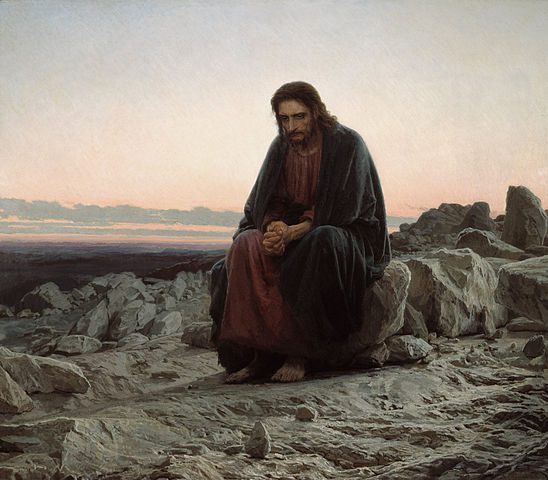

Christ in the Wilderness (1872), by Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi (1837-1887) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(3-28-08)

***

* * * * *

March 25

The Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Commonly called Lady Day

from Butler’s Lives of the Saints for March 25, page 674:

. . . the mystery of love and mercy promised to mankind thousands of years earlier, foretold by so many prophets, desired by so many saints, is accomplished upon earth. In that instant the Word of God becomes for ever united to manhood: the soul of Jesus Christ, produced from nothing, begins to enjoy God and to know all things, past, present and to come: at that moment God begins to have a worshipper who is infinite, and the world a mediator who is omnipotent: and to the working of this great mystery Mary alone is chosen to co-operate by her free assent.

Was Jesus in two (or all) places at once during His earthly life? Was He omnipresent?

According to the Church, in His human nature, Jesus was not omnipresent, but in His divine nature (that was always present alongside His human nature) He continued to be omnipresent. This is an aspect of the Hypostatic Union. In the Incarnation, Jesus took on human nature, but He retained His divine nature (which was necessarily the case, since God in His essence cannot change, and Jesus is God).

It gets extremely heavy, but here is how Catholic theologian Ludwig Ott describes this aspect of Christology, the communicatio idiomatum:

The human and the divine activities predicated of Christ in Holy Writ and in the Fathers may not be divided between persons or hypostases, the Man-Christ and the God-Logos, but must be attributed to the one Christ, the Logos become Flesh . . . It is the Divine Logos, who suffered in the flesh, was crucified, and rose again . . . (Ludwig Ott, Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, p. 144)

Christ’s Divine and Human characteristics and activities are to be predicated of the one Word Incarnate. (De fide.)

As Christ’s Divine Person subsists in two natures, and may be referred to either of those two natures, so human things can be asserted of the son of God and Divine things of the Son of Man.[ . . .]

The nature of the Hypostatic Union is such that while on the one hand things pertaining to both the Divine and Human nature can be attributed to the person of Christ, on the other hand things specifically belonging to one nature cannot be predicated of the other nature [Lutherans fall into this error]. Since concrete terms (God, Son of God, Son of Man, Christ the Almighty) designate the Hypostasis and abstract terms (Godhead, humanity, omnipotence) the nature, the following rule may be laid down: communicatio idioamatum fit in concreto, non in abstracto. The communication of idioms is valid for concrete terms not for abstract ones. So, for example: The Son of Man died on the Cross; Jesus created the world. The rule is not valid if . . . the concrete term is limited to one nature. Thus it is false to say “Christ has suffered as God.” “Christ created the world as a human being.” It must also be observed that the essential parts of the human nature, body and soul are referred to the nature, whose parts they are. Thus it is false to say: “Christ’s soul is omniscient,” “Christ’s body is ubiquitous.”

Further, predication of idioms is valid in positive statements not in negative ones, as nothing may be denied to Christ which belongs to Him according to either nature. One, therefore, may not say: “The Son of God has not suffered,” “Jesus is not almighty.” (ibid., , pp. 160-161; italics added)

So Jesus has a soul? If so, where is His soul now?

