***

***

I. Introduction and Statement of Purpose

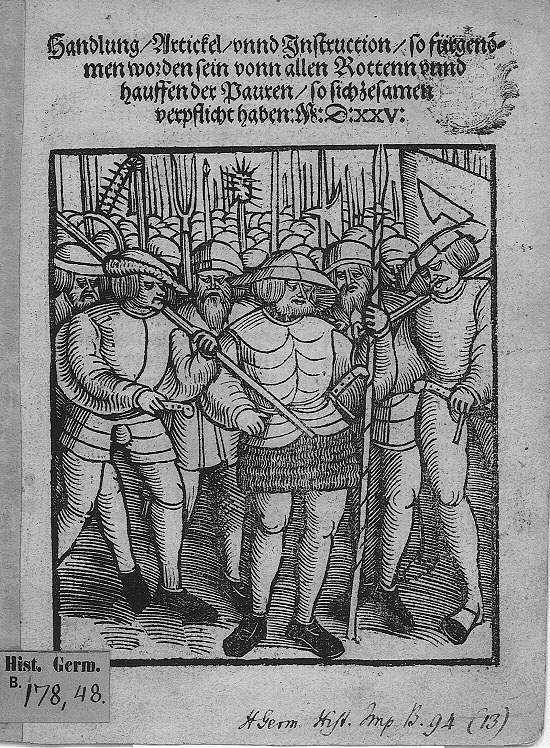

Historians on both sides are in agreement that Luther never supported the Peasants’ Revolt (or insurrection in general). Many, however (including Roland Bainton, the famous Protestant author of the biography Here I Stand), believe that he used highly intemperate language that couldn’t help but be misinterpreted in the worst possible sense by the peasants. I agree with these Protestant scholars, and this has been my stated position in writing for twelve years now (I initially formed the opinion in 1991 as a result of reading Hartmann Grisar, the Catholic historian who is supposedly so “anti-Luther”).

No Catholic (or Protestant) historian I have found — not even Janssen — asserts that Luther deliberately wanted to cause the Peasants’ Revolt, or that he was the primary cause of it. Quite the contrary . . . My long-held position on this agrees, therefore, with the consensus opinion of historians of all stripes. I think Luther had the typical naivete of many sincerely, deeply-committed and (what might be called) “super-pious” religious people. It is also undeniably true that Luther’s thought is highly complex, nuanced, sometimes vacillating or seemingly or actually self-contradictory, and often difficult to understand.

Thus, for him to say the sort of extreme (seemingly straightforward) things that he said, have such opinions distributed by the tens of thousands in pamphlets, and to expect everyone (even uneducated peasants) to understand the proper sense and take into consideration context and so forth, is highly unreasonable and irresponsible. I should like to quote some reputable Protestant or secularist historians in this regard, with whom I wholeheartedly agree:

Roland Bainton: “A movement so religiously minded could not but be affected by the Reformation . . . Luther certainly had blasted usury . . . His attitude on monasticism likewise admirably suited peasant covetousness for the spoliation of cloisters. The peasants with good reason felt themselves strongly drawn to Luther . . . a complete dissociation of the reform from the Peasants’ War is not defensible.”

Gordon Rupp: “Luther had indeed laid himself open to misrepresentation.”

Owen Chadwick: “his simple and enclosed upbringing prevented him from realizing the effect of violent language upon simple minds. Luther, not an extremist, often sounded like an extremist.”

Will Durant: “Luther, the preachers, and the pamphleteers were not the cause of the revolt; . . . But it could be argued that the gospel of Luther and his more radical followers “poured oil on the flames,” and turned the resentment of the oppressed into utopian delusions, uncalculated violence, and passionate revenge . . . The peasants had a case against him. He had not only predicted social revolution, he had said he would not be displeased by it . . . He had made no protest against the secular appropriation of ecclesiastical property.”

H.G. Koenigsberger: “Only someone of Luther’s own naive singleness of mind could imagine that his inflammatory attacks on one of the great pillars of the established order would not be interpreted as an attack on the whole social order, or on that part of it which it suited different interests, from princes to peasants, to attack.”

James Mackinnon: “To threaten the princes with the wrath of God was all very well, but such a threat would have no effect in remedying the peasants’ grievances, and they might well argue that God had chosen them, as he practically admitted, to be the effective agents of His wrath.”

