(11-27-12)

***

The following all came about in the combox for Brandon Vogt’s excellent article, “How Cardinal Newman Handled the Haters” (11-26-12). A fellow Catholic writer, Paul Priest, made some very critical observations about Newman’s famous sarcastic retorts to the charges of fundamental dishonesty leveled at him by the Anglican priest and polemicist, Charles Kingsley. Brandon himself asked me my thoughts in response, and I gave them, complete with several Newman quotations, culled from my research for my Quotable Newman and it’s eventual follow-up volume. Paul replied again, and I counter-replied. It has been a very enjoyable exchange. Paul’s words will be in blue.

Newman’s conflict with Charles Kingsley is one of the two historical examples I bring up when I hear the very common and erroneous opinion that one must always turn the other cheek. Not true. It’s not an absolute. The other example is St. Paul’s Socrates-like defense (“apologia”) of himself in the Roman / Jewish courts against untrue accusations (see the latter half of the book of Acts). He even appealed to his Roman citizenship (which eventually saved him from being crucified, like St. Peter). That’s hardly turning the other cheek.

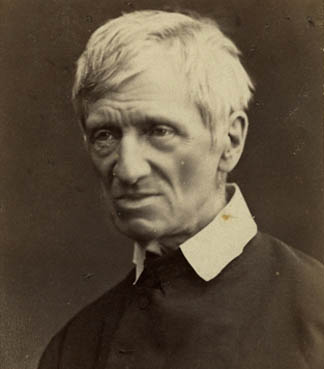

But Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman defended himself with class and as much charity as could be mustered towards a vile, utterly groundless and irrational, scurrilous personal attack. He had heard it for at least 19 years up to that time (since his conversion), and was totally fed up with it. I know something about the whole process, because I recently compiled a volume of his quotations and read most of his books and many of his letters. He had agonized for years over the lies being spread about him (as any normal human being would have).

The result of his extended counter-reply was that he literally won over the affections of the English people, and this had truly momentous consequences in terms of an acceptance of Catholicism in a country with a record of bitter (and often hateful) anti-Catholicism for the previous 300 years. When high-profile Catholics are attacked, it is never solely about them. It’s about the Church: that is always the target: at least in Satan’s strategy that ultimately lies behind all lies, and particularly those against Holy Mother Church and her leaders.

* * *

Sorry Brandon but you’re missing the Victorian English barbs within Bl. JHN’s missive. It spews fury, venom, contempt and condescension via enthymemes and that which is left defiantly unsaid; there is even disdain at the worth of Rev. Kingsley himself; not merely what he wrote.

The use of ‘gentlemen’ is perjorative [i.e. if you were gentlemen you should never have allowed such a comment to be published – so you’d better start acting like gentlemen now!]

The trolls are most definitely being fed – Mr Kingsley is being attacked with vituperation and accused of being an unworthy slanderer and the publisher/editor is being accused of being either gullibly reckless or even complicit with Rev Kingsley’s sentiments.

The ‘politeness’ inferred by a modern reader is very far from complimentary – rather the reverse. JHN hasn’t assumed the best either – rather than it being taken for what it was – as a mocking side-swipe at the ‘Jesuitical’ approach that virtually every Anglican would use as a weapon against a Papist; rather JHN decides to take the term literally and outside of its context – you might not notice it but JHN’s also launching a vicious left-hook at the editors/publishers that their ungentlemanly conduct demands restitution lest they be found guilty by association. The ad hominems in his letter swoop in for the attack like valkyries.

I’m really sorry to rain on your parade, but seriously: Your first proposed ‘contemporary blog-like’ response with its tirade of well-worn insults is actually significantly less ascerbic, vitriolic and ‘below the belt’ than the one Blessed John Henry Newman wrote himself.

It’s a different culture in a different era but everyone reading JHN’s letter would wince – but the letter is redolent of Aneurin Bevan’s comment on Prime Minister Anthony Eden “If the Prime Minister is sincere, and he very well may be; then he is too stupid to be Prime Minister”.

No-one from a spanish background would denounce anyone as a thief even if they knew they were…it would be too socio-culturally demeaning for all involved; instead they would confront the criminal with “I appear to have mislaid my wallet” [which is a euphemism for I know you’ve taken it – give it back or I’ll break you neck!]

Quentin Crisp said of the British “The Americans always say “Oh the British are so polite” without realising that the British are only ever polite to people they can’t stand!” If the British like someone a conversation will be filled with cordial familiarity and jovial put-downs, cynicisms and sarcasms.

Heart may speak unto heart – but there was certainly not an ounce of cordiality in that letter – to those who understand the tone I think the response would be a cringing shock.

. . . you’re being dazzled by the halo and the assumption that words can be interpreted at face value without the locale, the era or the cultural argot and the terminologies utilised being taken into consideration. They can’t.

You’re presuming this is the height of politeness, courtesy, civility and decorum with neither a raised word nor any imputation on another’s reputation; when it reality this is a withering character assassination and the remarks of someone who is incandescently livid and casts insults accordingly!

Take a look at what he REALLY says about Charles Kingsley [and the editor]

“I neither complain of them for their act, nor should I thank them if they reversed it.”

That’s Victorianese for “I don’t give a [expletive deletive] what they do – they’re not worth it – those [expletive deleted] can go [expletive deleted] themselves for all I care. I expect nothing less from [derogatory term] like that of [derogatory term] intellect and [derogatory term] morality – and as for a retraction or an apology it would be of as much worth and contain as much false authenticity and sincerity as the [expletive deleted] they’ve already written/allowed to be written”

..how’s that for an ad hominem?

..this is confirmed by the accusation that they didn’t merely commit grave slander but ‘gratuitous’ slander too.

[thinking the best of them?]

…and the word ‘gentlemen’ [especially in the sign off] is used as a provocative confrontational bludgeon that they are not being deemed gentlemen or considered gentlemen because the evidence suggests they have not acted like gentlemen and should bloody well start to act like gentlemen – if that’s at all possible…

[that can hardly be considered any of the three aspects of your advice]

…he even twists the knife by saying that he doesn’t and would never normally read the publication – the only reason he’s responding is because he was notified…

With the English you have to notice the extraneous, the peripheral and the nuances – hardly anything ever means what it says and a word is hardly ever wasted – if it’s there – it’s there for a purpose and usually has a big motive pushing it – you just need to find it…

We rarely write, say or do anything which isn’t contaminated with a[n] [un]healthy dose of irony or sarcasm. Newman was an exemplar of it.

I doubt if anyone had more ideological adversaries in the world than GKC – but is there one among them who didn’t adore him? Even when he’d slain their heretical dragons and exorcised their fallacious phantoms and was the field marshal of the army whose unending onslaught ravaged everything in which they lived and believed? To Bernard Shaw and HG Wells when GKC died the moon was twice as lonely and the stars were half as bright – they loved him like a brother. Why? Because Gilbert spent his whole life arguing – so much so that he had no time for quarrelling…

Now if we are to love and honour Blessed John Henry Newman for who he was – we have to stop rewriting who he was – he was no plaster saint – no saint ever was..they all [bar one] had their flaws…they had feet of clay because they were picked out of the mud where they were walking…and with Newman it was getting upset over minor slights and actuating generations-long pig-headed recalcitrant feuds over the most ridiculous issues…

He may have been good, kind, holy, overflowing in intellect and wisdom..and although he’s very precious to us now – when he was alive he was ‘precious’ in the wrong way.

He quarrelled, he took offence, he exacted canly, he sent people to Coventry for decades and had no qualms garnering support against the object of his disdain and antipathy so it might turn into a farcical internecine conflict continuing even after he was long dead…he might have been worthily childlike in so many ways but in one way he was childish..he was very sensitive and got hurt very easily…and was hyperbolic in his distress when he did get hurt..which was probably a path to his salvation…by that wound and its healing maybe Christ was able to enter into his life in ways unimaginable if he hadn’t had that sensitive side? Maybe the prayers and hymns and writings and poems wouldn’t have a tenth of their beauty and understanding if he hadn’t borne that cross?

