A couple of recent encounters have reshaped my understandings of the ancient world, and specifically of Christian origins. The specific topic is Roman roads. Like everyone, I have always known that the Romans built such things, but these discoveries have really helped me grasp their importance as never before, and I am still processing the implications. In a couple of ways, Roman roads are suddenly back in the news.

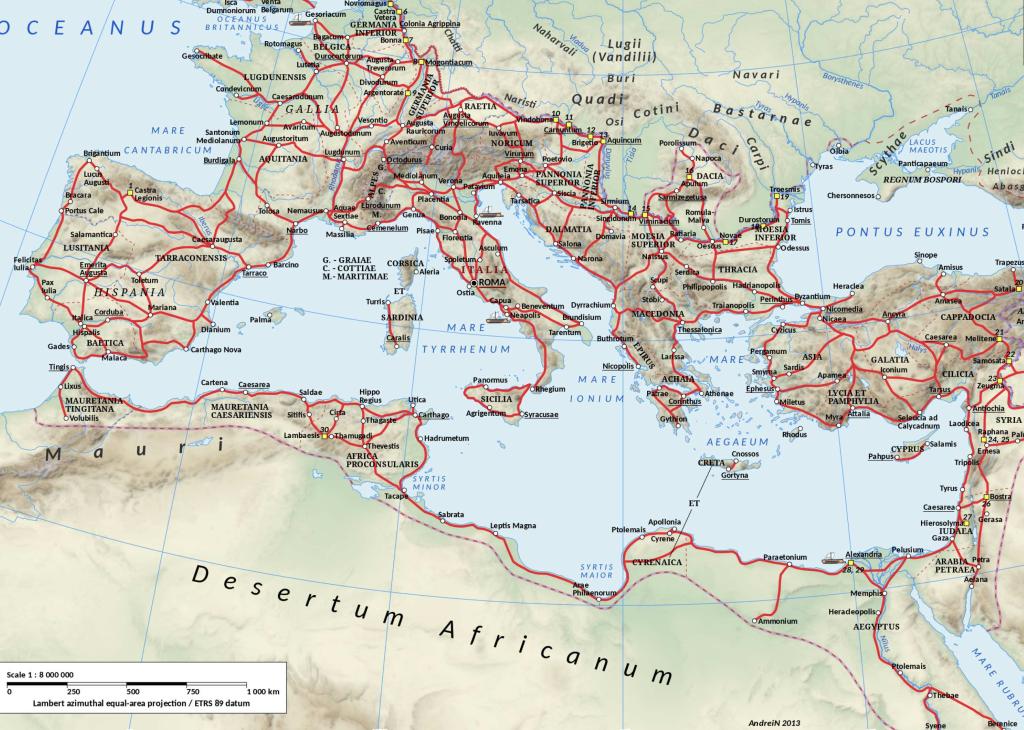

The first is an excellent series of radio programs or podcasts by the British archaeologist Bettany Hughes, who is a major media personality in the UK. She has a series of three episodes about the splendid Roman road called the Via Egnatia, which ran for six hundred miles from Byzantium (later Constantinople) to Dyrrachium/Durrës on the Adriatic, passing through such key New Testament sites as Philippi and Thessaloniki. Knowing the Via Egnatia is critical to understanding just what Paul and the early Christians were doing, and how the new religion spread. It would be possible to write a history of that particular road alone in term of the religious and mystical ideas that it conveyed, from the early Jesus Movement to the Christian heresies of the high Middle Ages, and later Sufi orders. The road remained a principal artery for imperial communications well into the Byzantine era, and indeed through Ottoman times. The programs are available on BBC Sounds, and they are great listening

That is very good in its own right, but more generally useful, indeed startling, is a remarkable map devised by Sasha Trubetskoy, which I can’t reproduce here for copyright reasons, but you can find it easily enough. What Trubetskoy has done is simple but brilliant. He has mapped the empire’s Roman roads in a stylized form imitating a modern subway map, all of which ultimately derive from the original designed for the London Underground. As with subways, you don’t need to understand every twist and turn of the route, which you can depict as a straight line, with cities as “stations,” some of which are junctions and points at which to change lines. To understand just what a contribution this is, contrast any of the many standard maps we get of those road systems, which often seem so puzzling and intricate.

The “subway” map is very effective indeed: just look at it, and think about the implications for early Christianity, which was centered on the five great cities of Rome, Carthage, Alexandria, Antioch, and Ephesus. Each of these hubs stood at the center of a far-reaching network of fine roads, which our map allows us to see with ease. Just to take a prominent example, one great Asian road stretched from Jerusalem to Tyre and Antioch, on to Smyrna and Ephesus, and then connecting to the Via Egnatia for access to Europe.

You can gaze at this map for hours and see connections and insights. So Saul of Tarsus came from “no mean city”? Look at Tarsus, and where it stands as a junction between that Asian road and the Via Valeria crossing Asia Minor, through Tyana and Ancyra. Not mean at all. Look how the Via Graeca runs from Thessaloniki to Corinth. Or see how those roads are so crucial for the world of the seven churches named in the Book of Revelation.

In Gaul, look at Lyon/Lugdunum, which was such a key center for second century Christianity in those parts, and just look at the road networks and communications that are so essential to that role. The city is actually a junction for three key roads. The mission routes, and the subsequent history, write themselves.

Obviously too, everything I am saying here is essential for understanding the spread of the Jewish Diaspora in these same centuries.

It would be nice to have the sea routes included as well, especially for the world of Acts. I don’t claim this as a scientifically valid survey, but I see that the word “sail” features fifty times in the whole NIV version of the Bible, and Acts alone counts for 29 of those usages. Luke was very well aware of how his characters got around, of how sea and roads worked together, and you can actually do a good reconstruction job of the routes they traveled.

Anyway, I will take what I can get by way of resources. In summary, just look at the “subway” map, and see for yourself.

Finally, I note a scholarly article that just appeared, which has a lot of implications for all sorts of fields, again including the history of religion. This is Carl-Johan Dalgaard, et al, “Roman Roads To Prosperity: Persistence And Non-Persistence Of Public Infrastructure,” Journal of Comparative Economics 50(4)(2022): 896-916. Briefly, the article suggests very strong continuity between the way Roman roads were distributed at the height of the Roman empire and later patterns of prosperity and commerce. Partly, that means that those roads were very well sited and built, which we already knew, but it also suggests that the fact of having those roads had an amazingly potent and long-lasting influence on later societies. “Ancient Roman roads predict modern roads’ location and local economic activity.” The key factor making for such continuity was the market towns that grew on the strength of those old and deeply familiar routes.

As the authors say,

We examine the territory under dominion of the Roman Empire at the zenith of its geographical extension (117 CE), and find a remarkable pattern of persistence showing that greater Roman road density goes along with (a) greater modern road density, (b) greater settlement formation in 500 CE, and (c) greater economic activity in 2010–2020.

The linkage was not perfect:

Exploiting a natural experiment, we find that persistence in road density and the strong link between early road density and contemporary economic development weaken to the point of insignificance in areas where the use of wheeled vehicles was abandoned and caravan trade routes replaced road-based trade from the first millennium CE until the late modern period. Studying channels of persistence, we identify the emergence of market towns during the early medieval period and the modern era as a robust mechanism sustaining the persistent effects of the Roman roads network.

Interesting and important stuff, and especially for Christian history, a topic the authors do not really get into. Those market towns would often have become bishoprics, and centers of ecclesiastical life and organization.