OXFORD — “By 1914,” observed Paul Fussell, “it was possible for soldiers to be not merely literate but vigorously literary.” So not only are students on our World War I travel course reading healthy amounts of poetry and prose as they seek to understand the people who fought the Great War, but we spent yesterday — our second-to-last in England — on a kind of literary pilgrimage.

When I was designing the course, I gave a moment’s thought to the idea of taking a train to Edinburgh, Scotland, where one can visit a small museum dedicated to the great war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, who got to know each other while convalescing from shell-shock. But that’s an awfully long way to go to see a hospital that’s no longer there.

And Bethel students’ reading tastes being what they are, I could hardly deny them the pleasure of visiting Oxford, the place where both Lord of the Rings and The Screwtape Letters were written. Fortunately (for the design of this course, not for these authors’ own well-being), both J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were themselves veterans of the Western Front.*

Tolkien, older than his future friend by nearly seven years, entered military service first, arriving in France in June 1916 — not quite three months after getting married and mere weeks before the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. “Junior officers were being killed, a dozen a minute,” he remembered. “Parting from my wife then… it was like death.” And while he suffered a severe case of the lice-born ailment known as “trench fever,” Tolkien survived the war. All but one of his best friends, he later recalled, did not.

Several commentators have detected the influence of Tolkien’s time on the Western Front in his best known work, the Lord of the Rings trilogy, particularly in two landscapes: cratered Mordor and deforested Isengard. But Joseph Loconte, author of a new book on Tolkien and Lewis, found the war contributing still more fundamental themes to those books:

The heroism of Tolkien’s characters depends on their capacity to resist evil and their tenacity in the face of defeat. It was this quality that Tolkien witnessed among his comrades on the Western Front…. Beside the courage of ordinary men, the carnage of war seems also to have opened Tolkien’s eyes to a primal fact about the human condition: the will to power. This is the force animating Sauron, the sorcerer-warlord and great enemy of Middle-earth….

Good triumphs, yet Tolkien’s epic does not lapse into escapism. His protagonists are nearly overwhelmed by fear and anguish, even their own lust for power. When Frodo returns to the Shire, his quest at an end, he resembles not so much the conquering hero as a shellshocked veteran. Here is a war story, wrapped in fantasy, that delivers painful truths about the human predicament.

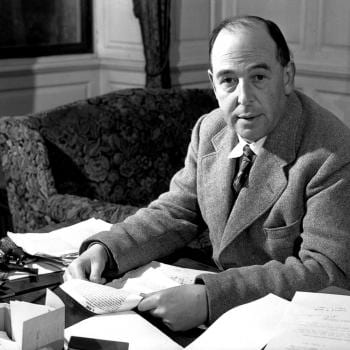

The influence of the war on Lewis is simultaneously harder to discern and potentially more significant. Unlike most of his peers, Lewis did not rush into military service. In 1916 he began his studies in an Oxford that was home to more convalescing soldiers than students. “Accordingly I put the war on one side to a degree which some people will think shameful and some incredible,” recalled Lewis. “Others will call it a flight from reality. I maintain that it was rather a treaty with reality, the fixing of a frontier. I said to my country, in effect, ‘You shall have me on a certain date, not before. I will die in your wars if need be, but till then I shall live my own life. You may have my body, but not my mind. I will take part in battles but not read about them.'”

After being conscripted, Lewis left Oxford in late 1917 and arrived at the front itself early in the last year of the war. Like Tolkien he contracted trench fever; unlike Tolkien he returned to the front and was gravely wounded in the spring of 1918, during the last great German offensive of the war (which nearly broke through to Paris and ended the war before American troops could arrive in sufficient numbers to make much difference).

Lewis, who would not turn 20 until after the Armistice, was a victim of what Americans now call “friendly fire.” An English shell landed short of its mark, and the young officer was hit with three shards of shrapnel, one of which pierced his left lung. It also killed his closest friend, an officer named Laurence Johnson. “I had him so often in my thoughts,” Lewis later wrote later to his father, “that I can hardly believe he is dead.” Also dead was a sergeant named Ayres, who had taken the overwhelmed lieutenant under his wing. “I was a futile officer,” Lewis admitted, “a puppet moved about by him, and he turned this ridiculous and painful relation into something beautiful, became to me almost like a father.”