Anyone who has read the Apologia may sympathise with him and his emotional and civic and intellectual struggles – but even the most warm-hearted of us must concede that there are times the blessed future cardinal was a bit of a narcissistic jessie fretting over non-existent anxieties and self-imposed unnecessary imaginary burdens – and despite being really brave there were times when the best thing for him would to have had a father figure giving him a good shake, or throwing a big bucket of ice-water over him or a good kick in the seat of the pants…

…and a mother figure to force him and his opponent to say sorry and shake hands like nice young gentlemen and make up.

Love Blessed John Henry Newman – but please don’t forget that he had his ‘Sheldon Cooper’ side to him too..we can love and forgive and be willing to excuse at any available opportunity..but to deny it is to turn him into marble..and he’s not!

[all bolded emphases added]

* * *

I think his take is sheer nonsense: armchair psychobabble and reading into completely justified, brilliant satirical barbs (things that Jesus and Paul both did; therefore they are not at all intrinsically sinful in every instance), all kinds of nefarious motives that are not there. It’s assuming the worst of someone rather than the best: which the Christian must not do (1 Corinthians 13).

I think Newman was doing a lot of what I often do, myself: taking an opportunity of a topic immediately at hand to launch off into observations about the larger related issue (in this case, a profound cultural anti-Catholicism).

His book Lectures on the Present Position of Catholics in England (1851) contains some of the most delightful sarcasm I have read, anywhere. And it is good not only because it is spot-on and matchless prose (as always with him), but precisely because the subject matter offered such treasure-troves of folly and silliness to draw from.

Likewise, with Kingsley. Newman knew full well what was behind the attack: it was directed against Catholicism in the usual garden-variety way, with allusions to jesuitical casuisty, etc: every timeworn stereotype in the book. And so he was simultaneously dealing with that. We know that, from what he wrote about the exchange. It was an opportunity to slay the beast of cultural anti-Catholicism, using the vehicle of a ridiculous personal attack, handed to him on a silver platter. So, e.g., he wrote in a letter, while putting the Apologia pro vita Sua together:

So far as my character is connected with the fact of my conversion I have wished to do a service to Catholicism, . . . (Letter to Frederick Rogers, 1 May 1864)

Any true contempt was towards the incessant lying and revisionism of English anti-Catholicism: not towards Kingsley per se. He was just a pawn in that larger game. Hence Newman wrote eleven years later:

The death of Mr Kingsley, so premature, shocked me. I never from the first have felt any anger towards him. As I said in the first pages of my Apologia, it is very difficult to be angry with a man one has never seen. A casual reader would think my language denoted anger – but it did not. . . . much less could I feel any resentment against him when he was accidentally the instrument in the good Providence of God, by whom I had an opportunity given me, which otherwise I should not have had of vindicating my character and conduct in my Apologia. (Letter to Sir William Henry Cope, 13 February 1875)

Now, we can take Cardinal Newman’s own report of his interior feelings at face value, or we can rashly speculate and attribute ill will. I try to extend good will to any man. In this case, we have a saintly and rather extraordinary man: all the more reason to accept his own report. Justified sarcasm does not prove ill will or personal derision and detestation.

We also know from his account of writing the Apologia that this was a very unpleasant task for him indeed: a state of mind quite contrary to the imaginary fiction that our friend has dreamt up:

In writing I kept bursting into tears—and, as I read it to St. John, I could not get on from beginning to end. (Letter to William John Copeland, 19 April 1864)

. . . the most trying work which I ever had to do for nothing. During the writing and reading of my Part 3, I could not get on from beginning to end for crying . . . (Letter to Frederick Rogers, 22 April 1864)

It has been a great misery to me. (Letter to R. W. Church, 26 April 1864)

I have never been in such stress of brain and such pain of heart, and I have both trials together. Say some good prayers for me. . . . I have been constantly in tears, and constantly crying out in distress. . . . And then the third great trial and anxiety, lest I should not say well what is so important to say. (Letter to James Robert Hope-Scott, 2 May 1864)

. . . I have done a book of 562 pages, all at a heat; but with so much suffering, such profuse crying, . . . (Letter to Sister Mary Gabriel du Boulay, 25 June 1864)

I never had such a time, and once or twice thought I was breaking down. (Letter to Mother Imelda Poole, 25 June 1864)

None of these letters, by the way, are in my current book, The Quotable Newman. It had to be edited down . . . They will be in a Vol. II eventually, filed under a section devoted to his own thoughts about the Apologia.

One line in Paul’s observations is very telltale, I think: “with Newman it was getting upset over minor slights and actuating generations-long pig-headed recalcitrant feuds over the most ridiculous issues…”

That was surely the case at times for Newman, as with any sensitive or thoughtful person who loves God and others. But it is not the case in the dispute with Kingsley. Far from being a “minor” thing or “ridiculous” it was of the highest importance in the history of Catholicism in England and the world (Newman being perhaps the most notable and brilliant convert since St. Augustine).

The subsequent favorable reaction of England proves this as no amount of analysis from anyone could. It was God’s providence for it to happen. Newman, being very spiritually attuned and discerning, thankfully knew that and endured the misery that he did, in defending himself (and really, the Church) against scurrilous lies.

Lastly, as to the juxtaposition of Chesterton to Newman: people react in very different ways to different personas. Who doesn’t (almost instinctively) like the jovial, congenial, always smiling and wisecracking, big cuddly teddy bear Chestertonian type? Who could resist that? But not all men are of that type. It was God’s will that we have different temperaments (and thank heavens for that). Newman may not have been “warm fuzzy” likeable in that vein, but he was no less deeply admired and loved by virtually all who knew him: including many thousands of Protestants in his last 26 years of life. I collected some personal impressions from several people on a Photograph and Portrait Page.

Chesterton was also bitingly satirical, especially about atheists and intellectuals: make no mistake about it. Again, I know a little about that, having compiled a book of his quotations, too! Here is one of my very favorites (I have it on my Facebook profile page):

And those who have been there will know what I mean when I say that, while there are stupid people everywhere, there is a particular minute and microcephalous idiocy which is only found in an intelligentsia. (Illustrated London News, “The Defense of the Unconventional,” 10-17-25)

Or how about this delightful tidbit:

I have frequently visited such societies, in the capacity of a common or normal fool, and I have almost always found there a few fools who were more foolish than I had imagined to be possible to man born of woman; people who had hardly enough brains to be called half-witted. (The Thing: Why I am a Catholic, 1929, ch. 6)

Now, in person (utilizing his charm), Chesterton probably could get away with such withering, acerbic comments, but if one merely reads them (especially without knowing who wrote them), they are every bit as “negative” and as difficult to be a recipient of, as Newman’s barbs. Therefore, in terms of sarcasm considered in and of itself, apart from personality, I see little difference, if any, between the two men.

I agree that Paul is a dazzling writer. Would that he concentrated his rare gift on more defensible and edifying subject matter.

***

***

I’m sorry but I’m afraid there’s a bit of a stitch-up going on here:

a] My initial comments were in response to the nature of the letter being promoted as an exemplary means of dealing with trolls by being non-confrontational[starving the troll], by remaining courteous and presuming and implying inference of best motives.

Thanks for your thoughts. Very interesting and well-stated. We continue to (mostly) disagree.

I agree that Newman’s approach was not non-confrontational. In that respect I am closer to you than to Brandon. I disagree that the leading motive or characteristic was anger. It is simply withering sarcasm in the service of truth and fair play: a thing that both Jesus and Paul did (and Jesus, without sin, as those of us who believe He was God and therefore sinless, hold).

b] I gave no indication whatsoever of imposing a presumption of malice on Newman or even the ontogeny of a feud and vendetta.

That’s pretty remarkable, given the quite loaded (and repeated) adjectives you applied to Newman’s words and alleged interior attitude / motivation. I’m not questioning your report (as you have done to Newman!); I’m saying that granting this (your current interpretation of yourself) to be true, your word selection was exceedingly poor and misleading (not by intent, but by likely result).

