Patristic & Later Catholic Tradition & Contrary Early Heretical Sects’, Protestant, & Modernist Corruptions of It

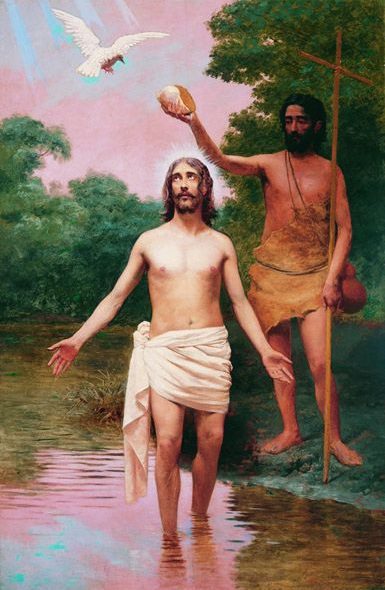

Baptism of Christ (1895), by José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior (1850-1899) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

* * * * *

This post is a follow-up to a controversial piece I wrote two days ago: “Young Messiah” Denies Christological Certainties. See also earlier related papers of mine: Jesus Had to Learn That He Was God? and Biblical Evidence for Jesus’ Omniscience. I will be drawing all of the material below from a wonderful doctoral dissertation that I was delighted to discover last night, entitled, The Boyhood Consciousness of Christ: A Critical Examination of Luke 2:49 (Fr. Patrick Joseph Temple, S.T.L., New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922). It is available in its entirety online (thank heavens for Google Books!).

Luke 2:40 (RSV) And the child grew and became strong, filled with wisdom; and the favor of God was upon him.

Luke 2:49 And he said to them, “How is it that you sought me? Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?”

Luke 2:52 And Jesus increased in wisdom and in stature, and in favor with God and man.

Everything below will be from Fr. Temple’s book, save for the all-capitals subtitles, which I have added. I won’t bother to document the primary source information. For those relative few interested in that, it may be easily accessed in the online text, by a search (or a general online search using the cited texts). I have added italics for Latin citations and book titles. The text below may be considered an abridgement.

* * * * *

CHURCH FATHERS AND LUKE 2:49

[T]he Fathers are unanimous in the view that Jesus at twelve years of age revealed His real Divine Sonship; the Latin Fathers are clear and explicit on the point, and the Greeks go beyond this, nearly all using the text, Luke ii. 49, to defend or demonstrate Christ’s true Divinity.

CHURCH FATHERS AND LUKE 2:52 / KNOWLEDGE OF THE YOUNG JESUS

More direct is the evidence from the statements of the Fathers on the question of the increase of Christ’s knowledge and their explanations of Luke ii. 52, “and Jesus advanced in wisdom . . .” As to how “Jesus advanced in wisdom” the Fathers are divided, some of them holding that the text merely has reference to external manifestation of wisdom, while others claim it means that Christ increased “according to human nature.” But all insist that according to His divine Nature He knew no increase. For instance, Athanasius writes, “it was only His human nature that advanced; Wisdom Himself did not advance, rather He advanced in Himself” . . .

We have such assertions as that of Clement of Alexandria, who says of Christ, “for Him to make any additions to His knowledge is absurd, since He is God,” and that of John of Damascus, who states that those who assert there was an increase of wisdom and grace in Christ “deny that He enjoyed the Hypostatic Union from the first moment of His existence.”

That Christ had no development, but was perfect from the beginning, is stated by some of the Fathers. Clement of Alexandria asks, “Will they not own, though reluctant, that the Perfect Word born of the Perfect Father was begotten in Perfection, according to economic fore-ordination?” Explaining that “wisdom and age” were only gradually evidenced, Gregory of Nazianzus asks,”How could He become more perfect Who from the beginning was perfect?” . . . That Christ was a perfect man already in the womb (perfectus vir in ventro femineo) was stated by Jerome. And he also states that His infancy was not prejudicial to His Divine wisdom, “infantiam humani corporis divinae non praejudicasse sapientiae.”

Augustine holds that ignorance and mental weakness were not in the Infant Jesus, “… quam plane ignorantiam nullo modo crediderim fuisse in infante illo, in quo Verbum caro factum est, ut habitaret in nobis, nec illam ipsius animi infirmitatem in Christo parvulo fuerim suspicatus, quam videmus in parvulis.”