He’s in heaven at the right hand of God. Jesus continues to be one Divine Person (God the Son) with a human nature and a divine nature. He rose from the dead and possessed (unlike the Father or Holy Spirit) a glorified human body, that continues to exist forever. Along with His human nature and body is also human intellect and a human soul. The soul is a human thing: the immaterial and immortal part of a human being: the portion that continues when the body dies, and where our identity really lies. So when Christ took on human nature He also acquired a soul. God the Father doesn’t have a soul, nor does God the Holy Spirit.

For more on this, see: Catholic Encyclopedia: “Knowledge of Christ”.

How do Catholics distinguish between “soul” and “spirit”?

From Catholic Encyclopedia: “Spirit”:

(Latin spiritus, spirare, “to breathe”; Gk. pneuma; Fr. esprit; Ger. Geist). As these names show, the principle of life was often represented under the figure of a breath of air. The breath is the most obvious symptom of life, its cessation the invariable mark of death; invisible and impalpable, it stands for the unseen mysterious force behind the vital processes. Accordingly we find the word “spirit” used in several different but allied senses: (1) as signifying aliving, intelligent, incorporeal being, such as the soul; (2) as the fiery essence or breath (the Stoic pneuma) which was supposed to be the universal vital force; (3) as signifying some refined form of bodily substance, a fluid believed to act as a medium between mind and the grosser matter of the body.

. . . In Theology, the uses of the word are various. In the New Testament, it signifies sometimes the soul of man (generally its highest part, e.g., “the spirit is willing”), sometimes the supernatural action of God in man, sometimes the Holy Ghost (“the Spirit of Truth Whom the world cannot receive”). The use of this term to signify the supernatural life of grace is the explanation of St. Paul’s language about the spiritual and the carnal man and his enumeration of the three elements, spirit, soul, and body, . . .

(cf. Catholic Encyclopedia: “Soul”)

Was Butler implying that Jesus Christ was created?

We mustn’t ever say “creation of Jesus Christ.” That is the Arian heresy (now held by Jehovah’s Witnesses and Christadelphians) that reduces Jesus to a mere creature. What was created was Jesus’ human body and soul and human intellect. That was the new thing: “God became man.” The quote in Butler (above) was:

. . . the soul of Jesus Christ, produced from nothing . . .

God gained a worshiper at the Incarnation that He didn’t have before? Huh?

The worship of Jesus towards His Father is a bit different insofar as this is one member of the Godhead paying homage to another, whereas our worship is that of the fundamentally and essentially lesser or inferior creature towards the infinite Creator (adoration). With Jesus and His Father, it is the relationship of subordination that Jesus willingly took on when He became man (Philippians 2:5-11: what is called the kenosis). In that sense he “worships” His Father, while at all times remaining equal to Him in essence.

Accordingly, I submit that this distinction may be the reason why I haven’t been able to find anywhere in the New Testament where Jesus “worships” the Father (Greek: proskuneo), or “the Son worshiped the Father,” etc. If anyone finds such a verse, please let me know. The Greek word (usually “worship” in English translation) is frequently applied to people worshiping Jesus or the Father.

But, of course, as an observant Jew, Jesus attended temple and synagogue services and worshiped the Father insofar as the services involved that. One might say this was similar to His getting baptized, even though He had no sin to get rid of. It was more of a love relationship and the submission of Son to Father within the trinitarian Godhead, without implying inequality. Jesus also “submitted” to Mary and Joseph (Luke 2:51) and He certainly wasn’t inferior to them.

See also: Catholic Encyclopedia: “Christian Worship”.

Is it true and correct to assert that Jesus was not fully divine from eternity?

The heresy of Nestorianism claimed that Jesus grew in consciousness to figure out that He was God. This is in direct contradiction to the orthodox Christology of the Council of Chalcedon in 451, but it is very common in liberal theological circles and even (mostly unwittingly) in more orthodox Protestant realms.

The Butler quote merely stated that the soul of Jesus had a beginning; was created. That’s perfectly orthodox and doesn’t deny His divinity in the least. To say that Jesus was created, on the other hand, is the heresy of Arianism.