Preserved Smith: “Luther, indeed, could honestly say that he had consistently preached the duty of obedience and the wickedness of sedition, nevertheless his democratic message of the brotherhood of man . . . worked in many ways undreamt of by himself. Moreover, he had mightily championed the cause of the oppressed commoner against his masters. ‘The people neither can nor will endure your tyranny any longer,’ said he to the nobles; . . .”

Luther believed that the papacy and the entire edifice of institutional Catholicism would come to an end, not by an insurrection or rebellion, but by a direct intervention of God Himself (in fact, by nothing less than the Second Coming, as he states more than once). In 1521 and 1522 he was caught up into and (arguably) obsessed by an apocalyptic vision of what was about to happen, in God’s providence. This being the case, at first he didn’t feel it was necessary to oppose even those who threatened a rebellion (later he changed his mind, when the resulting societal chaos required swift action). Thus he wrote in December, 1521 (source information below):

The spiritual estate will not be destroyed by the hand of man, nor by insurrection. Their wickedness is so horrible that nothing but a direct manifestation of the wrath of God itself, without any intermediary whatever, will be punishment sufficient for them. And therefore I have never yet let men persuade me to oppose those who threaten to use hands and flails. I know quite well that they will get no chance to do so. They may, indeed, use violence against some, but there will be no general use made of violence . . . it will not come to violence, and there is therefore no need that I restrain men’s hands . . .

The relationship between this divine wrath and judgment and those whom God uses to execute it, however, remains somewhat obscure, unclear, and ambiguous in Luther’s writings. Perhaps the key to this conundrum is found in a remarkable statement he made in a private letter, dated 4 May 1525: “If God permits the peasants to extirpate the princes to fulfil his wrath, he will give them hell fire for it as a reward.”

So, while Luther opposed insurrection on principle, there is a tension in his seemingly contradictory utterances between opposition to the populace taking up arms against spiritual and political tyranny, and a deluded confidence and at times almost gleeful wish that apocalyptic judgment was soon to occur, regardless of the means God used to bring it about (one recalls the ancient Babylonians, whom God used to judge the Hebrews). This produces an odd combination of sincere disclaimers against advocating violence, accompanied by (often in the same piece of writing) thinly-veiled quasi-threats and quasi-prophetic judgments upon the powers of the time, sternly warning of the impending Apocalypse and destruction of the “Romish Sodom” and all its pomps, pretenses, corruptions, and vices.

On a more earthly, mundane, practical plane, however, it is astonishing to note how cavalierlry Luther sanctions wholesale theft of ecclesiastical properties (see proofs of this in the passages listed under 12 December 1522 and Spring 1523), on the grounds that the inhabitants had forsaken the “gospel” (as he — quite conveniently in this case — defined it, of course). This was to be a hallmark of the “Reformation” in Germany and also in England and Scandinavia, and was justified as a matter of “conscience” by the Protestants at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, who flatly refused to return stolen properties, as a gesture of good will and reconciliation with the Catholics (see the section on the Diet of Augsburg in my review of the movie Luther). Luther was still rationalizing this outrageous and unjust criminal theft in 1541:

If they are not the church but the devil’s whore that has not remained faithful to Christ, then it is irrefutably and thoroughly established that they should not possess church property.(Wider Hans Wurst, or Against Jack Sausage, LW, vol. 41, 179-256, translated by Eric W. Gritsch; citation from p. 220)

But back to our more immediate subject: Generally speaking, Luther had a problem with his tongue. And the social repercussions were massive and tragic. The Bible speaks a lot about an unbridled tongue. It is no small sin at all. How German peasants (Luther was of rural peasant stock) may have habitually expressed themselves in the 16th century might be an interesting historical tidbit, but it has no bearing on Christian ethics, where the tongue and slander and causing uproar and divisions are concerned. One doesn’t “get off” in God’s eyes for real sins because of cultural context. It is all the more serious when such remarks are arguably a major cause in both provoking and violently quelling a rebellion in which some 130,000 human beings lost their lives: almost all violently and cruelly.

Luther might indeed mean one thing when he utters his impassioned hyper-polemical, quasi-prophetic jeremiads (I have no problem with that), but he was (by the looks of it) so naive and lacking in practical wisdom about human nature and human affairs (“worldly” or “real-life” considerations) that he apparently had no idea what harm and ill consequences his words might cause. I agree that this gets him “off the hook” to some extent (I certainly freely grant him his good intentions and sincerity), but not all that much, in my opinion. I still think he bears much responsibility for the resulting extent of the sad division by virtue of his constant polemics (often involving much lying about the Catholic Church).