These Fathers, attributing no ignorance and no mental development to the Christ Child, would imply the interpretation of real Divine Sonship in the first recorded words.

APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS OF JESUS’ CHILDHOOD

We shall have occasion to mention the Protevangelium of James, the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, the Childhood Gospel of Thomas, and the Arabic Gospel of the Childhood.

These Apocryphal writings may contain authentic material in the additions to the narratives of the Gospels, but in this respect their value remains problematic, and consequently slight. The chief and great value of the Apocryphal Gospels is that they reflect the views of the times in which they were written and extensively read. Nearly all the Apocrypha were written with a deliberate dogmatic purpose and even those which were not, are “doctrinally significant.” The Childhood Gospels, as we have them, were written in the interests of orthodoxy, and their value is enhanced because of their remarkable popularity, especially in the East.

What do we find in these accounts of Christ’s Childhood? They most explicitly and emphatically testify to the Virgin Birth of Christ. They attribute wonderful innate miraculous power to the Child Jesus, — having His “every word accomplished,” and ascribe great preternatural knowledge to Him. The PseudoMatthew, the Gospel of Thomas, and the Arabic Gospel mention three occasions on which the Child Jesus was taken to school, but on each occasion it was He who was the Master, giving evidence of preternatural knowledge. They witness to Christ’s real Divinity as a child; they have this stated by others, but what is more significant for our purpose, they represent Him as testifying to His Divinity and Divine Sonship. For instance, the Gospel of Thomas (first Greek form), III.: “I am here from above — as He that sent Me on your account has commanded Me”; (second Greek form), VI. “I am before the ages”; (Latin form), VI. “and before all I was Lord . . . and My Father hath appointed this …”; in Pseudo-Matthew, XXI. “that one of thy branches be carried away by My angels, and planted in the paradise of My Father.” According to the Arabic Gospel, I., Jesus says from the cradle, “I am Jesus, the Son of God, the Logos whom thou hast brought forth as the angel Gabriel announced to thee; and My Father has sent Me for the salvation of the world.” So that if the Apocryphal Gospels of the Childhood reflect the views of the times in which they were circulated (and in regard to doctrine they certainly do), then in these early centuries it was held that Christ as a Child was conscious of His mission, Divinity and Divine Sonship. They certainly do not reflect any tradition of a growth or development of His Self-consciousness, or that at a certain stage of His life He awoke to the consciousness of His Divine Sonship. They vividly depict Him as wielding miraculous power and fully conscious of His Nature and Personality, and this as a Child.

The Arabic Gospel of the Childhood is of comparatively late date, but nevertheless important because it is a translation of a Syriac original; because of its wide circulation, and the great emphasis it places on the Child Jesus’ Divinity and Divine self-consciousness. As we mentioned, this work represents the Child Jesus shortly after birth as proclaiming His Divinity and mission; . . .

Since the Apocryphal Gospels of the Childhood cast sidelights on what people thought of Christ in the early centuries, they certainly afford widespread evidence for the view that Christ as a Child was fully conscious of His Divinity, for the view that in His first recorded words He expressed true Divine Sonship. If there is any one doctrine emphasized in these Apocrypha, it is the doctrine of a Child born of a Virgin, possessing Divine powers and Divine knowledge, and this doctrine implies that the words “My Father,” in which the Boy Jesus referred to God, were taken literally.

Now in regard to doctrine, these Apocrypha are orthodox. They could not become so remarkably popular if they contained fundamental doctrines opposed to the opinions of the time. As Findlay says, “The Childhood Gospels stand in the main current of ecclesiastical doctrine in their view of the Person of Christ.” So that we have early and widespread evidence that the view of the Early Church was that Christ did not undergo any development in His Divine self-consciousness, that as a Child He was conscious of His Divinity and Divine Sonship, and hence that His words, given in Luke ii. 49, express real Divine Sonship.

The objection that the Apocryphal Gospels were rejected and condemned by the Fathers does not touch what we have said. The latter, it is true, recorded their antipathy for the “false and wicked stories” and “ludicrous miracles” recounted in these writings, but they do not object to the doctrine which shines through almost every page of these writings, the Child Jesus’ Divinity and Divine self-consciousness. If this was false and opposed to the received tradition, it would be the first thing the Fathers would attack and condemn.

