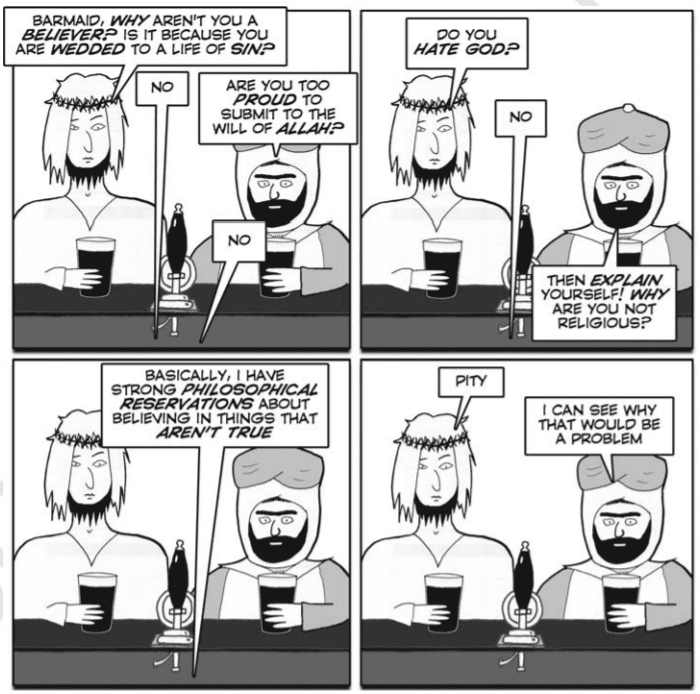

I have just had this levelled against me:

I rather doubt there is such a thing as atheism. When atheism manifests itself, it appears to be no more than a mixture of confusion and father issues. Most professed atheists seem to live as if there is a god, despite their rejection of him, and a great many expend a great deal of anger towards this thing they claim does not exist. This is probably why you can’t draw them in on an argument. No matter what you say, they’re fighting with their fathers and they’re going to stay out later after curfew no matter what the old man says: “Hey, screw you Dad!” is what you get.

To which another interlocutor, Guy, (both of these commenters have featured in articles here though don’t comment here) opined in obsequious agreement:

perfect – a straw God easily dispensed with and knocked over with a feather. Never a willingness to posit what a real omniscient and omnipotent God *would* be (whether he exists or not) and how absurd his creatures making demands that he ‘prove’ his existence to them would also be. Basically it’s a prejudice that never honestly entertains a question it affects to be examining. It’s just the imposition of a prejudice as opposed to an honest examination of an issue.

The first commenter was the person who claims Christians are the most persecuted. A very simple assertion that took me a big old article to analyse and debunk. I claimed his point about fatherhood was a really common myth about atheists that it didn’t really warrant a response. He then stated:

But if the point I make is as tired and commonplace as you say, it would be very easy for you to bring up a CONCISE and satisfactory response to it.

Okay, what annoys me about climate denial, science denial, bald assertions, Trump’s lies, lies in general, is that they are very easy to say and one can be very concise. But just because you can state them concisely, it doesn’t mean you can unpick them concisely. Indeed, this is precisely the gripe. It takes so much more effort to build than to destroy, to build up cases using evidence and robust methodology than to destroy such edifices with lies and bald assertions.

This is the big shame about skepticism: it requires far more effort to be right than it does to be wrong.

The annoying thing is the burden of proof should be on the claimant. So, here, I should demand robust argumentation and evidence from him to support his initial claims. Instead, I come here to put down my thoughts in greater detail. More fool me. More fool me for even engaging with such silly comments.

Hey ho. Here goes. Slightly out of order:

The denial of God and anger at him

Most professed atheists seem to live as if there is a god, despite their rejection of him, and a great many expend a great deal of anger towards this thing they claim does not exist. This is probably why you can’t draw them in on an argument.

