“There are a lot of theories,” wrote historian John Fea during the 2016 Republican primaries, “to explain why large swaths of evangelicals seem to like a narcissistic, vulgar, misogynistic, intolerant, and angry reality TV star who behaves like a school yard bully and has a temperament that is diametrically opposed to the meekness, humility and prudence necessary to lead the free world.” RNS published that piece on May 8 — exactly five months before 81% of the white evangelicals who voted cast their ballot for Donald Trump.

The day after Trump’s victory, Fea reposted the May RNS essay, which continued:

…as a historian it is also my job to take a longer view — to look deeper into the American evangelical past in search for answers. Is there something inherent within American evangelicalism, as it has developed over the decades, that has led so many born-again Christians to vote for Trump?

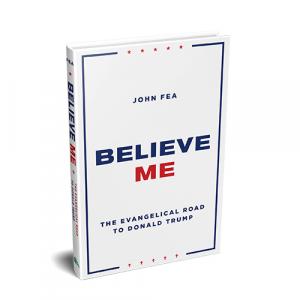

Fea has been asking that question ever since, with a fuller version of his answer arriving next week in the form of his accessibly ambitious new book, Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump.

Fea has been asking that question ever since, with a fuller version of his answer arriving next week in the form of his accessibly ambitious new book, Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump.

The title comes from one of Trump’s most popular campaign phrases — as in, “So let me state this right up front: [in] a Trump administration our Christian heritage will be cherished, protected, defended—like you’ve never seen before. Believe me.” So why would so many white evangelicals not only believe candidate Trump, but continue to believe President Trump, long after he had proved himself one of the most dishonest figures in American political history?

Some would say that evangelicals never really believed him — save when he promised to appoint the right kinds of justices and judges. (One campaign pledge Trump has amply fulfilled.) “I’m tired of seeing Evangelicals who voted for Trump slandered for choosing between the two major candidates they had,” wrote Ed Stetzer of Christianity Today the day Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch. “For many Evangelicals, it’s the Supreme Court, stupid.”

But if that’s true, why has white (but not non-white) evangelical support for Trump stayed so strong, long after Trump secured the desired SCOTUS appointment yet continued to reveal himself to be the racist, misogynist, and xenophobe Stetzer insisted was not attractive to evangelical voters?

Is it possible that evangelicals voted for Trump not in spite of evangelicalism, but because of it? Or at least, as Fea put it in that May 2016 post, are their factors inherent within their movement that would make American evangelicals support Trump, even to respond to him with something like belief? In Believe Me Fea identifies several such factors, in particular “the politics of fear, the pursuit of worldly power, and a nostalgic longing for a national past that may have never existed in the first place.”

To trace the origins of those impulses in evangelicalism, Fea points to some more recent developments. For example, most of the figures he has famously called “court evangelicals” (see ch. 4) are either veterans of the Religious Right of the 1980s and 1990s or rising leaders associated with the Prosperity Gospel and Independent Network Christianity. But it’s even more striking to realize, as you read Fea’s adroit survey of nearly four centuries of history (especially in ch. 3), how deeply rooted are the impulses of fear, power, and nostalgia in American evangelicalism. As Fea has written previously, historical thinking is especially sensitive to change over time, but we shouldn’t neglect the importance of historical continuity.*

Arguably, these aren’t the only continuities that explain white evangelical support for Trump. No book of this length is going to cover every potential answer to Fea’s basic question, but had he written more of his manuscript after the #MeToo movement erupted, I wonder if Fea wouldn’t have made more of gender. (“I love women,” Trump wants us to believe. “And you know what else, I have great respect for women, believe me.”) Fea notes in passing that early 20th century “fundamentalism relied heavily on strong, masculine clergymen,” without going on to ask if that reliance continues to the present day — and if it may have affected evangelical views of both Trump and his opponent: the first woman nominated by a major party.

Then there’s the problem of racism. In his mostly favorable review of Believe Me for Religion Dispatches, Greg Carey noted that the “question of race figures prominently in Fea’s analysis, but it does not rise to the level of the Big Three: fear, nostalgia, and power… Race proved one of the most decisive predictors of Trump support, and  white evangelicals were the most loyal Trump voting bloc of all.” Fea’s hopeful conclusion flows out of his experience on a Sankofa journey on the history of the civil rights movement, but Carey thinks that “the caution of [Fea’s] argument [on race] fails him,” since Believe Me doesn’t directly attribute white evangelical support of Trump to racial resentment or white supremacy.

white evangelicals were the most loyal Trump voting bloc of all.” Fea’s hopeful conclusion flows out of his experience on a Sankofa journey on the history of the civil rights movement, but Carey thinks that “the caution of [Fea’s] argument [on race] fails him,” since Believe Me doesn’t directly attribute white evangelical support of Trump to racial resentment or white supremacy.

But consider that Fea is not only writing about such Christians; he is writing to them, as one of them — something he has been doing for a decade now, through his Way of Improvement Leads Home blog (and podcast), numerous op-ed pieces, and books that make rigorous scholarship available to general audiences. In an interview with Publishers Weekly, Fea explained that

I chose a faith-based publisher because I wanted the primary audience of this book to be evangelical Christians who, perhaps voted for Trump, but are open to rethinking their decision—people on the fence, people who held their nose and voted for him and now regret it, or could be convinced it wasn’t the best idea.

Perhaps that makes it seem like he pulls his punches on an issue like racism. But I’d read Fea’s approach differently.

For example, in the first half of ch. 5, on Trump’s promise to “Make America Great Again,” Fea confronts evangelicals with the historical and theological problems inherent in the idea of America as a Christian nation. (Familiar territory for him.) Then while the rest of that chapter reveals the racist and xenophobic subtexts of Trump’s appeals to nostalgia, Fea holds back from indicting white evangelicals themselves. Instead, I think he trusts that such readers who have made it that far in Believe Me can make the connection themselves and question — maybe for the first time — just why they yearn to revive what Russell Moore dismissed as “the supposedly idyllic Mayberry of white Christian America. (“That world,” Moore continued, “was murder, sometimes literally, for minority evangelicals.”)

Maybe such readers won’t ask that question, or even read the book in the first place; since 2016 I’ve had my own doubts about the possibility of changing evangelical hearts and minds. But there’s some evidence even in recent weeks of conservative Protestants rethinking their commitment to a Trump-led culture war. And believe me, if any historian can succeed in getting American evangelicals to take an even longer, more honest look at themselves in the mirror of their own past, it’s John Fea.

*I still think Fea is right to push contemporary evangelicals to think about their connections with or echoes of earlier movements in American religious history. But there’s an argument to be made for discontinuity — e.g., sociologist John Hawthorne’s recent suggestion that “evangelicalism as a social movement doesn’t necessarily share a heritage with those early evangelicals. It became an entity unto itself in the 1980s with its own definitions and parameters.”