I was commenting on the nature of a letter – which I inferred was far from courteous, it was most certainly not devoid of personal insult or appeal to ad hominems and it was not one which implied optimal benignity.

I think many times the line can be very fine between attacking a falsehood or injustice, and attacking the person producing them. It’s true that saying, “you uttered a falsehood” is quite close to (or could be close to) saying, “you are a liar / you are the sort of person who is characterized by the uttering of falsehood.” So it’s a fine line, to be sure, and reasonable folks can differ as to what is going on.

Nevertheless, if we speculate unduly on motivation, then we are in distinct danger of lack of charity towards our subject. I was trying to get beyond mere subjective analysis and reading in-between lines and words, to actual objective reports from Newman himself.

Now, of course, probably every man has a bias towards himself, but if we are to talk about not attacking others and remaining charitable, we must give his words their due weight. You have chosen to ignore all of the primary evidence of Newman’s internal state of mind while dealing with Kingsley and writing the Apologia; instead choosing to remain on almost an entirely subjective plane, which only reinforces my initial impression of your analysis as (largely) mere psychobabble.

c] The only things I said were that this was

[i] composed in anger

This is precisely what Newman denied. You say elsewhere that you don’t want to call him a liar, yet in effect, you do, by continuing to maintain this line. Newman himself denied this four times in just a single personal letter (that I already cited):

“I never from the first have felt any anger towards him.”

“As I said in the first pages of my Apologia, it is very difficult to be angry with a man one has never seen.”

“A casual reader would think my language denoted anger – but it did not.”

“. . . much less could I feel any resentment against him . . .”

(Letter to Sir William Henry Cope, 13 February 1875)

But you know better. You think you “know” that Newman was “angry” and that this was his leading (?) motivation in dealing with Kingsley. This is what I particularly object to, as quack psychoanalysis. Newman says he didn’t feel “any” anger; you say it is primarily characterized by anger, coming from deep within Newman. He even draws a general principle from it: it’s difficult to be angry with a man one has never met. Then he explains how his language might possibly be interpreted as angry, but it was not (yet you continue to say what he denies).

Language and styles of writing can be misinterpreted, in other words. Happens all the time. Believe me, I know, myself, from my 650+ Internet dialogues and innumerable encounters in 31 years of apologetics. Lastly, Newman denies “any resentment”: eleven years after the initial incident.

I am saying: why can’t it simply be righteous indignation of the sort that Jesus exhibited with the Pharisees and moneychangers? That involves no sin whatsoever and is personally justified.

I accept Newman’s words at face value, but you don’t want to do that. Instead, now you have come up with yet another psychobabble theory [seen below] about how Newman supposedly reinterprets his own past actions and writings. It’s extraordinary. Quite interesting and fascinating (I’ll give you that), but, I submit, implausible and unsustainable under logical and historical scrutiny.

If we are content to regard Newman as a bald-faced liar, in reporting about his own interior states of mind (making him some kind of self-delusional, neurotic, messed-up man: the type we see by the millions in today’s society), then you would have a point. But why would we choose that as an explanation?

You emphasize the humanness of Newman (i.e., non-perfection). I never denied that. But in going so far to “prove” that he wasn’t perfect or some cardboard caricature of the popular conception of what a saint is about, you go way too far in the other direction, and end up regarding him (i.e., by the logic of your position, though you deny it) as a bald-faced liar or someone who is such a compulsive liar that he must have a severe neurosis or maybe even psychosis (removed from reality, which is what all mental illness means, to one degree or another).

After all, in your scenario it is an instance of a man strongly denying what you (and apparently you would say, many others, too) regard as perfectly obvious and beyond argument. That is expressly an irrational denial of reality (as you see it): hence, mental illness of some sort, by definition.

&

[ii] not a means [nor I believe was it ever aimed] to either neutralise or pacify – far from being courteous this letter was inflammatory and aggravated the situation by going beyond countering the simple historical/factual detail and its attached prejudicial slur to personal attacks and presumption of motives/capabilities. Not oil on troubled waters but oil on the flames.

I deny this as well, from the knowledge that I have about the man (as a great devotee of his for 22 years, and now compiler of his quotations), but I think it is fair to examine the question more deeply. If you mean merely the first reply, we could look at that in greater detail and determine whether it plausibly entails all these traits that you attach to it.

d] This is the enthymeme/subtext where the misconceptions are arising:

I am perfectly willing to concede that there are all manner of sound, understandable reasons as to why Newman was motivated to write in such a way [e.g. 19 years of calumny, alienation, exasperation over systemic torment at the hands of one’s previous associates etc]. I would seize any opportunity to ameliorate or mitigate Newman’s motives for writing the way he did.

But

[i] Dave A thinks I’m appealing to pop-psychology, imposing classic textbook neuroses upon JHN, diminishing both the issues at hand and the events leading to this fracas as exigent and merely hyperbolised by Newman’s fragile sensibilities – he understandably but erroneously combines two separate comments I made . . .

Yes I do, in a broad sense: not necessarily in every particular as you now describe what you think I was doing. What you write today, in the end, reinforces my interpretation, because you go right back to more (almost embarrassingly, excruciatingly speculative and subjective) psychoanalysis and utterly ignore the objective data of Newman’s own report about himself (that I presented). Thus, my combining of the two motifs seems not to have been far from the mark at all.

. . . in regard to

a] Newman’s tendency to quarrel, sulk, be bitingly acerbic and bear grudges; with

b] The simple fact that this letter is highly vitriolic!

Here you say it is two different things you were talking about. Fair enough (granted); yet nevertheless you seem to combine the two again in how you interpret the data of the Kingsley-Newman dispute and in how you interpret Newman’s response. You still do bring it back to supposed leading personality traits of Newman’s.

And I bring it back again to simply brilliant acerbic satire, that can be done in a way that involves neither personal pique nor anger nor desire to wound the other person.

Again, I can relate to this from many incidents in my own experience, since I’ve been known to be quite a “hard-hitter” and to use rather pointed sarcasm if the occasion warrants. Many times, I have been accused of attacking individuals, when in my mind, I was quite sure that I had no such intent. I was strictly concentrating on falsehoods. But the people involved were “sure” that I had such a motivation, based on the words I wrote (precisely as you do with Newman). I did not (in many of those instances; sometimes, I crossed the line, and would later apologize for having done so).

I’m as flawed as anyone else, but this is my life’s work and I am particularly careful (as a matter of “occupational hazard”) to separate critiques of ideas from that of persons and their motivations. Far as I can tell, I think Newman did the same (as a writer, public figure, and one often embroiled in controversy), and we see that in his later comments about Kingsley the man.

…into an amalgam where a provoked Newman has endured the final straw and has now picked a fight over a triviality.

That was not my opinion . . .

ii] This is not the case. It was solely in response to Brandon’s dismissal of my interpretation of the letter that I stated Newman had a capacity for biting sarcasm and if provoked he could easily use his rapier-like intellect to eviscerate his opponent

Yes he could, and did in this case. I say, however, that it can be and was done, minus the “anger” and other epithets that you attached to it: just as Jesus did the same. I don’t say this because I think Newman was perfect, but because I don’t interpret this particular incident as you do. I don’t see the same things you see. You could argue, I suppose, that I am biased in favor of Newman and am blinded by that (probably guilty to some extent), but then I could say that you are possibly biased against him, for some reason, leading to a more cynical interpretation.

Historical truth comes from different perspectives meeting each other, and that is exactly what we are doing here. I think I’ve offered (at the very least) enough counter-information to cast doubt on your “theory” as the only or most plausible one.

– therefore my interpretation is not axiomatically untenable and not one which can be easily cast aside because he’s the angelic genius Cardinal Newman and ‘blesseds don’t act like that’.

That’s not my argument. I have presented it very carefully (especially after this reply), and it’s not based on “Newman being saintly; therefore he couldn’t have possibly sinned here.” It’s based on what actually happened and how one plausibly interprets it, all things considered.

I do think, however, that one who has been beatified is entitled to be granted enough benefit of the doubt, so as to not be regarded as a bald-faced liar (your casual dismissal of his own report about his own interior dispositions as regards Kingsley). I can hold that without being guilty of holding some sort of pollyannish / childlike view of sainthood.

Brandon’s saying act in certain ways against trolls; using Newman’s letter as an example of how to do it. It’s certainly justifiable to ask if Newman is really emulating the proposed ideal responses?

I would say, in that situation, absolutely. Again, as I alluded to before, the reaction of the English public (otherwise predisposed to be biased against any Catholic) proves the rightness of what he did. They thought he was perfectly justified. Good ol’ English “fair play” won the day. I think that is also objective data that counts for a lot.

The rightness/wrongness/justifiability of his letter is debatable . . .

Perhaps so, but nothing you have given us so far changes my own opinion of it. I think you have failed in arguing your perspective.

– even the proposed etiquette against trolls is contentious; but at present the proposition…

“Act like Newman who did X, Y & Z”

…has become as antinomial as a square circle if Newman instead did A,B & C.

Nothing personal against you! I’m simply critiquing your ideas, that I disagree with, and your ideas ain’t you.

***

BECAUSE Newman didn’t merely attack the argument and the calumny – he moved on to attack the character, worth and motives of those involved.

It becomes personal pique when the attack is moved from what’s said to why is was said. Whether he was justified or not is debatable but please – it’s ridiculous to say he didn’t do what he did.

“..nor would I thank them for it” is scathingly derogatory – analogous to “I wouldn’t waste a bullet on them” or “I wouldn’t pee on them if they were on fire”.

I was recently privileged enough attend a private talk given to the Guild of Blessed Titus Brandsma by a Brompton Oratorian where there were many revelations regarding the internecine conflict between Birmingham and London during the Newman era – it was redolent of the Montagues & Capulets or Antioch & Alexandria.

There’s nothing wrong with admitting that along with Newman’s intensive passion came the baggage of hypersensitivity and on occasions he fell into recalcitrant ‘objective forgiving but never subjectively forgetting”

…and although I’m not going to call Newman a liar or a scoundrel, but he was often quite remiss in revisionism regarding previous dispositions with “I meant no offence” where an incredulous antagonist would respond “no offence given – but much taken!”. Newman didn’t exactly whitewash past confrontations but he was anachronistic in his ‘remembered apprehensions’. There were times where his writing reveals he was obviously furious yet when later recounting the events he quite obfuscatingly opines he wasn’t that upset about it and attempts to make a personal fight into an academic exercise [cum grano salis].

…almost like a retired general recounting past battles at the dining table with somewhat poetic licence.

David A cites Chesterton and I’m reminded of His Short History of England where he appeals to the dappled multicoloured nature of the human soul of historical figures – it isn’t black or white or varying shades of grey but more like a multifaceted diamond where certain facets are more polished or smudged accordingly – where virtues and vices are all at varying hues and translucencies.

Newman was human.

Again, Paul, your theory of Newman’s motivation is at odds with what he himself said about it. For example, in the Preface to the Apologia, he wrote:

But I really feel sad for what I am obliged now to say. I am in warfare with him, but I wish him no ill;—it is very difficult to get up resentment towards persons whom one has never seen. It is easy enough to be irritated with friends or foes vis-à-vis; but, though I am writing with all my heart against what he has said of me, I am not conscious of personal unkindness towards himself. I think it necessary to write as I am writing, for my own sake, and for the sake of the Catholic Priesthood; but I wish to impute nothing worse to him than that he has been furiously carried away by his feelings.

This is his own “meta-analysis.” One either accepts it or not. Or one can choose to read through passages in the Apologia that are tough and hard-hitting, and extrapolate from them some personal pique or ill will, or overarching anger. In so doing, however, one must directly reject Newman’s own report. I can see no compelling reason to doubt the latter.

It’s not like no biographers can be found who concur with this scenario. Meriol Trevor, in the second volume of her two-part biography, Newman: Light in Winter (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1963, 659 pages), states, in writing about the initiation of the public dispute:

Sometimes one feeling was expressed, sometimes another, but all were felt and none suppressed. In spite of this, Newman’s decisions were not determined by his emotions, but taken after deliberation, consultation and prayer. (p. 323)

Others besides the ‘Saturday’ [Review’] critic have called Newman cruel and pitiless to Kingsley. It is clear from his private letters that, though he was indignant at Kingsley’s slanderous attacks and his slippery way of delivering them, he felt no anger against him as a person. He never once attacked Kingsley’s own opinions, or his sincerity. All he did was defend himself, and if his defence was hard-hitting, at least it was fair and straightforward. It was Kingsley who had attacked, and who refused to admit himself in the wrong. And when he replied it was with such passionate hatred that few could admire the performance.” (p. 325)

Trevor refers in the next paragraph to “the heat of his [Kingsley’s] anger” — but as we have just seen, she applies no such anger to Newman in the controversy. Does this not carry any significant weight (the opinion of a leading biographer): along with Newman’s own expressions of his non-anger during the episode?

Wilfrid Ward, in his two-volume 1912 biography of Newman, takes the same view (and this is the guy who is famous for advancing the view of Newman as “hyper-sensitive”). Of Kingsley, he says:

Every line of this pamphlet speaks of an indignant man who is convinced that he has much the best case in the dispute, and who cannot bring himself to conceal his contemptuous dislike for his opponent. . . . the sheer prejudice which led to Mr. Kingsley’s insinuations. (Vol. II, ch. 20, 11)

These views were echoed at the time by Richard Holt Hutton, editor of the Spectator: described by Ward as “a Liberal in politics, until lately a Unitarian in religion, a known admirer of Kingsley, a sympathiser with the Liberal theology of Frederick Denison Maurice” (ibid., p. 4). It was Hutton who held that Kingsley was largely driven by prejudice and misinformation, and that Newman had gotten the better of him.

About the worst that Newman does is call Kingsley a “furious foolish fellow” (Letter to R. W. Church, 23 April 1864; from Ward, v. 2, ch. 20, p. 20), but that much is surely evident from the man’s writings, and readily observed by more objective onlookers such as Hutton. Ward wrote:

One, and only one, adverse criticism did remain permanently in the public mind,—that Newman had been unduly sensitive and personally bitter towards Kingsley. With this impression he dealt in a highly interesting letter to William Cope written at the time of Kingsley’s death,—a letter which completes the story of the writing of the ‘Apologia.’ (ibid., p. 45)

I cited part of this letter before (dated 13 February 1875). Here is some more that is directly relevant to the question of “tone” vs. Kingsley:

I have ever found from experience that no one would believe me in earnest if I spoke calmly. When again and again I denied the repeated report that I was on the point of coming back to the Church of England, I have uniformly found that, if I simply denied it, this only made newspapers repeat the report more confidently,—but, if I said something sharp, they abused me for scurrility against the Church I had left, but they believed me. Rightly or wrongly, this was the reason why I felt it would not do to be tame and not to show indignation at Mr. Kingsley’s charges. Within the last few years I have been obliged to adopt a similar course towards those who said I could not receive the Vatican Decrees. I sent a sharp letter to the Guardian and, of course, the Guardian called me names, but it believed me and did not allow the offence of its correspondent to be repeated.

As to Mr. Kingsley, . . . I heard, too, a few years back from a friend that she chanced to go into Chester Cathedral and found Mr. K. preaching about me, kindly though, of course, with criticisms on me. And it has rejoiced me to observe lately that he was defending the Athanasian Creed, and, as it seemed to me, in his views generally nearing the Catholic view of things. I have always hoped that by good luck I might meet him, feeling sure that there would be no embarrassment on my part, and I said Mass for his soul as soon as I heard of his death. (ibid. pp. 45-46)

Yet more evidence against your general theory . . . It explains much as to tone and also the absence of any resentment towards Kingsley.

***

Sorry but to be brief you’re extrapolating and hyperbolising what I said into a reductio ad absurdum.

I am not referring to the Apologia or the personal affability/animosity levels of the intellectual battle – I’m commenting on the letter itself.

