Let’s look closer at the details of the Garden of Eden story (part 1 is here). As history—or even a coherent story—it doesn’t stand up.

Let’s look closer at the details of the Garden of Eden story (part 1 is here). As history—or even a coherent story—it doesn’t stand up.

- Omniscient God isn’t very knowledgeable when he goes into the Garden and doesn’t know where Adam and Eve are (Gen. 3:9). Omnibenevolent God isn’t very benevolent when it comes to delivering their punishment. This is another parallel with the Atra-Hasis epic—those gods didn’t know everything and weren’t always benevolent either. As one commenter noted, “God’s powers can’t be that amazing if you can get them from a fruit tree.”

- As crimes go, this one was a misdemeanor. Admittedly, God did say to not do something and they did it, but how about just a scolding? This was the first bad act in their lives. Isn’t the trans-generational punishment out of proportion to the crime?

- Before Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, they didn’t know good and evil. Why blame them for doing something wrong when they couldn’t know it was wrong? It’s like punishing a two-year old for a moral infraction. In fact, Adam and Eve might not even have been two years old themselves.

- If Man understands good and evil today (we possess the knowledge of the Tree), why are we so bad at figuring out good and evil? Okay, let’s assume that selfishness and other base desires muddy the waters. Let’s assume that someone could know the right course of action but choose the easy or pleasurable over the right. Shouldn’t we all at least agree on what’s good? How could post-apple humans be divided on abortion, gay marriage, euthanasia, and capital punishment?

- Getting wisdom is a bad thing? The Bible makes clear that it’s not: “How much better to get wisdom than gold, to get insight rather than silver!” (Prov. 16:16).

- Could an omniscient God have been surprised at the result of the Garden of Eden experiment? And if he knew the outcome, why go through the charade? (Or might this all just be mythology … ?)

- Tertullian said of women, “You are the devil’s gateway; you are the unsealer of that (forbidden) tree; you are the first deserter of the divine law.” But read the story—Adam was with her the whole time. Why give Eve extra blame?

- Why are their descendants cursed for all time—women with labor pain and men with difficult toil—when the descendants didn’t do anything? We see the same thinking in the second commandment (“I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me”), which probably also came from the J source. It’s nice that things lighten up in later centuries (see Deut. 24:16 or Jer. 31:30), though this doesn’t put God’s unchanging moral law in a good light.

At this point in the Bible, Jesus wasn’t even a twinkle in God’s eye, but it is worth noting that while Jesus provides forgiveness of one’s sins, Christians are still punished for Eve’s sin.

- This is an aside, but it is curious that Christian Creationists who object to humans evolving from bacteria have no problem with God making Adam from dust (Gen. 2:7). Indeed, the word Adam comes from the Hebrew adamah (dust).

- The NET Bible comment on Gen. 2:17 (“for when you eat from [the Tree,] you will surely die”) makes clear that this phrase means that death will happen almost immediately, as if the fruit were coated with cyanide. But, of course, the serpent was right, and they don’t die. Indeed, Adam dies at 930 years of age.

Apologists respond that this instead means that they will die eventually, that this introduced physical death and they would no longer be immortal. But the text makes clear that they never were immortal. They were driven from the Garden so they wouldn’t eat from the Tree of Life. That’s what makes you immortal.

Apologists try again: they say that “die” meant spiritual death. First off, that’s not what the text says. Second, the animals were driven from the Garden as well, so there’s no reason to imagine that their death was any different than Man’s. If the animals’ death was physical and not spiritual, what’s to argue that Man’s is any different?

- Christian theologians tell us that the serpent was Satan in disguise, but (yet again) that’s not what the text tells us. It was a serpent, not Satan, and that’s what Jews today will tell you. And why is the serpent the bad guy? He told the truth! He was a Jewish Prometheus.

I’ll close with comments from Ricky Gervais, who imagined the snake having this to say in response to God’s punishment that he crawl on his belly for the rest of his life.

“But I already.… Oh no! Oh yeah, you’ve done me, yeah. No, we’re even now. I asked for that. Okay, cheers. Oh—how does this work again? Owww—I’m being punished. This is rubbish—I wish I could fly, like normal.”

And the Son of God died;

it is by all means to be believed, because it is absurd.

And He was buried, and rose again;

the fact is certain, because it is impossible.

— Tertullian

Photo credit: Paul Hocksenar

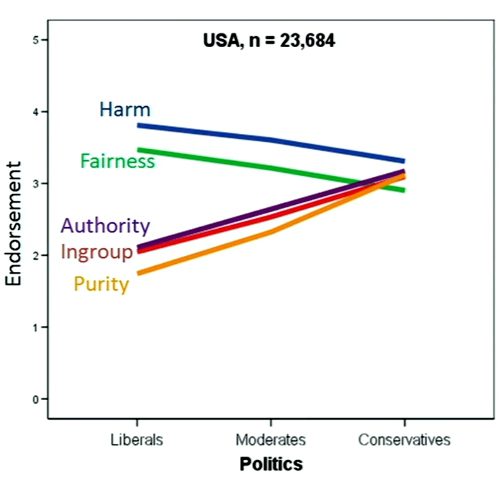

Why do liberals and conservatives argue so much about morality? Don’t they have a common sense of right and wrong?

Why do liberals and conservatives argue so much about morality? Don’t they have a common sense of right and wrong? As Haidt’s drawing shows, Americans across the political spectrum strongly endorse the foundations of Care/Harm and Fairness. Not so for the next three. The conservative says “go team,” while the liberal says “celebrate diversity” (#3). The conservative says, “respect authority,” while the liberal says, “question authority” (#4). The conservative says, “life is sacred,” while the liberal says, “keep your laws off my body” (#5).

As Haidt’s drawing shows, Americans across the political spectrum strongly endorse the foundations of Care/Harm and Fairness. Not so for the next three. The conservative says “go team,” while the liberal says “celebrate diversity” (#3). The conservative says, “respect authority,” while the liberal says, “question authority” (#4). The conservative says, “life is sacred,” while the liberal says, “keep your laws off my body” (#5).

C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity is a fundamental work in Christian apologetics. Many Christians point to this book as a turning point in their coming to faith. I’d like to respond to some of Lewis’s ideas.

C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity is a fundamental work in Christian apologetics. Many Christians point to this book as a turning point in their coming to faith. I’d like to respond to some of Lewis’s ideas.

A century ago, America was immersed in social change. Some of the issues in the headlines during this period were women’s suffrage, the treatment of immigrants, prison and asylum reform, temperance and prohibition, racial inequality, child labor and compulsory elementary school education, women’s education and protection of women from workplace exploitation, equal pay for equal work, communism and utopian societies, unions and the labor movement, and pure food laws.

A century ago, America was immersed in social change. Some of the issues in the headlines during this period were women’s suffrage, the treatment of immigrants, prison and asylum reform, temperance and prohibition, racial inequality, child labor and compulsory elementary school education, women’s education and protection of women from workplace exploitation, equal pay for equal work, communism and utopian societies, unions and the labor movement, and pure food laws.