Should Christians have any particular care about food and eating?

Should Christians have any particular care about how women give birth?

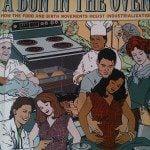

Those paired questions may not seem natural to treat together. Barbara Katz Rothman, though not addressing a religious angle, joins concerns about food and childbirth in her wittily titled new book, A Bun in the Oven. The very title seems to predetermine her audience–a book about food and babies must aim for female readership, no?–but at once tweaks expectations. As the author insists, neither topic is just about private preferences or gendered choices. Rothman, sociologist at the City University of New York, with a distinguished career studying birth practices and advocating midwifery, more recently became interested in the social context of food. Not just what we eat but where it comes from, how it is processed and sold, how it gets tagged with status markers, how small personal decisions about eating (which cereal to pour in my bowl this morning?) get made against the backdrop of mass-scale production, with each bite bearing broad consequences. Her wit is to put the two social problems (and movements) together. As the subtitle promises, she is interested in “How the Food and Birth Movements Resist Industrialization.”

In full-blown Dickensian idiom, Rothman opens this way:

For both of these movements, one could say it is the best of times and it is the worst of times. It is the age of wisdom, it is the age of foolishness, it is the age of organic kale chips, it is the age of McDonald’s, it is the epoch of belief, it is the epoch of incredulity, it is the moment of the unattended water birth, it is the moment of the elective cesarean section, it is the season of light, it is the season of darkness, it is the time of the rising star of the master chef, it is the time of ubiquitous processed corn, it is the spring of hope, it is the winter of despair.

She’s right. We are in a strange moment, in terms of the way we eat and the ways babies come to be. The book, perhaps regrettably, is not actually the tale of two social movements, not equally about food reform and birth reform. Rothman’s task turns out not to be equal time in a comparative study of the two phenomena, but reevaluation of the birth movement through comparative perspective. Since Rothman notices “foodies” seem to be having more success than “birthies,” what can each learn from the other?

Rothman argues that both movements at base address the same problem: the submission of an important feature of human life to the imperatives of industrialization. Along with industrialization come the glamorizing of “science” as a determinant of expertise and progress, and a new calculus of risk misapplied to denigrate human goods resistant to efficiency and uniformity. In food, that means crops developed for sameness and shelf stability rather than for flavor or nutrients, grown by methods that minimize the skills of farmers and cooks; processing that harms the environment and wastes nutrients; marketing that tempts eaters to overdo salt, sugar, and fat and thereby worsens public health. Food systems are a big problem, affecting many, not just a little problem, and certainly not just the dainty pique of elites fussing over local lettuce. Poor people are likelier than rich people to suffer bad effects of problematic food production and consumption.

Those same industrializing trends affect birth, Rothman explains. The way hospitals calculate birth risk makes the healthy look pathological. Worse, she further maintains, it makes us forget what normal birth should be. Positioning doctors as primary authorities over childbirth devalues other ways of handling this experience and undercuts the skill of other practitioners, particularly midwives. Rothman’s advocacy for midwifery aims not first to maximize choice but to respect the skill of women practicing this craft. Midwives bring important knowledge and experience to births. Situating most births in hospitals invites unnecessary intervention and can disengage the woman from her own action in bringing forth a baby. The high incidence of cesarean section, now used in about about third of American births, is the most telling evidence of the trends that Rothman traces. Subjecting birth to industrial processes, like subjecting food to extrusion, instantization, pressurization, and chemical preservations, is neither the best nor safest way of handling this important feature of human life.

Why does this matter? It should be obvious why food matters. We all eat; most of us want to eat well. Many of us even practice eating with gratitude, gratitude not only to an ultimate source of our nourishment but to those who grow, deliver, and cook it. That gratitude should activate care for how these things are done and for the people who do them. It seems not very hard to see why food invites religious reflection. The Bible makes many pronouncements about food and eating. Religiously inspired judgments about food thread through the experience of American Christians too, from Puritan declarations of public fasts through nineteenth-century projects construing temperance and hygiene as devotional disciplines, to more recent writings on what we eat, the spirit of food and its social and sacramental dimensions.

It seems to me no less obvious why birth matters. Acknowledging appropriately the significance of birth may not oblige us to elevate one system over the other, home or hospital, doctor or midwife, though Rothman thinks it does. Rothman contends that midwifery is as safe if not safer than OB-in-hospital deliveries, with birth data to prove it. Birth attended by a midwife, especially birth in a home, might be not only more attentive to the particular woman’s situation, the timing of labor, the strategies appropriate to minimize pain, the push-pull of interactions with others interested in the birth, but can also deal more effectively with complications. Pressing the patient’s case into a hospital-standard rule does this less well. Some Christian communities, particularly the Amish, advocate midwifery and home settings for Christian childbirth for reasons not far from Rothman’s, with religious and risk-driven concerns. As Rothman’s argument encourages readers to consider how best to honor woman, family, and baby during the coming of new life, the midwifery model has much to recommend it. How to honor that event should figure into our decisions about systems that help women welcome babies, not only our own, but how women with fewer options and less money, more constraints and hardships, are enabled to welcome theirs.