Written in fleeting anger: Understandable and forgivable by being written in fleeting anger.

I don’t, not because he is beatified, but rather, because of:

1) His own report.

2) Opinions of relatively “neutral” observers at the time, like Hutton.

3) Opinions of prominent biographers (Ward, Trevor).

4) The fact that the English public (predisposed theologically and culturally to be hostile) was won over by his self-defense.

5) Analogies to similar misunderstandings about words and supposed motives or emotions lying behind them from my own experience, as a frequent debater and one (unwillingly) often embroiled in controversies.

6) Analogies to Jesus’ non-sinful biting sarcasm (Pharisees, moneychangers). Sarcasm per se is not immediately “emotionally spiteful / malicious,” etc.: let alone sinful.

7) A thing called “righteous indignation” that is perfectly justified in the right time and place, and applies, I think, in this instance.

***

Ok. Start again:Good. You’re not getting very far with your first attempt.

a] When someone responds to a published statement and doesn’t make any attempt to counter it or demand an apology or retraction…

– but instead moves on to imply ungentlemanly conduct by the owners in allowing the editor to publish it and if they wish to be considered gentlemen they should dissociate themselves from it

– together with implying no apology or retraction would be required because they wouldn’t be worth the paper on which they were written because

– ‘nor would I thank them for it’ implies an intellectual and moral opprobrium of both Rev Kingsley and the Editor.

…what may one infer?

That it was a brilliant instance of rhetoric and marvelously understated socratic irony, perfectly fit to the times and the cultural milieu, and utterly justified by the seriousness and absurdity of the charges leveled. He was appealing to the well-established English sense of fair play (as one commenter [in the combox] aptly noted). You live there; you know how that works. Let’s look at what he wrote (it’s all wonderful understatement):

“I should not dream of expostulating with the writer of such a passage,”

[In other words, “it’s not worth it; it’s beneath the dignity of a reply, in and of itself.” But in the long run, answering it had value, as it turned out, post-Hutton’s defense, etc., for the larger defense of Catholicism in England]

“nor with the editor who could insert it without appending evidence in proof of its allegations.”

[In other words, “shame on you for publishing unethical nonsense like this, minus the commensurate documentation, which is in accordance with your own ostensible standards as a respectable periodical.” He’s calling them to live up to rudimentary standards. Mild; perfectly acceptable and justified]

“Nor do I want any reparation from either of them.”

[here I think he is simply implying that he doesn’t wish for it to escalate into some huge personal / possibly legal tiff]

“I neither complain of them for their act, nor should I thank them if they reversed it. Nor do I even write to you with any desire of troubling you to send me an answer.”

[socratic ironic understatement, with a biting sarcastic, “hit-between-the-eyes” undertone. Brilliant . . . He has no need to “thank” them since it is so utterly obvious that it was a wrong and baseless charge, that anyone would expect that a respectable magazine to withdraw it as a matter of course, upon the slightest reflection]

“I do but wish to draw the attention of yourselves, as gentlemen,”

[appealing to English fair play and the Victorian ideal of the gentleman]

“to a grave and gratuitous slander,”

[the heart of the matter, that should be corrected, in accordance with rudimentary Christian ethics: then (very much unlike now) still the leading ethical framework in England]

“with which I feel confident you will be sorry to find associated a name so eminent as yours.”

[attempt to appeal to their better instincts: “surely you don’t want to defend nonsense like this, or be associated with it?!” Do you?” This is why he shouldn’t have to thank them if they withdraw it, because it’s so clearly out of place]

I see nothing here that goes to essential motives of Kingsley or the periodical: only an appeal to their better natures. I have often used such rhetoric myself, and so am quite familiar with it, as I am with socratic irony (Socrates was a huge influence on my thinking and style).

When he doesn’t attack what was said but instead attacks the character and motives of the one who said it, the one who allowed it to be said and his employers?

I think this interpretation doesn’t reasonably follow from what was written, once the rhetorical style is understood. It’s a case of a misunderstanding of genre and attribution of non-existent motivations. But Newman clearly detests the slander and lies, as he well should have: as anyone would have, as the target.

Including an added sideswipe at the publication by mentioning he never read it?

I didn’t see that. Perhaps I missed it, and you could be so kind as to point it out to me?

[Remember how I said look for the extra unnecessary comments made by the English?]

Sure, but you construct an entire substructure of motivation that is unwarranted.

One does not engage in paranoia or apophenia or enter into scurrilous speculative fantasy by inferring that such invective emanates from someone whom is not exactly a happy bunny about the situation.

He was not, nor would you or I be for a second: and I have been massively slandered in public by anti-Catholics. I know very well how that feels. In any event, that doesn’t extend to all the various expressions of alleged opprobrium that you have attached to his interior feelings and thoughts.

b] You say we have the ‘primary hard objective evidence’ of Newman saying he wasn’t angry,

Why do you immediately question that as relevant material? Why is his own word not good enough for you?

and then appeal to the Apologia to corroborate that he wasn’t one for retaliation in fits of pique,

Not only that, but also neutral contemporary observers and prominent biographers.

but invariably reverted to scathing intellectual sarcasm to repudiate and refute his opposition;

I didn’t contend for that (“invariably”?). Now you apparently extrapolate from this one incident to some supposed universal tendency of Newman’s to resort to biting sarcasm at the drop of a hat. This was one specific instance that called for sarcasm, because it was so manifestly ridiculous. There was no “serious” way to deal with such a thing. It had to be dealt with at some level of irony, humor, etc. So we have the famous “in-effect dialogue” back-and-forth: “I never said it!” He was merely extending the method that he used in Present Position of Catholics in England: illustrating the absurd by being absurd: classic rhetorical method in argumentation. Reductio ad absurdum . . .

then imply that it is sheer pop-psychobabble for anyone to suggest he wasn’t being completely honest in his recollection of his disposition that he wasn’t angry and felt no antipathy to his opponents.

The psychobabble lies in the entire analysis you make, that relied purely on your subjective “take” based on his use of sarcasm. You’re only now getting around to interacting with the primary historical evidences I produced, and even now to merely dismiss them with scarcely any objective reason why.

Again, I ask: why is his own clear report not good enough for you? Why are you inclined to doubt it as revisionism or quasi-neurotic self-delusion? I don’t get it. I’d be interested to hear other possible things you criticize in Newman. Perhaps a bias is in play here. I am biased in favor of him; absolutely. He’s one of my big spiritual / theological / intellectual heroes. Do you have some bias against him?

c] Hold on to your hat:

You have Newman as someone who resorts to unemotive, cold, crystal-clear, clinical, logical intellectual scalpel-like dismemberment of his opponents’ position through rational argument laden with sarcasm mocking the academic propositions…no emotional motivation, no letting his temper getting the better of him.

I didn’t claim it was devoid of all emotion; never claimed such a thing at all. That could hardly be the case, since I cited six of his letters about writing the Apologia, where he said he was in great emotional distress indeed, including feeling he would break down, and many crying spells. He was greatly hurt by all the lies said about him, going back some 25 years by that time. He was a sensitive person. Of course he was emotional. Now you’re trying to put thoughts in my head and words that aren’t there.

Your mistake is in interpreting the thing in a very (almost ridiculously, as you continue to go on and on) negative light, with woefully insufficient evidence to do so, and in the teeth of strong counter-evidence of many kinds. You imply this may be a case of “letting his temper getting the better of him.” Thanks again for your candor. There is no evidence of that, unless we say he is lying or deluding himself. He denied having any anger at all, let alone losing it and flying off the handle! We also know that he greatly deliberated and agonized over how to proceed, including repeated recourse to the opinions of a lawyer friend (Badely).

The letter was not written in the fog of a temper tantrum! You have no evidence for that. I guess you simply have a difficult time grasping that such brilliant satire can be written in a state of mind other than that which you have colorfully and variously described as allegedly Newman’s when writing the letter: “fury, venom, contempt, condescension, disdain, vituperation, ad hominem, vitriol, incandescently livid.”

This is sheer nonsense. As I have stated repeatedly, the mere presence of acid satire does not necessarily mean all these other negative emotions towards persons are present at all. They could be (speaking generally now), but not necessarily, and I don’t believe they were, here, because the historiographical evidence is against it at every turn.

You appeal to this letter being an example of classical sardonic intellectual evisceration…

In large part it is classical rhetoric and socratic irony, yes. But I was usually referring to the entire correspondence back-and-forth. That includes the first letter.

not triggered or provoked by distress or fury but rather a stoical righteous indignation at the factual error, the historicism, the slander and the grave offence to all Catholics.

More confusion on your part. He was distressed, but not “furious” in the sense that you opine, with all your various (gratuitous, I think) descriptions. It was righteous indignation, for a very good cause.

And then appeal to Newman himself stating he wasn’t angry.

And you want to dismiss that for some reason. He wasn’t personally angry against Kingsley.

d] I counter:

Although I won’t say Newman was being untruthful, I will accuse him of being somewhat dishonest

A distinction without a difference, and virtually sophistry, but at least you are straightforward about it.

– turning this into an objective paradigm I’ll agree with Newman – of course he wasn’t angry with Kingsley himself – he didn’t know Kingsley – but what I will say is that he was absolutely livid with the eidolon Kingsley who wrote the article.

He was livid about ridiculous lies and slanders. One can be that without the slightest animus towards the person who is the source: even abstractly (since he didn’t know him).

Why do I say this?

Why do I strongly argue that this letter was not a product of clear-headed intellectual sarcasm and was rather the work of someone enraged and letting rip his feelings?

Yes, why? I’m curious. He was enraged: at the lie, not the liar.

To defend the honour of Blessed John Henry Newman!!

Because IF this letter is the product of a cold unemotional intellect…

…it turns Cardinal Newman into a monster!

Fortunately, I have never argued such an absurd thing, so this has nothing to do with my contentions, and amounts to a straw man. He was emotional, but not as you suggest. You get the particulars wrong. I don’t counter your point of view by going to extremes and denying all emotions whatever, but by denying your particular take: and that with objective counter-evidences, not subjective mush, such as you have been specializing in throughout this. I know a little psychology, too, having minored in it in college. I know psychobabble when I see it.

The only justification for him saying the things he said – for his going way below the belt and attacking the motives and characters of the individuals concerned – is to forgive them on grounds of it being a hot-blooded emotional response.

I deny that he did this. The justification is the lie itself (that’s more than enough), and how it was extrapolated in the English culturally anti-Catholic mind to Catholics en masse, and especially to those sinister, jesuitical priests.

If you turn down the temperature and make this a cold, clinical response?

The things he says become appalling, obscene, shockingly reprehensible.

If you are at such a loss for counter-reply that you now must resort to a gross caricature of what I have contended, then I think we are drawing to a close. You ain’t got much ammo left in your arsenal. You seem to be arguing with someone else at this point, not me.

You have the choice of hot-blooded recklessness or cold-blooded callousness.

No I don’t. You’re a victim of your own false dichotomies (which is a typically Protestant — particularly Calvinist — mode of thought). I say it is perfectly justified emotionally passionate righteous indignation, such as the prophets, Jesus, and Paul also expressed. All Christians should be very passionate about wickedness, while refraining from being malicious or hateful to people. Cardinal Newman did that. You seem to think it’s not possible (for you, it has to be hot-tempered tirades or — far worse — calculated cold cruelty). All kinds of things are possible with God’s grace, and we are talking about a beatified man, after all. This is no ordinary man. He had God’s grace all about him.

By trying to defend Newman by excusing his responses as classical intellectual sarcasm – you are inadvertently representing him as a vindictive cold-hearted b*stard who understood very well what he was saying and had no reticence or compunction in saying it.

Now you are becoming merely humorous. I did no such thing. Your mistake lies in assuming that in order to employ classical modes of argumentation one must simultaneously be reduced to an unemotional automaton. I said no such thing; implied no such thing. That comes from you: irrationally projected onto me (or what you think is my argument) with no evidence: just as you are treating Cardinal Newman.

Again, I can draw from my own frequent experiences as an apologist. I’m a very controlled, “cool,” easy-going, even-tempered person (ask anyone who knows me well). I might truly lose my temper maybe every six-seven years: maybe even longer. It’s very rare. Yet I am accused of doing so (strictly by people reading my writings) many times: of having some highly-charged supposed feelings, etc.

Why is that? Well, for the same reason as we see in this situation, I submit: because I am quite (extremely!) passionate and emotional about truth and true ideas and right vs. wrong. I have to be as an apologist, or else I would lack 90% of my motivation (I’m sure Brandon and all apologists understand what I am saying here). We fight and contend for the right and the true, as we understand it in faith, in line with Holy Mother Church.

So I am very passionate about the truth and the good: the very opposite of cold and calculating. Yet I can do this (most of the time; other times I fail, like we all do) without a hot-headedness or out-of-control anger and personal attacks. This is what I am saying that Newman did. Your two options are not the only two. There is also this third option.

Defend him as someone who was hot-headed and his emotions got the better of him and this led him to go too far in attacking the characters and motives of his opponents?

Then you have a lovable forgivable flawed human being.

I defend him according to what I know about him (which is a lot) and the available evidence: none of which leads to your conclusion. Since I’m not bound to your illogically rigid two-choice scenario (monster vs. flawed, lovable truly human person), I can opt for a third choice, even abstracted from the question of Newman’s saintliness. You don’t seem to be able to comprehend this. For you, for Newman to be passionate or righteously indignant, requires some sin in there somewhere. It doesn’t at all.

He wasn’t perfect, and was perfectly human. I recall one letter in my research for my book where I thought he clearly crossed the line in describing or rebuking someone. So my opinion doesn’t come from some idealistic or unrealistic appraisal of Newman as somehow up there with the Blessed Virgin. I’ve already reiterated that at least twice.

So in order to defend Newman against your defence of Newman I have to say in his retaliation he sinned a little…

…because if he didn’t?

Not logically required, as I have explained.

You don’t quite realise that your ‘Newman is sinless in this regard’ defence turns him into one of the biggest sinners possible!!

Not if your two choices aren’t the only ones. You have painted yourself into an unnecessary logical fallacy.

A deplorable desiccated clinically calculating vicious reprobate who rationally determines revenge is always best-served cold.

You have quite a way with words. I wish your logic could attain that same high level.

I’m saying Newman’s response was emotionally heartfelt.

Absolutely. We merely disagree on the particular emotions and where they were directed.

You’re [inadvertently?] arguing it was scarily heartless.

Never did so (not even inadvertently: thank you), and I’m not doing it now.

Thanks for the very vigorous discussion and challenges. It is immensely enjoyable to me, and I love writing anything to do with Cardinal Newman.

***

It’s always a possibility in dialogues on complex subject matter. You have hugely misunderstood my argument. I may very have misunderstood something in yours as well. At least I interact directly with your words, anyway.

Relatively mild?

In what way?

When one attacks the reputation and motive of opponents one should have thought that however ostensibly courteous or to what degree one imputes culpability seems irrelevant – like being a little bit pregnant? Alea acta est even when it’s snake eyes!

Explained in my previous textual analysis of the first letter . . .

Now your reasons for maintaining your position may seem like repeated deathblows upon my argument…

Yes, they do!

..until one realises that they aren’t even dealing with my argument.

Well, we have that experience in common, having just dealt at length with your skyscraper high straw men . . .

1. I deal with Newman denying he was angry in regard to the letter elsewhere and my argument stands – your simple repetition does not provide a counter-argument.

All you did was psychoanalyze his supposed motivations and states of mind in allegedly revising his own prior actions. That’s unimpressive and underwhelming, to put it mildly: pure subjective mush and no more compelling than my proving to you that chocolate ice cream is far superior to vanilla. You ignore his letters and also the opinion of some of his most in-depth biographers.