CONTRARY EARLY ERRONEOUS OPINIONS OF A DEVELOPING CONSCIOUSNESS OF JESUS

There is no evidence, in the early centuries of the Christian era, of any explicit denials of the view that Jesus, in the first recorded words, expressed real Divine Sonship. A denial, however, is implied in the various heresies of that period which denied the Divinity of Christ and taught that Jesus, a mere man up to his thirtieth year, was at baptism indued with a higher personality.

Cerinthus, a contemporary of St. John, held that Jesus was a mere man born of Mary and Joseph, and professed the view that “after His baptism, Christ descended upon Him in the form of a dove from the Supreme Ruler, and that then He proclaimed the unknown Father and performed miracles.”

Likewise, maintaining Jesus to be the son of Joseph, Carpocrates (beginning of second century) thought that “a power descended upon Him from the Father, that by means of it, he might escape from the creators of the world.” We do not know what Carpocrates’ view was, as to when this power came on Jesus; he may have held it was at the baptism.

According to Irenaeus, the opinion of the Ebionites in respect to the Lord are similar to those of Cerinthus and Carpocrates. Epiphanius says they held that Christ came upon Jesus, the mere man, at His baptism, when the Holy Ghost, in the form of a dove, descended upon Him. The Christology of the Elkesaites resembled that of the Ebionites and Cerinthus: Jesus, the son of Joseph and Mary, became Divine after baptism, by union with the Aeon Christ.

We know from Tertullian that the Valentinians (Valentinus died about 160) held that upon Christ the natural Son of the Demiurge (born through the Virgin, not of her) “Jesus descended in the sacrament of baptism, in the likeness of a dove.”

All these early views, implying a denial of the Fathers’ interpretation of Luke ii. 49, were heretical. They were condemned by synods; they were refuted by orthodox writers. The fact that the Church looked upon these views as heretical intimates that the contrary view was regarded as orthodox. It is an indirect indication that the view of the early Church concerning Luke ii. 49, was the one expressed by the Fathers in their comments on the passage.

DOCTRINAL HISTORY: 9TH TO 15TH CENTURIES

John Scotus Erigena (ninth century), a forerunner of the Scholasticism of the Middle Ages, held that as Christ was the Wisdom of the Father to Whom nothing was hid, and as He had accepted a stainless human nature (incontaminatam humanitatem), He never suffered the ignorance inflicted as a punishment on fallen man; but from His very conception He knew Himself and all things and could speak and teach (confestim, ut conceptus et natus est, et seipsum et omnia intellexit, ac loqui et docere potuit). This doctrine presupposes the view of real Divine Sonship as expressed by Christ in His first recorded words.

The first writer of a Summa Theologiae incorporating Aristotelian philosophy, Alexander of Hales (+1245), maintains that Christ did not assume ignorance, did not learn anything from angels, but enjoyed a threefold knowledge: the Beatific Vision, uncreated knowledge, and the knowledge of experience. In a certain kind of the latter knowledge, Christ made advance; the rest He had from the beginning.

St. Thomas of Aquin (+1274), who laid down the lasting lines of Catholic theology, has a treatise on “The Perfection of the Child conceived” in which he states that “Christ, in the first instant of His conception, had the fulness of sanctifying grace, the fulness of known truth, free will and the beatific vision.” In his treatise on Christ’s knowledge St. Thomas says, that as man Christ had a threefold knowledge, the Beatific Vision, infused knowledge, and acquired knowledge; in the last alone He made progress.

Dionysius the Carthusian (+1471) taught, that from the first moment of His conception Christ was a perfect man, that he was perfect “not by reason of His age, but on account of the fulness of grace, the eminent degree of virtues and the perfection of wisdom,” and that Christ made no advance in these excepting in regard to the exercise of them (sed quantum ad exercitium).

MODERN AND MODERNIST ERRONEOUS VIEWS OF CHRIST’S CONSCIOUSNESS

Before the rise of modern rationalism, there was practically only one view professed in regard to Christ’s reference to His Father in Luke ii. 49, — the view of real Divine Sonship. Now there arises a variety of views; and among a certain class of scholars there is a definite break with the past. The reason for the great departure and the wide divergency of opinion is to be found in the a priori rejection of miracles. This rejection led some to deny the genuineness and historicity of the early chapters of St. Luke, and the account of the Boy Christ; it led others to explain the account and the first recorded words in a natural sense; it occasioned the theory of a gradual growth or development in Christ’s view of Himself.