Russell Blackford (with whom I used to blog), a few years back, wrote a super book “50 Great Myths About Atheism” with Udo Schuklenk because they got tired of the same old naive assertions made by theists. Three of the chapters are pertinent to this:

Myth 3 Atheists Believe in God but are in Denial 14

Myth 5 Atheists Hate or are Angry with God 21

Myth 6 Atheism is a Rebellion Against God’s Authority 24

These chapters are well worth reading and put these sorts of claims to bed.

Michael Martin wrote a 1996 response (“Are There Really No Atheists?“) to Van Til, who in 1969 claimed there were no atheists (as well as greg Bahnsen). Go read it.

Part of the problem is the phraseology here with the commenter. It is a straw man. Indeed, most of that thread is an army of straw men. Let’s fix the statement:

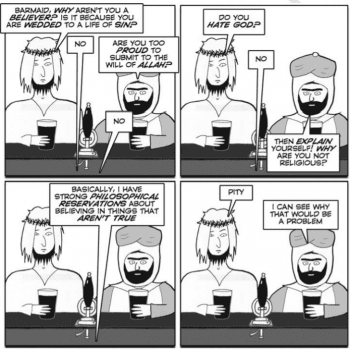

Most professed atheists live as if there is no god, including in their rational rejection of the idea of it or arguments presented for its existence.

Part of the problem with arguments of God is the gendered pronoun usage. God is best described as an “it” (I often make this point by calling God she). This possibly underwrites the erropneous claims that come later concerning the rejections of father-figures.

Back to the denial of God issue – I think the commenter needs to be more specific here in exactly what he means (Martin sets out two interpretations in his refutation – the strong and weak theses). This simply appears not to apply to any atheist I know, As for being angry with God, we literally can’t be angry with something we genuinely think does not exist.

It’s a clever ruse that ends up being an unfalsifiable claim. When I provided some atheists, such as Blackford, in defence of the original accusations made, Guy stated: “By appeal to people who reject theism, comically”. So I cannot use atheists to defend atheism? Because not only is this an insane argument, it can be used to invalidate defences of theism by theists, too. Oh dear.

I am just wondering, though, can we claim that Christians hate Muslims on account of the same logic? Do they then have tacit admission that Allah exists? How about Zeus, or…or…?

As Blackford states (p.21-22):

It might suit Jensen and like-minded religious figureheads if we were not sincere or serious in our view that God does not exist. Robert T. Lee is one critic of atheists who makes this quite explicit. He argues that atheists ‘‘think since they deny the existence of God, they cannot hate Him. But it’s really the other way around: they know He exists, that’s why they hate Him’’ (Lee, 2004). It goes without saying, perhaps, that this kind of logic is question-begging. From an atheistic viewpoint, the various gods worshiped by Christians and others are essentially fictional or mythological characters. Why hate them?

Of course, that does not prevent atheists from viewing the Abrahamic God, as depicted for example in various books of the Bible, as a most unattractive character. It is easy to see this being as loving vengeance and warfare, as being prurient in its obsession with matters of sex, and as especially repulsive in its demands for endless praise and worship and in its requirement of blood sacrifice before forgiving sins. For that reason, many atheists are glad not to live in a world that contains this being. Such a world is clearly not the same as one created and ruled by a truly benevolent deity. Unfortunately, we appear not to be living in that world either.

Thus there is a religious cottage industry devoted to explaining (away) the evil that exists in our world despite the presence of a benevolent God, who supposedly created it. Theologians call this the theodicy problem (often referred to as the problem of evil). How can it be that there is so much evil existing in a world they believe has been created by an all-powerful, all-knowing, and benevolent deity? The obvious answer is that there simply is no such deity.

Atheists tend to find the religious answers to such questions contrived or unsatisfying. That is not, however, the same as hating an actual being – God. Nor do atheists tend to hate historical or legendary figures, such as Jesus, any more than other such figures about whom little is known with certainty. Some atheists are critical of the moral character of Jesus as depicted in the traditionally accepted Gospels (e.g., Tooley, 2009), but that should not be confused with hatred. More generally, there is a tendency for religious apologists to blur the distinction between harsh criticism and expressions of hatred.

