The political and religious views of these two great men are little-known.

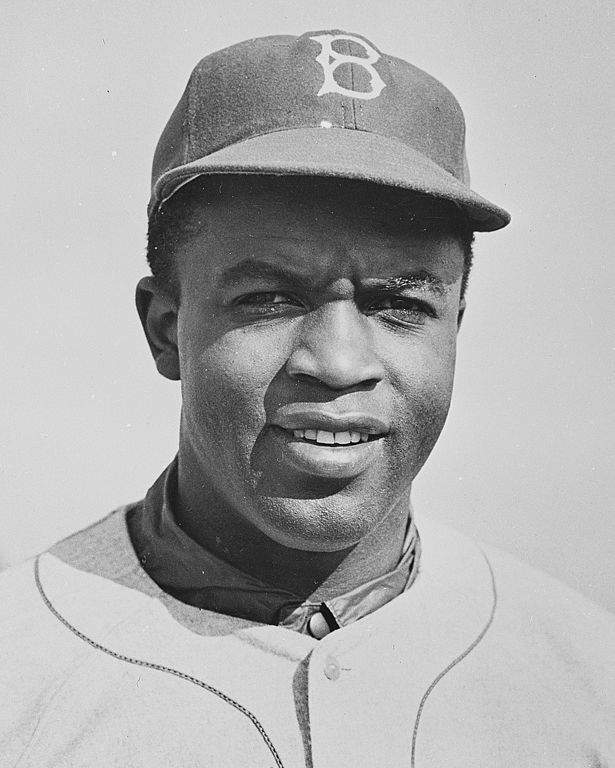

As anyone in the least familiar with the history of baseball or race relations in America knows, Jackie Robinson became the first African-American in Major League Baseball in 1947, with the Brooklyn Dodgers, due to Branch Rickey, the team’s President and General Manager. The story is very well known, so I won’t retell it here. Rather, I’d like to highlight the usual downplaying or ignoring of the political and religious aspects regarding the two men.

In the article, “With Guts Enough to Be Disarming” (First Things, April 23, 2007), Nicholas Frankovich describes Rickey’s affiliations:

. . . Rickey read to Robinson some familiar words from the Sermon on the Mount: “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: but I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy cheek, turn to him the other also.”

“I have two cheeks, Mr. Rickey,” Robinson answered. “Is that it?” That was it.

My source for this rendition of that first meeting between Rickey and Robinson is ‘Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman,’ a gracefully narrated, amply documented biography by baseball writer Lee Lowenfish. . . .

Most of us have not come to know the part about the Christianity, about the Sermon on the Mount being Robinson’s playbook for how to handle the racial animus he was sure to encounter, or about how Rickey’s feelings for racial justice flowed from his conservative brand of Protestantism. (Even in his short-lived career as a player, he wouldn’t step into a ballpark on Sundays.) In his politics, Rickey was a stalwart Republican, supporting every candidate his party nominated to oppose FDR, whose muscular foreign policy against the fascist threat abroad was the one point on which Rickey agreed with him. For Rickey, who was born in 1881, the GOP meant, besides free enterprise and anticommunism, Lincoln and the antislavery movement, and it fit nicely with his religiously informed views on contemporary racial issues.

But the only culture at the middle of the twentieth century was, as Lionel Trilling famously commented, liberal culture, and so the story that has come down to us is that the fight to end desegregation was essentially a liberal cause. Secular liberals did play their part in their ad hoc alliance with the churches, whose own contribution to the civil-rights era is not much recognized anymore. . . . American kids today grow up thinking that the fight for racial equality is something that the Democratic party won while the likes of Branch Rickey—conservative Republicans, devout Christians—were actually out there with Bull Connor hosing down the demonstrators.

Lowenfish in his biography scrapes away all that crust and shows us the historical reality for what it was. It’s not a conservative book and Lowenfish is not a conservative writer or, to my knowledge, a Christian, but he’s honest and fair in his treatment of the conservative and Christian that was Branch Rickey, whom he clearly admires.

It turns out that Jackie Robinson was no political liberal, either, according to biographer Arnold Rampersad and reviewer Donald Kagan:

Malcolm X, for one, attacked Robinson for attempting to defuse rather than to fan black rage. Sympathizing with blacks frustrated by the slowness of progress, Robinson nevertheless stood firm in his integrationist principles, and was prepared to defend “establishment” blacks like Ralph Bunche, then serving as U.S. ambassador to the UN. In the wake of charges by Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell that Bunche had “sold out,” Robinson boldly retorted that “Malcolm is very militant on Harlem street comers where militancy is not dangerous,” but that he lacked “one-twentieth of the integrity and leadership” of a man like Bunche. For this and other, similar statements Robinson would himself be accused of being an Uncle Tom. Undeterred, he went his way, castigating the separatism and violence of the “black power” movement, and castigating as well the anti-Semitism that was its frequent accompaniment.

Robinson’s devotion to his country, a hopeful patriotism that marked the early civil-rights movement as a whole, was part of a broader vision in which the struggle for civil rights in America took its place within the worldwide struggle for freedom. He was, in short, a spirited and consistent anti-Communist. In 1949, the famous black singer Paul Robeson had declared, before a leftist audience in Paris, “It is unthinkable that American Negroes would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against a country [the Soviet Union] which in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind.”

