Servant of God John A. Hardon, S. J.

The place or condition in which the souls of the just are purified after death and before they can enter heaven. They may be purified of the guilt of their venial sins, as in this life, by an act of contrition deriving from charity and performed with the help of grace. This sorrow does not, however, affect the punishment for sins, because in the next world there is no longer any possibility of merit. The souls are certainly purified by atoning for the temporal punishments due to sin by their willing acceptance of suffering imposed by God. The sufferings in purgatory are not the same for all, but proportioned to each person’s degree of sinfulness. Moreover, these sufferings can be lessened in duration and intensity through the prayers and good works of the faithful on earth. Nor are the pains incompatible with great peace and joy, since the poor souls deeply love God and are sure they will reach heaven. As members of the Church Suffering, the souls in purgatory can intercede for the persons on earth, who are therefore encouraged to invoke their aid. Purgatory will not continue after the general judgment, but its duration for any particular soul continues until it is free from all guilt and punishment. Immediately on purification the soul is assumed into heaven. (Etym. Latin purgatorio, cleansing, purifying). (Pocket Catholic Dictionary, New York: Doubleday Image, 1980, 356-357)

C. S. Lewis (Protestant)

Of course I pray for the dead. The action is so spontaneous, so all but inevitable, that only the most compulsive theological case against it would deter me. And I hardly know how the rest of my prayers would survive if those for the dead were forbidden. At our age the majority of those we love best are dead. What sort of intercourse with God could I have if what I love best were unmentionable to Him? . . .

I believe in Purgatory . . . Our souls demand Purgatory, don’t they? Would it not break the heart if God said to us, ‘It is true, my son, that your breath smells and your rags drip with mud and slime, but we are charitable here and no one will upbraid you with these things, nor draw away from you. Enter into the joy’? Should we not reply, ‘With submission, sir, and if there is no objection, I’d rather be cleaned first.’ ‘It may hurt, you know’ — ‘Even so, sir.’

I assume that the process of purification will normally involve suffering. Partly from tradition; partly because most real good that has been done me in this life has involved it. But I don’t think suffering is the purpose of the purgation. I can well believe that people neither much worse nor much better than I will suffer less than I or more . . . The treatment given will be the one required, whether it hurts little or much.

My favourite image on this matter comes from the dentist’s chair. I hope that when the tooth of life is drawn and I am ‘coming round,’ a voice will say, ‘Rinse your mouth out with this.’ This will be Purgatory. The rinsing may take longer than I can now imagine. The taste of this may be more fiery and astringent than my present sensibility could endure . . . ( Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1964, 107-109)

Thomas Howard

The hesitancy about prayers for the dead generally runs something like this: the dead are certainly beyond our reach, and their fate is now in God’s hands. It is inappropriate to pray for them, since their story is finished.

The reply might run like this: which of our requests, big or small, does not touch something beyond our reach? And where else but in God’s hands is the fate of anyone, living or dead?

The notion that a man’s whole story is finished at the precise point of physical death and his destiny fixed and sealed is not made clear in the Bible. The text, `. . . it is appointed unto man once to die, but after this the judgment,’ in Hebrews 9:27, which is often advanced in discussions on this point, tells us nothing more than what is obvious: we die once, and then begins the whole business of `judgment,’ whatever that may entail for every soul. The Bible does not vouchsafe us much light on how, much less when, our stories reach completion in the realm beyond death.

What the Church prays for in its prayers for the dead is twofold. First, it prays for the believing dead, that the work of grace begun in them in this life will go on until they reach `the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ’ (Eph 4:13). The Bible does not oblige us to think either that this work of grace halts in its tracks when physical death occurs or that it is suddenly rushed to miraculous completion . . . We deny death as an ultimate barrier.

Second, the Church prays for all the dead . . . They are still part of the huge fabric of Creation, and nothing in that fabric is beyond the scope of mercy. We cannot tell God what to do with them or speak with any certainty of what He is at any given point doing with them, but we can commend them to the mystery of His mercy, as we command all things thus. We must not be too hasty or fierce or cavalier in reaching conclusions about the judgment that Scripture spells out. God is the judge; we are priests, part of whose ministry is to offer prayer for all people. (Evangelical is Not Enough, Nashville: Nelson, 1984, 123-125)