The Incarnation was something new, that had a starting-point in time. But the divinity of Jesus never had a beginning anymore than the divinity of God the Father or the Holy Spirit did. All three Persons are eternal, and God. The Hypostatic Union was the development in Christology that sought to explain the relationship of the Divine and Human Natures in Jesus. He acquired the latter but always possessed the former, from eternity.

Lots of folks today either don’t understand these things or outright deny them. This is why we have the Church, to guide us into correct theology, because, as with a journey to another town, a mere foot in the wrong direction initially can lead to being 500 miles off-target later on.

* * *

Does 1 Corinthians 15:28 suggest worship of the Father from the Son?

When all things are subjected to him, then the Son himself will also be subjected to him who put all things under him, that God may be everything to every one.

(RSV, as throughout; Rheims / KJV: “all in all”)

Also, Jesus says:

John 8:28–29 When you have lifted up the Son of man, then you will know that I am he, and that I do nothing on my own authority but speak thus as the Father taught me. And he who sent me is with me; he has not left me alone, for I always do what is pleasing to him.

John 10:30 I and the Father are one.

John 14:28 The Father is greater than I.

I’d still have to say, though, that those come under the general area of “submission” rather than worship per se. I would note, too, that we have the motif of Jesus submitting to the Father, but there are also indications of something roughly (but probably not quite) the opposite of that. You noted 1 Corinthians 15:28: “that God may be all in all” but there is also Colossians 3:11: “. . . Christ is all, and in all.”

Note that the Jehovah’s Witnesses distort this verse (1 Cor 15:28) and also John 14:28 to “prove” that Jesus was a created being and lesser than God. The following passages round out the “biblical picture” a bit:

John 16:15 All that the Father has is mine; therefore I said that he will take what is mine and declare it to you.

John 16:23-24 In that day you will ask nothing of me. Truly, truly, I say to you, if you ask anything of the Father, he will give it to you in my name. Hitherto you have asked nothing in my name; ask, and you will receive, that your joy may be full.

Orthodox Christology depends very much on how we phrase things (just like the old conciliar discussions of homoousion). As a human baby, Jesus did not understand all things. His human nature was limited and so He had to learn within that nature, like anyone else. But the Divine Nature was also present at all times, side-by-side with the human, and in the Divine Nature He did understand all things, being omniscient. And what is said of the Divine Nature can be said of Jesus the Person. It’s tough to discuss because the categories (like the Holy Trinity) are foreign to our own experience. But we have no choice. This is how God has revealed Himself.

Explain how Jesus could be present in heaven as God while He was also present here on earth? This is difficult for us to grasp.

Jesus was a Spirit (the Logos / Word) before He became a man. He didn’t cease to become a divine spirit when He became man, because God is a Spirit, and God is omniscient. On the other hand, Jesus’ unique role in the Holy Trinity is to be a flesh-and-blood man, so in a sense He is “completed” at the Incarnation, and so I think we can say that the “whole Jesus” as He would be henceforth for eternity (in a glorified sense) was present on the earth when He was here with us, in the first century.

It’s no more implausible or difficult to accept, I think, that Jesus could be bodily on the earth (as Messiah and God the Incarnate Son) and spiritually in heaven (as Logos) at the same time, as it is to believe that God can be three Persons simultaneously and remain one God, with the Son on earth praying to the Father in heaven (and both being the one God), the Father sending the Son, the Holy Spirit indwelling all believers, etc. It’s another mystery, for sure, but no more so than what we are already familiar with.

Orthodox Christians emphasize that the entire Incarnation, and Jesus’ entire life, death, Resurrection, and Ascension saves us, as opposed to Jesus’ death on the cross alone, and that human nature is raised to partake in a sense in divine nature (theosis or divinization).

I love theosis, and have written about it. It’s true that the East emphasizes this more, but it is contrary to nothing in Western Christianity, and the Catechism mentions it several times (#398, 460, 1129, 1265, 1812, 1988).

In fact, our emphasis on things like the Mediatorship of Mary could be defended by analogy on these grounds (as I have done). God makes us more like Him and so He chooses to distribute grace through Mary. That’s because God has raised human beings (and especially the Blessed Virgin) to such a high state due to the Incarnation.

