(3-3-04; additions from 10-9-07)

***

From my review of the movie Luther:

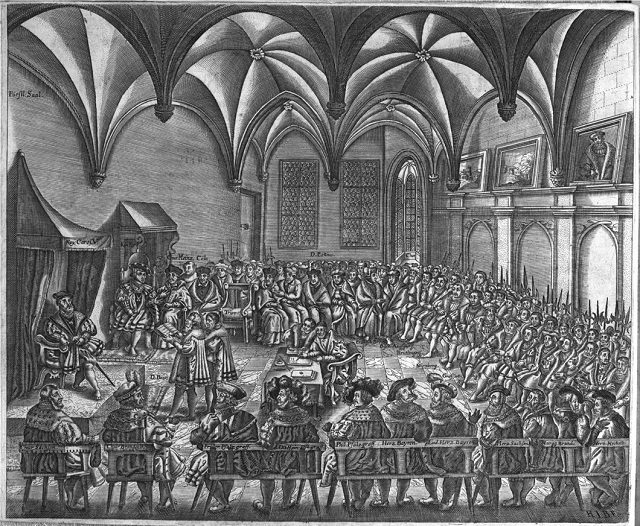

The movie ended with the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 between Protestants and Catholics, and the Protestant “triumph” — as their “case” was allowed to be presented (announced on the hilltops by jubilant Protestants to the surprised Luther). Then writing appears on the screen to the effect that these momentous events heralded a huge step forward for the cause of religious liberty and freedom of conscience.

If the stereotypes of the movie are to be believed, the Protestant princes and other representatives were (to a man), noble, selfless, sincere, committed Christians who simply wanted to worship in peace and to read their Bibles in German without harassment. The Catholics, represented in the scene primarily by Emperor Charles V, only wanted (as the myth would have it) to suppress the Bible, so that no one would see the self-evident biblical truth that Catholicism was false.

The reality, was, of course, far more interesting and complex. Protestant historian Philip Schaff (the very definition of a “biased but fair-minded person”) wrote in his History of the Christian Church:

The Emperor stood by the Pope and the Edict of Worms, but was more moderate than his fanatical surroundings, and treated the Lutherans during the Diet with courteous consideration, while he refused to give the Zwinglians even a hearing. The Lutherans on their part praised him beyond his merits, and were deceived into false hopes; while they would have nothing to do with the Swiss and Strassburgers, although they agreed with them in fourteen out of fifteen articles of faith . . .

Margrave George of Brandenburg declared that he would rather lose his head than deny God. The Emperor replied: ‘Dear prince, not head off, not head off’ . . .

The only blot on the fame of the Lutheran confessors of Augsburg is their intolerant conduct towards the Reformed, which weakened their own cause. The four German cities which sympathized with the Zwinglian view on the Lord’s Supper wished to sign the Confession, with the exception of the tenth article, which rejects their view; but they were excluded, and forced to hand in a separate confession of faith.

Even Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon couldn’t come to full agreement on matters connected with the Augsburg Confession, as indicated by a series of letters between them at the time of the Diet of Augsburg. Melanchthon, true to his more conciliatory, mild character, took a much different approach than Luther:

He sweated over every portion of the Apology, for he wanted to state the core of evangelical doctrine without alienating the Roman Catholics. (Melanchthon: The Quiet Reformer, Clyde Leonard Manschreck, New York: Abingdon Press, 1958, 182)

The nature of the Mass was a dividing point all along, and indicates the contradictory nature of the Lutheran position, that was claiming to be a continuation of “catholic history” but in fact was an innovation, if it didn’t even retain the central act of Christian worship, according to all those centuries from the time of Christ to 1517. Melanchthon biographer Manschreck subtly notes this disconnect:

Melanchthon’s letters that Sunday afternoon, June 19, to Myconius, Luther, and Camerarius show that he thought the entire dispute might be settled by correcting abuses. Melanchthon believed that the evangelical movement in Germany was a product of the vital spirit of the old Latin church, that the fundamental doctrines of justification by faith were not anything new but a reassertion of the heart of the Christian gospel, which in the centuries of church development had become obscured by ecclesiastical observances. In casting these aside Melanchthon believed the evangelicals were adhering to the pristine practices of the church, as reflected in Scripture and the early fathers, particularly Augustine. To Valdes he was trying to show that the reformation practices were in accord with the old canonical rules and compliant with genuine catholic Christianity, and ought, therefore, to be tolerated and encouraged by the Emperor.

