I was almost relieved to have my first two pitches batted away. I had feared that I would be too sympathetic to the subjects — whom I largely admired and whose lives clearly influenced and (in some ways) paralleled my own.

And that seems like a common concern among historians who decide to try their hand at biography. For example, on a recent episode of his Way of Improvement Leads Home podcast, John Fea confessed that he was troubled that one reviewer (perhaps someone who, like John, used to blog here) called his 2008 biography of Philip Vickers Fithian “a deeply sympathetic portrait.” Said John:

And that seems like a common concern among historians who decide to try their hand at biography. For example, on a recent episode of his Way of Improvement Leads Home podcast, John Fea confessed that he was troubled that one reviewer (perhaps someone who, like John, used to blog here) called his 2008 biography of Philip Vickers Fithian “a deeply sympathetic portrait.” Said John:

While I generally liked Philip Vickers Fithian and could relate to his life as a first-generation college student… I wondered if I was too sympathetic to Fithian and his story. Did my sympathy cloud my historical judgment? Did I write with enough critical distance, or did I seem like a Fithian fanboy?

“Doesn’t this border on hagiography?”, John worried, referring to the genre of “idealized biography, such as those written about saints and founding fathers” (as producer Drew Dyrli Hermeling defined the term earlier in the episode) that is now abhorred by Christian historians like John and me — and still popular with many Christian readers.

* * * * *

That will not be a problem if I end up pursuing the editor’s suggestion and try to tell the story of a more controversial figure who left behind a rather ambivalent legacy. Instead, I’ll face a different problem, one I framed last year in this way:

History… is not just the marshaling of data (quantitative or qualitative), but the interpretation of evidence to advance an argument. And, often, an argument about someone — their behavior, their decision making, even their character. In that sense, when historians write history, they are engaging in a potentially aggressive act, struggling with another person for power over the meaning of the past.

Biography, too, can be a “potentially aggressive act.” As Beth Barton Schweiger admitted (in a book co-edited by John), “I can use the people I encounter in the archives without their consent for my own purposes, for my own pleasures, for my own professional gain. The dead languish without defense in my books; I can even silence them with their own words.” (Which suggests one reason why it’s trickier to write a biography of someone still living.)

It’s certainly possible that historians and biographers — in the words of a Jill Lepore essay that John mentioned in his podcast — can “love too much,” using their abilities to paint a too-charitable portrait of the dead. But love, in Schweiger’s view, remains a core virtue for historians who follow the teachings of Jesus, and perhaps a check on the temptation to abuse our power as biographers. If nothing else, it suggests that we ought to empathize, even with the least likable, most controversial subjects.

* * * * *

But as Andy Seal pointed out recently (in a pre-election blog post thinking ahead to how historians might look back at Donald Trump and his supporters), there is a fine line “between empathy and exoneration.”Aren’t there times when a historian ought to engage in biography as an act of aggression, and make meaning of a life in a way that the subject herself would no doubt reject?

I thought of something like Seal’s empathy/exoneration distinction last month while reading the eminent Civil War historian James McPherson assess Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Early on in Embattled Rebel, McPherson makes clear that he means to treat as empathetically and fairly as he can a person he doesn’t especially like, a man who did more than anyone to advance a cause McPherson despises:

My sympathies lie with the Union side in the Civil War. The Confederacy fought to break up the United States and to sustain slavery. I consider those goals tragically wrong. Yet I have sought to transcend my convictions and to understand Jefferson Davis as a product of his time and circumstances. After spending many research hours with both Lincoln and Davis, I must also confess that I find Lincoln more congenial, interesting, and admirable. That is another reason to avoid comparisons between the two men in a book about Davis as commander in chief. I wish not to be influenced by personal likes or dislikes. (p. 5)

In his acknowledgments, McPherson closes by thanking his wife Patricia, who “tolerated my preoccupation with Jefferson Davis, who is not her favorite historical character. But she recognizes that we cannot understand the Civil War and its meaning without coming to terms with the Confederate as well as the Union commander in chief” (p. 254).

Embattled Rebel is not exactly a biography. It picks up Davis’ story just before the beginning of the Civil War, only flashing back to earlier moments in his life when it helps McPherson accomplish his narrowly defined objective: to evaluate Davis “as a wartime commander-in-chief” (just as he had previously done with Davis’ opponent to the North). But that framing device itself may point back to the empathy/exoneration problem.

It’s not that McPherson entirely avoids Davis’ views on slavery and race, nor the Confederacy’s treatment of African Americans. But those topics only arise as they pertain to the war effort. For example, McPherson notes that enslaved labor freed up white workers to enlist in the military (and acknowledges that Robert E. Lee’s forces made the enslavement of free blacks an objective in invading Pennsylvania), but he dedicates far more time to Davis’ last-ditch, reluctant embrace of a proposal to free slaves willing to fight under the Stars and Bars.

Even within the stated confines of McPherson’s project, University of Pennsylvania professor Steve Hahn thought that “More space might have been devoted to the issue that hung over everything — slavery — and how it influenced Davis’s command.” In an otherwise glowing review, Hahn allowed that “it would have been helpful to learn more about the impact of slave rebelliousness behind the lines or how the demands of fighting to protect a slave society gave shape to the dynamics of command.”

And by limiting the scope of his interpretive question, McPherson also avoided dealing with a larger question: what limits should bound our empathy for a man who fought strenuously and unapologetically for the cause of white supremacy?

* * * * *

In any event, McPherson reports that “I found myself becoming less inimical toward Davis than I expected when I began this project. He comes off better than some of his fellow Confederates of large ego and small talents who were among his chief critics. I had perhaps been too much influenced by the negative depictions of Davis’s personality that have come down to us from those contemporaries who often had self-serving motives for their hostility” (p. 5).

Which points to another problem for biographers… While Davis was scapegoated by Confederate critics like vice president Alexander Stephens and General Pierre Beauregard when they wrote their postwar memoirs, he was hardly a passive spectator in the framing of the Lost Cause. His two-volume history of The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government came out in 1881, and his wife Varina completed his memoir in 1890, a year after his death. Both are among the many sources McPherson consulted for his research.

So if I do take on a project like the one proposed to me, I’d need to bear in mind that I’d be writing a biography of someone who was well aware of his place in history. Not entirely defenseless, people like him and Davis consciously sought to shape their legacies in ways that would survive them. They are not merely objects of historical analysis; even in death, they remain active interpreters of their own lives.

Coda: In the recent PBS special on Hamilton’s America, it was striking to hear Miranda describe his encounter with a Founding Father who has been dead for over two centuries: “I feel like Hamilton reached out from history and wouldn’t let me go until I told his story.”

To an even greater extent than Varina Davis, Eliza Hamilton advocated for her understanding of her husband’s legacy — a point made in the show’s aptly titled closing song, “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story.” If you’re interested in this question of legacy, see the full-on Hamilton post I shared at my own blog in September.