Dialogue with a Calvinist

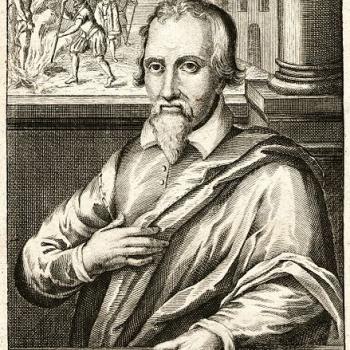

Michael Servetus (1511-1553): non-trinitarian heretic whom John Calvin had burned at the stake [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

This discussion occurred in a combox on the Reformed Protestant-dominated Green Baggins website. See Jeff Cagle’s entire comment #268 regarding Luther’s excommunication. His words below will be in blue.* * * * *

I threw #33 in as an aside: we note that even the pope errs here in his judgment that “burning heretics is against the will of the Spirit” is an error.

*

Every heretic who is damned in the end will be burned with the express consent of the Holy Spirit for eternity, no? Calvinists (unlike Catholics and Arminians and Wesleyans and Orthodox) even assert that this was decreed by God from eternity before the damned person had any say in the matter at all. So I wouldn’t be so quick to make this point.

*

The issue (pondered beyond mere provocation and polemics and a “gotcha” mentality) is how heresy is to be dealt with and/or punished in this life also. The medievals thought that danger to souls was at least as dangerous and harmful to society as danger to their physical bodies or emotional well-being. They have a certain point.

I am a passionate believer in complete religious tolerance, and the Catholic Church has taken that course in Vatican II. We all pretty much agree on that now. If we wish to go back to the previous time and those practices, then all I ask is that we also condemn the many Protestant excesses as well, as I argued above in my comments on the Inquisition.

*

*

I unequivocally repudiate the practices of hanging witches, and of drowning Anabaptists, and so on. I can do so with the understanding that my Protestant forbears erred in understanding the applicability of OT law to NT times.

But on what grounds can you repudiate the practice of the Inquisition? Or of Leo X’s comment above? Would that not be an instance in which the Church erred in a matter of doctrine? . . .

I appears to me that the Church has always thought of herself as standing in the apostolic tradition; and certainly the burning of heretics was considered to be within that tradition also.

*

The Inquisition was not a doctrine in the first place; it was a practice: a particular way of approaching the question of heresy and corrupters of souls, as it were. Secular society today is engaging in the same debate when it tries to figure out how to deal with captured terrorists. The first Protestants almost all agreed with this method, then in due course all Christians have forsaken it as unworkable and too potentially dangerous in its power elements (except for the reconstructionists in your camp — not mine — who would like to bring it back).

*

I would argue that no absolute scriptural argument can be made against it. This is why it can change, and why it can’t be condemned through and through as utterly evil. Most Christians agree that war is sometimes justifiable. Most of us accept the notion of police power (killing a guy who is holding a little girl hostage, etc.). We put people to death for committing crimes against persons’ bodies; are not their souls far more valuable?

Therefore, one can make an argument that capital punishment for heresy is entirely just and good for society. St. Thomas Aquinas (Calvinists’ second favorite Catholic after St. Augustine) did so. In the Middle Ages, this was the consensus, because they valued spiritual things and the soul far more than we do today. To them, theology truly meant something and affected all of life, whereas today we compartmentalize everything (including faith and religion) in neat little boxes.

It is easily shown to be a “biblical” practice in the wars of Israel against her enemies, commanded by God (often complete with mass executions), and in the various grounds for capital punishment under the law (e.g., I believe idolatry — a religious belief — was one of those).

*

It is also indicated in its essentials in the NT (lest I get the reply that I only mentioned OT stuff). For example:

Acts 5:1-12 (RSV) But a man named Anani’as with his wife Sapphi’ra sold a piece of property, [2] and with his wife’s knowledge he kept back some of the proceeds, and brought only a part and laid it at the apostles’ feet. [3] But Peter said, “Anani’as, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit and to keep back part of the proceeds of the land? [4] While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, was it not at your disposal? How is it that you have contrived this deed in your heart? You have not lied to men but to God.” [5] When Anani’as heard these words, he fell down and died. And great fear came upon all who heard of it. [6] The young men rose and wrapped him up and carried him out and buried him. [7] After an interval of about three hours his wife came in, not knowing what had happened. [8] And Peter said to her, “Tell me whether you sold the land for so much.” And she said, “Yes, for so much.” [9] But Peter said to her, “How is it that you have agreed together to tempt the Spirit of the Lord? Hark, the feet of those that have buried your husband are at the door, and they will carry you out.” [10] Immediately she fell down at his feet and died. When the young men came in they found her dead, and they carried her out and buried her beside her husband. [11] And great fear came upon the whole church, and upon all who heard of these things. [12] Now many signs and wonders were done among the people by the hands of the apostles. And they were all together in Solomon’s Portico.

Peter presides over what is ultimately God’s judgment. God struck them dead for sin. It’s capital punishment for sin. Peter didn’t say to them, “let he who is without sin cast the first stone,” and send them on their way. We see, then, the notion of capital punishment for a spiritual matter: “lying to God”. Therefore, the underlying principle of the Inquisition is seen in the NT and in the New Covenant.

One might argue that the same sort of sanctioned corporal, capital punishment is at least suggested also in the hideous deaths of Judas and Herod. It ain’t just OT stuff.

This are of thought is similar to Christian thought on just war (with the Catholic Church taking the lead, as usual in today’s moral issues). Peace is thought to be the best way to go, if at all possible. Today, tolerance in matters of religious faith is thought to be the best approach. But it was not always so. And those who thought differently had some biblical warrant.

One reason why I point out the special hypocrisy of Luther and Calvin drowning Anabaptists is because it proceeded on a different principle: Luther had established Bible Alone as the Rule of Faith and plain Scripture as understood by the common man without any necessary authoritative Church or Tradition, yet as soon as anyone came up with a different conclusion than his, he wanted to kill them. Anabaptists were no different from Baptists today. I have noted many times that a Reformed Baptist like James White could have been killed in Lutheran or Calvinist circles, but I as a Catholic almost always would not have been.

Thus, Luther and Calvin were persecuting fellow Protestants who simply differed from them on matters now regarded usually as relative trivialities in Protestant circles. The Anabaptists were applying Luther’s own principle of authority. The Inquisition, on the other hand, often (and initially) was dealing with extraordinary heresies like the Albigensians and Cathari, who were species of revived Gnosticism and in no way, shape, or form Christian.

*****

Meta Description: The medieval worldview made arguments for putting heretics to death. We disagree, but we can seek to understand their sincere views.

*

Meta Keywords: Inquisition, crusades, religious tolerance, religious persecution, capital punishment, death penalty, death penalty for heresy, heresy, heretics