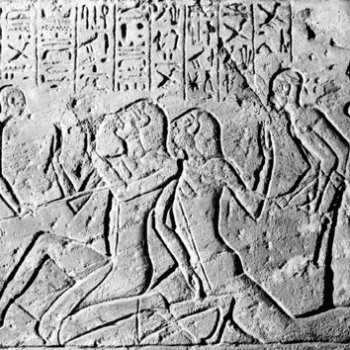

Some years ago, James Noyes published his book The Politics of Iconoclasm: Religion, Violence and the Culture of Image-Breaking in Christianity and Islam (2013). At the time, Islamist movements around the world were committing many notorious acts of destruction against historic monuments of other faiths, and it seemed quite shocking to draw any analogies with the Christian tradition. However, as I have learned all the more clearly doing my current work on the history of Byzantine iconoclasm, the two faiths are nothing like as radically different as many would like to think. Those parallels are especially close in the era of the Reformation.

Reviewing Noyes in the Times Literary Supplement, David Motadel wrote,

The prototype of all modern forms of iconoclasm [Noyes] found in Calvin’s Geneva and Ibn Abd al-Wahhab’s Mecca. Sixteenth-century Geneva witnessed one of the most devastating waves of religious image-breaking in history. Incited by a group of charismatic theologians – among them John Calvin himself – mobs raged against objects associated with miracles, magic and the supernatural, destroying some of the city’s most precious pieces of Christian art. Invoking the Second Commandment, they denounced these works as idols, and as remnants of a rural, feudal and superstitious world, a world corrupted by Satan.

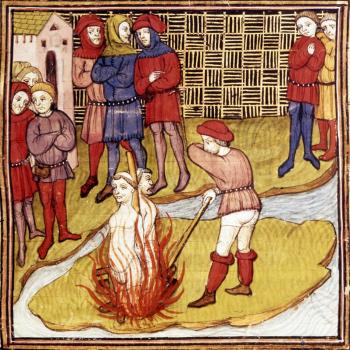

Nor was Geneva unusual. In Basel in 1529, widespread iconoclastic riots destroyed virtually all the material tokens of traditional Catholic worship and devotion in the cathedral and the city’s leading churches. To quote Wikipedia, “Significant iconoclastic riots took place in Basel (in 1529), Zurich (1523), Copenhagen (1530), Münster (1534), Geneva (1535), Augsburg (1537), Scotland (1559), Rouen (1560), and Saintes and La Rochelle (1562).” Even these manifestations were dwarfed by the devastating Storm of Images (Beeldenstorm) that swept over the Netherlands in 1566. I have now borrowed that Storm of Images phrase for my current book!

This movement was directed against any and all Catholic material symbols — against stained glass windows, statues of the Virgin and saints, holy medals and tokens. Such stories of image-breaking (iconoclasm) are familiar enough to anyone who knows about the Reformation, and there are plenty of scholarly studies. Recent works, though, emphasize that Iconoclasm was central to the Reformation experience, not marginal, and not just a regrettable extravagance.

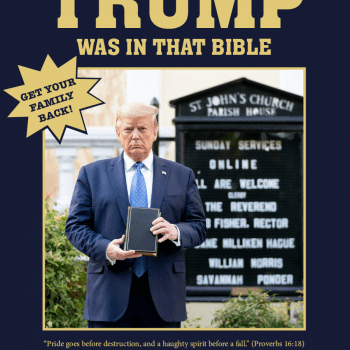

Historians of the Reformation tend to be bookish people interested in texts, so they focus on aspects of literacy and translation, with the spread of the vernacular Bible as the centerpiece of the story. The idea of the Reformation as a “media revolution” is common enough. Yes, we do read of outbreaks of destructive violence and iconoclasm, but these are usually presented as marginal excesses, or understandable instances of popular fury against church abuses. Once we get those unfortunate riots out of the way, we can get back to the main story of tracing the process of Bible translation. That’s very misleading. For anyone living at the time, including educated elites, the iconoclasm was not just an incidental breakdown of law and order, it was the core of the whole movement, the necessary other side of the coin to the growth of literacy. Those visual and symbolic representations of the Christian story had to decrease, in order for the world of the published Bible to increase.