Robinson, asked to give his own views before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, retorted that, if war came, American blacks would “do their best to help their country win the war-against Russia or any other enemy that threatened us.” Years later, in 1967, when such ideas were badly out of fashion, Robinson went so far as to criticize his friend and idol, Martin Luther King, Jr., for the latter’s one-sided attacks on American policy in Vietnam. “Why is it, Martin,” he asked, “that you seem to ignore the blood which is upon [Communist] hands and to speak only of the ‘guilt’ of the United States?”

Another online biography describes Robinson’s mother Mallie as “a deeply religious woman” and refers to one of his early influences:

Karl Downs, youthful minister of Robinson’s Methodist church, paced the sidelines whenever his protégé was on the playing field and counseled him when his athletic, social, or academic life became burdensome.

Rickey is described as “a devout Christian”. Robinson was not a knee-jerk Democrat:

Robinson’s political alliances were unlike those of most African Americans who shied away from the Republican Party. He campaigned for Democrat Hubert Humphrey in the presidential primary, yet he chose Republican Richard M. Nixon over John F. Kennedy in the 1960 general election. When Robinson compared his observations of the two candidates for president long after the election, he regretted he had not chosen Kennedy. During the campaign, Nixon was friendly and charming in private meetings, and seemed interested in the civil rights of African Americans. Robinson saw no tangible evidence of Nixon’s sympathy for the struggle in the South. On the other hand, when Robinson met Kennedy, he wondered whether the Democrat’s failure to make eye contact as they talked was due to an unspoken prejudice. Robinson’s fears disappeared with the news of Kennedy’s public objections to the persecution of Martin Luther King. Robinson came to the belated conclusion that Kennedy was the better man.

New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a Republican, named Robinson Special Assistant for Community Affairs in 1966, with the responsibility of improving the governor’s popularity among residents of Harlem. In response to criticism, Robinson defended his membership in the Republican Party as a way to make heard the otherwise ignored voice of black opinion.

Jimmie L. Hollis, writing in the Courier-Post Online (22 April 2007) elaborates upon this theme:

Robinson paid a cost for being a black conservative Republican. He was the first casualty of the liberals’ war to take control of the black masses. This war started during the 1960 presidential race. Until the last weeks of the campaign, no political leader, pundit or pollster could be certain which candidate — John F. Kennedy or Richard Nixon — black voters would support.

Of the major candidates for the Democratic nomination, Kennedy had been the least liberal. He had voted to weaken civil rights legislation while in Congress, so comparatively Nixon seemed far more sensitive to issues surrounding race. And it was not unusual, even in the 1960s, for black voters to look to the party of President Lincoln for leadership.

Martin Luther King Jr. had praised Nixon in the past and it was widely known that Martin Luther King Sr. was a staunch Republican as well. Robinson was keeping in touch with King and was hand-picked by the young minister to lead a church reconstruction effort in Terell County, Georgia.

But by working with Nixon and the GOP, Robinson felt he was building a permanent home at the top of the Republican Party so that intelligent decision-making could occur on both sides with respect to civil rights.

In the increasingly liberal-dominated black leadership of the 1960s, Robinson’s support of the GOP cost him not only public prestige but peace of mind. Robinson marched shoulder to shoulder with King, out front in the demand for real change. And for that all he got in return was political death fashioned by liberal blacks.

George Mitrovich wrote in the Good News Magazine (an evangelical Methodist publication: May / June 2005) about the influence of the Methodist minister Karl Everitt Downs on Jackie Robinson’s life and spirituality, and Rickey’s own committed evangelical Methodism:

“Downs led Jack back to Christ,” the author [biographer Arnold Rampersad] writes. “Under the minister’s influence, Jack not only returned to church, but also saw its true significance for the first time; he started to teach Sunday school. After punishing football games on Saturday, Jack admitted, he yearned to sleep late: ‘But no matter how terrible I felt, I had to get up. It was impossible to shirk duty when Karl Downs was involved. Karl Downs had the ability to communicate with you spiritually,’ Jack declared, ‘and at the same time he was fun to be with. He participated with us in our sports. Most importantly, he knew how to listen. Often when I was deeply concerned about personal crises, I went to him.’

“Downs became a conduit through which Mallie’s message of religion and hope finally flowed into Jack’s consciousness and was fully accepted there. Faith in God then began to register in him as both a mysterious force, beyond his comprehension, and as a pragmatic way to negotiate the world. A measure of emotional and spiritual poise such as he had never known at last entered his life.

Robinson himself would say, “I had a lot of faith in God. There’s nothing like faith in God to help a fellow who gets booted around once in a while.”

The influence of his mother, Mallie, and his pastor, Karl Downs, would forever affect the way Jackie Robinson lived his life, how he saw other people, and how he coped with discrimination. He had been taught that he was a child of God, and no one and no challenge, however brutal and dehumanizing, could take that away from him.

Why did Rickey find those experiences of the young Jackie so persuasive? Branch Rickey was also a Methodist. Not just a Methodist, but, according to Rampersad, “a dedicated, Bible-loving Christian who refused to attend games on Sunday.” His full name was Wesley Branch Rickey. He was a graduate of Ohio Wesleyan University-and the influence of the Methodist Church was a great factor in his life.

. . . As one Methodist believer to another, Rickey offered Jack an English translation of [Catholic] Giovanni Papini’s Life of Christ and pointed to a passage quoting the words of Jesus-what Papini called ‘the most stupefying of His revolutionary teachings’: ‘Ye have heard that it hath been said, an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, that ye resist not evil: But whosoever shall smite thee on thy right check, turn to him the other also. And if a man will sue thee at the law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain.'”

***

(originally 4-26-07)

Photo credit: Jackie Robinson in his Brooklyn Dodgers uniform, 1950. [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***