Furthermore, he seemed to be absolutely naive as to how his own principles would be interpreted, extended, and applied by others. He asserted a more or less absolute primacy of private judgment and conscience at the Diet of Worms in 1521 (“unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason . . ., ” etc.). But four years later (precisely because of the fruit and implications of the Peasants’ Revolt) he renounced this — for all practical intents and purposes — and adopted the largely caesaropapist State Church model where secular princes decided what whole regions had to believe (rather than individuals).

The Anabaptists had gone on to apply his initial principle more consistently than he himself. They advocated non-violence and toleration, whereas the Lutherans and Calvinists and Zwinglians tortured, drowned, and otherwise murdered these fellow Protestants by the thousands (persecution and capital punishment of the Anabaptists was adopted in 1529 at the Diet of Speyer — where the term “Protestant” originated — with Luther’s consent). Luther’s support of a notion that earlier he had believed was wicked, unbiblical, and held only by non-Christians, was further reiterated in his Commentary on the 82nd Psalm and in a 1536 pamphlet.

I have contended for a dozen years that Luther’s philosophical, epistemological, and socio-political naivete and shortsightedness made him blind to the predictable, probable results of his rhetoric (both angry and calmly theological). So when other groups like the Anabaptists and the Zwinglians differed from him on baptism and the Eucharist (using his own principles of private judgment in so doing), Luther thought this was ineffably scandalous and inexcusable — never noting the irony that it was no less (in fact, much more) absurd or unwarranted for fellow Protestants to disagree with him (as simply one self-anointed man who claimed to be speaking only for God) than it was for he himself to dissent from longstanding Catholic tradition. To then advocate the death penalty for such “dissidents” was highly ironic and odd (to put it mildly), given his earlier ethical positions on the use of force.

Things like these are what continue to fascinate me about Luther. He was an undeniably courageous man and a passionately-committed Christian, but he was also a greatly-flawed man, and such persons often cause much harm in society, to the extent that they are culturally influential (as Luther obviously was). Since the myths and lionization of Luther as the Great Super-Hero and Slayer of Corrupt Catholicism/Babylon and Restorer of the Bible and the Gospel from Romish Darkness persist, I take it as part of my duty to explore and make more known other lesser-known aspects of the man (and of the Catholic Church that he so slandered and falsely portrayed), so people will get the whole picture, and not a tremendously one-sided, slanted one.

My purpose is not (at all) to demonize Luther or make him out to be bad, evil, or the devil incarnate, but only to present a fuller historical picture (whatever the truth is: “positive” or “negative”) and to make some criticisms where I think they are warranted (with the background support of historians on all sides). This doesn’t amount to equating Luther with Attila the Hun, Vlad the Impaler, or Joseph Stalin; it is simply viewing him as a fallen, flawed man, as all of us are. He shouldn’t “get a pass” simply because he opposed the Catholic Church: the thing that so many people detest and loathe.

Nor does every Catholic criticism of Luther or early or later Protestantism amount to deliberate slander, with a propagandistic, “I must always make my own side come off looking righteous and saintly, at all costs” intent. There is such a thing as legitimate historiography and reasonable opinions drawn therefrom. And (thankfully) such scholarship can (and very often does, at least on a scholarly level) unite Protestants and Catholics where it concerns certain verified facts. I write as a mere lay apologist and non-scholar, but I enlist reputable historians and copious quotations from Luther himself in order to arrive at my conclusions, both “positive” and “negative” — as the case may be (just as the professional historians do).

Blue = statements of Luther indicating his fundamental opposition to insurrection of the non-governmental masses and resort to physical violence for spiritual or ecclesiastical ends and goals

Green = statements by historians having a particular relevance to the question at hand: the relationship between Luther’s rhetoric (and also theology, to a lesser extent) and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1524-1525

Affiliations of historians will be noted where known (with question marks in cases where affiliation is suspected but not known for sure):

P = Protestant

C = Catholic

S = Secular

Citations will simply refer to the author of books in the bibliography, and page number. Whatever doesn’t appear there will be fully-documented after the quote itself.