On account of these factors, the rejection of the miraculous, the explaining Christ’s first words naturally, the attempting to trace a gradual development of His self-consciousness, there is among modern scholars almost every shade of opinion in regard to the degree of relationship to God that the Boy Christ expressed in His words.

The most extreme view of Christ’s first self-interpretation, is the view of ordinary Israelitic Consciousness. Certain scholars claim that Jesus’ words could be said by any ordinary Jewish boy; that they contain no hint that the speaker considers Himself the Messiah; that they express no special relationship with God; that the sense in which God was called “Father” is the sense in which any ordinary Israelite of that day spoke of God as “Father.”

The first to attempt to trace a development in the self-consciousness of Jesus and thus to introduce this modern problem was Karl Hase (Life of Christ, 1829). He held that in His childhood Christ had no Messianic consciousness. Being uncertain whether Christ became fully aware of His mission before His Public Life, he says that the first words indicate “an unpausing development” showing “the same sense of the nearness of God in a purely human and childish form which is the idea of His life.” Gess contends that in no “exceptional sense” Jesus said “the God of Israel” is His Father.

With the exception of a few extremists who hold that Christ never announced that He was the Messiah, and with the exception of a few who hold that it was only toward the end of the Public Ministry that profession of Messiahship was made by Jesus, the bulk of negative scholars date the dawn of Christ’s Messianic consciousness at His baptism.

Others, in fact the majority of these scholars, take for granted the unhistorical character of the Temple episode and deliberately overlook Christ’s first words when treating of His self-consciousness; such as Harnack, Wernle, Guinebert, Bacon, Weinel, Schweitzer. This is also done in some special treatises on Christ’s self-consciousness, such as those of Baldensperger, E. Schurer, H. Holtzmann, Spaeth, Holtzmann, von Sodon, Volter. Also a number of moderns, when considering Jesus’ earliest recorded sayings, hesitate and are not willing to express an opinion, and others according to their interpretations see very little self-consciousness therein expressed.

Somewhat different from the view just described is that held by another class of modern scholars, who say: Christ’s first words would not be used by an ordinary Jewish boy; they indicate that the Boy Christ had an exceptional self-consciousness, expressing a very special relationship to God, a conception of personal sonship without parallel in previous history. But this sonship was only religious, moral, ethical, an intense feeling of love and devotion; it was not real Divine Sonship, nor did it denote messianic consciousness, which arose later.

Certain modern scholars claim that Jesus’ earliest recorded words express Messiahship, yet nothing more than Messiahship. Some of those deny the genuineness of the words, others contend that only the dawn or first glimpse of Messianic consciousness is expressed, while others claim that full assurance of Messiahship is expressed.

Certain modern scholars, while denying the genuineness of Luke ii. 49, yet state that the text itself as it stands expresses Messiahship. This is the view of Paulus, Strauss, Bruno Bauer, and Loisy.

Other scholars attribute to the twelve-year-old Jesus the beginning of Messianic consciousness. For instance, Edersheim characterizes the state of mind of the twelve-year-old Boy “the awakening of the Christ consciousness . . . partial, and perhaps even temporary.” After seeing in Luke ii. 49, “the breaking forth of the consciousness of Divine Sonship” Meyer adds in a note, “at all events already in Messianic presentiment, yet not with the conception fully unfolded.” The passage is called by Ramsay “a remarkable instance of the young Boy’s awakening consciousness of His own mission.” While de Pressense writes that during this visit of Jesus to the Temple He “perhaps for the first time became fully conscious of the greatness of His mission,” yet in the next breath he calls it a “great moment in the development of Jesus, by revealing Him to Himself.” A. T. Robertson, referring to Christ’s saying “as the keyword to His after life and teaching” and as expressing a most special relation with God, yet attributes to the Boy Jesus a “dawning Messianic consciousness.”

There are modern scholars who interpret from Jesus’ first words that there is expressed the dawning or beginning of consciousness of a real Divine Sonship. This Divine Sonship is variously viewed and is frequently diverse from orthodoxy.

The dawning consciousness of real Divine Sonship is the view of Olshausen, who says that the event in the Temple was the moment when Christ “became aware of His exalted Divine nature,” that there His mental development ripened “into the clear knowledge that He was the Son of God, and that God was His Father.”