For example, Alister McGrath comments, not exactly in a charitable spirit, on Richard Dawkins: ‘‘Dawkins preaches to his god-hating choirs, who are clearly expected to relish his rhetorical salvoes, and raise their hands in adulation’’ (McGrath and Collicutt McGrath, 2007, p. x).

I could quote the whole chapter, but expediency, right?

However, I will leave you with some, er, data. You know, actual evidence. Blackford, again:

Interestingly, and not surprisingly perhaps, surveys suggest that religious believers are often angry with the God they believe in. A study undertaken by Julie Exline and colleagues found that between one-third and two-thirds of religious people surveyed in the USA conceded being angry with their respective gods. The reason most frequently mentioned is that they feel let down by God, usually in the aftermath of a major health scare or other personal tragedy that he did not prevent (Exline et al., 2011).

When atheism manifests itself, it appears to be no more than a mixture of confusion and father issues.

“I know you are, you said you, but what am I?”

We have two forms of atheism: strong atheism and weak atheism. Let’s start with weak atheism – a lack of belief in a god or gods. You can’t really get clearer than that – a belief you just don’t have. But with either position, as with all positions, it is about several things: psychology and rational argument. I agree that psychology is always at play when we come to bel;ieve things, I just disagree that the psychology here involves the rejection of a father. Either way, the pyschology does not invalidate the rational arguments, even if it can, with post hoc rationalisaiton, involve the scrabbling around for those arguments to defend an intuitively-taken position.

I accuse many Christians and right-wing commenters of doing that here (see the endless discussions on the Second Amendment, conceptual nominalism and natural rights).

When it comes to rational argument, atheists really are clear. It might revolve around the problem of evil, or the inherent contradictions and confusions in arguing for OmniGod under classical theism, or the nonsenses of the Kalam Cosmological Argument. The clarity is there. There is no confusion. I am very clear: I am Certain of My Atheism. I’ve Said All I have to Say. Or Have I?

The confusion from theists comes from a top-down appraoch. Rather than buil;ding to a conclusion, they start with God and the Bible and attemt to build backwards. It’s a messay and very, very confused affair. Heck, christian theologians the world over disagree with their theologies. Thoedicies abound. So no, I would certainly posit, instead, that theism is far more confused. Necessarily so. Here is the huge hypocrisy.

When you have to apply an ancient, parochial book to history, science and philosophy, the mental contractions and rational gerrymandering you have to do is quite astounding. It is even why I have argued previously that presuppositionalist biblical literalists are far more logically consistent than almost all Christian theists of the modern, more liberal UK persuasion, even if their starting premises are broken. Trying to allow a liberal understanding of, say, homosexuality to jibe with the Bible and theology is embarrassing to watch, at times.

See my segment in the Skepticule podcast episode 51 for more details on this: Counter-apologetics on Original Sin, Adam and Eve, the Westboro Baptist Church etc available now! (I thought I’d written an article on it – turns out that will be my next piece).

Those father issues

No matter what you say, they’re fighting with their fathers and they’re going to stay out later after curfew no matter what the old man says: “Hey, screw you Dad!” is what you get.

As Blackford again opines, this issue is one that has been around for some time. At the beginning of his chapter “Myth 6 Atheism Is a Rebellion against God’s Authority”, he refers to the seminal work of George Smith (p.24):

As George H. Smith mentions, atheists are often accused of being in some sort of neurotic rebellion, especially if the atheist concerned is young. Smith notes, however, that atheists cannot win once this approach is taken – a middle-aged atheist can be accused of such things as ‘‘the frustration of daily routine, the bitterness of failure, or… alienation from oneself and one’s fellow man.’’ If the atheist is old, the accusation can relate to ‘‘the disillusionment, cynicism and loneliness that sometimes accompany one’s later years’’ (Smith, 1979, p. 24). All of this is question-begging since neither youth nor old age is evidence of any kind of neurotic response to the God question. Speculations about states of mind get us nowhere.