II. Luther’s Own Words, in Chronological Order

FEBRUARY 1520

If you understand the Gospel rightly, I beseech you not to believe that it can be carried on without tumult, scandal, sedition . . . The word of God is a sword, is war, is ruin, is scandal . . .

(O’Connor, 41; LL, I, 417; Letter to Georg Spalatin)

I have an idea that a revolution is about to take place unless God withhold Satan . . . The Word of God can never be advanced without whirlwind, tumult, and danger . . . One must either despair of peace and tranquillity or else deny the Word. War is of the Lord who did not come to send peace. Take care not to hope that the cause of Christ can be advanced in the world peacefully and sweetly, since you see the battle has been waged with his own blood and that of the martyrs.

(Smith, 72; same letter to Georg Spalatin)

(Bainton, 115; Carroll, 1; WA, VI, 347; EA, II, 107; PE, IV, 203; in reply to arguments of the Dominican Sylvester Prierias, Master of the Sacred Palace at Rome; On the Pope as an Infallible Teacher, or On the Papacy at Rome. Schaff gives its Latin title as De juridica et irrefragabili veritate Romanae Ecclesiae Romanique Pontificis)

***

(Durant, 351; from WA, VIII, 203)

***

30 JULY 1520

I expound my philosophy without slaughter and blood.

(Smith, 77; letter to Gerard Listrius at Zwolle, from Wittenberg)

***

(Smith, 86; letter to John Lang at Erfurt, from Wittenberg)

***

(Schaff, VII, § 46, “Christian Freedom — Luther’s Last Letter to the Pope”; Letter to Pope Leo X)

***

“You are frightening away from you your supporters by your constant reference to troops and arms. We can easily enough throw everything into confusion, but it will not be in our power, believe me, to restore things to peace and order.”

JANUARY 1521

All the strife and the wars of the Old Testament prefigured the preaching of the Gospel which must produce strife, dissension, disputes, disturbance. Such was the condition of Christendom when it was at its best, in the times of the apostles and martyrs.

That is a blessed dissension, disturbance, and commotion which is produced by the Word of God; it is the beginning of true faith and of war against false faith; it is the coming again of the days of suffering and persecution and the right condition of Christendom.

(Reply to the Answer of the Leipzig Goat [Jerome Emser], PE, III, 287-305, translated by A. Steimle; citation from p. 303)

***

***

(PE, III, 204, translated by W.A. Lambert; LL, I, 543; Letter to Georg Spalatin)

***

(Grisar [1], 172; Wider die Bulle des Endchrists; / Assertion of All the Articles Condemned by the Last Bull of Antichrist; WA, VI, 614 ff.; EA, XXIV-2, 38 ff.)

***

(Bainton, 115; from WA, VII, 645-646)

***

But tell me, dear Emser, since you dare to put it down on paper that it is right and necessary to burn heretics and think that this does not soil your hands with Christian blood, why should it not also be right to take you, Sylvester, the pope, and all your adherents and put you to a most shameful death? Since you dare to publish a doctrine that is not only heretical but antichristian, which all the devils would not venture to utter — that the Gospel must be confirmed by the pope, that its authority is bound up with the pope’s authority, and that what is done by the pope is done by the church. What heretic has ever thus at one stroke condemned and destroyed God’s Word? Therefore I still declare and maintain that, if heretics deserve the stake, you and the pope ought to be put to death a thousand times. But I would not have it done. Your judge is not far off, He will find you without fail and without delay.

. . . what would become of the papacy . . . ? Christ Himself must abolish it by coming with the final judgment; nothing else will avail.

(Dr. Martin Luther’s Answer to the Superchristian, Superspiritual, and Superlearned Book of Goat Emser of Leipzig, With a Glance at His Comrade Murner, PE, III, 307-401, translated by A. Steimle; citations from 343-344, 366)

***

‘Swine and asses are able to see how stubbornly they act . . . What if my death should prove a disaster to you all? God is not to be trifled with.’ ”

(Grisar [1], 193; EA, Br. III, 153)

(Smith, 122; letter to Georg Spalatin at Worms from the Wartburg)

***

Now, I am not at all displeased to hear that the clergy are brought to such a state of fear and anxiety. perhaps they will come to their senses and moderate their mad tyranny. Would to God their terror and fear were even greater. But I feel quite confident, and have no fear whatever that there will be an insurrection, at least one that would be general and affect all the clergy . . .

