The debate among equally orthodox Catholics on the death penalty continues . . .

***

Dr. Robert Fastiggi has made a series of replies (in the combox), to Dr. Edward Feser’s article, “Capital punishment and the infallibility of the ordinary Magisterium” (Catholic World Report, 1-20-18). Dr. Feser (who seems to have much more time for this sort of thing than Dr. Fastiggi does) has already responded at length. I have collected Dr. Fastiggi’s comments here:

*****

I commend Prof Feser for his desire to defend his position, and I thank him for taking some of my points seriously even though he doesn’t agree with them. Obviously an article of the length he gives deserves a detailed response. Right now, I don’t have the time to do that, so I’ll make a few points. First, I should note that Feser cites Lumen Gentium, 12 in support of the universal agreement of the faithful on matters of faith and morals. He fails, though, to mention that this universal agreement “is exercised under the guidance of the sacred teaching authority, in faithful and respectful obedience to which the people of God accepts that which is not just the word of men but truly the word of God.” This last sentence underlines the role of the magisterium in determining whether a teaching is definitive and infallible or whether it isn’t.

Prof. Feser and his followers have every right to argue their case that the legitimacy of capital punishment in principle is an infallible teaching of the ordinary and universal magisterium. It’s always helpful, though, for the magisterium itself to confirm that a teaching is infallible by means of the ordinary and universal magisterium—as St. John Paul II did in Evangelium Vitae with respect to the grave evil of direct abortion (n. 62) and euthanasia (n. 65).

Trying to determine which teachings are infallible by virtue of the ordinary and universal magisterium, however, is not any easy task. In his article, it would have been good for Feser to cite Lumen Gentium, 25, which notes that the ordinary and universal magisterium is infallible when the Catholic bishops “maintaining the bond of communion among themselves and with the successor of Peter, and authentically teaching matters of faith and morals, are in agreement on one position as definitively to be held.” This sets a very high standard, for it’s not so easy to verify whether the bishops, teaching in communion with the Roman Pontiff, have come to an agreement that one position (unam sententiam) on faith or morals must be definitively held.

I’ve been teaching Catholic ecclesiology at the university or seminary level for over 30 years, and I’ve learned to be very careful when giving examples of teachings that are infallible by virtue of the ordinary and universal magisterium. I try to choose examples in which there can be very little doubt for faithful Catholics. For example, the perpetual virginity of Mary has never been defined by either an ecumenical council or an ex cathedra papal pronouncement. But those who have challenged it have been condemned in no uncertain terms (see canon 3 of the Lateran Synod of 649 in Denz.-H, 503 and Paul IV’s 1555 constitution against the Unitarians in Denz.-H, 1880).

Moreover, the perpetual virginity of Mary is affirmed in the liturgy (e.g. the Roman Canon). Another example I give is the reality of angels and demons as real creatures of intellect and will and not mere abstractions. The 1215 Profession of Faith of Lateran IV affirms their real existence as does the liturgical life of the Church (how could the empty promises of an abstraction be rejected during the Rite of Baptism?). During the late 1960s and early 1970s, though, some Catholics began questioning the real existence of angels and demons. Bl. Paul VI reaffirmed the existence of angels in his 1968 Credo of the People of God and the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith reaffirmed the existence of demons in its 1975 document, Christian Faith and Demonology.

When compared to dogmas such as the perpetual virginity or Mary or the reality of angels and demons, the dogmatic status of legitimacy of capital punishment comes across as far less certain. This is not to ignore the sources that Feser cites. Rather, it is a simple recognition that these sources do not reach the level of a definitive judgment of the ordinary and universal magisterium.

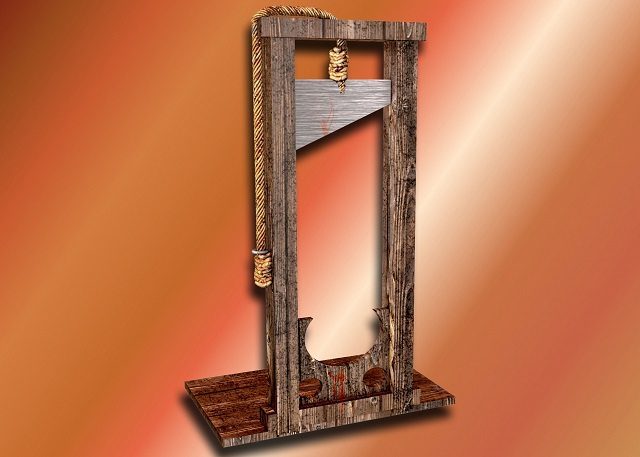

The magisterium itself is usually the best source for determining which teachings of the ordinary and universal magisterium are infallible and which are not. When subsequent popes show they are not bound by judgments of their predecessors, that’s a good indication that those judgments were not definitive. For example, Pope Innocent I in 405 alludes to Rom 13 is granting permission for the civil authorities of Toulouse to have recourse to judicial torture and capital punishment. Pope Nicholas I, however, in 866 states that such torture is not allowed by either divine or human law (Denz.-H., 648). So it’s clear that Nicholas I in 866 did not feel bound by what Innocent I taught in 405.

St. John Paul II likewise did not feel bound by prior magisterial teachings that seemed to affirm the legitimacy of the death penalty for reasons of retribution. Instead, in his 1995 encyclical, Evangelium Vitae, he limited any possible use of capital punishment to societal self-defense (n. 55). Therefore, he forbade recourse to the death penalty except in cases of absolute necessity “when it would not be possible otherwise to defend society;” and he also noted that such cases today “are very rare, if not practical non-existent” (n. 56).

