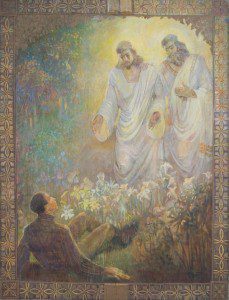

Sometime around the year 1820, the young Joseph Smith was troubled. According to the earliest account, written in 1832, Smith was anxious over the state of his sinful soul. He “felt to mourn,” for his own sinfulness and that of the world. He was convinced of God’s existence, simply by looking at the wonders of nature that surrounded him. This account does not state where Smith prayed, only that he “cried unto the Lord for mercy … in the wilderness.” The Lord answered Joseph’s prayer. “A piller of fire light above the brightness of the sun at noon day come down from above and rested upon me.”

In what became the canonical account of Joseph Smith’s history for Latter-day Saints, about six years later Smith recalled that he was troubled, not primarily by the state of his own soul, but by the pluralistic religious discord of the early American republic. Smith determined to ask God which of the churches was true. This 1838/1839 account specifies that he “retired to the woods to make the attempt” in the Spring of 1820. After an evil power enveloped him in darkness, Smith recalled, “I saw a pillar of light exactly over my head above the brightness of the sun, which descended gradually until it fell upon me.”

Smith found that no one (apparently outside his small circle of family and friends) believed his vision. “However it was nevertheless a fact,” he stated, “that I had had a Vision.” He compared himself to “Paul … when he made his defence before King Agrippa and related the account of the Vision he had when he saw a light and heard a voice.”

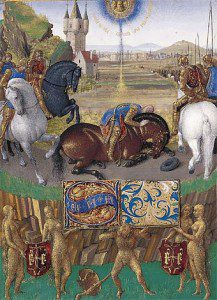

In Acts 26, Paul relates his road-to-Damascus conversion to Agrippa: “At midday, O king, I saw in the way a light from heaven, above the brightness of the sun, shining round about me and them which journeyed with me.” Paul and his companions fell to the ground.

Biblical narratives for centuries have shaped the way that Christians see and hear their Savior. This was certainly the case in Joseph Smith’s day. Visions of Jesus often came accompanied by light “above the brightness of the sun,” a phrase familiar to American Christians from the King James Bible. For example, a short time after his conversion, Charles Finney found himself nearly knocked to the ground by a “light like the brightness of the sun.” Finney interpreted the light as the “glory of God.” According to Richard Bushman’s Rough Stone Rolling, a Universalist minister who in 1825 spent several months preaching at the Palmyra Academy, once dreamed of Christ descending heaven “in a glare of brightness, exceeding ten fold the brilliancy of the meridian Sun.” Visions of God had long been associated with fire and light, as was the case in the visions of Moses and Ezekiel. This was still true eighteen hundred years later. Visions of God and Jesus Christ typically correspond to the way that believers have already imagined the divine, imaginations often shaped by biblical narratives (and artwork and prior visions, one imagines).

If not as pervasively visionary as the Hebrew scriptures, the New Testament contains several accounts of visions, culminating with the revelation of John of Patmos. The Holy Spirit appears in the form of a dove at Jesus’s baptism. In Luke’s gospel, the women at the tomb see a “vision” of angels (in the other synoptic gospels, the angels are simply there). Some Christians have considered the appearance of Elijah and Moses on the high mountain a vision. The Book of Acts contains several significant visions, including Paul’s encounter with the Lord en route to Damasus. In the tenth chapter of Acts, Cornelius “saw clearly in a vision an angel of God” who instructs him to visit Peter. The next day, Peter falls into a trance, sees heaven open, and receives a vision of all sorts of birds, animals, and reptiles.

Paul refers to visionary experiences in several of his epistles, most interestingly in the second letter to the church at Corinth, in which he feels compelled to “boast” of visions and revelations in order to counter the boasting of his rivals. In all likelihood referring to himself, Paul speaks of a man who fourteen years earlier was “caught up to the third heaven.” He is uncertain whether he went there “in the body or out of the body,” in other words whether he was physically transported or simply gifted with a vision. Paul does not reveal the details of what he saw and heard, only to saw that “he heard things that cannot be told, which man may not utter.” The notion of a “third heaven” is an interesting detail, as is Paul’s claim to an undetermined number of “visions and revelations.”

The revelation par excellence of the New Testament comes in what was its most disputed book. John, on the island of Patmos, was “in the Spirit on the Lord’s day” and receives instructions to write what he sees in a book. What he sees is deeply shaped by more ancient visions of a figure “like a son of man,” a term frequently used in Ezekiel to refer to its author. In Daniel, “one like a son of man” comes “with the clouds of heaven” and is given “dominion and glory and kingdom” by “the Ancient of Days.” John of Patmos identifies “the son of man” as Jesus Christ and describes him with language partly taken from both Daniel and Ezekiel. As in Daniel, John’s “son of man” has flaming eyes, body parts of bronze.” As in Ezekiel, John hears “the sound of many waters.”

Next week’s post will discuss the significance of John’s visions for early Christians. What interests me here is how visions shape future visions. Ezekiel and Daniel very much shaped the way that John of Patmos saw God. John’s visions, in turn, have shaped two millennia of Christian visions of Jesus, both in terms of what visionaries saw and what they heard. Paul’s visionary experience shaped the way that subsequent Christians encountered Jesus Christ, in a blaze of light and glory “above the brightness of the sun.”