. . . any man who can and will may threaten and frighten them, that the Scriptures may be fulfilled, which say of such evil doers, in Psalm xxxvi, “Their iniquity is made manifest that men may hate them” . . .

According to the Scriptures such fear and anxiety come upon the enemies of God as the beginning of their destruction. Therefore it is right, and pleases me well, that this punishment is beginning to be felt by the papists who persecute and condemn the divine truth. They shall soon suffer more keenly . . . Already an unspeakable severity and anger without limit has begun to break upon them. The heaven is iron, the earth is brass. No prayers can save them now. Wrath, as Paul says of the Jews,is come upon them to the uttermost. God’s purposes demand far more than an insurrection. As a whole they are beyond the reach of help . . . The Scriptures have foretold for the pope and his followers an end far worse than bodily death and insurrection . . .

These texts [having cited Dan 8:25, 2 Thess 2:8, Is 11:4, Ps 10:15] teach us how both the pope and his antichristian government shall be destroyed . . .

If once the truth is recognized and made known, pope, priests, monks, and the whole papacy will end in shame and disgrace . . .

. . . these texts [2 Thess 2:8, 1 Thess 5:3] have made me certain that the papacy and the spiritual estate will not be destroyed by the hand of man, nor by insurrection. Their wickedness is so horrible that nothing but a direct manifestation of the wrath of God itself, without any intermediary whatever, will be punishment sufficient for them. And therefore I have never yet let men persuade me to oppose those who threaten to use hands and flails. I know quite well that they will get no chance to do so. They may, indeed, use violence against some, but there will be no general use made of violence . . .

. . . it will not come to violence, and there is therefore no need that I restrain men’s hands . . . what is done by constituted authority cannot be regarded as rebellion . . . But the mind of the common man we must calm, and tell him to give way not even to the passions and words which lead to insurrection, and to do nothing at all unless commanded to do so by his superiors or assured of the co-operation of the authorities . . . there will be no real violence. All that men are saying and thinking on the subject amounts to nothing more than wasted words and idle thoughts . . .

. . . princes and nobles . . . ought to do their part, oppose the evil with all the power of their sword, in the hope that they might turn aside and moderate at least some of the wrath of God, as Moses did according to Exodus xxxii . . . I do not mean that the priests ought to be killed, for that is not necessary, but that whatever they do beyond and contrary to the Gospel should be forbidden by commands properly enforced. Words and edicts will more than suffice in dealing with them; there is no need of more material weapons.

. . . insurrection is an unprofitable method of procedure, and never results in the desired reformation. For insurrection is devoid of reason and generally hurts the innocent more than the guilty. Hence no insurrection is ever right, no matter how good the cause in whose interest it is made. The harm resulting from it always exceeds the amount of reformation accomplished.

. . . My sympathies are and always will be with those against whom insurrection is made, however wrong the cause they stand for . . . God has forbidden insurrection . . . insurrection is nothing else than being one’s own judge and avenger, and that God cannot endure . . . God will have nothing to do with it . . .

. . . the devil . . . wants to stir up an insurrection through those who glory in the Gospel, and hopes in this way to bring our teaching into contempt, as if the devil and not God were its author. Some men are already making much of this interpretation in their preaching, as a result of the attack on the priests which the devil inspired at Erfurt . . . Those who read and understand my teaching correctly will not make an insurrection. They have not so learned from me . . .

. . . we must slay him [“the pope and his papists”] with words; the mouth of Christ must do it . . . This will do more good than a hundred insurrections. Our violence will do him no harm at all, but rather make him stronger, as many have experienced before now . . .

Therefore you need not desire an armed insurrection. Christ has Himself already begun an insurrection with His mouth which will be more than the pope can bear . . .

(An Earnest Exhortation for all Christians, Warning Them Against Insurrection and Rebellion, PE, III, 201-222, translated by W.A. Lambert, citations from pp. 206-213, 215-216; also in LW, vol. 45, 57-74 [revised translation by Walther I. Brandt]; WA, VIII, 676-687, EA, XXII, 44-59; )

1522

Some . . . will not treat our gospel rightly; but have we not gibbets, wheels, swords, and knives? Those who are obdurate can be brought to reason.

(Janssen, III, 266)

The spiritual powers . . . also the temporal ones, will have to succumb to the Gospel, either through love or through force, as is clearly proved by all Biblical history.