I don’t buy it. It strikes me as fundamentally hostile to his person in a way that is unfair and unjustified. He caught this type of flak so many times during his life: why not after death, too? It’s the lot of all great and brilliant (and saintly) men.

2. 3. 4 refer to the actual battle itself – not the letter – I already stated I was NOT referring to the battle but specifically this letter.

Fair enough. I wish to. however, include the larger controversy in my own analysis (because most people look at it as a whole). That’s my desire apart from your particular issue of the first letter.

5. Is an appeal to personal experience on being misinterpreted therefore it is quite probable that I have possibly misinterpreted – which is quite remiss of you given that you agree with the nature of the letter!!!

Huh? My argument there was that words can often be misinterpreted insofar as people attribute motivations or states of mind and emotion behind them that do not logically follow (not even temperamentally, for many people). This I have experienced myself, many times (it was an analogical observation; I am very fond of analogy, as Newman was), and it is notoriously common online, with the absence of tone of voice, inflection, expression, body language, laughing, etc.: as innumerable people have noted. In other words, misinterpretation of Newman’s words have, I think, led to false conclusions about his interior state.

We only disagree on the motive behind its writing

That’s correct; and the state of emotion.

– we are relatively congruent in our assessment of what’s being said – we diverge when it comes to the why.

Yes.

Now yes you do proceed to say that there is experience of misinterpreted motive and actuating emotions – but what makes you so dismissive of my capacity to infer Newman’s in this specific letter?

Because I don’t accept speculations on historical matters based on mere subjective hunches (what I called — probably uncharitably in bluntness, but I think accurately — psychobabble). It requires objective evidences. You have provided virtually none of that.

Especially given from my previous argument an interpreted emotional response affords Newman more leniency and a more benign outcome of the actions?

It’s a good outcome in your paradigm, but I think it is illogical, because for some strange and inexplicable reason you allow only two alternatives and there are clearly at least one more, if not several.

Objectively you don’t know me from Adam – and although you make great appeal to the ‘ridiculous’ embellishment of multiple adjectives in my original post as [specious] armchair psychology – you have so far cited nothing to disprove my claim that there was fury, venom, contempt and condescension [all differing predicates – not synonyms] in the letter…except appealing to comments made about the whole battle – not the letter itself

I’ll let readers be the judge of my various arguments made. But as to the issue of the whole episode vs. just the first letter (that you concentrate on), some of my evidence does deal with that. E.g.: “I never from the first have felt any anger towards him” (to Sir William Henry Cope, 13 February 1875). That includes the first exchange. It’s a blanket denial of any personal anger towards Kingsley at any time: which you want to deny (based on, as usual, your assumed psychoanalytical prowess, though I don’t deny that you could conceivably produce what you feel are analogical incidents that bolster your theory).

[sans Newman’s reflection of not being angry – which I refuse to believe as if that were the case it would turn him into a thoughtlessly negligent and irresponsible monster]

This is where it gets so absurd (literally so: in the logical sense). You set up this false and illogical dichotomy of “heartless, unemotional, calculating monster vs. hot-blooded, “human,” lovable guy who let loose with a tirade” — seemingly blind to any other possibilities. Having concluded this, you then don’t allow yourself to even look at historical data with any objectivity because you have already “psychologized” it away in this previous foolish dichotomous analysis.

Thus (you say it straight out: it could hardly be believed otherwise) you can’t (indeed, you “refuse” to) believe he was not angry, because that would (in your fallacious cage you have locked yourself in) reduce him to a monster that you don’t believe is the case. If this is the methodology of some kind of “new historiography” I want no part of it. I think it’s ridiculous. Again, I am talking about your views, not you. We all falter logically: it’s a universal human weakness. When I took logic in college the textbook made it clear that the very greatest thinkers have committed fallacies: even basic ones.

Number 6 – Our Lord’s sarcasm – is an obfuscating irrelevance

Not at all. Obviously, you take a view that the sarcasm expressed is (seemingly without possible dispute in your mind) an indication of boiling personal indignation. It’s part and parcel of your analysis (at least as best I can make it out): the sarcasm is so bad that you feel some sin or shortcoming must be indicated by it.

Therefore, I produce Jesus (as I have many times to folks who think all sarcasm is “bad”) as a counter-example. It’s attacking the premises underneath your analysis, which is utterly relevant, and quite socratic: about as far as it can possibly be (like east from west) from “obfuscating.” You just didn’t get it. Hopefully, now you do.

– need I remind you that God made man said ‘Judge not’ while Newman does a hell of a lot of speculative judging of motives in that letter.

I don’t think he did so, and I have gone through it now, line-by-line. We disagree. I think you get that by a simultaneous reading-in-between the lines what is not provably there on the surface, and by your self-imposed irrational dichotomy that you are confined by.

Number 7 – Righteous indignation DOES NOT JUSTIFY an attack on the character or motives of the persons involved –

I agree. I say that Newman didn’t do that. Biographer Trevor (already cited) didn’t think so, either: “He never once attacked Kingsley’s own opinions, or his sincerity. All he did was defend himself”. Newman expressly denied that he attacked his motives in the Preface to the Apologia: the best possible place for him to reiterate that: “I wish to impute nothing worse to him than that he has been furiously carried away by his feelings.” But you “refuse” to believe that because it somehow magically (certainly not logically) turns Newman into a hideous beast and “monster.” Right. That’s why I think it must go back to a fundamental misunderstanding of sarcasm (which is why I cited the famous examples of Jesus and socratic irony).

it would coerce one to vociferously make every attempt to refute the claims made – not to simply refer to it as slander and spend the rest of the time attacking the accusers rather than the accusation.

At length that was precisely what Newman did. At this early juncture, he didn’t yet know that Kingsley was to dig in and get even more ridiculous and stubborn, and tried to get a simple retraction and be done with it. After deliberation and doubt, he saw the unique, golden opportunity that presented itself to defend primarily the Church; secondarily his own honesty and integrity. I’m sure glad he did. We have an absolute classic as a result, and widespread admiration of the man, partly as a result of the Apologia (also, Idea of a University, Essay on Development, Parochial and Plain Sermons, and Grammar of Assent . . .).

If Newman lost his temper

There is no evidence that he did so, and lots of counter-evidence.

and launched an ostensibly civil but blatantly antagonistic tirade it makes him look like a human being – if his actions are equivocated away as merely intellectual sarcasm it makes him more inhuman than can be conceivable.

Dealt with previously . . . fascinating take, but in my opinion dead wrong and illogical, as to the two starkly contrasted choices you seem to erroneously think are the only ones available.

But if you are so fond of psychology, I would highly recommend Grammar of Assent as an example of rather spectacularly nuanced and complex psychology as well as philosophy of religion.

After that, maybe you’ll perceive the possibility of more than two choices only in this instance.

***

On my part or Newman’s?

Either Newman was angry when he wrote the letter or he wasn’t – that is an either/or – that is a dichotomy. Nothing to do with calvinism or a protestant apprehension.

That much is logical and uncontroversial. What is illogical is your insistence that he could only be fighting-mad / temper tantrum angry at Kingsley and not merely righteously indignant over his slanders, minus the element of personal animus. The dichotomy I referred to is your completely arbitrary two choices only: not merely anger vs. non-anger.

Attacking the accusers rather than the accusation is a prime indicator of anger – that’s basic psychology – not mere psychobabble – and to retort your having studied it as a minor – I studied it as two minors, a major and lectured in it!

Good for you. Again, no one is denying that attacking the accuser would indeed indicate that. I deny, of course, that he attacked Kingsley personally.

Now you repeatedly appeal to it being classical socratic irony

In part, for sure.

but I contend this is not being utilised against the accusation but the accusers – this makes it, to revert to anglicisms, “bang out of order!” – It’s not English fair play – it’s simply not cricket old bean…

And we continue to disagree on that. The difference is that I have Newman’s self-report and at least two of his major biographers’ opinion on my side. You have produced nothing except your own opinion.

