I have been posting about the linkage between empires and the shaping of world religions, particularly (by no means exclusively) Christianity. I have especially stressed the role of unintended consequences, of empires doing things that resulted in outcomes utterly different from what they wanted or expected. Man proposes, and God disposes.

When we write Christian history, one empire in particular often escapes our attention, and it provides a vast hole in the story. Once upon a time, in the ancient world, there was a vast empire. Although it was at times deeply hostile to Christians, which it actively sought to suppress or exterminate, the fact of that empire’s existence provided an essential framework for Christian expansion. Christian communities flourished in the empire’s booming cities, which they made the seats of church organization. They also benefited from the stability and peace that the empire imposed, and the vast network of roads and sea communications that it sustained, not to mention its common languages. Where the empire stretched, there followed the churches. Ultimately, the empire faded and died, but the churches that had formed in that matrix survived and flourished, outlasting the empire for many centuries.

Such a phenomenon is of course very familiar in the Western world, which emerged on the ruins of the Roman Empire. But in this instance, I am not speaking of the Roman Empire, but of the vast eastern superpower that was its counterpart and deadly rival: the Sassanid realm of Greater Persia. Without that other empire – that empire in the mirror – the story of Christian expansion to the east, as well as the west, is incomprehensible.

Although the Sassanid Empire attracts plenty of fine scholars, it is much more difficult to find general histories of that state than the Roman Empire. Yet its achievements were deeply impressive. The dynasty lasted from 224 to 651, and stretched far beyond what we think of today as Iran, and deep into Central Asia. That was so critical because the Sassanids linked directly to the Silk Route, the world’s most important commercial artery at that time, and a crucial cultural channel, stretching from Syria to China. The Sassanid capital of Seleucia-Ctesiphon on the Tigris was in its day one of the world’s greatest cities, and the direct precursor of later Baghdad.

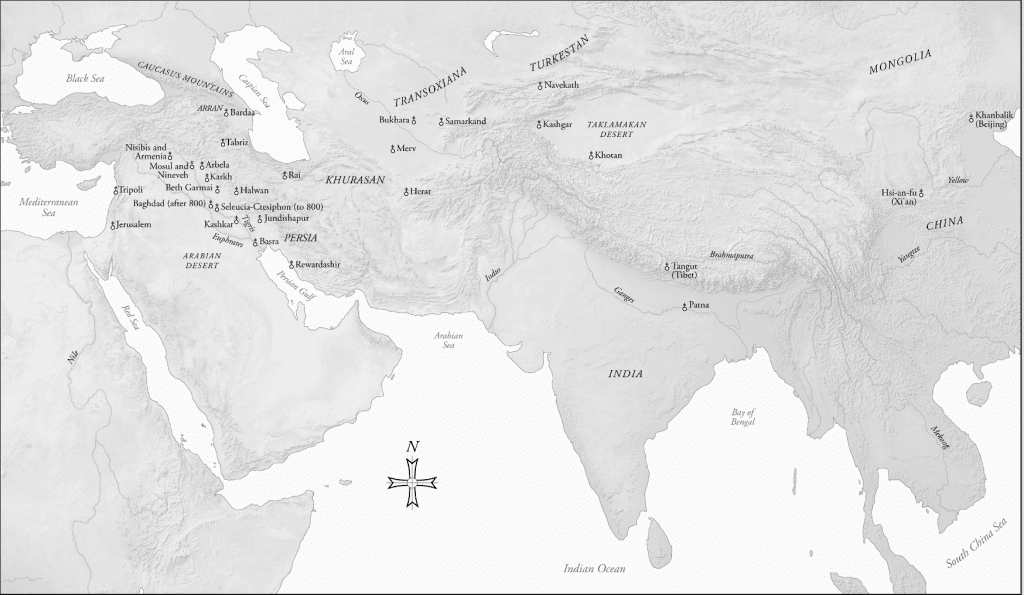

The story of Christianity in the East depends utterly on Sassanid affairs. Yes, anti-Christian persecutions could be savage, under a realm that strictly followed the Zoroastrian faith. But Christians also used the imperial framework to expand into Central Asia, through what we now call Afghanistan and the “stans” of Central Asia, and into the Silk Route itself. Just look for instance at a map of the metropolitan sees of the vast Church of the East, the so-called Nestorians. Is that not a ghost of the Sassanid world?

Just how did all this happen? Christianity made its first impact in the distant western regions of what was then the Parthian Empire, in regions that today we place in northern Iraq or eastern Turkey. (I describe the geographical background at length here). By the second century AD, the faith was well established in these borderlands between the two empires, in kingdoms like Osrhoene (with its capital at Edessa), and Adiabene (Arbela). It later gained a critical foothold in the Caucasus, in Armenia and Iberia. Sometimes Rome ruled all these lands, sometimes Persia prevailed, but most commonly, the empires shared the lands between them, while tolerating a network of buffer states.

