Today Union Theological Seminary concludes its annual lecture series in honor of one of its most distinguished former students, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was executed in a Nazi concentration camp 72 years ago tomorrow. Coinciding as it does with the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, this particular installment of the Bonhoeffer Lectures is entitled “Re-Forming the Church of the Future: Bonhoeffer, Luther, Public Ethics.”

Today Union Theological Seminary concludes its annual lecture series in honor of one of its most distinguished former students, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was executed in a Nazi concentration camp 72 years ago tomorrow. Coinciding as it does with the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, this particular installment of the Bonhoeffer Lectures is entitled “Re-Forming the Church of the Future: Bonhoeffer, Luther, Public Ethics.”

Yesterday’s sessions featured a stellar line-up of historians, including Carlos Eire (“The Protestant Reformation Legacy through Catholic Eyes”), Hartmut Lehmann (“Fatal Coincidences 1933: Nazism’s Triumph and Luther’s 450th Birthday”), and Victoria Barnett (“Looking for Luther: 1933-1939”), who is general editor of the English translation of Bonhoeffer’s works. Today looks more to the future of the church, with the speakers including South African theologian Allen Boesak (“Church, Racism and Resistance — Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Critical Dimension of Theological Integrity”).

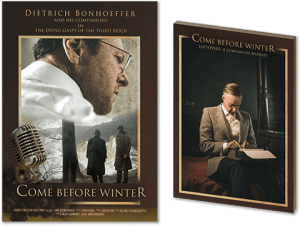

I’m not sure whether or not you’ll be able to watch or listen to recordings of those talks, or if they’ll be published. But I do know that you can watch the new Bonhoeffer movie that is being screened at Union as part of the lectures, Come Before Winter.

Directed by Kevin Ekvall and written by Hellmut Schlingensiepen, Come Before Winter was the brain child of producer Gary Blount, a psychiatrist here in St. Paul, Minnesota whose fascination with Bonhoeffer grew after watching Martin Doblmeier’s 2003 documentary.

Directed by Kevin Ekvall and written by Hellmut Schlingensiepen, Come Before Winter was the brain child of producer Gary Blount, a psychiatrist here in St. Paul, Minnesota whose fascination with Bonhoeffer grew after watching Martin Doblmeier’s 2003 documentary.

(Full disclosure: Blount is the stepfather of my colleague Amy Poppinga, interviewed here in January. She has a small part in the film.)

In an interview with Spectrum, a Seventh-day Adventist magazine, Blount explained the focus of the film:

Our story is about the final chapter in Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s life and what must have been the aching for deliverance by the Allies, who were rapidly closing in. We felt our time frame might extract something of the essence of his life and the perspective which he seemed to seek — “the view from below.” This view now includes more uncertainty, wartime cruelty, and vengeance.

Bonhoeffer had long been an outspoken foe of Hitler, and we chose to tell the story with the help of a couple of other anti-Nazis: seriously broken vessels Sefton Delmer and Otto John. The latter has been called “the living link” between Bonhoeffer’s last days and the storyteller in England.

Like Bonhoeffer, John was connected to conspiracies against Hitler, but he escaped to Britain, where he worked on “black propaganda” operations alongside Delmer and future James Bond creator Ian Fleming. While this story becomes the framing device for the film, I invariably found myself waiting for those scenes to end. For the film is predictably more compelling when it focuses on Bonhoeffer (played by Argentine-American actor Gus Lynch). Some scenes are shot on location in Berlin, the former sites of the Buchenwald and Flossenbürg camps, and the island of Rügen, where Bonhoeffer had a long conversation with fellow anti-Nazi resister Helmuth James von Moltke in April 1942. (Moltke was also executed before war’s end, in January 1945.)

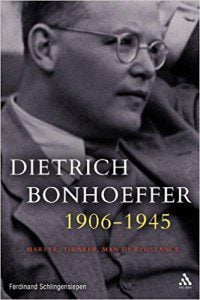

Even more valuable are the film’s interviews with leading Bonhoeffer scholars, including European experts like Schlingensiepen’s father, Ferdinand. In this country, at least, his Bonhoeffer biography was overshadowed by those written by Charles Marsh and Eric Metaxas, both of which Ferdinand Schlingensiepen has criticized for wrenching the German martyr out of his historical and theological context:

Even more valuable are the film’s interviews with leading Bonhoeffer scholars, including European experts like Schlingensiepen’s father, Ferdinand. In this country, at least, his Bonhoeffer biography was overshadowed by those written by Charles Marsh and Eric Metaxas, both of which Ferdinand Schlingensiepen has criticized for wrenching the German martyr out of his historical and theological context:

Marsh and Metaxas have dragged Bonhoeffer into cultural and political disputes that belong in a U.S. context. The issues did not present themselves in the same way in Germany in Bonhoeffer’s time, and the way they are debated in Germany today differs greatly from that in the States. Metaxas has focused on the fight between right and left in the United States and has made Bonhoeffer into a likeable arch-conservative without theological insights and convictions of his own; Marsh concentrates on the conflict between the Conservatives and the gay rights’ movement. Both approaches are equally misguided and are used to make Bonhoeffer interesting and relevant to American society. Bonhoeffer does not need this and it certainly distorts the facts.

[UPDATE, 4/10: Please note that I’ve rethought my decision to include this quotation, at least without a bit of critical response. I did write it this way and so will leave it in the post, but please read my follow-up if you’re taken aback by the claim that Metaxas’ and Marsh’s treatments of Bonhoeffer are “equally misguided.”]

By contrast, says historian Kyle Jantzen, Schlingensiepen’s Bonhoeffer’s “combination of curiosity, moral courage, and theological creativity makes him so utterly unpredictable, so full of paradoxes (perhaps even contradictions), and so impossible to pigeonhole.”

If you’re interested in seeing Come Before Winter, you can buy the DVD here, or arrange for a screening at your church or college using this form.