Perhaps you’ve heard.

One month ago, evangelical women “hit pause” on the culture wars.

It might surprise you to hear that this olive branch was extended in response to President Trump’s proposed Supreme Court pick. While many evangelicals were celebrating this victory, “evangelical women” raised a voice in protest. The strategy to dominate the court, they contended, “will result in a loss for the pro-life movement and for people of color sitting in the only growing segment of the evangelical church; evangelical churches of color.” In their press release, the authors of the manifesto pointed out that “abortion rates for American women have hit an all time low, but they’ve increased among poor women because economic hardship is the primary driver of abortion.” They asserted that “the way to reduce abortion is not through escalating culture wars but by reducing poverty.” They pointed to recent rulings that have “whittled away voting rights and desegregation,” and called for evangelical women to push back against this latest culture wars salvo.

By this point you’re probably wondering precisely which “evangelical women” are wanting to hit the pause button. The effort was initiated by Lisa Sharon Harper, formerly of Sojourners and author of The Very Good Gospel. The statement was signed by a number of other women, who added their own eloquent words of support: Jen Hatmaker, the Rev. Brenda Salter McNeil, Rachel Held Evans, Latasha Morrison, Maria-Jose Soerens, Belinda Bauman, Kathy Khang, Shannon Dingle, Christina Edmondsen, and D.L. Mayfield, among others.

As a historian of evangelicalism, though, I couldn’t help but wonder: For whom, exactly, do these women speak? And to whom? In other words, who are “evangelical women”?

I could have sworn Rachel Held Evans left evangelicalism a couple years back. And I thought Jen Hatmaker was on the outs, too. It wasn’t that either had renounced her faith, but each crossed lines that certain evangelical gatekeepers had drawn. Hatmaker, for example, had voiced her support for same-sex marriage, and in response, LifeWay Christian Stores refused to sell her books. It was up to her once loyal readers to decide: Were they with her or against her? Was she still one of them?

The election of Donald Trump, of course, prompted a slew of other evangelicals to voluntarily turn in their membership cards. At least for a time.

It is worth noting that a number of women “hitting the pause button” on the culture wars are women of color. In signing this document, they are staking a claim on “evangelicalism,” and reminding fellow evangelicals that what growth there is within American evangelicalism is happening within churches of color. And well they should. “Evangelical” beliefs—a belief in the authority of the Bible, in Christ’s atonement, in the importance of a personal relationship with Christ—are widespread among Black and Hispanic Protestants. And yet, as Melani McAlister, Jemar Tisby, and others have recently pointed out, “evangelicals of color” have an ambivalent relationship with evangelicalism. A recent NAE/LifeWay survey, for example, found that only twenty-five percent of African Americans who hold “evangelical beliefs” actually identify as evangelical.

Why is this?

This is not the case of a simple misunderstanding. Black Christians have long resisted embracing the evangelical label because it is clear to them that there is more to evangelical identity than rarified statements of belief. Anthea Butler, for instance, has decried evangelicalism’s “problem of whiteness.” Dierdre Riggs has called evangelicalism a “white religious brand.”

It’s worth remembering that the evangelical left more broadly has been contesting the Religious Right’s hold on “evangelicalism” for at least half a century. From “Evangelicals for McGovern” to the Rev. William Barber’s attempts to redeem “evangelicalism” from extremists, there is a long history of those who identify with the evangelical left attempting to call their sisters and brothers back to “true evangelicalism.”

But are those sisters and brothers listening? Do conservative evangelicals consider members of the “evangelical left” kindred spirits?

To be honest, as a close observer of American evangelicalism, I see little evidence that this is the case.

In fact, conservatives have been quick to ignore or dismiss progressive voices. The easiest way to do this is to define them out of the fold. Rachel Held Evans and Jen Hatmaker (and Rob Bell, for that matter) were quickly dispatched in this way. Often it happens with less fanfare. When Thabiti Anyabwile, a black Southern Baptist pastor, member of the Gospel Coalition, and staunch social conservative, recently cautioned his white evangelical brethren against selling out “brown and black lives” for a victory on Roe v. Wade, he was attacked as a “fake Christian pastor” who “does not represent Trump’s base or Christians.”

But this goes both ways. “Respectable” evangelicals, too, have sought to wield the definitional sword for their own purposes. Russell Moore led the charge during the 2016 election season, placing a good chunk of the blame on the media for conflating true evangelicals with imposters: “Many of those who tell pollsters they are ‘evangelical’ may well be drunk right now, and haven’t been into a church since someone invited them to Vacation Bible School sometime back when Seinfeld was in first-run episodes.” Moore also blamed evangelicals themselves, complaining that the word had been “co-opted by heretics and lunatics.” But he insisted that these distortions shouldn’t be confused with the true nature of evangelicalism.