Professor Feser, in his book co-authored with Prof. Bessette, states that St. John Paul II’s position “is a mistake, and a serious one” (p. 197). This, though, means that since 1995 the magisterium has been habitually mistaken on a prudential judgment (and it’s really much more than prudential). Feser, therefore, contradicts the very passage from the CDF’s 1990 instruction, Donum Veritatis, that he cites: namely “It would be contrary to the truth, if, proceeding from some particular cases, one were to conclude that the Church’s Magisterium can be habitually mistaken in its prudential judgments, or that it does not enjoy divine assistance in the integral exercise of its mission” (n. 24). To suggest that the magisterium has been habitually mistaken for 23 years on the death penalty seems very problematical. Does not Feser believe that the Church’s magisterium has enjoyed divine assistance in the last 23 years with regard to capital punishment?

To my mind, it’s much more likely that Feser is mistaken than St. John Paul II and his successors. This is not a “cheap shot” as Feser claimed when I previously noted that his position stood in contradiction to that of Pope Francis. Since when is it a “cheap shot” to appeal to the authority of the Roman Pontiff over that of a private scholar? Much more can be said, but this will need to suffice for now. I think Feser’s arguments are convincing to those who already favor capital punishment. They are not convincing to me and many others. If the magisterium in the future declares capital punishment—even under certain conditions—to be intrinsically evil, I’ll abide by the magisterium’s judgment. This would be an indication that there was no prior definitive magisterial teaching on the subject. Feser could shout “error” all he wants, but his shouts could never match the authority of the Catholic magisterium.

***

I think it’s inaccurate to say that St. John Paul II’s teaching on captial punishment was only prudential. Both Aquinas (ST II-II, q. 47 a. 3 ad 1) and the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC, 1806) understand prudence as the virtue by which “we apply moral primciples to particular cases.” John Paul II and the CCC teach that non-lethal means of punishment are “more in conformity with the dignity of the human person” (EV, 56, CCC, 2267). This is a principle not a prudential judgment, and it supports the other principle articulated by John Paul II in Evangelium Vitae [EV], 56, viz., that it is not licit (neque … licere) to impose the death penalty “except in cases of absolute necessity (nisi absoluta instante necessitate), namely when it would not be possible otherwise to defend society.”

Now both EV, 56 and the CCC, 2267 do invoke prudential elements (e.g. “the concrete conditions of the common good”), but a twofold principle is laid out that is meant to inform any prudential judgment regarding the death penalty: 1) that non-lethal means of punishment better correspond to human dignity; and 2) that recourse to the death penalty is not licit except in cases of absolute necessity: namely, when it would not be possible otherwise to defend society. There might be legitimate debate about what would qualify as cases of absolute necessity, but those who favor the death penalty have the burden of proof to show that recourse to capital punishment is the only possible way of defending society.

Pope Francis has now added more reasons (derived from the Gospel) for rejecting the death penalty. We should, of course, respect tradition, but there are traditions that can be changed or developed and others that cannot. Just as the tradition accepting torture has now been superseded (cf. GS, 27, and the CCC, 2297)so now the tradition accepting capital punishment is being superseded. The fact that Pope Francis and the overwhelming majority of bishops now reject capital punishment is a sign that there never was a definitive magisterial tradition on the matter.

***

I’m very sorry, but I think the 2,000 year tradition is something of a myth. Before Pope Innocent I’s permission in 405 for public officials to use torture and capital punishment there was nothing handed down in prior tradition (as Innocent I himself states). Some of the patristic sources cited by Feser and Bessette do not really show support for capital punishment (not even in principle). The teaching against euthanasia is definitive, and has been confirmed as such. Church tradition in support of capital punishment was never definitive. This is why the last three popes have all called for the end of the practice.

***

I try to follow Scripture according to the mind of the Church. If the recent papal magisterium had not spoken out against capital punishment, we could have a good debate over the subject. I am only trying to follow the mind of the Church. Like Pope Francis, I think we should work for penal reform and better prison conditions. As for deterrence, many studies do not support your findings.

***

[after Dr. Feser’s latest reply] Thank you, Prof. Feser, for taking note of my comments. I tried to post some comments on your blogspot, but I’m not sure if they went through. In any case, I don’t have time to comment in depth right now. Perhaps in the future I’ll be able to write a more thorough review of your book. For now, I’ll say this. Even if one were to concede that capital punishment was not intrinsically evil in the past, that still doesn’t mean one can dissent from the present teaching of the papal magisterium on the subject. You seem to think that, unless capital punishment is declared intrinsically evil, then any teaching about it is only prudential. This, though does not follow.

To make prudential judgments there must be moral principles, and St. John Paul II in EV, 56 and the CCC, 2267 lay out such moral principles. The Church does not regard war as intrinsically evil, but she lays out very strict conditions for any possible engagement in war (e.g. CCC, 2309). War, therefore, can only be justified according to these strict conditions. With regard to the death penalty, I am aware of of all the scriptural and historical examples you give, but I don’t believe they set forth definitive principles for deciding if and when the death penalty may be used today. Because the present magisterial teaching on the death penalty is not contradicting any definitive, infallible teaching of the past, it should be adhered to with religious assent according to Lumen gentium, 25 and the CCC, 892. The magisterium need not declare that capital punishment is intrinsically evil to determine that it is against the Gospel to kill a human being without necessity, i.e. when a person’s ability to do further harm has been neutralized and this person retains human dignity in spite of prior crimes.

***

Photo credit: Image by kai Stachowiak [PublicDomainPictures.Net / CC0 Public Domain license]

***