CONSERVATIVE PROTESTANT VIEWS

As to the non-Catholic scholars, in a general way it may be said that the view of conservative Protestants concerning Christ’s self-consciousness is as follows: Like everybody He was born an “unthinking infant.” As soon as He reached the age of reason, that is, long before His twelfth year, He became conscious of His Divine Sonship, and in the Temple He gave expression to this consciousness.

Catholic scholars of the modern period unanimously take the position that, in His first recorded words, Jesus expressed the full consciousness of His real Divine Sonship. . . . It is implied by the thesis defended in many theological works, that Christ from the first moment of His conception enjoyed the infused knowledge, . . .

In modern times there have sprung up five other views; — the beginning of real Divine Sonship, a mere Messianic consciousness, the dawn of Messianic consciousness, a special ethical Sonship, an ordinary Israelitic consciousness. With the exception of the last mentioned, which would be implied by certain early heretical opinions, these modern views have no precedents or parallels in previous history.

EXAMINATION AND EXPOSITION OF LUKE 2:52

The meaning, then, of verse 40 is: The Child (referring to Jesus who was previously mentioned as forty days old) grew and got strong, filled with wisdom (or being filled with wisdom) and the grace of God was in Him. It is ordinary to say of a child that he grew and got strong; but is it ordinary to say of a child that he was filled with wisdom (or became filled with wisdom) and the grace of God was in him? Was this said of any other child? Compare verse 40 with a somewhat similar statement made by the same writer concerning the growth of the Baptist, Luke i. 66, 80. It is said of both John and Jesus that they grew. It is stated that John got strong in spirit, while Jesus got strong, filled with wisdom or being filled with wisdom. That the hand of God was with him is asserted of John, while of Jesus, that the Grace of God was in Him. Strong in spiritual zeal, — this characterizes the early years of John’s life as well as the later; as a Child, Jesus is filled with wisdom and has in Him the Grace of God. Luke brings out a marked contrast between the two, indicating the superiority of Christ.

St. Paul states that in Christ are “all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge,” Col. ii. 3, and (Col. ii. 9) in Him “dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead corporally.” And St. John declares the word made Flesh to be “full of grace and truth” (i. 14). Closely corresponding to these, is the statement of Luke that Jesus as a Child was “filled with wisdom and the Grace of God was in Him.” This is by no means an ordinary thing to say of a child. Whether we read “filled with wisdom” or “being filled with wisdom” in this verse, it is a most extraordinary thing, and cannot be explained naturally, for men have to spend years of hard study before they can hope to be filled with wisdom.

Advance in wisdom would ordinarily imply the acquiring of new wisdom. Does it here? What is the force of the word “advanced” here? . . . the Evangelist does not use the word to “increase” or “develop” but employs a word which means to advance, to proceed, and which in itself does not imply intrinsic increase to the subject. Then it should be remarked that he does not say “in His wisdom, in His age, in His favor with God and men,” but he uses these words generically suiting the idea . . . An incident of Jesus’ twelfth year had just been described and St. Luke, wishing to span eighteen years of Christ’s life, writes that He advanced in age. “He continued along the road of age” is the concept brought out by this verb, “to advance,” . . .

Does “advance in the favor of God” mean that the amount was added to every day? Evidently not, nor does it mean that as His age or stature increased, so His favor with God and men increased.

All Catholic theologians are agreed that Christ did not intrinsically increase in grace, v. g. Pohle-Preuss (Christology, 237); and the Fathers and theologians explain Lk. ii. 52, “merely as an outward manifestation of sanctifying grace.” Christ yet unborn was “holy” according Lk. i. 35.

He already possessed the favor of God (40); the verb employed, meaning simply to advance, expresses this idea (and need not express any more), that as Jesus continued along the way of age or stature, so He continued along the way of favor with God and men; He continued to perform acts which won the approval of God and men.

Even as a little child Christ was filled with (or was being filled with) wisdom. Does, then, the expression “advanced in wisdom,” in verse 52, signify that Christ continued to increase His amount of wisdom? Since Jesus already displayed wonderful understanding and knowledge, to hold that His wisdom increased daily would necessarily require one to hold that He became more wonderful every day — a view which is rejected by all. St. Luke does not write “Jesus increased in wisdom,” but “Jesus proceeded in wisdom.” He continued along the road of wisdom, in other words, He continued to do wise acts.

