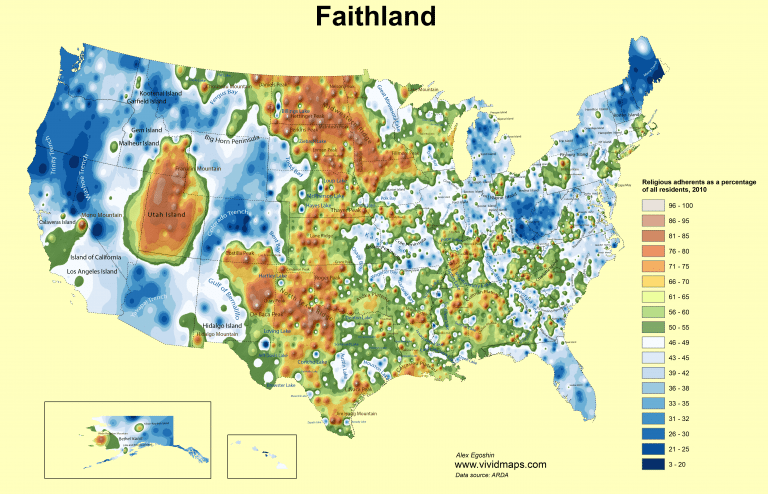

Did you see this map making the rounds a couple weeks ago? Using data from the 2010 U.S. Religion Census (via the Association of Religion Data Archives), creator Alex Egoshin constructed Faithland, a heat map of religious adherence, county by county, for the United States.

Egoshin came up with topographical names for blue patches of low adherence (bays, trenches, lakes, seas) and red spots of high adherence (islands, ridges, plateaus, peaks). For the most part, the results are unsurprising. Religious adherence is generally lowest on the two coasts and in the Mountain West — with the notable exception of “Utah Island.” Then there’s a mid-continental archipelago of high religious adherence in the Southeast and Great Plains. Beth and Philip, for example, teach in a part of Texas where 614.1 people per thousand are connected to almost 400 different congregations. And McLennan County ranks only 118th of that large state’s 254 counties!

But there are a couple of blue and red patches on the map that may make you pause and wonder. I’ll let someone else explain what Egoshin calls the “Kentucky Trench.” I was most interested in his “Midwestern Ridge,” comprised of North Dakota, most of South Dakota, and their borderlands.

Just how religious is this place where the Upper Midwest and Great Plains meet? Compare it to the aforementioned “Utah Island.” According to the religion census, 77 American counties have higher adherence rates than the most religious part of Utah. Egoshin’s Midwestern Ridge accounts for 30 of them.

To help visualize this “ridge” in a different way, I created a Google Map that includes every county in the Dakotas — and those within 100 miles of those borders — where at least 85% of the 2010 population registered as an “adherent” of some sort in the religion census. Predominantly Catholic and Lutheran counties are yellow and red, respectively, while those where those two traditions share the bulk of adherents are orange. (Then there are a handful of green outliers that I’ll talk about below.) If you click on each tag, you’ll find the top three denominations for the county.

What unites this region? Besides being so heavily Catholic and Lutheran, how does it stand out from the rest of 2018 America?

- It’s rural: more than half of those 49 counties had fewer than 5,000 residents in the 2010 Census, and only seven have five figures. The largest city is New Ulm, Minnesota (pop. 13,522).

- It’s white: New Ulm is just one of the many German-American enclaves that dominate this region, with Norwegian-Americans the next biggest group. On average, these counties are 90% white, seventeen points higher than the national average.

- It’s aging: while the North Dakota oil boom seems to have changed this trajectory in several of these counties, even the most recent census estimate gives the average age of these Americans as 44.7 years — seven more than the nation as a whole.

- It’s Republican: the only place in this entire cluster that went for Hillary Clinton in 2016 is Rolette County, ND, which last voted for a Republican presidential candidate when Dwight Eisenhower first ran. Nearby Benson County is the only other where Donald Trump didn’t receive a majority — and he still won the county thanks to a strong third party number. On average, the Midwestern Ridge gave 70% of its votes to a GOP president who won 46% of the national popular vote.

But Rolette and Benson point out that this region may be less predictable than it appears. Both have American Indian majorities. (The former overlaps with the Turtle Mountain reservation; the latter with Spirit Lake.) The religion census doesn’t account for adherents of indigenous religions, but clearly we’re in a part of the country where Native American Christianity is unusually strong. More specifically, Native American Catholicism — 99.9% of the population of Rolette County is affiliated with one of its seven Catholic churches. (Five of them part of the St. Ann’s Mission, founded in 1885 to evangelize local Chippewa and Métis.)