Just how Christianity spread much further afield in the east is a classic story of unintended consequences. At least at first, many, perhaps most, of the Christians who found themselves under Persian rule really had no wish whatever to be there.

As I remarked, major Christian growth first occurred on the Empire’s western borderlands, which divided the Persian and Roman realms. Wars and conflicts that raged over these regions from the first century through the sixth, and they became still more fierce under the Sassanid empire. War meant enslavement, deportation and population movement, which brought reluctant populations into new lands. Here, though, they introduced new faiths, often to the horror of their new masters.

Christian slaves played a potent role in spreading the faith into Caucasian lands like Iberia and Georgia. Later, borderlands adopted particular forms of faith to appeal to one superpower, and to seek help against its rival. Once war broke out, it was usually fought in the same general areas, where Christianity was both very strong, and exceedingly diverse. In modern terms, this meant northern Iraq, eastern Syria, and especially eastern Turkey, with the Christian holy city of Nisibis a pivotal prize.

The better the Persians did in war, the more territories and populations they gained in these disputed areas, and the greater the unwanted spread of Christianity into their own empire. If they gained a substantial Christian minority, they had only themselves to blame. It was not so much that Christianity came to the Persian Empire: the Empire came to them.

The main “culprit” for Christian expansion was king Shapur I, son of the founder of the Sassanid dynasty, Ardashir. Shapur’s wars against the Romans raged through the 240s and 250s, culminating in his spectacular capture of the Roman Emperor Valerian. Briefly, Shapur even occupied Antioch itself. He conquered and deported many peoples, bringing them home to Persian soil.

One of the settlements he created would become very influential indeed. In the 260s, Shapur settled here many Roman prisoners he had taken during his successful war. A city emerged, bearing his name: Gundeshapur (Jundaisapur). In the fifth and sixth centuries, this emerged as one of the greatest intellectual centers of the ancient world, almost a facsimile of a research university, with a special focus on medicine. Although it is difficult to disentangle truth from legend, Gundeshapur is often cited as a major influence on early Islamic learning and scholarship. And it was, par excellence, a Christian center, base of one of the metropolitan provinces of the Church of the East. Its Christian identity became even more marked when it became a refuge for scholars fleeing religious oppression in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Not surprisingly, then, by the late third century, the Persian Empire found itself with abundant Christians, drawn from a wide variety of theological and ethnic traditions. Over time, the Church of the East operated ever more closely with the Empire, despite its apparently hostile religious traditions. I quote the Encyclopedia Iranica:

In 410, a Synod was convened at Ctesiphon: The royal capital had become also the acknowledged center of Christianity in the Empire. The proceedings began with a prayer for the king, Yazdegerd I; and the Synod adopted the creed of Nicaea. Six provinces were then listed as Christian jurisdictions, including Ray and Abaršahr; in the late 6th century, Marv and Herat, whose Christian communities were already centuries old, are prominently mentioned.

By the seventh century, the Church of the East happily allied with the Sassanids against the Orthodox Christians of Constantinople. At times, it looked uncannily like an imperial state church.

In the West, the papacy maintained its center at Rome long after the passing of the Empire that had originally stood at that place. In the East, the Church of the East occupied the Persian imperial city of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, and stayed there long after the Arab Muslims had supplanted the Persian empire. Only when the Muslim Caliphate moved to nearby Baghdad did the Church’s Patriarch follow the new rulers, and select a new residence. Meanwhile, Christian missions were enthusiastically spreading north and east into Central Asia, through what had been the provinces of the Sassanid empire. And thus was the Church of the East born.

As I’ll suggest next time, if Sassanid Persia never became a Christian empire, the dynasty’s Christian connections were very powerful indeed. Empires are strange things… See what happens when you go and conquer and deport all those innocent people, and bring them back with you?

SOURCES

Michael R. Jackson Bonner, ed., The Last Empire of Iran (Gorgias Press 2020), especially pages 313-348.

Jes Peter Asmussen, “Christians in Iran,” in Ehsan Yarshater, ed., The Cambridge History of Iran Volume 3: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanid Periods, Part 2 (Cambridge University Press, 1983), 924-48.

R.N.Frye, “The Political History Of Iran Under The Sasanians,” in Ehsan Yarshater, ed., The Cambridge History of Iran Volume 3: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanid Periods, Part 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1983), 116-180.

Richard E. Payne, A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity (University of California Press, 2015)

Parvaneh Pourshariati, Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran (I. B. Tauris, 2008).

Eberhard W. Sauer, ed., Sasanian Persia: Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia (Edinburgh University Press, 2017).