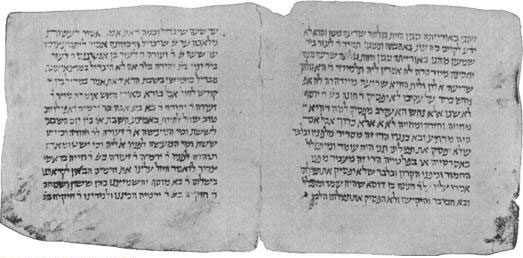

Reb Yhoshua gives his introduction to the topic:

The doctrine of the Oral Torah is one of the defining beliefs of traditional Judaism. Rabbi Moses Ben Maimon (Maimonides) included it among his Thirteen Principles of the Jewish Faith, [2] all of which a Jew must believe in order to be religiously identified with the people of Israel. Most Messianic Jews reject it as mere tradition, but for Orthodox Jews, it is the backbone of halakha, Jewish Law. It is the flesh on the liv-ing frame provided by the Pentateuch. In his introduction to Mishnah Torah Maimon-ides wrote, “All the precepts which Moses received on Sinai were given together with their interpretation.” [3] Contrary to the perception of many Messianic believers, the Oral Torah is not believed by Orthodox Jews to be the collective teachings of the Rabbinical Sages. Traditional Judaism holds that it was divinely revealed to Moses, and passed down to the sages by word of mouth until it was partially codified by Yhudah HaNasi, who gathered it into the Mishnah. [4] Further codification was resisted at first. The oral Torah was meant to be oral. But when it became clear that the transmission process was decaying even more, Rav Ashi gathered the tradition into the [Gemara]. [5] Together the [Gemara] and the Mishnah comprise the Talmud, the modern embodiment of the Oral Torah. The Talmud, however, is not simply a book filled with laws. It was written in very compact language that was designed to keep the Oral Torah largely oral.

[2] Maimonides, Commentary to Mishnah, (Sanhedrin ch. 10). Maimonide does not use ‘Oral Torah’ in his Ani Maamin. It is universally accepted that Principles eight and nine refer to both the Written and Oral Torahs.

[3] Isadore Twersky. A Maimonides Reader. (New York: Luhrman House, Inc. 1972), p35

[4] Ibid p36

[5] Ibid p37

First, he provides the example of the prophet Samuel sacrificing in the high places: [1]

According to the written Torah, sacrifices were not permitted anywhere but at the Tabernacle. (Lev 17:1-5) . . . After the Tabernacle was erected the written Torah does not seem to endorse the High Places at all. (Lev 17:8-9) One of the most startling proofs that an oral Torah existed is that the prophet Samuel con-tinued to sacrifice at the High Places after the Tabernacle had been built. When Saul first met Samuel, Samuel was preparing a sacrifice at one of the High Places. (1Sam 9:12-13) Later in Israel’s history, Israel would be strongly rebuked for sacrificing at such cult sites, but because the Tabernacle was not at Shiloh or Jerusalem, the text of 1 Samuel seems to defer to the oral Torah, and allows the apparent transgression to pass without comment.. . . The only explanations possible are that either a leni-ency existed that was not mentioned in the written text of the Pentateuch, but was ordained by G-d and known to Samuel; or that Samuel was spiritually severed from Israel on the same day that he met Saul. Because Samuel continued to serve G-d and Israel for many more years, it is doubtful that he had been spiritually cut off from his people.

God had made the following condemnation in the Torah: “. . . I will destroy your high places . . .” (Lev 26:30). And it had been written a few hundred years before Samuel’s time:

Joshua 22:29 Far be it from us that we should rebel against the LORD, and turn away this day from following the LORD by building an altar for burnt offering, cereal offering, or sacrifice, other than the altar of the LORD our God that stands before his tabernacle!”

Reb Yhoshua then shows how Sabbath regulations [2] went far beyond the written Torah:

Jeremiah 17:21-22 Thus says the LORD: Take heed for the sake of your lives, and do not bear a burden on the sabbath day or bring it in by the gates of Jerusalem. [22] And do not carry a burden out of your houses on the sabbath or do any work, but keep the sabbath day holy, as I commanded your fathers.

He comments:

In all the passages in the Pentateuch regarding the Sabbath, none of them ever forbids carrying objects out of one’s dwelling. . . . According to the book of Jeremiah, however, Jerusalem was destroyed for violating this oral tradition.

Jeremiah 17:27 But if you do not listen to me, to keep the sabbath day holy, and not to bear a burden and enter by the gates of Jerusalem on the sabbath day, then I will kindle a fire in its gates, and it shall devour the palaces of Jerusalem and shall not be quenched.

Surprisingly enough, the written Torah never specifies that Jerusalem [3] would be the central place of worship, or that a Temple [4] was to be built there (neither the words “temple” — in this sense — nor “Jerusalem” ever appears in the Pentateuch or Torah: first five books of the Bible).

The written Torah never acknowl-edges Jerusalem as the proper place for worship, and only briefly mentions that the L-rd will someday chose a special place for Himself. (Lev. 18:6) Only the oral Torah identifies the chosen place as Jerusalem, yet David knew where he wanted to build the Temple. The written Torah also gives detailed instructions for how to build G-d’s sanctuary. It was to be a tent erected by the priests. . . . there is no provision in the Torah for a permanent structure to replace the Tabernacle. It was forbidden to add or detract from the commands that G-d gave to Moses (Duet. 4:2), and Moses never wrote down any plan for the Tabernacle to be permanently folded up and put away. If G-d did not pass his plan to someday have a Temple on to Moses, than all of Israel’s worship from the reign of Solomon on was invalid. Be-cause Jesus frequented the Temple, Messianic Jews, as believers in Jesus as sinless, can be sure this too was clearly not the case.

Reb Yhoshua notes that Jesus was a follower of the Pharisaical tradition [5]:

It is easy to overly simplify Jesus’ relationship with Pharisaic Judaism by anachronistically projecting modern Protestant doctrine into the New Testament. . . . The fact that Jesus also had differences with the Sadducees, the virulent anti-Oral Torah sect, is often downplayed; as is the fact that whenever he disagreed with them, it was because he held to a doctrine found only in the oral Torah – resurrection from the dead.

I noted this in an old paper of mine:

Jesus Himself followed the Pharisaical tradition, as argued by Asher Finkel in his book The Pharisees and the Teacher of Nazareth (Cologne: E.J. Brill, 1964). He adopted the Pharisaical stand on controversial issues (Matthew 5:18-19, Luke 16:17), accepted the oral tradition of the academies, observed the proper mealtime procedures (Mark 6:56, Matthew 14:36) and the Sabbath, and priestly regulations (Matthew 8:4, Mark 1:44, Luke 5:4). This author argues that Jesus’ condemnations were directed towards the Pharisees of the school of Shammai, whereas Jesus was closer to the school of Hillel.

The Encyclopedia Judaica (Jerusalem: 1971) backs up this contention, in its entry “Jesus” (v. 10, 10):

In general, Jesus’ polemical sayings against the Pharisees were far meeker than the Essene attacks and not sharper than similar utterances in the talmudic sources. This source contends that Jesus’ beliefs and way of life were closer to the Pharisees than to the Essenes, though He was similar to them in many respects also (poverty, humility, purity of heart, simplicity, etc.).

St. Paul actually called himself a Pharisee twice, after his conversion to Christianity (Acts 23:6; 26:5). Jesus opposed the doctrine of the Sadducees (but not of the Pharisees: Matt 23:2). The Pharisees adhered to oral tradition and the Sadducees rejected it.

Reb Yhoshua observes that Jesus and the early Christians (even the Jerusalem Council) “held a standard of kashrut, proper eating [6], that was con-sistent with the Oral Torah” (his footnotes incorporated:

three of the four commandments that the Jerusalem Council insisted all believers observe immediately upon becoming Jesus believers dealt with food. (Acts 15:20, 29; 21:25) Two of these came from the oral Torah: not to eat things sacrificed to idols, [Mishnah Avodah Zorah 2:3] and not to eat things strangled. [Mishnah Chullin 1:2] The written Torah does not forbid either of these types of food, yet Jesus, in Revelation, is portrayed as strongly rebuking the communities of Perga-mum and Thyatira for breaking the ban on their consumption. (Rev 2:14 and 20) The authority of the Oral Torah in the lives of early Messianic believers cannot be doubted when half of the commands the Jerusalem council required of Gentiles were from the Oral Torah.

Jesus’ famous teaching on lust in the Sermon on the Mount [7] was derived from the oral Torah (footnote incorporated):

Many scholars have struggled with Jesus’ teaching, “You have heard that our fathers were told, ‘Do not commit adultery.’ And I tell you that a man who even looks at a woman with the purpose of lusting after her has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” (Mat 6:27) It seems to demand something impossible of men, something the written Torah never asked. . . . Jesus was not arbitrarily adding an unnatural stringency to the Torah; he was teaching from a tradition Moses received at Sinai, “Not only is he who sins with his body considered an adulterer, but he who sins with his eye is also considered one.” [Leviticus Rabba 23:12]

So were His teachings on prayer [8]:

Jesus’ ideas on prayer mirror those in the oral Torah, as well. He taught his disciples not to babble when they prayed (Mat. 5:7), and advised them to never stop praying for something they really needed. (Luke 18:1-6) What Jesus called babbling, Chazal labeled calculating, purposely making one’s prayers long so that they would be an-swered. Calculating, or babbling, was forbidden by the Oral Torah; [Babylonian Talmud, Berekhot 32b] and just as Jesus advised his disciples to continue asking G-d for what they wanted, the oral Torah commanded the Israelites, “If a man realizes that he has prayed and not been an-swered, he should pray again.” [Babylonian Talmud, Berekhot 32b]

A ninth example is Jesus’ reference to Talmudic tradition in discussing what appears to be a prohibition of masturbation (Matthew 5:30).

Conclusion: the oral Torah seems to be fairly conclusively established from the written biblical record. By analogy, Christian oral apostolic tradition is also upheld as valid in the new covenant, which was a direct development of the old covenant (Matthew 5:17-20).

***