In terms of the lived experience of people at the time, the image-breaking is the key component of the Reformation. In the rioting and mayhem, a millennium-old religious order was visibly and comprehensively smashed.

In words adapted from the Vulgate version of Job, the Calvinist motto proclaimed, Post Tenebras Lux: After darkness, Light. (And that is still Geneva’s motto). I make no apology for citing the Quranic verse that early Muslims used to justify their own acts of iconoclasm: “Truth has come and falsehood has vanished.” That is actually not too far from Calvin’s sentiments.

We also need to think through the effects of such violence. Protestant historians sometimes write as if the Reformation brought religious knowledge and spirituality to a Continent from which it had been largely lacking. Of course, pre-Reformation believers had ample access to the Christian tradition, but usually mediated through non-literate forms, through drama and visual culture. When Reformation states and mobs destroyed or suppressed those alternative cultural forms, they were in effect removing popular access to the understanding of faith and the Christian story. It was also an unabashedly top-down phenomenon. That image-breaking we hear about was invariably the work of urban mobs, in societies that were overwhelmingly rural. The Reformation was a war of the cities against the countryside, of the ten percent (perhaps) against the ninety percent.

It would be decades or centuries before the new religious order based on books and literacy would disseminate throughout the whole country, including rural areas. Urban communities spent those decades sneering at the religious ignorance of the peasants.

From the perspective of visual art and culture, the Reformation was one of the greatest catastrophes that ever befell Europe. It also had a massive class bias, in that it targeted objects beloved by ordinary people, while princes and dukes were able to safeguard their Classical treasures. Obviously, there were also cultural gains, in the form of mass literacy, and new forms of visual media, including pamphlets and cartoons. But in terms of paintings, murals, sculpture, textiles, architecture, and stained glass, the losses were irreparable.

Centuries of vernacular culture and piety vanished within a generation.

Analogies between the European Reformation and contemporary Islamism are much closer than many Protestants would like to admit. In 1566, the Ottoman sultan Suleiman sent a fan letter to the Dutch Protestants who were so profitably engaged in smashing all those “idols,” and offered an alliance.

James Noyes compared Calvin closely to Ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703-92), the founder of the Wahhabi movement that has so often featured, unflatteringly, in our headlines over the past two decades. Like Calvinism, Wahhabi Islam urged the destruction of everything that could be seen as a later accretion to the core of the religion, as well as all manifestations of paganism or idolatry. Since the 1920s, this version of the faith has been the official creed of Saudi Arabia, and variants of it are found among Islam’s violent and extreme movements. It is the Wahhabi tradition that has unleashed or justified the savage destruction of shrines and holy places that has been so widely deplored in the past half-century or so. This includes the Taliban’s destruction of the Buddhas in Afghanistan, the attempted eradication of the glorious shrines and libraries of Timbuktu, and the annihilation of most of the ancient (Islamic) shrines and tombs around Mecca itself.

Modern Westerners are rightly appalled by such acts as desecrations of humanity’s cultural heritage. But such outrage demonstrates a near-total lack of awareness of the West’s own history. Nothing that the Islamists have done in this regard would cause the sixteenth century Protestant Reformers to lose a moment’s sleep. They would probably have asked to borrow hammers and axes so they could join in.

In comparing the Protestant Reformers with contemporary Wahhabis, I am not commenting on their theology, their attitude to violence, or to social issues like the status of women. I am speaking very specifically about attitudes to images in religious devotion, and the absolute supremacy of the written text, with the physical iconoclasm that followed from those positions.

During all the commemorations of the Reformation in and around 2017, I was struck, but not surprised, by the near-total lack of reference to the central role played by iconoclasm. It was at the heart of the message.