Employing the figure of speech known as zeugma, St. Luke could use a verb signifying real increase in age or stature, yet not entailing this in regard to wisdom and grace. The verb that he uses means simply “going forward” and does not in itself include increase to the subject.

St. Cyril of Alexandria writes concerning Christ’s display of knowledge before the Doctors, “see how He advanced in wisdom through His becoming known to many to be such.” We also hear such explanations of vs. 52 as that of Ward, who says that “advanced” means “not that His knowledge intrinsically increased, but that it gradually declared itself more and more to those among whom He lived.”

Certainly we hold that Jesus’ experimental knowledge increased since He was truly man and had human faculties, . . . Christ possessed a threefold knowledge: (1) that derived from the Beatific Vision of God, (2) infused knowledge, and (3) acquired or experimental knowledge. Concerning the first two kinds it has always been held that there was no increase, concerning the last theologians have not been unanimous. St. Thomas at first (III. Sent. Dist. XIV.) held there was no increase, but afterwards he changed his mind and explained the matter thus: “Both the infused knowledge and the beatific knowledge of Christ’s soul were the effect of an agent of infinite power which could produce the whole at once; and thus in neither knowledge did Christ advance, since from the beginning He had them perfectly. But the acquired knowledge of Christ is caused by the active intellect which does not produce the whole at once, but successively; and hence by this knowledge Christ did not know everything from the beginning, but step by step and after a time, i.e. in His perfect age: and this is plain from what the Evangelist says, viz., that He increased in knowledge and age together” (Sum. III. Q. xii. Art. 2 ad 1). This view is taken by many present day writers: Janssens (Tractatus de Deo Homine, I. 473), Hurter (Theologiae dogmaticae Compendium, II. 461, Maas (Knowledge of J. C, Cath.Enc.), Vonier (Personality of Christ, 95 ff.), Pohle-Preuss (Christology, 247-277), Coughlan (De Incarnatione, 146-167), Lepicier (De Incarnatione Verbi, 395-472).

THE QUESTION OF JESUS’ FORMAL (?) EDUCATION

These twelve verses [Lk 2:40-52] contain the only evangelical account of nearly thirty years of the Master’s Life. It must be said that they are far from being an ordinary way of describing the growth of a child to manhood; there is not the slightest attempt to account for the Great Person Who, in so short a time, left such an impression on the world; there is not even an attempt to account for His great knowledge and divine self-consciousness either of His public life or His twelfth year. Whence came this knowledge and self-consciousness? One should be able to account for it if Christ was merely human. How is it that Luke does not tell us that Jesus received his knowledge under the guidance of some great philosopher? In this regard Luke is not silent concerning other men about whom he wrote; for example, about the wise Joseph, who from being a slave became the governor of all Egypt; “and (God) gave him favor and wisdom in the sight of Pharao,” Acts vii. 10; about the great Lawgiver, Moses, “and Moses was instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians” (Acts vii. 22); about Paul the orator and apostle to the Gentiles, “brought up in this City, at the feet of Gamaliel, taught according to the truth of the law of the fathers,” Acts xxii. 3. Christ is never mentioned as having received instructions at the feet of any Gamaliel; it is not mentioned in the Gospels that He even went to any school.

The Synoptics seem to imply that Christ did not receive His great knowledge in any school. They tell us that the people of the town “where He was brought up” could not account for His wisdom, Mtt. xiii. 54; Mk. vi. 2, 3; Lk. iv. 22; . . . In all tradition there is not the slightest implication that Jesus learned from any human being; the Apocryphal Gospels contain curious stories about His being brought to school, but they always make it clear that on the first day He knew more than His teacher. St. Thomas holds that Christ’s human knowledge came by discovery, not by teaching, for he writes, “it was more fitting for Christ to possess a knowledge acquired by discovery than by teaching” (Summa, Part III. Q. ix, Art. 4 ad i), and in Q. xii. art. 3, he shows that Christ did not learn anything from men.