Indeed, as Smith himself says in Atheism – The Case Against God (p.19):

Contrary to what many theists like to believe, atheism is not a form of neurotic rebellion or mental illness. The religionist cannot rid the world of atheists by committing them to an isolated asylum where they can be ignored. To label atheism as a psychological problem is a feeble, almost laughable attempt to evade the fundamental questions of truth and falsity. Is theism true? What reasons are there for believing in a god? These are the important issues, and these are the issues to which the theist must address himself if he wishes to confront the challenge of atheism.

(There is further discussion on p.160 of this.)

It’s not that God represents an authoritarian father-figure that all, every single one of us atheists have had some issue with, it’s that God is a parochial and outdated invention with parochial and outdated moral strictures.

For many of us, the moral norms advocated by morally conservative theists do not look like the edicts of a superlatively wise and benevolent being, but more like relics from a less enlightened era. At best, some of them may have made sense as standards of behavior in earlier social circumstances, even though they make little or no sense now. Once we reach that point, holy books, traditional teachings, and official pronouncements from religious organizations appear unlikely to be divinely inspired. That, in turn, casts doubt on their authority in other matters such as claims about the existence and character of supernatural beings. (p.26)

Perhaps he is referring to the nonsense that is Paul Vitz’s Faith and the Fatherless, but I don’t think so: this isn’t about absentee fathers, but about reacting, psychologically, to some kind of authoritarian father-figure rooted in somehow in the atheists’ experiences. Perhaps, then, it is taking the thesis of James Spiegel in his The Making of an Atheist: How Immorality Leads to Unbelief. You would hope not, as this is a book and thesis that atheists have taken serious issue with (by all accounts it’s drivel). He makes such claims as:

We may summarize the biblical diagnosis of atheism as follows. The atheists’ problem is rebellion against the plain truth of God, as clearly revealed in nature. This rebellion is prompted by a morality, which diminishes understanding, and a genuine ignorance results. This is not a loss of intelligence so much as a selective intellectual obtuseness or imperviousness to truths related to God, ethics, and human nature. But the root of this obtuseness is moral in nature.

It follows from the biblical diagnosis that atheists’ arguments are an intellectual ruse masking their rebellion. The recent spate of new atheist books, like the entire history of atheistic publications, amounts to little more than a literary subterfuge. The flaws in their arguments are easily exposed – whether matters of bad logic or faulty presuppositions. These are further symptoms of their wilful disbelief, which takes both this active form (presenting atheistic arguments) and the passive form of ignoring the myriad evidences for God, to which Paul briefly refers and which atheist apologists, from Plato and Aquinas to CS Lewis and Peter Kreeft have tirelessly illuminated. (p.56)

Holy moly. This is just nonsense. I wouldn’t take this seriously in any form, and yet Spiegel seems to be one of the main “rebellion against God as father” proponents. Sadly, his case is built largely around biblical exegesis rather than any serious psychology. And to think that somehow Thomists and CS Lewis and Kreeft have somehow closed the book (when Thomism is arguably at loggerheads with other theologies) is village theism.

Thus, the choice of the atheistic paradigm is motivated by non-rational factors, some of which are psychological and some of which are moral in nature.

The hardening of the atheistic mind-set occurs through cognitive malfunction due to two principal causes. First, atheists suffer from paradigm-induced blindness, as their worldview inhibits their ability to recognize the reality of God that is manifest in creation. Second, atheists suffer from damage to the sensus divinitatis, so their natural awareness of God is severely impeded. (p.114)

I just don’t know where to start with the sheer hypocrisy of this last quote. If my interlocutor wants to take these arguments seriously, have at it. they are laughable assertions.