(Janssen, III, 267; Letter to Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony)

***

***

***

(Smith, 145; letter to Frederick, Elector of Saxony, at Lochau)

(LW, vol. 45, 58; also WA, Br. 2, 461, 469; letter to Frederick, Elector of Saxony)

***

(Schaff, VII, § 68, “Luther Restores Order in Wittenberg,” second of eight sermons preached upon his return from the Wartburg; also in a different translation in Smith, 148; the sermons appear in PE, II, 395 ff.)

***

(Smith, 149; letter to Nicholas Hausmann at Zwickau, from Wittenberg)

***

(LW, vol. 45, 58; also WA, Br. 2, 479; letter to Wenceslaus Link)

We are triumphing over the papal tyranny, which formerly crushed kings and princes; how much more easily, then, shall we not overcome and trample down the princes themselves!

(Durant, 378 / Janssen, III, 268; Letter to Wenzel Link — presumably the same as the one above)

4 JULY 1522

. . . Thus we should punish bishops and spiritual dominion harder and more severely than worldly dominion for two reasons: first, because this spiritual dominion does not derive from God, for God does not know these masked people and St. Nicholas bishops, because they neither teach nor perform any episcopal duties. Nor did they derive from men. They have imposed themselves on others and placed themselves into this rule against God and men, as is the custom of tyrants who rule only out of God’s wrath. Worldly dominion derives from God’s gracious order to suppress the evil and protect the godly, Romans 13[:4] . Second, worldly rule, even though it commits violence and injustice, hurts only the body and property. But spiritual dominion, whenever it is unholy and does not support God’s word, is like a wolf and murderer of the soul, and it is just as though the devil himself were ruling there. That is why one should beware as much of the bishop who does not teach God’s word as of the devil himself. For wherever God’s word is missing, there we certainly find only the devil’s teaching and the murder of souls. For without God’s word the soul can neither live nor be delivered from the devil.

But if they say that one should beware of rebelling against spiritual authority, I answer: Should God’s word be dispensed with and the whole world perish? Is it right that all souls should be killed eternally so that the temporal show of these masks is left in peace? It would be better to kill all bishops and to annihilate all religious foundations and monasteries than to let a single soul perish, not to mention losing all souls for the sake of these useless dummies and idols. What good are they, except to live in lust from the sweat and labor of others and to impede the word of God? They are afraid of physical rebellion and do not care about spiritual destruction. Are they not intelligent, honest people! If they accepted God’s word and sought the life of the soul, God would be with them, since he is a God of peace. Then there would be no fear of rebellion. But if they refuse to hear God’s word and rather rage and rave with banning, burning, killing, and all evil, what could be better for them than to encounter a strong rebellion which exterminates them from the world? One could only laugh if it did happen, as the divine wisdom says, Proverbs 1[:25–27], “You have hated my punishment and misused my teaching; therefore I will laugh at your calamity and I will mock you when disaster strikes you.”

Not God’s word but stubborn disobedience [to God’s word] creates rebellion. Whoever rebels against it shall get his due reward. Whoever accepts God’s word does not start unrest, although he is no longer afraid of the masks and does not worship the dummies.

(Against the Spiritual Estate of the Pope and the Bishops Falsely So-Called; LW, vol. 39, 239-299; translated by Eric W. and Ruth C. Gritsch. Quotation from pp. 252-253; WA, vol. 28, 142-201)

12 DECEMBER 1522

Grisar [1] (228): “Count Johann Heinrich of Schwarzburg became the founder of Lutheranism in his territories in virtue of a decree authorized by Luther . . . Luther replied on December 12, 1522 that Count Gunther had naturally expected the monks to preach the Gospel, but if witnesses could testify that they did not preach the true Gospel (of Luther), but papistical heresies, the count would have the right, nay, the duty, to oust them from their parishes.”

For it is not unlawful, indeed, it is absolutely right to drive the wolf from the sheepfold . . . A preacher is not given property and tithes in order that he should do injury, but that he should labor profitably. If he does not work to the advantage of the people, the endowments are his no longer.

1523

All those who work toward this end and who risk body, property, and honor that the bishoprics may be destroyed and the episcopal government rooted out are God’s dear children and true Christians. They keep God’s commandment and fight against the devil’s order. Or, if they cannot do this, at least they condemn and avoid such a government. On the other hand, all those who obey the government of the bishops and subject themselves to it in willing obedience are the devil’s own servants and fight against God’s order and law . . .

Here you stand against St. Paul, against the Holy Spirit; and the Holy Spirit stands against you. What will you say now? Or have you become dumb? Here you have your verdict: all the world must destroy you and your government. Whoever stands on your side falls under God’s disfavor; whoever destroys you stands in God’s favor.

By no means do I want such destruction and extinction to be understood in the sense of using the fist and the sword, for they are not worthy of such punishment—and nothing is achieved in this way. Rather, as Daniel 8[:25] teaches, “by no human hand” shall the Antichrist be destroyed. Everyone should speak, teach, and stand against him with God’s word until he is put to shame and collapses, completely alone and even despising himself. This is true Christian destruction and every effort should be made to this end . . .

If someone said to me at this point, “Previously you have rejected the pope; will you now also reject bishops and the spiritual estate? Is everything to be turned around?” my answer would be: Judge for yourself and decide whether I turn things around by preferring divine word and order, or whether they turn things around by preferring their order and destroying God’s . . . Nobody should look at that which opposes God’s word, nor should one care what the consequences may or may not be. Instead, one should look at God’s word alone and not worry — even if angels were involved — about who will get hurt, what will happen, or what the result will be . . .

. . . Christ, Peter, Paul, and the prophets proclaimed that there would be no greater disaster on earth than the advent of the Antichrist and of the final evil . . .

Since it is clear, then . . . that the bishops are not only masks and idols but also an accursed people before God — rising up against God’s order to destroy the gospel and ruin souls — every Christian should help with his body and property to put an end to their tyranny. One should cheerfully do everything possible against them, just as though they were the devil himself. One should trample obedience to them just as though it were obedience to the devil; . . .

(Doctor Luther’s Bull and Reformation, LW, vol. 39, 278-283; translated by Eric W. and Ruth C. Gritsch. Published in LW as part of Against the Spiritual Estate of the Pope and the Bishops Falsely So-Called; but originally published separately in two special editions in 1523, in Erfurt and Augsburg, entitled, The Bull of the Ecclesiastic in Wittenberg Against the Papal Bishops, Granting God’s Grace and Merit to All who Keep and Obey It; WA, X-11, 98-158; citations from 278-280, 283)

***

Who does not see that all bishops, foundations, monastic houses, universities, with all that are therein, rage against this clear word of Christ . . .? Hence they are certainly to be regarded as murderers, thieves, wolves and apostate Christians . . .

. . . the hearers not only have the power and the right to judge all preaching, but are obliged to judge it under penalty of forfeiting the favor of Divine Majesty. Thus we see in how unchristian a manner the despots dealt with us when they deprived us of this right and appropriated it to themselves. For this thing alone they have richly deserved to be cast out of the Christian Church and driven forth as wolves, thieves and murderers . . .

. . . where there is a Christian congregation which has the Gospel, it not only has the right and power, but is in duty bound . . . under pain of forfeiting its salvation, to shun, to flee, to put down, to withdraw from, the authority which our bishops, abbots, monastic houses, foundations, and the like exercise today . . .

(The Right and Power of a Christian Congregation or Community to Judge all Teaching and to Call, Appoint, and Dismiss Teachers, Established and Proved From Scripture, PE, IV, 75-85, translated by A.T.W. Steinhaeuser; WA, XI, 406 ff.; EA, XXII, 141 ff.; citations from 75-79)

. . . there is need of great care, lest the possessions of such vacated foundations become common plunder and everyone make off with what he can get . . . the blame is laid at my door whenever monasteries and foundations are vacated . . . This makes me unwilling to take the additional blame if some greedy bellies should grab these spiritual possessions and claim, in excuse of their conduct, that I was the cause of it . . .

In the first place: it would indeed be well if no rural monasteries, such as those of the Benedictines, Cistercians, Celestines, and the like, had ever appeared upon earth. But now that they are here, the best thing is to suffer them to pass away or to assist them, wherever one properly can, to disappear altogether. This may be done in the following ways. first, by suffering the inmates to leave, if they choose, of their own free will . . .

[then follows an exhortation to charitably provide for those who won’t or can’t leave]

I advise the temporal authorities, however, to take over the possessions of such monasteries . . . it is not a case of greed opposing the spiritual possessions, but of Christian faith opposing the monasteries . . . I am writing this for those only who understand the Gospel and who have the right to take such action in their own lands, cities and jurisdiction . . .