But something happened. Although the evangelicals attended the early morning mass, June 20, as requested . . . not a single evangelical representative participated in the ancient, mysterious rites. Charles showed his displeasure, but the Protestants seemed to have determined upon another course of action. (Manschreck, ibid., 190)

Luther (as we would fully expect) was far less conciliatory than Melanchthon. He wrote to the latter on 28 or 29 June 1530:

I have received your Apology, and I am wondering what you mean when you say you desire to know what and how much we may yield to the Papists? According to my opinion, too much is already conceded to them in the Apology . . . I am ready, as I have always written to you, to yield up everything to them, if they will only leave the Gospel free. (Ibid., 195)

Luther seems to have thought (far differently than Melanchthon) that reconciliation with the Catholics was impossible. Indeed, Manschreck noted that “Historians writing on the Augsburg Confession usually criticize Melanchthon as childish if not traitorous for his activity during this period” (p. 204). He contends that Luther himself would not agree with such an assessment of his friend and successor, but clearly saw “that the basic difference was one of authority” (p. 205).

The very notion that the Augsburg Confession was in entire agreement with prior Catholic history is quite debatable. Catholic Luther biographer Hartmann Grisar wrote:

In fact, the first official edition of the “Confession,” printed in 1530, contained the deceptive declaration (which was subsequently altered) that the impugned doctrines meant no deviation from the Scriptures or the teaching of the Roman Catholic Church, in as far as that teaching could be ascertained from Catholic authors.

. . . the Catholic theologians . . . noted the absence of any declaration relative to the pope, whom the Lutherans had come to regard as Antichrist. The declaration was silent about the universal priesthood of all the faithful in place of the clergy, the incapacity of the human will to do good, and absolute predestination, the very pillars of the doctrinal system of Lutheranism. The antitheses between the two religions on the subject of indulgences and Purgatory were likewise hushed up, and the differences in the veneration of the saints had also vanished.

Hence, honest candor, the preliminary condition of reunion, was missing. (Martin Luther: His Life and Work, translated by Frank J. Eble, edited by Arthur Preuss, Westminster, Maryland: The Newman Press, 1950, 376)

Grisar says of Melanchthon that “His depressed condition of mind is the only thing that helps him over the charge of conscious deception” (p. 377). He implies that Luther (in his letter of August 26th, 1530, partially cited above) was aware of a certain “vacillation” — or at least likely perceptions of same — from the Protestants in the negotiations of Augsburg:

. . . we shall be charged with perfidy and vacillation. But what will the consequence be? Matters may easily be remedied by the steadfastness and the truth of our cause. True, I do not wish that it should so happen; but speak in such wise that, if it should happen, despondency do not ensue. For, once we shall have attained peace and escaped violence, we shall easily make amends for our tricks . . and failings, because God’s mercy rules over us. (Ibid., p. 388)

Catholic historian Warren Carroll described the proceedings and the lack of tolerance in the Lutheran party:

Early in July the bishops presented their complaints to the Diet of the plundering and destruction of churches, seizure of monasteries and hospitals, prohibition of Masses, and attacks on religious processions by the Protestants. When Charles called upon the Protestants to restore the property they had seized, they said that to do so would be against their consciences. Charles responded crushingly: ‘The Word of God, the Gospel, and every law civil and canonical, forbid a man to appropriate to himself the property of another.’ He said that as Emperor he had the duty of guarding the rights of all, especially those Catholics unwilling to accept Protestantism or go into exile, who should at least be allowed to remain in their homes and practice their ancestral faith, specifically the Mass; the Protestants replied that they would not tolerate the Mass . . .

By July it was clear that on matters of doctrine the Lutherans at Augsburg were dissimulating, concealing their real beliefs in the hope of avoiding a final breach without making genuine concessions. On July 6 Melanchthon made the incredible statement:

We have no dogmas which differ from the Roman Church . . . We reverence the authority of the Pope of Rome, and are prepared to remain in allegiance to the Church if only the Pope does not repudiate us.

As it happened, on the very same day Luther, in an exposition on the Second Psalm addressed to Archbishop Albert of Mainz, declared:

Remember that you are not dealing with human beings when you have affairs with the Pope and his crew, but with veritable devils! . . .