Martin Scott

Many of us depart from this life not altogether saints and yet not altogether sinners. Moreover, some, who have been notoriously wicked repent at the last moment, and God has declared that He will not reject the penitent sinner. Such a penitent, although assured of God’s forgiveness, must nevertheless atone for his life-long transgressions. Unless there is a place beyond where atonement can be made, the death-bed penitent would entirely escape chastisement for sin. It is true that Christ forgave the sins of the thief on the cross, and also remitted the chastisement of them. He may do that with every sinner if He so wills. But that is not His ordinary way, as we know from Scripture. God forgave David his sin but chastised him dreadfully nevertheless. So, too, He punished Moses and others after He had pronounced forgiveness of their sins. We have, therefore, the fact that God is just and merciful, and also the fact that not all of us depart this life holy enough for companionship with God, and yet not wicked enough for perpetual banishment from His presence. Scripture declares that nothing defiled can enter heaven. They, therefore, who have lesser sins on their souls, or who have repented but not received chastisement in this life for their wickedness, must be made worthy of entrance into the all-holy presence of God in some place beyond this life. This is what is meant by Purgatory . . .

A patient of an incurable disease finds no solace in suffering, nothing but the dead weight of pain. But a patient who has the assurance of recovery willingly endures the surgeon’s knife or the unpleasant remedies of the physician. Purgatory is the vestibule of heaven. It is the certainty of eternal salvation. All its sufferings are inflicted in love and endured in love. It is because the souls in Purgatory love God so much that they suffer so much. In Purgatory they realize what God is, are drawn to Him most powerfully, and yet repelled from Him by the state of their souls. They cannot themselves hasten their union with God, since the time of meriting ends with life. But they can be helped by the charity of their friends on earth. By the communion of saints we on earth can offer to God our prayers, good works, alms-deeds and sacrifices of one kind and another, in their behalf. Above all, we may assist at the holy sacrifice of the Mass for them, and best of all we may have the holy sacrifice offered up especially for them . . .

God . . . shows His justice by requiring chastisement for wrong-doing, and His mercy by permitting us to go to the aid of those being chastised . . . (Things Catholics are Asked About, New York: P .J. Kenedy & Sons, 1927, 134-135, 141-142)

James Cardinal Gibbons

God ‘will render to every man according to his works,’ – to the pure and unsullied everlasting bliss; to the reprobate eternal damnation; to souls stained with minor faults a place of temporary purgation. I cannot recall any doctrine of the Christian religion more consoling to the human heart than the article of faith which teaches the efficacy of prayers for the faithful departed. It robs death of its sting. It encircles the chamber of mourning with a rainbow of hope It assuages the bitterness of our sorrow, and reconciles us to our loss. It keeps us in touch with the departed dead as correspondence keeps us in touch with the absent living. It preserves their memory fresh and green in our hearts. (The Faith of Our Fathers, New York: P. J. Kenedy & Sons, revised edition, 1917, 183-184)

Bertrand Conway

It is indeed strange that the Reformers should set aside such a body of testimony, both in Scripture and tradition, for Purgatory and prayers for the dead. But doctrine is so interwoven with doctrine in the consistent Gospel of Jesus Christ, that the denial of one central dogma logically means the denial of many others. Luther’s false theory of justification by faith alone led him to deny the distinction between mortal and venial sin, the fact of temporal punishment, the necessity of good works, the efficacy of indulgences, and the usefulness of prayers for the dead. If sin is not remitted, but only covered; if the `new man’ of the Gospel is Christ imputing His own justice to the still sinful man, it would indeed be useless to pray for the dead that they may be loosed from their sins. Luther’s denial of Purgatory implied either the cruel doctrine that the greater number of even devout Christians were lost, which accounts in some measure for the modern denial of eternal punishment, or the unwarranted assumption that God by `some sudden, magical change’ purifies the soul at the instant of death. (The Question Box, New York: Paulist Press, 1929, 395-396)

Karl Adam

The poor soul, having failed to make use of the easier and happier penance of this world, must now endure all the bitterness and all the dire penalties which are necessarily attached by the inviolable law of God’s justice to even the least sin, until she has tasted the wretchedness of sin to its dregs and has lost even the smallest attachment to it, until all that is fragmentary in her has attained completeness, in the perfection of the love of Christ. It is a long and painful process, `so as by fire.’ Is it real fire? We cannot tell; its true nature will certainly always remain hidden from us in this world. But we know this, that no penalty presses so hard upon the `poor souls’ as the consciousness that they are by their own fault long debarred from the blessed Vision of God. The more they are disengaged gradually in the whole compass of their being from their narrow selves, and the more freely and completely their hearts are opened to God, so much the more is the bitterness of their separation spiritualized and transfigured. It is home-sickness for their Father; and the further their purification proceeds, the more painfully are their souls scourged with its rods of fire . . .