As has previously been stated, there probably existed at the time of Our Lord, a primary school at Nazareth; Edersheim and others say that Jesus probably attended it. There is not the slightest reference to this in historical documents, which rather create a presumption against this view. But whatever view one may take of this matter, it is certain that Jesus did not attend any higher school. All evidence shows that He “never studied at any of the scribal colleges.” It is important to note that Christ, who afterwards (v.g. Matthew xix. 1-12; Luke xx. 20-47) showed His superiority over those trained in rabbinical discussion, who as a Boy of twelve in the midst of the Doctors astounded all by His understanding and His answers, did not receive any rabbinical education; He did not live in a theological atmosphere; He was not an inhabitant of the land famed for its Rabbis, Judea, nor of Jerusalem, the City of the Chief Priests and Doctors. He belonged to Galilee, a by-word among the Southerners for ignorance and uncouthness (cf. John vii. 52), and was a citizen of the town of Nazareth, from which nothing good was expected (John i. 46).

St. Luke preserves a strange and significant silence, recording only the facts; but these facts exclude any natural explanation, for the Evangelist represents Christ as having exceptional knowledge and self-consciousness, not only in His thirtieth year, but also in His twelfth, and records that as a Child He was filled with (or kept full or being filled with) wisdom, and that the grace of God was in Him. There was no time or room for natural causes to produce naturally an effect in Him. St. Luke gives no explanation; he does not state any cause for or record any origin of Christ’s knowledge and self-consciousness. The argument of silence is of value here, the silence is highly significant; it implies that the origin of Christ’s knowledge and selfconsciousness is to be sought in Christ’s own origin and nature, which had previously been described by the Evangelist.

ST. PAUL, JESUS, AND THE KENOSIS (“EMPTYING”)

St. Paul implies that Christ was always conscious of His Divinity and Divine Sonship, teaching as he does that He preexisted. Thus he writes to Timothy that “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (1 Tim. i. 15), and in other places he speaks of God sending His Son in the likeness of flesh (Rom. viii. 3; Gal. iv. 4). This doctrine is taught more clearly in 2 Cor. viii. 9, where the Apostle says that Christ who was rich became poor for men’s sake, and most clearly in Philip ii. 5-8, where St. Paul expressly states that Christ preexisted “in the form of God” and “considered it no injustice to be equal to God.” The doctrine of preexistence and Divine self-consciousness is clearly expressed here.

The Apostle (in this last mentioned passage) goes on to say that Christ “emptied Himself, taking the form of a servant, being made to the likeness of man.” This expression would not require the meaning that Jesus emptied Himself of His Divine self-consciousness. St. Paul is merely referring to Christ’s assuming human nature and does not touch the question of Jesus’ knowledge of Himself; that this is so is seen from another place where he says that in Christ are “all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” (Col. ii. 3). The Pauline references to Christ’s self-humiliation, to His taking the form of man, to His assuming the likeness of sinful flesh, do not include Christ’s knowledge and self-consciousness.

WHAT DID JESUS KNOW IN HIS CHILDHOOD AND BY AGE TWELVE?

The theories widely held in the non-Catholic world of a gradual and as it were natural development of Christ’s self-consciousness, of the awakening of His Messianic consciousness at the baptism, of doubts and crises in His self-consciousness that existed even during the Public Life, these views are entirely excluded by the Gospel text. At least according to Luke ii. 49, Christ at the age of twelve was fully aware of His real Divine Sonship. His expression of this fact is made with such calmness and indeed emphasis that there is left no ground or basis for any view that His self-consciousness was then awakening. Jesus was fully self-consciousness then, and there are no signs or hints in His saying or in any text of the Scripture of any dawning consciousness or of any time when His self-consciousness of Divine Sonship was wanting to Him. The inspired records thus imply, what is handed down in tradition, that there never was a moment when Christ did not know exactly the nature of His filial relation to God.

Tradition has it that Christ’s knowledge had its source and principle in the Hypostatic Union and dated from the first moment of this Union, i.e.. His conception. Owen (Comment, on Gospel of Luke, 44) had already argued with force against Olshausen’s theory of a gradual development of Christ’s consciousness. See the able statement of Dalman: Words of J., 286. Du Bose says, “There was never a time in the history of His consciousness when His divinity was wholly latent or lay completely beneath the activities of His human mind.” (The Consciousness of Jesus, 29.)

Christ’s self-consciousness or, to speak more correctly, His own testimony to Himself, is one of the chief supports of the belief in His Divinity — the other being the performance of miracles in confirmation of what He said. Hence for this question also the words of the Boy Jesus are important.

[Those wishing to do further research on this question will want to consult the very extensive bibliography that the author offers. Some of the books mentioned may be fully accessible in Google Books, since the date from 1922 and earlier]