Lewis managed to crawl to safety and was sent home to recover. After the war he resumed his studies at Oxford and eventually become one of its leading lights, teaching for many years at Magdalen College.

As he took us to visit Magdalen yesterday, our Oxford guide told us that WWI “doesn’t seem to have made a great impression” on Lewis – judging, at least, by how little he wrote about.

But the truth is probably more complicated.

Baylor professor Alan Jacobs, in his wonderful biography, The Narnian, observes Lewis’ obvious familiarity with the emotions and confusion of warfare — even when his literary battles, as in the Narnia books, couldn’t be less like the way of war in France, 1918. But he’s at least as interested in Lewis’ reluctance to talk about his experience of war:

It is hard to know how much these descriptions owe to Jack’s [Lewis’ nickname] own experience as a soldier, but certainly they mesh with what many soldiers of the Great War said or wrote about their time at the front…. In his letters Jack wrote very little about his battlefield experience: in the rougher periods there was no time, and all he could manage were scrawled notes telling his father that he was alive; in freer times—most of which were spent in the military hospitals at Le Tréport and Étaples—he chose to describe primarily whatever he was reading, as he had always done before…

Nor does Lewis go into detail in his memoir, Surprised by Joy, with one striking exception:

But for the rest, the war—the frights, the cold, the smell of H.E. [High Explosive], the horribly smashed men still moving like half-crushed beetles, the sitting or standing corpses, the landscape of sheer earth without a blade of grass, the boots worn day and night until they seemed to grow to your feet—all this shows rarely and faintly in memory. It is too cut off from the rest of my experience and often seems to have happened to someone else. It is even in a way unimportant.

Jacobs draws two equally plausible conclusions from this statement. First, that Lewis was consciously taking a path other than that pioneered by literary veterans like Brittain and Robert Graves (Good-Bye to All That), whose highly public remembering may have seemed to Lewis as tending “to overemphasize their misery.”

But second, Jacobs suspects that Lewis wasn’t being fully honest with the reader — or with himself. From other letters we know that, while recuperating from his wounds, Lewis suffered “nightmares—or rather the same nightmare over and over again.” And over two decades later, when a friend wondered if he would put on a uniform again at the onset of World War II, he replied, “I am too old. It [would] be hypocrisy to say that I regret this. My memories of the last war haunted my dreams for years.”

But Loconte concludes that “the sorrows of war did not ultimately blacken Lewis’s creative life.” He even speculates that the wounded officer’s journey from the front to a London hospital inspired not only Narnia, but helped plant seeds for Lewis’s later conversion to Christianity:

It seems likely that the simple pleasure of a train ride through the English countryside, set against the dreariness and horror of war, created for Lewis a powerful experience of joy: a sensation so compelling that it undermined his materialist outlook….

The experience appears to have wrought a change in Lewis—a small change, perhaps, but a permanent one. It quickened his belief in a spiritual, otherworldly source of natural beauty.

Adapted from an earlier post at The Pietist Schoolman

*It’s not just Inklings that took us to Oxford. While there, we also read two more excerpts from the most famous Oxonian memoir of the war: Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth. One of the few women of her time to study at Britain’s elite universities, Brittain arrived at Somerville College near the war’s beginning. That fall she wrote to her fiancé, poet (and new infantry officer) Roland Leighton: “I sometimes feel that work at Oxford, which will only bear fruit in the future and lacks the stimulus of direct connection with the War, will require a restraint I am scarcely capable of. It is strange how what we both worked for should now seem worth so little.” In the spring of 1915, she came back from break to find “an Oxford that now seemed infinitely remote from everything that counted.” After that term, she left to train as a nurse, hoping to maintain a vicarious connection to Roland — who would die in France at year’s end. After serving everywhere from the Mediterranean to the Western Front, Brittain returned to Oxford in 1919 and shifted her focus to modern history. Her Oxford-set first novel, The Dark Tide, came out in 1923, a decade before Testament of Youth.