Purgatory is only a thoroughfare to the Father, toilsome indeed and painful, but yet a thoroughfare, in which there is no standing still and which is illuminated by glad hope. For every step of the road brings the Father nearer. Purgatory is like the beginning of spring. Warm rays commence to fall on the hard soil and here and there awaken timid life . . . Countless souls are already awakening to the full day of eternal life . . . (The Spirit of Catholicism, translated by Justin McCann, revised edition, Garden City, New York: Doubleday Image, 1954 [orig. 1924], 110-111)

Servant of God John A. Hardon, S. J.

In spite of some popular notions to the contrary, the Church has never passed judgment as to whether purgatory is a place or in a determined space where the souls are cleansed. It simply understands the expression to mean the state or condition under which the faithful departed undergo purification . . .

The more something is desired, the more painful its absence, and the faithful departed intensely desire to possess God now that they are freed from temporal cares and no longer held down by the inertia of the body; they clearly see that their deprivation was personally blameworthy and might have been avoided if only they had prayed and done enough penance during life.

However, there is no comparison between this suffering and the pains of hell. It is temporary and therefore includes the assured hope of one day seeing the face of God; it is borne with patience, since the souls realize that purification is necessary, and they do not wish to have it otherwise; and it is accepted generously, out of love for God and with perfect submission to his will . . .

Parallel with their sufferings, the souls also experience intense spiritual joy . . . There are many reasons for this happiness. The souls are absolutely sure of their salvation. They have faith, hope, and great charity. They know themselves to be in divine friendship, confirmed in grace, and no longer able to offend God.

Although the souls in purgatory cannot merit, since they are no longer in the state of wayfarers, they are able to pray and obtain the fruit of prayer. Moreover, the efficacy of their prayers depends on their sanctity. This means that most probably they can obtain a relaxation of their own (certainly of other souls’) sufferings. They do this not directly but indirectly in obtaining from God the favor that people might pray for them and that suffrages made by the faithful might be applied to them.

However, it is not probable but certain that they can pray and obtain blessings for those living on earth. They are united, as the Second Vatican Council teaches, with the pilgrim Church in the Communion of Saints. We are therefore encouraged to invoke their aid, with the confidence of being heard by those who understand our needs so well from their own experience and who are grateful for the prayers and sacrifices we offer on their behalf. (The Catholic Catechism, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1975, 274-275, 278-280)

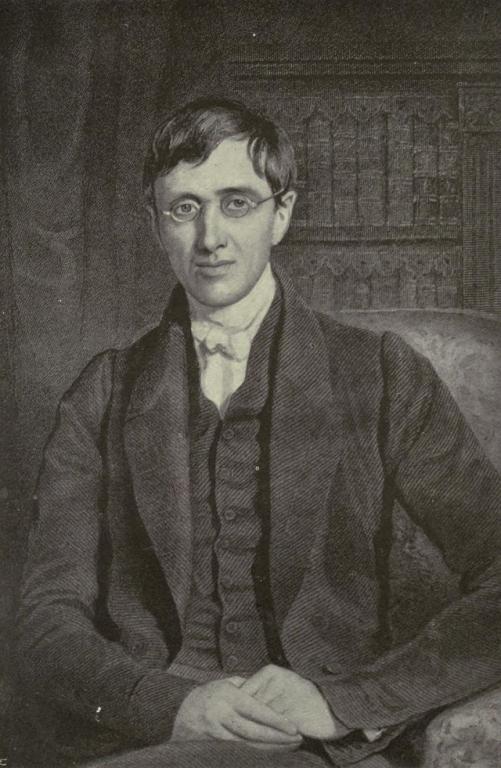

Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman

In one sense, all Christians die with their work unfinished. Let them have chastened themselves all their lives long, and lived in faith and obedience, yet still there is much in them unsubdued, – much pride, much ignorance, much unrepented, unknown sin, much inconsistency, much irregularity in prayer, much lightness and frivolity of thought. Who can tell, then, but, in God’s mercy, the time of waiting between death and Christ’s coming, may be profitable to those who have been His true servants here, as a time of maturing that fruit of grace, but partly formed in them in this life – a school-time of contemplation, as this world is a discipline of active service? Such, surely, is the force of the Apostle’s words, that `He that hath begun a good work in us, will perform it until the day of Jesus Christ,’ until, not at, not stopping it with death, but carrying it on to the Resurrection. And this, which will be accorded to all Saints, will be profitable to each in proportion to the degree of holiness in which he dies . . .

It will be found, on the whole, that death is not the object put forward in Scripture for hope to rest upon, but the coming of Christ, as if the interval between death and His coming was by no means to be omitted in the process of our preparation for heaven. (Parochial and Plain Sermons, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1987 [originally 1843, during Newman’s Anglican period], 715-716; Sermon: “The Intermediate State,” 1836)

***

(originally 1994)

Photo credit: Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890); portrait by William Charles Ross (1794-1860) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***