Evangelical historian Tommy Kidd echoed Moore’s complaint. He lamented that a “pop culture” definition of evangelical had usurped a proper historical and theological one, giving an entire generation of Americans “the wrong idea about evangelicalism.” As a result, we’ve ended up with a large number of “supposed evangelicals” who really have no clue about “the formal definition of ‘evangelical.’” They think that because they watch Fox News, respect religion, and vote Republican, they must be evangelicals.

Tim Keller tried to split the difference, contrasting “big-E Evangelicalism”—the predominantly white, highly politicized, hypocritical evangelicalism—with “little-e” evangelicalism—a global, racially diverse, and politically unaffiliated religious movement. He regretted that the media only ever seemed to pay attention to the one, to the neglect of the other.

Such attempts by “establishment evangelicals” to rehabilitate “evangelicalism” in the era of Donald Trump haven’t gone unchallenged, however. Critics have attacked from both sides. In their book The Faith of Donald J. Trump, David Brody and Scott Lamb chide “evangelipundits” who worried that Trump supporters were tainting “the brand identity of ‘evangelicalism,’” and insist that church-going evangelicals provided the critical support that secured Trump the nomination, and then the presidency. Stephen Strang, author of God and Donald Trump, took things a step further. In an interview with the New York Times, he took issue with those who worried about Trump tarnishing the evangelical brand, and suggested that they were “not really believers—they’re not with us, anyway.”

Meanwhile, over at Religion Dispatches a few months back, historian Tim Gloege cried fowl at what he denounced as “evangelical gerrymandering,” at “respectable” evangelicals’ thinly-veiled attempt to define away their “embarrassing spiritual kin” by insisting they weren’t “real” evangelicals—something they had been doing for over a century.

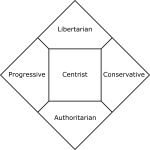

Debates over who is and isn’t an evangelical have become commonplace among scholars. Some of these debates have played out here at the Anxious Bench. Should evangelicalism be a theological category, à la David Bebbington? If so, people of color deserve a prominent place within evangelicalism. Or, is “evangelicalism” a cultural movement—one defined by its whiteness and its politics as much as (if not more than) by any particular statements of belief? Should we think of evangelicalism first and foremost as a global movement? As one represented by such luminaries as John Wesley, Jonathan Edwards, and William Wilberforce? Or as the politicized, white, God-and-country movement best represented by Robert Jeffress and the Duck Dynasty clan?

What if the answer is all of the above?

For scholars, perhaps the time has come to set aside our quibbling over definitive rubrics and our attempts to dictate, once and for all, who is and who is not an evangelical, and instead begin to consider evangelicalism as an imagined religious community.

There are, in fact, many evangelicalisms, and each is imagined with a different center and different boundaries.

If we consider “evangelicalism” an imagined religious community—imagined as inherently limited, bounded, with insiders and outsiders—we must pay close attention to questions of power. Individuals, communities, theologians, organizations, leaders, and distribution networks all imagine evangelicalism in different ways. (One person may even imagine it in conflicting ways simultaneously, using each for different rhetorical purposes, identifying with or against different imagined constructs.)

The primary question, then, isn’t which definition is “correct,” but rather which imaginings have more power to shape other people’s imaginings. When LifeWay decides you are no longer an evangelical, it matters. At least if you want to sell books. When the evangelical left claims the mantle of evangelicalism, it matters rhetorically. Does it matter beyond their own circles? Perhaps. This is a question worth exploring.

This shift in focus demands that scholars, too, examine their own positionality. How have scholars imagined evangelicalism, and to what end? How have their definitions opened up some questions and topics for exploration, and closed down others? Which scholarly imaginings have wielded power in the academy, and why?

All this is especially important to consider since so many scholars of evangelicalism have a personal connection to evangelicalism—either as evangelicals themselves, or as “exvangelicals.” Much of the scholarship on evangelicalism, in other words, has been generated by scholars who have a dog in the fight.

How has the fact that “Christian scholars” have largely (though not exclusively) told the story of evangelicalism shaped the story that has been told? Of course, there is no such thing as a generic “Christian scholar.” The fact is, much of the scholarship on evangelicalism has been produced by white, male, Christian scholars who are positioned near the centers of “establishment evangelicalism.” How has this shaped the definitions that have been proffered? How has power dictated which stories get told, and the shape these stories ultimately take?

Rather than seeking to impose one definition over all others, by conceptualizing evangelicalism as an imagined religious community we will be much more attentive to the ways in which evangelicalism is a dynamic, fluid movement, or series of movements, imagined and maintained through alliances, organizations, distribution networks, and cultures of consumption, each seeking to impose and enforce the boundaries of “evangelicalism” for varying purposes. And we will be forced to contend with how our own work as scholars is implicated in this imaginative process.