You dismiss this – swathingly equivocating this plain and simple fact that the accusers’ reputations and motives are the central theme – by appealing to a justifiable use of classical sarcasm precepts – but this doesn’t hold water – and even if it were the case it doesn’t stop Newman from being a cad, a bounder, and acting in a thoroughly unjustifiable way.

Is this what you think about his actions, or are you just saying this is the logical outcome of my partial recourse to socratic irony as an explanation?

Now you’re suggesting I’m imposing an utterly unnecessary subtext of Newman being necessarily angry to write in such a way; to which I respond that if he wasn’t angry when he wrote it there’s no excuse for what he wrote.

Back to your two choices. For the life of me, I don’t get why you want to fight to the death on such an indefensible hill.

You may make some vainglorious attempt

Interesting choice of descriptive word there . . .

to appeal to righteous indignation and even make some futile analogy to biblical characters

I get the distinct impression that you don’t care at all for being disagreed with. It’s a very common trait.

but that IS simply ludicrous – Newman was attacking reputation and motive – not the nature of what was said

Right. And he is because you say so: minus any back-up from insignificant and irrelevant figures such as, say, two of his major biographers.

– and to fall back on Newman realising that it would be futile to make the attempt – it does not remove the fact that he went beyond the pale by instead of countering the message he went for the throats of the messengers.

So you say.

An action which I repeat – is understandable if wrought in anger, but deplorable if written in a coldly clinical rational manner.

Yes, you have repeated that enough times by now.

Why you can’t accept this simple proposition is frankly beyond me – if he’s angry he’s guilty of a minor indiscretion – if he’s not angry he’s instead indicted for a significantly graver transgression with no mitigation.

Not all anger is tantamount to sin. It looks to me like this is one such instance. It’s not written in stone or absolutely proven, of course (very few things can be in any field); just my best interpretation, based on all I have presented and my knowledge of Newman the man.

…and here comes the doozy – you appeal to having a bias towards Newman and being a highly well-read expert

I didn’t claim to be an expert: only a devotee. I specifically denied what you now (curiously) say I claim, writing: “I don’t claim to be an expert on him: I simply collected his quotations.” Nor is admission of bias any sort of “appeal” (?!?!). I was simply being straightforward and transparent: full disclosure if you will.

[not having a clue how experienced or informed or how endeared or antipathetic I am to Newman

Yes, exactly, which is why I asked you if you had a bias (not knowing: which is generally why people ask a question to begin with! DUH!).

– but this doesn’t prevent you attempting to throw an apophenic ‘alternate agenda’ onto my motives for maintaining my position.

Not at all; I simply asked a question, which, as usual, you have not answered. Maybe you do below or in your later reply (I am answering as I read, as is often my custom). But if you don’t, I have no choice but to conclude that you believe you are above the possibility of bias.

[believe it or not my Bishop attempted the same ludicrous ploy only a fortnight ago – instead of trying to counter what I was saying he accused me of having a hidden agenda [together with an appeal to the majority disagreeing with my position and then the appeal to ‘you’re upsetting everyone’] – it was childish then and it’s childish now – it’s a sophistry too far and might work for third party readers but it won’t prevent me from staying resolutely on-track]

I did no such thing. since you say I did the “same” as your Bishop and he “accused me of having a hidden agenda” then you think I am doing this, too, but I never did! Here is what I wrote:

You could argue, I suppose, that I am biased in favor of Newman and am blinded by that (probably guilty to some extent), but then I could say that you are possibly biased against him, for some reason, leading to a more cynical interpretation.

That was a mere hypothetical, rhetorical remark. Big wow.

I readily admit my bias, and merely allude to the possibility that you may have one, too, which is utterly uncontroversial, at least in my mind, because I believe that all people have biases when they approach just about any topic. I asked questions. But you’re answering very few of my questions:

Again, I ask: why is his own clear report not good enough for you? Why are you inclined to doubt it as revisionism or quasi-neurotic self-delusion? I don’t get it. I’d be interested to hear other possible things you criticize in Newman. Perhaps a bias is in play here. I am biased in favor of him; absolutely. He’s one of my big spiritual / theological / intellectual heroes. Do you have some bias against him?

Rather than simply answer good faith questions, you choose, rather, to charge that I am “accusing” you. I had nothing to do with your Bishop the other night. You’re capable of separating me from him, I’m sure.

..and yet again you hyperbolise – of course I meant that [from your contention] whenever he resorted to an intellectualised personal attack he was adopting a socratic irony – not that he always engaged in it at every opportunity.

Alright.

..and yet again you persist in maintaining that I am portraying everything in a highly negative light and unjustifiably blackening Newman’s character by imposing on him a hypersensitivity and diva-like ‘b*tchiness’ – all of this concocted by ‘self-help book’-level amateur-psychoanalysis.

It would greatly help me, and other readers (and help your presentation) if you would: 1) explain what I find puzzling (and perhaps several others, do, too); 2) actually answer my perfectly sincere questions rather than moan and lecture and attribute ill will to me as well.

When to an objective reader it’s quite apparent that I am actually making every attempt to rescue Newman’s reputation by arguing his resorting to character assassination was in a fit of pique – not as part a level-headed calculated plan of action.

That aspect is clearer now that you have explained it (which goes back to my last comment). But his reputation didn’t have to be rescued in the first place. If you’re interested in rescuing someone you should defend ol’ Kingsley. His reputation (at least as a fair-minded, charitable person) was shot, by the consensus of Victorian England.

You contend that instead of being either it’s merely biting satirical genius evoked from justifiable righteous indignation – and if I can’t apprehend and comprehend that’s what Newman’s benignly doing it’s the fault of my ignorance or stupidity or my simply not being familiar with the luxuriant majesty of the socratic method [and I don’t suppose my having lectured a course on the ethics within Plato’s Gorgias will grant me any remission?]

It’s clear that you are a thinker; as a thinker, you know full well that the best thinkers can sometimes be illogical. Perhaps you (as an exception to the rule) are spared by the grace of God from ever falling into what all of us mere mortals have done at one time or another. This is all I said: you were thinking illogically in that one respect. If that wounds your intellectual pride, so be it. We all need that, too, now and then. I never used the words “stupid” or “ignorant” or implied any such thing in any equivalent terms. I have been quite hard, though, admittedly, on your tendency to psychoanalyze Newman in the most excruciatingly specific fashion.

Far from Newman being right to attack characters and motives – I maintain he was in the wrong.

I deny the premise, of course.

Now either he’s excusably wrong by it being actuated by anger; or he’s inexcusably wrong by some twisted self-justification that it’s acceptable to resort to such methods.

Back to the rigid two-choice model again. Very odd . . .

The main bone of contention between us is that Newman could justifiably attack – on the proviso that it’s under some quasi- protective umbrella of utilising a timeless rhetorical mechanism.

To which I’ll reply with some anglo-saxon epithets:

“That’s b*llocks because it would still make Newman a w*nker”

…and I’ll defend Newman against your defence-no-defence of him until the sun grows cold.

Right. Obviously this dialogue is nearing its end (assuming it ever was a dialogue, which is getting more difficult to believe with each entry). I think it could have been a very fun exchange between two people who have a differing interpretation. It is now rapidly descending to the acidic level of so much talk on the Internet (that made me forsake discussion boards for good nine years ago): what a pity and a crying shame. But I have truly enjoyed it up till this point.

***

Oka] Perhaps you are unaware of the difference between the grammatically correct “nor should I thank them for it” and the antagonistic English turn of phrase “nor would I thank them for it” [e.g. I wouldn’t thank you for champagne – it gives me a headache]. To any English reader this goes beyond a literal reading to one where far from saying an apology/retraction is not wanted – Newman’s implying it would be worthless by being inauthentic and insincere. Thus attacking the reputation/motivation of Kingsley and the editor.

Interesting. Can you produce for me anyone besides yourself who thinks this and draws the same conclusion? I’d be very interested in seeing it.

b] I am certain you have grasped the irony of Newman referring to them as gentlemen rather than Sir – implying far-from- gentlemanly conduct – either willed or a fruit of negligence.

I already gave my interpretation of that, which I think is plausible enough (as far as such things can be).