So, really, this goes back to supposedly rebelling against God’s authority as if we just don’t like those house rules that God has imposed, that we staying out beyond curfew.

Or is it that, in God’s house, you get executed for being gay, stoned for adultery (in the Portsmouth Diocese, on the decree of the Diocese, our primary schools were responsible for teaching that moral edict to Year 1 children when I worked in faith schooling – 6 year-olds), that slaves are okay knocking about the house, being dehumanised, so on and so forth. And if we go to war, it’s okay to rape enemy families.

From my own experience, I have no issue with my father in this way. Despite the fact that he, as well as my interlocutor, voted Brexit, the gay relatives I have are safe in his house, and he doesn’t keep slaves. We might disagree a lot on politics right now (a very recent thing), but he and my mother live around the corner and we’re just fine, thank you very much,

But no, me rejecting God is definitely because I just want to rebel: “Aw, Dad! C’mon! Please, do I have to murder my mixed-race neighbours to keep God’s people pure?!” (Numbers 25:6-13)

I mean, these ten biblical passages I reject solely on account of mere father-figure rebellion (Dan Barker’s list), right?

10. God destroys a good family ‘for no reason.’

(Job 2:3 New Revised Standard Bible)

9. God destroys the fetuses of those who do not worship him.

(Hosea 13:4, 9, 16 New International Version)

8. God approves the massacre of a peaceful people so one of his tribes could have a place to live.

(Judges 18:1–28 NIV)

7. Babies are slaughtered and wives raped.

(Isaiah 13:9–16 NIV)

6. A mixed-race couple is murdered by a godly priest to keep God’s people pure.

The righteous priest Phinehas murdered a loving couple for the crime of miscegenation. Then he was praised by God and rewarded for the hate crime with a perpetual priesthood for keeping the nation racially pure.

(Numbers 25:6–13 NRSV)

5. A daughter is burned as an acceptable sacrifice to God.

(Judges 11:30–39 NIV)

4. The cannibalistic God makes people eat human flesh.

(Leviticus 26:27–29 King James Version)

3. God threatens rape, then takes credit for it.

(Jeremiah 13:15–26 NRSV)

2. God threatens sexual molestation.

(Isaiah 3:16–17 KJV)

1. God wants you to be happy to dash babies against the rocks.

(Psalm 137:8–9 NRSV)

Finally…

Let me return to Guy’s point:

perfect – a straw God easily dispensed with and knocked over with a feather. Never a willingness to posit what a real omniscient and omnipotent God *would* be (whether he exists or not) and how absurd his creatures making demands that he ‘prove’ his existence to them would also be. Basically it’s a prejudice that never honestly entertains a question it affects to be examining. It’s just the imposition of a prejudice as opposed to an honest examination of an issue.

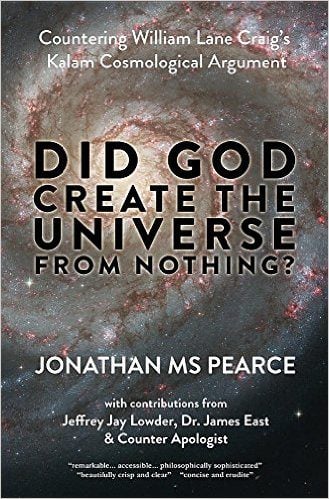

Well, I have written an ebook on entirely this problem. It’s not a straw man, it’s classical theism.

The Problem of “God”: Classical Theism under the Spotlight (UK). He’s welcome to read it. At any rate, we’re not asking that “he” (God) proves “he” exists, we ask his followers prove it, the god-entity, exists, or at least provide compelling enough arguments, just as they would ask of Muslims, climate change, unicorns, UFOs, etc.

What’s good for the goose, and all that.

Essentially, silly rhetorical nonsense.

Stay in touch! Like A Tippling Philosopher on Facebook: