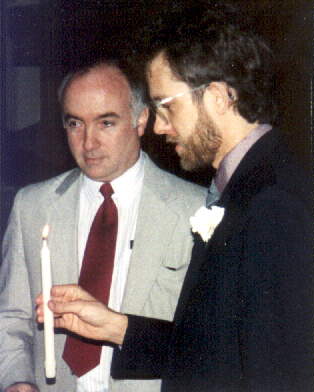

My very good friend John McAlpine (left), sponsoring my reception into the Catholic Church on 8 February 1991. He had the most personal influence in my conversion.

***

[transcribed on 12 January 1999, from the radio interview of 8 September 1997]

***

Al Kresta, talk show host (more info. below), is also the author of Why Do Catholics Genuflect? (2002), Why Are Catholics So Concerned About Sin? (2005), and Dangers to the Faith (2012).

*****

Introduction

I consider myself (in apologetic matters) primarily a writer. That being the case, I haven’t done much public speaking. On a few occasions, however, I was persuaded to venture out into the “oratorical world.” I was interested in these particular opportunities because they were largely conversational in nature, which is my personal preference, as opposed to a straight lecture format. Talking is quite distinct from writing, and one who has read some of my papers may note that my style is markedly different as well. I’m much more formal and rigidly logical and systematic in my writing. The following exchange gives an indication of what I am like when I sit down to talk to my Christian friends and fellow apologists, or to a non-believer. I’ve been told that I am perceived as a much gentler, tolerant, friendly soul in person, compared to the impression some get from my writing! I find that fascinating; I would hope that my writing does not come across as uncharitable at all. I do find most apologists to be genuinely nice people — contrary to what the stereotype may be.

The following is a transcript of the only spoken version of my conversion story, which presents several details and perspectives not included in my two written accounts. I was interviewed in studio by my longtime friend and former pastor Al Kresta (his words are in blue), on his Catholic talk radio program Al Kresta Live, on WDEO-AM, from Ann Arbor, Michigan (now called Kresta in the Afternoon, and able to be heard on local Catholic radio or on the Internet). His story of his own return to the Church was also included in Surprised by Truth, right after mine: the last one of the book. Al’s previous endeavor on WMUZ-FM, Talk From the Heart, was one of the most popular and influential evangelical Protestant talk shows in the country, from 1987 to 1997. I have also transcribed his own marvelous story of coming back to the Church. The interview was approximately 25 minutes long. The audio version can be downloaded for free on my own e-booksite.

**********

You’re listening to Al Kresta Live. With me right now: Dave Armstrong, Catholic apologist and free-lance writer. Dave is also a longtime friend, and I think [he] has one of the best websites out there, if you’re interested in the biblical evidence for Catholicism. Dave, good to have you here.

Great to be here, Al!

We wanted to talk about your story; how you came to know Jesus, and how you came to recognize His Church. It’s contained in the volume Surprised by Truth. So, take us to the beginning.

The beginning is when I was born, I guess, which is 1958. So I’ve been joking that I had my Jack Benny birthday this year: 39. I was raised Methodist; pretty nominal. It wasn’t very vital, and there wasn’t much fire there, for whatever reason. So it took really, till 1977 to become an evangelical Christian.

Uh huh. How did that happen?

Basically, my brother Gerry, getting “saved” around 1971, and the spectacle of his long-haired friends comin’ around, carrying Bibles; truth is stranger than fiction! And just observing them; it kinda got me wondering, “what’s going on here? These people are talking about Jesus . . . ” I thought you had to be a square [to be a good Christian]. It’s kind of funny to look back.

The things that were important to you then, yeah . . .

Yeah, as a 13-year-old. But a big influence on me was the movies about Jesus that would come on.

Really?

Like The Greatest Story Ever Told. One time we were watchin’ that (this would be mid-70s, I guess), and my brother Gerry said “well, Jesus is God.” And I didn’t even know that! That’s how ignorant I was. I didn’t even know the Trinity. I said, “no, he’s the son of God!” And he said “no, He’s God the Son.” So I started thinking about . . . it gave me a different perspective, watching the movie, even, that this person is God in the flesh.

Yeah, I bet; it certainly would. You know, it’s characteristic: a lot of kids who are raised in various religious traditions grow up completely ignorant of what those traditions formally teach. You were raised Methodist, which of course believes in the tri-unity of God and the deity of Christ, but by the time you hit your teens, anyway, you didn’t even know that . . .

At least in the Catholic tradition, generally kids are going to parochial school; they get some kind of catechetical instruction. But I really didn’t have that. I didn’t have a good Sunday school, or much at all. I think if I had learned earlier, some of the things I learned later, that I think I would have had more zeal for being a Christian.

Mm hmm. So when do you usually date your conversion to Christ, or your commitment to Jesus?

That would be 1977, and it took a huge depression that I went through. I was 18 years-old at the time, and God — the way I look at it — God more or less had to put me right on my back to see that I couldn’t survive on my own. Because I was under this illusion, “well, you don’t need God.” I had lived for ten years without goin’ to church — a very secular life; kind of like what you see in England now, where 4% go to church every Sunday.

Yeah, . . . yeah. Once having committed your life to Jesus, were you immediately on fire?

For a few days. Then I kinda went back into a lukewarmness for three more years.

Wow.

I would go to Bible studies, at Messiah Church [an evangelical Lutheran church with an outreach to the inner-city and young people]. That’s a very good church. It was a good place to start. But I didn’t even go to church on Sunday; I just went to the Bible studies. And I would read things like Hal Lindsey, which interested me because of prophecy.

Yes.

But in 1980, when I went to Shalom House (where Al used to be the pastor — if people don’t know that here); that’s when I really started to — I would say — commit myself to Jesus, and since then, it’s been pretty constant.

Yeah . . . and that was before I was pastoring there, to give all due credit to Joe Shannon, who was pastor at the time.

Yeah, Al got there six years later . . .

What was your experience like as an evangelical?

I loved it. I was thinking, driving out today: [in] most conversion stories I hear from Catholics, they don’t run down their evangelical experience.

Right.

They see it as kind of a stepping-stone. So I have great memories and fond memories. I learned all about the Bible when I was there, good moral teaching. I just think there was more to it that the Catholic Church can offer, along the lines of sacramentalism and tradition and matters of Church and authority.

Yeah. Now, when did it first dawn on you that you wanted something more than you were receiving in this particular evangelical setting?

I went about ten years being an evangelical, and involved in counter-cult ministry and my own campus ministry, and then in the late 80s, I started becoming involved in Rescues (Operation Rescue: pro-life activities). Even then, I didn’t have a sense that there was something more that I need, than I have now. So it really goes all the way up to 1990, when I started having a discussion group. I invited two Catholics that I had met in the Rescues, and that started getting me thinking, when they would start answering questions, because I used to think, “Catholics don’t have any answers to these questions . . . ” I had very little experience talking to informed Catholics, unfortunately. And then I met one, named John McAlpine, who’s a good friend of mine, that could actually answer things that I would ask him. And he just got me curious, and I started studying at that point, in 1990.

What were the questions that were most puzzling for you?

At that time, being a pro-life activist, I was curious about contraception, where Catholics would be against that – or supposed to be against it; the Church is against it — and they would make a connection between that and abortion. And I’d try to figure that out: “what connection does that have, because one is trying to prevent conception; the other is killing a child?” That got me thinking. And they’d tell me facts like, “the whole Christian Church was against contraception until 1930.”

Did that bother you?

Yeah, that gave me a start, because I always valued Church history. So, to hear that fact, it was kinda like a bombshell. So I thought, “man, if it was unanimous up till then” . . . I thought it was a stretch to believe that in our century, that we would get a moral teaching right, and 1900 years had messed it up . . . Of all centuries, with all the murder we’ve had in the 20th . . .

I was gonna say, the bloodiest century in the history of the human race . . .

Yes, exactly.

And all of a sudden we have some grand new moral insight.

The light goes on . . .

Yeah; that’s good . . .

It’s interesting, too, how in 1930, it was the Anglicans, in their conference that year, that changed it, and they talked about “hard cases,” just like we’ve heard in our time.

Sure.

So it’s the same kind of mentality: “it’s only in hard cases, and we won’t expand it any further than that.” But obviously it has been [expanded].

Yeah. We’ve got three instances that come to mind here: the contraception case, which was argued [on the basis of] hard cases, “so let’s permit it here”; then you have Roe v. Wade; “hard cases, well let’s permit it here”; and of course the case before us today has to do with assisted suicide: “well, we need it for hard cases.” But if the hard case argument has any historical meaning, then we know that what was once the hard case becomes the normal case.

That’s right.

So contraception has become well accepted under not just hard circumstances, but in almost all circumstances — same thing with abortion. And my guess is, you’ll have the same thing with assisted suicide. Hard cases make bad law . . . So at the 1930 Lambeth Conference, the Anglican Church goes ahead and permits contraception in tough cases; the first time any Christian Church has permitted the use of contraception. John McAlpine tells you that; you’re shocked; you say, “wait a minute! I don’t think we’ve got any grand new moral insights in the 20th century that the Christian Church has missed for the last 1900 years.” So that shook you up a bit. What’d you do? What’d you do about that?

Basically I didn’t have a defense for that. I just stood there, silent, at one of the meetings — I don’t know if it was during the meeting or after. But I just started thinking about that issue, and I became convinced, that . . . I tried to work through the distinction between contraception and Natural Family Planning, which is permitted for Catholics. And I came to realize that in one case you’re deliberately thwarting a possible conception; you’re going ahead and having sex anyway, and it’s kind of against the natural order. You don’t even have to appeal to Church authority to know the wrongness of it, if you reflect on the morality.

Then I remember one time, you were at my house, and made this analogy of — I was convinced by then, but it makes sense — comparing that to how when people eat, you have the nutritional aspect and the taste buds. That people would think it strange if you separated one from the other; if you just ate for pleasure or vice versa. And I thought that was good. I don’t know if that’s original with you, or where it came from.

I don’t know where it came from, either, but yeah, I do remember that. You weren’t yet a Catholic at the time, or were you?

No; at that time – the middle of 1990 — I was evangelical. And I remember thinking, “well, if I change my mind on this, I’ll be in a small minority among evangelicals . . . ” And I knew what the implications of that might be. It could develop further, but I still would have said, “well, it doesn’t mean I’m gonna be a Catholic.”

Right, right.

But I thought it strange that the Catholic Church had, I thought, the best moral theology of any church. So I thought, “how could they be right about these things, and be so wrong on Mary and the pope?,” and the typical things that evangelicals don’t like.

Yeah. So really, your entrance; your being wooed into the Catholic Tradition, was through this question of contraception? That’s the beginning?

The very first thing, yeah.

Where does it move from there?

Well, that brought to my mind matters of “What is the Church?,” because I believed that there was such a thing as the Church, with a big “C”. And I found it interesting. I was in counter-cult ministry, and they had this habit of talking about, “well, the early Church condemned Arianism in the Council of Nicaea.” They’d have this notion of the Church. But then somehow that gets lost after Luther comes on the scene; all of a sudden now, it seems like evangelicals are reluctant to talk about the Church, because they know it usually refers to us. We’re the only ones who use that terminology (well, the Orthodox, do, too). So I started thinking, “how does that work out?” I had a view that the early Church was Protestant. It became corrupt with the Inquisition and the Crusades.

And then — I mentioned in the book — Luther picked up the ball in the 1500s; it sort of switched over to Protestantism at that point. The Catholic Church was still Christian, but it wasn’t what I would call the mainstream. The evangelicals were really where it was at and the Catholics: they had enough truth, but not enough . . . they could still be saved, but they were just in a different league — that’s how I used to think.

Hmm; interesting. So, you began to question what it means to be “the Church” and how you can consistently use that phrase: “the Church,” because, of course, unless you have some sort of visible unity, then how do you know who’s in and who’s out? Who really speaks for the Church?

Yep.

When was that settled for you?

At that time — we’re still in the middle of 1990 — in my discussion group every two weeks, we were talkin’, and John and another friend of his named Leno (really good Catholics and committed pro-lifers) . . . it was just observing them: the faith that they had and the answers they would give . . . But I would try to shoot down the idea of infallibility. I would say, “Ok, you guys can be the Church, or a Church, but you’re not infallible.” I thought that was just totally out of the ballpark. That couldn’t be: there were too many errors, and there was the Inquisition, and so forth. So I started doing my own study, and even going to Sacred Heart Seminary and trying to shoot down the Catholic Church. I found the typical things that people bring up, about Pope Honorius, who supposedly was a heretic, but it was all from a kind of jaded viewpoint.

As I look back, I wasn’t being objective; it was like special pleading: you go in there with an idea and try to just find what fits in with it. And so, when I look back at that, I can see that it was sort of a dishonest effort; that there are good Catholic answers to all these so-called charges of heresy. And we see it; it comes around. This kind of stuff is being talked about today, even within the Church. Like Hans Kung and his book Infallible? An Inquiry. It’s the same kind of thing, but on my website I have a book that refutes that, by Fr. Joseph Costanzo. So there are answers to these things. Catholics just aren’t aware of them, by and large.

Yeah. And it’s part of the problem. How do you go about empowering the laity, so that they have this background in history and theology and Scripture. This is a major issue, it seems to me, facing the Catholic Church today.

Yeah.

We’ve got such grand impetus from Vatican II and from this present pope about the necessary role of the laity in carrying out the priorities of the kingdom of God and of the Church, and yet we find, at the same time, really very few Catholic bookstores; very few places where people can find information. I hope now with the Internet out there . . .

Thank God for that!

. . . people can have access . . . and get their education, and learn a little bit more about Church history and theology and Scripture.

You’re still not in the Church yet . . . what finally starts pushin’ you over the line?

[John Henry Cardinal] Newman. My friend John became totally exasperated with my constant questions. I was getting into some pretty technical things, and he hadn’t done the study, so, understandably, he wouldn’t be able to figure out Honorius, and all these things in history. So he said, “why don’t you read Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine?” — which is considered the classic on that subject. And of course, Newman is a genius; he lived in the 1800s.

So I started reading that book, and basically it destroyed the whole conception that I had, this notion that the early Church was simple and Protestant, and became corrupt . . . because he develops (no pun intended) the idea that you can have a development as opposed to a corruption. A doctrine can grow, but it doesn’t have to be a corruption, because it remains the same in essence. What’s happening is that you just understand more. You can find this in Augustine and early Fathers; it’s there — the idea is there, and I think it is the key to Catholic history; why we think we’re the apostolic Church, and Protestantism broke off of that, because their doctrines – many of them – didn’t develop; they just sprang into existence.

So that was for you a turning point in dealing with this idea of “why does the Catholic Church, with this luxuriant overgrowth of custom, and teaching, discipline, and liturgy; why doesn’t it look more like what Paul is describing in 1 Corinthians 12-14?” — which looks more like a primitive pentecostal church service.

Yeah; we had this notion that — probably you did, too — the early Church was this bunch of “Jesus Freaks” runnin’ around, meeting in caves. You know, they didn’t believe in the Eucharist, or any of that kinda hifalutin’ stuff. But that’s really not what you find. I didn’t do this at the time, but since then, I’ve read the Apostolic Fathers, and you see that it’s very “Catholic.” They believed in Real Presence, and regenerative baptism — all the things, pretty much, that Catholics believe today, only in more primitive form. You didn’t have — particularly — the idea of Scripture Alone / sola Scriptura. It’s just not there.

People will quote the Fathers, extolling the Bible, and they’ll say, “well, see, they’re Scripture Alone.” But no, they’re just saying the Bible’s a great book (of course, everybody agrees with that). Catholics think that . . . The bottom line is the question of authority: who has the authoritative interpretation of Scripture? No one’s denying that Scripture is God’s Word. And the Catholic Church has an impeccable record on that score. So it’s a question of authority, and the Church Fathers would appeal to apostolic Tradition, or succession. They would say, “we trace ourselves back to the Apostles; therefore we have true Christian teaching.” And that was the basis of it, rather than Bible Alone. Because people would disagree on that basis, as they do today.

Once that obstacle is removed for you: the idea of a developing doctrine, what remains?

At that point, I told myself, “okay, now I have the Catholic viewpoint of history, so I need to look at the Protestant ‘Reformation’ and determine, ‘what is the Protestant Reformation?’ ” I had read a little bit about it, but I wanted to get more in depth and maybe read the Catholic views of it — get the other side . . . Because, there again, you have this myth that Luther came . . . and somehow the Bible was in chains, and the Church was in darkness, and Luther comes out and brings the Bible to the people . . . And there’s a lot of mythology there, because, for instance, a hundred years before Luther’s time, there were fourteen versions in German of the Bible. By Catholics. And yet the popular notion is that no one had the Bible, and they were chained . . . and that’s because of the printing press. You didn’t have widespread literacy and Bibles until the printing press, and that was only in the 1450s. So, there’s a lot of that kind of . . . it’s really anti-Catholic at its core, the idea that the Catholic Church was somehow suppressing the Bible.

Yeah; putting a deliberately negative spin on these historical circumstances. And there were cases, of course, where you have legitimate debates over what is an acceptable interpretation, as the debates between Sir Thomas More and William Tyndale show, where the Church had to act, just as any government would act to protect people under its charge; the Church has to act to protect people from bad translations. In its lights at the time, they saw Tyndale’s translation as a bad translation.

Yes; that’s really the Catholic answer to this charge that “you suppress the Bible!” And we say, “we just suppress bad translations of the Bible.” That’s nothing more than fundamentalists do today. They say “this is a liberal translation.” It’s the same exact thing, but it has that slant to it because they assume that we’re somehow anti-Bible, which is absurd. We’re the ones who preserved it for a thousand years! You know, you hear about these monks and their manuscripts: these beautiful books. So people should just know more about the history; that’s really what needs to be done.

So then, where do you move, after that?

At that time I read a book called Evangelical is Not Enough, by Thomas Howard. He’s a great writer. I see him as the successor to C. S. Lewis, stylistically. And he showed how the liturgy was . . . the Catholic Mass had this transcendent quality to it, that transcends time and space. It’s a fantastic book. So that gave me a feel for liturgy, which I had virtually no experience with, or that much love for, really, because I was evangelical low church. And I read a book, also, called The Spirit of Catholicism, by Karl Adam.

Oh yeah — one of my favorite books.

And that was just wonderful. And then at that point, basically it was just a matter of getting over the cold feet and the jitters.

Did you have this period of time where you kind of intellectually were persuaded, but somehow the will just wouldn’t grasp; wouldn’t jump?

Yes. The common thing with most converts is, “I think I believe it, but now I have to . . .” Kind of like getting married: “I have to do this, and it just has to be done.”

What finally warmed your heart to move, then?

I was reading a little meditation by Newman, called Hope in God the Creator. And it ended with a whimper; whatever resistance was there . . . I said to myself, “well, no, I’m a Catholic now, I believe everything, so now’s the time.” So it just happened. And there’s a lot of other stuff, but that’s basically it.

Well, I remember when you were going through that. I had stopped pastoring at the time, and was also moving in the direction of the Catholic Church, and yeah, I had no real resistance to offer you. I thought you didn’t have too many options, Dave.

That’s bad when your former pastor has nothing to say . . .

Well, the story is well told in Surprised by Truth, . . . I wanna thank you so much, Dave, for being with me. And we’ll talk again.

It’s been great; been a pleasure.

Dave Armstrong: longtime friend and now Catholic apologist and free-lance writer. His story is told in Surprised by Truth.

*****