The citation from Ott is very abstract and heavy. I always have to read it several times myself to make sure I grasp it (as all truly good philosophy requires one to do). The key is the following portion:

As Christ’s Divine Person subsists in two natures, and may be referred to either of those two natures, so human things can be asserted of the son of God and Divine things of the Son of Man.

To say, for example, “Jesus is omnipresent,” is perfectly fine, because Jesus is the Person Who has the Two Natures. Whatever is true in either Nature can be said of the Divine Person, Jesus. A dim analogy would be our possessing both a body and a soul. What is true of either can be referred to us as a person:

“My (i.e., this person, Dave Armstrong’s) soul cannot be physically harmed or destroyed.”

“I (i.e., my body) can be physically harmed or killed.”

When I say “I will live forever” that is primarily referring to my immaterial soul (though we will receive resurrection bodies too). If I say “I will die, just like every other person,” then I am referring to the limitations of a physical body. Death, in fact, is literally the separation of soul and body. It is not the destruction of the soul (as in the false view of annihilation or denial of immortality of the soul). Therefore, death by definition must refer to only one part of us ceasing to exist (our body) but not the other part, the soul. But we generally simply say, “I will eventually die.”

With Jesus it is a little more complex, because He is both God and Man, and He has a Divine Nature and a human nature side-by-side, and these are not identical. We can assert, “Jesus is omnipresent” because in His Divine Nature He is. We can also say “Jesus learned like a man” or “Jesus was in one place at one time while on the earth” because those statements are referring to His human nature (without saying it: it is the unspoken premise).

We can even say (somewhat surprisingly at first glance) that “God died.” That is orthodox Catholic theology, because Jesus was God. God became Man, and this Divine Person and Man died (i.e., in His human nature). Therefore, God died.

What we can’t do is confuse the natures with each other, and say something like “In His human nature, Jesus was omnipresent.” That is untrue. We can’t say, “Jesus as the Eternal Word / Logos before the Incarnation was spatially limited.” He (as Logos) isn’t in space at all, because He is a spirit. And as an eternal Spirit, He wasn’t in time, either, so to even refer to “was” in this context is inaccurate (which is why Jesus said, “before Abraham was, I am” — John 8:58).

The reasoning is also similar in the theology of Mary as Theotokos, or “Mother of God” or “God-bearer.” We can say that because Jesus is God! Mary didn’t just give birth to the human nature of Jesus, but to the Divine Person, Jesus. Therefore, we can assert that she was the Mother of God. She bore, of course (another unspoken, assumed premise) the incarnate God (as opposed to the eternal Spirit Who cannot be conceived and given birth to, being both Spirit and eternal and ungenerated), but He was still God.

As another way of looking at it, we don’t describe human mothers in the following ways: “she gave birth to a soul” or “Sue gave birth to yet another human body at 4:03 AM today.” We say, “Jane gave birth to a healthy baby boy, Bocephus, at 4:03 AM today.” We say this, knowing that the soul is a direct creation of God. Birth is not creation, but procreation. Parents played a role in the physical bodies of their offspring (by genetics and reproduction) but not the souls. Yet we always refer to the person born, who is composed of both body and soul.

Thus, we could state, “Jane gave birth to Bocephus, who possesses an eternal soul made in the image of God.”

Another (quite imperfect) analogy would be our struggle between “flesh” and “spirit.” They are two parts of us that war against each other. We are fallen creatures and children of Adam, yet when regenerated we become children of God. When we’re led by the Indwelling Spirit we are doing what we are created to do, but when led by the flesh or the devil, through concupiscence and temptation, we are following another spirit.

All these analogies are trying to show instances of one person who has more than one part. In Jesus’ case (Two Natures or Hypostatic Union) they always work together and are harmonious, though distinct. The same applies to the distinction of Persons within the Holy Trinity.

Created human beings have a body and a soul, and a flesh and a spirit (in the spiritual sense). The huge and essential difference in our case is that we have internal conflict, whereas God does not. But the analogies help us to comprehend how Jesus could have both a Divine Nature and a human nature.

I love “analogical argument.” I hope this has been helpful and not further confusing. It helps me, too, to better understand the Incarnation and the Hypostatic Union, even while I am writing.