. . . the third way is best, namely, to devote all remaining possessions to the common fund of a common chest, out of which gifts and loans might be made, in Christian love, to all the needy in the land, whether nobles or commons . . .

I am setting down this advice in accordance with Christian love for Christians alone. We must expect greed to creep in here and there . . . it is better that greed take too much in an orderly way than that the whole thing become common plunder, as it happened in Bohemia. Let everyone examine himself to see what he should take for his own needs and what he should leave for the common chest.

In the third place: the same procedure should be followed with respect to abbacies, foundations, and chapters in control of lands, cities and other possessions. For such bishops and foundations are neither bishops nor foundations; they are really at bottom temporal lords sailing under a spiritual name . . .

In the fourth place: part of the possessions of the monasteries and foundations . . . are based upon usury, which now calls itself everywhere “interest,” and which has in but a few years swallowed up the whole world . . . God says, “I hate robbery for burnt offering.” [Is 61:8] . . .

But whosoever will not follow this advice nor curb his greed, of him I wash my hands.

(Preface to an Ordinance of a Common Chest, PE, IV, 92-98, translated by A.T.W. Steinhaeuser; WA, XII, 11-30; EA, XXII, 106-130; citations from 93-98)

*****

***

EA = Erlangen Ausgabe edition of Luther’s Works (Werke) in German, 1868, 67 volumes.

LW = Luther’s Works, American edition, edited by Jaroslav Pelikan (vols. 1-30) and Helmut T. Lehmann (vols. 31-55), St. Louis: Concordia Pub. House (vols. 1-30); Philadelphia: Fortress Press (vols. 31-55), 1955.

PE = Luther’s Works, Philadelphia edition (6 volumes), edited and translated by C.M. Jacobs and A.T.W. Steinhaeuser et al, A.J. Holman Co., The Castle Press, and Muhlenberg Press, 1932.

LL = Luther’s Letters (German), edited by M. De Wette, Berlin: 1828

Bainton, Roland (P), Here I Stand [online], New York: Mentor Books, 1950.

Carroll, Warren H. (C), The Cleaving of Christendom, Front Royal, VA: Christendom Press, 2000 (Vol. 4 of A History of Christendom).

Chadwick, Owen (P), The Reformation, New York: Penguin Books, revised edition, 1972.

Daniel-Rops, Henri (C), The Protestant Reformation, volume 2, translated Audrey Butler, Garden City, NY: Doubleday Image, 1961.

Durant, Will (S), The Reformation, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957 (volume 6 of the 10 volume work, The Story of Civilization, 1967).

Grisar, Hartmann (C) [1], Martin Luther: His Life and Work, translated from the 2nd German edition by Frank J. Eble, Westminster, MD: The Newman Press, 1950; originally 1930.

Grisar, Hartmann (C) [2], Luther [online: volumes I / II / III / IV / V / VI], translated by E.M. Lamond, edited by Luigi Cappadelta, 6 volumes, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1915.

Hughes, Philip (C), A Popular History of the Reformation, Garden City, NY: Doubleday Image,

1957.

Hurstfield, Joel (P), editor, The Reformation Crisis, New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1966.

Janssen, Johannes (C), History of the German People From the Close of the Middle Ages, 16

volumes, translated by A.M. Christie, St. Louis: B. Herder, 1910; originally 1891.

McGrath, Alister E. (P), Reformation Thought: An Introduction, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 2nd edition, 1993.

O’Connor, Henry (C), Luther’s Own Statements, New York: Benziger Bros., 3rd ed., 1884.

Rupp, Gordon (P), Luther’s Progress to the Diet of Worms, New York: Harper & Row, Torchbook edition, 1964.

Schaff, Philip (P), History of the Christian Church, New York: Charles Scribner’s sons, 1910, 7 volumes; available online.

Sessions, Kyle C. (P?), editor, Reformation and Authority: The Meaning of the Peasant’s Revolt, Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath & Co., 1968.

Smith, Preserved (S), The Life and Letters of Martin Luther, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911.

Smith, Preserved (S) [2], The Reformation in Europe, New York: Collier Books, 1966 — Book I of the author’s work, The Age of the Reformation, New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1920.

Spitz, Lewis W. (P), editor, The Reformation: Basic Interpretations, Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath & Co., 1962.

[go to Part II]