And while this “ridge” is full of conservative religious white people, it’s notable how few of them are evangelicals (depending on what you do with Missouri Synod Lutherans, who rank third behind the ELCA and Roman Catholic church in many of these counties). There’s a smattering of Pentecostal, Holiness, and Baptist influences, but much more common are historic Catholic and mainline immigrant churches like the one in Hebron, ND where my wife’s late grandfather, an Evangelical & Reformed pastor, preached in both English and German. (To this day, German is the most commonly spoken second language in North Dakota.)

For all the northern European Catholics and Lutherans, the Dakotas and their borderlands are also home to several other religious groups. For example, 70% of the 2,982 South Dakotans living in Perkins County are Catholic or part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), but that county hosts a modest Church of God (Tennessee) congregation and nine other denominations (plus a small non-denominational church). Just sticking with the counties on my Google Map, you’ll find:

- Mormon meetinghouses in Carroll, IA, Gettysburg, SD, Pipestone, MN, and Plentywood, MT. (The census found about a hundred Latter-day Saints in the aforementioned Rolette County, but they need to drive about an hour to Rugby.)

- One of the 90 congregations making up the Apostolic Christian Church of America, in Lester, IA.

- A Unitarian Universalist church in Hanska, MN — founded by Norwegian immigrants who split from the local Lutheran church in 1881 and called as pastor the poet Kristofer Janson.

- Just over 300 Muslims — the only adherents of that religion reported in these counties — inhabit Calhoun County, IA.

- About a third of the 123 North American congregations in the Church of the Lutheran Brethren — a pietistic denomination whose lone seminary is in Fergus Falls, MN. Likewise, this region is a major center of the North American Baptists — and home of its seminary — another historically pietistic group whose early leaders included the father of Walter Rauschenbusch.

Dutch Reformed Christians (both RCA and CRC) predominate in the corner of South Dakota and Iowa that Egoshin calls “Sioux Ridge.” (Maybe Kristin can come back to this in a future post…) But even in Sioux County, IA — home to both Dordt College and Northwestern College — there’s a growing Latino population, now accounting for 1 in 10 residents. The only Sunday mass at Sioux Center’s largest Catholic church is in Spanish. The Evangelical Free church in Orange City has Spanish services on Sunday and Wednesday evenings.

Then there’s South Dakota’s Hutchinson County. Not only are Mennonites the single largest group (about 19% — historically, German-speakers from Russia), but it’s home to several other groups with Anabaptist roots: Mennonite Brethren, Missionary Church, and Evangelical United Brethren congregations, plus an Amish settlement and three of the region’s many Hutterite colonies. (I wish I knew who to credit for the map below — it’s certainly not my work.)

Now, there are obvious limitations to this data. First, it stops at the border. Six of the counties are on the 49th parallel, but I don’t know enough about Canada to know if the ridge is transnational.

Second, in several of these counties the number of adherents is greater than the actual population. I don’t know the religion census well enough to understand this problem, but I assume there’s a not insignificant degree of double-counting, especially in areas of high Lutheran adherence. For a time, at least, it was possible for a congregation to belong to both the ELCA and the more conservative movement known as Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ (LCMC). I wonder if that was still the case eight years ago…

Third, adherence is not the same thing as attendance. Or religiosity, or belief, or any number of other perhaps more relevant measures. For the 2010 religion census, the use of “adherents” was meant to provide “the most complete count of people affiliated with a congregation, and the most comparable count of people across all participating groups. Adherents may include all those with an affiliation to a congregation (children, members, and attendees who are not members).” There was a separate attendance survey, but I haven’t found those numbers for these counties. Still, I can easily imagine that there are plenty of churches in this demographic “ridge” where church membership or other affiliation is much higher than church attendance or participation.

All that said… I still wonder if the religion of this area gets the attention it warrants. I’ve written before that “overlookedness” is central to Midwestern self-identity, and that’s even more true of the two states that feature so prominently in Kathleen Norris’ “spiritual geography”:

Most visitors to Dakota travel on interstate highways that will take them as quickly as possible through the region, past our larger cities to such attractions as the Badlands and the Black Hills. Looking at the expanse of land in between, they may wonder why a person would choose to live in such a barren place, let alone love it. But mostly they are bored: they turn up the car stereo, count the miles to civilization, and look away.

Are scholars of religion much different? Or do they tend to look away from the Midwestern Ridge’s Catholics, Lutherans, and assorted others in their hurry to examine New England’s Puritans, the South’s Baptists, and California’s megachurches?

If I’m wrong, I’d very much like to be corrected. This isn’t my field, and I’d love to better understand the people living just to the west of me. So please share book and article recommendations in the comments section — or, if you’re from this part of Faithland, your own memories and observations about religion there. Thanks!