On the 13th [of July] Luther announced from Coburg that the Protestants would never tolerate the Mass, which he called blasphemous, and said of the Emperor:

We know that he is in error and that he is striving against the Gospel . . . He does not conform to God’s Word and we do . . .

Luther stated in a letter to Melanchthon [on] August 26:

This talk of compromise . . . is a scandal to God . . . I am thoroughly displeased with this negotiating concerning union in doctrine, since it is utterly impossible unless the Pope wishes to take away his power.

In subsequent letters he declared that no religious settlement was possible as long as the Pope remained and the Mass was unchanged . . .

Luther prepared the final Protestant answer:

The Augsburg Confession must endure, as the true and unadulterated Word of God, until the great Judgment Day . . . Not even an angel from Heaven could alter a syllable of it, and any angel who dared to do so must be accursed and damned . . . The stipulations made that monks and nuns still dwelling in their cloisters should not be expelled, and that the Mass should not be abolished, could not be accepted; for whoever acts against his conscience simply paves his way to Hell. The monastic life and the Mass covered with infamous ignominy the merit and suffering of Christ. Of all the horrors and abominations that could be mentioned, the Mass was the greatest.

. . . no Catholic of spirit and courage could be expected, let alone morally required, to give up all his religious rights without a struggle; and few Protestants, at this point, would allow Catholics to exercise those rights if the Protestants were strong enough to deny them. These were the irreconcilable positions taken by the two sides at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, which made those long and bloody years of conflict inevitable. (The Cleaving of Christendom; from the series, A History of Christendom, Volume 4, Front Royal, Virginia: Christendom Press, 2000, 103-107)

So we see that this supposedly wonderful newfound “tolerance” and freedom of worship among the early Protestants was shot through with hypocrisy. The Lutherans were obviously courting the Catholic Emperor’s favor (putting politics above principle to some extent), whereas they would have “nothing to do” with their fellow Protestants, the Swiss and Strassburg theologians, even though they disagreed on one article of fifteen; and the Zwinglians wouldn’t sign the confession because of dissent on one article. They held to a symbolic view of the Eucharist (identical to the view of the majority of evangelical Christians today).

And of course, at the same time or shortly thereafter, Luther and Melanchthon and the Zwinglians and Calvinists were executing Anabaptists (who weren’t allowed to speak at all at the Diet of Augsburg) because they believed in adult baptism (like today’s Baptists), and forbidding religious freedom to Catholics. Catholics were required to give up their belief in the authority of the pope and their central religious rite, the Mass; Catholic properties which were stolen and plundered would not be returned, in the name of “conscience,” while the Augsburg Conession is an oracle from God; indeed the veritable “Word of God” itself, practically divinely inspired in every syllable (according to Quasi-Prophet Luther).

This is “tolerance” and “religious freedom”? How does one “negotiate” with such people, who consider every utterance in their statements inspired and infallible and their opponents “devils” who engage in “blasphemy” every Sunday when they worship? Truth is always stranger and more fascinating than fiction.

Nor were things very “tolerant” in Augsburg itself, in matters religious, following the Diet. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:

At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, at which the so-called Augsburg Confession was delivered to Emperor V in the chapel of the episcopal palace, the emperor issued an edict according to which all innovations were to be abolished, and Catholics reinstated in their rights and property. The city council, however, set itself up in opposition, recalled (1531) the Protestant preachers who had been expatriated, suppressed Catholic services in all churches except the cathedral (1534), and in 1537 joined the League of Smalkald. At the beginning of this year a decree of the council was made, forbidding everywhere the celebration of Mass, preaching, and all ecclesiastical ceremonies, and giving to the Catholic clergy the alternative of enrolling themselves anew as citizens or leaving the city. An overwhelming majority of both secular and regular clergy chose banishment; the bishop withdrew with the cathedral chapter to Dillingen, whence he addressed to the pope and the emperor an appeal for the redress of his grievances. In the city of Augsburg the Catholic churches were seized by Lutheran and Zwinglian preachers; at the command of the council pictures were removed, and at the instigation of Bucer and others a disgraceful storm of popular iconoclasm followed, resulting in the destruction of many splendid monuments of art and antiquity. The greatest intolerance was exercised towards the Catholics who had remained in the city; their schools were dissolved; parents were compelled to send their children to Lutheran institutions; it was even forbidden to hear Mass outside the city under severe penalties.

***

Photo credit: Reading of the Confessio Augustana in front of Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Augsburg, 1530 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***