My kind of guy!

*

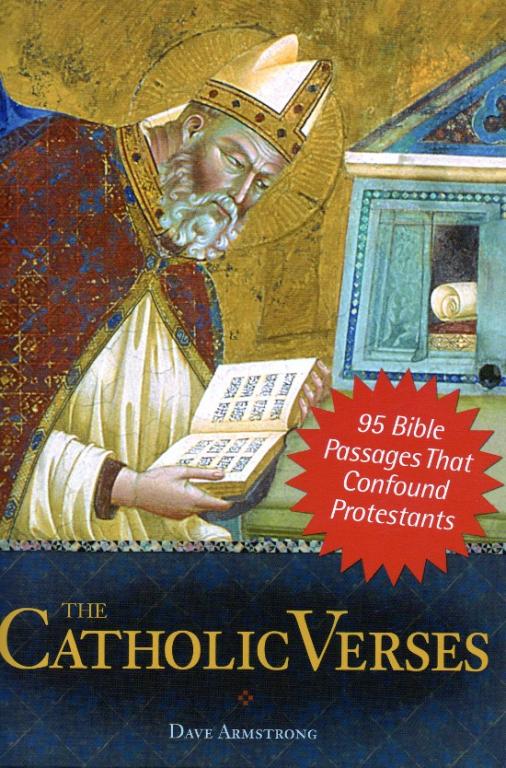

At the behest of others I decided to go ahead and read the whole thing. I ordered it online and received it just a few days ago. With pencil in hand and ready to take notes, I began to read to see if these “95 bible passages” really would “confound” me.

*

I take it that, thus far, they have not done so. But one never knows how much one may be influenced by reading different perspectives . . . I commend my critic for having the courage to interact with an opposing view by giving a fair read and then responding. And here I am counter-replying. It could turn out to be a constructive ongoing dialogue. I’m delighted about having an opportunity to defend my arguments in this book: one of my “officially” published ones (Sophia Institute Press).

*

The book is divided not by individual passages, but into sixteen chapters, each about particular subjects. Each chapter is then divided into sections, each with a few verses related to the topic. What I’ve decided to do is to respond to each individual section in individual posts. This will be a combination of a counterpoint and a continuous book report. As this is the introductory post, it’s only fitting that we review the…well…introduction of the book.

*

Sounds like fun. The Introduction can be read on the info-page for this book.

Strangely enough, the first thing I felt compelled to take notes on was the back cover, which begins with this:

*

Martin Luther ignited the Protestant Reformation by tacking ninety-five anti-Catholic theses to a church door in Germany. Now Dave Armstrong counters with ninety-five pro-Catholic passages from an authority far greater than Luther: the Bible itself.

*

Whether it was at the suggestion of Dave Armstrong or (more likely) the idea of Sophia Institute Press,

*

It was the latter, and I wouldn’t have used this phraseology in this particular context: partially for the reasons given by my critic. But Luther’s theses were ‘anti-Catholic” in the sense of generally “opposing current Catholic teachings and practices.” Not all of them were technically heterodox, as I understand.

*

Sometimes, yes. I find that both sides of the debate often have poorly thought-out definitions of the term.

*

Neither one is the definition that I and most scholars (historians, sociologists, etc.) utilize. It’s not referring merely to slanderers and nitwits like Chick (in the sense only of being a liar and misinformed fool or bigot); nor does it refer to mere theological opposition (that occurs internally among Protestants, and indeed among anyone who differs in a theological view with another Christian). The theological / doctrinal definition I use, and that scholars generally utilize, is:

*

One who believes that [“Roman”] Catholicism is not a species of Christianity and that one can only be saved by being a ‘bad [“Roman”] Catholic’ and dissenting from several [“Roman”] Catholic dogmas, and cannot be saved if all [“Roman”] Catholic doctrines are accepted in faith.

*

This is a belief that unites Chick, White, and Slick (I’ve countered White’s arguments dozens of times since 1995, and Slick’s a few times): look up their names on my Anti-Catholicism web page.

*

For another, even a casual review of Luther’s 95 Theses (source) shows them to be anything but “anti-Catholic.” We must remember that, at this point in Luther’s life, he was not criticizing the Roman Church as an institution or their doctrine in toto. Luther was not opposed to the doctrine of papal supremacy, purgatory, and other teachings (though he would be later on).

*

That’s correct. I agree. But he was soon after to massively dissent: to the tune of at least 50 departures by the year 1520: all before he was excommunicated. It’s only natural (though not minutely accurate) for Catholics to sort of project onto the 95 theses, Luther’s later heterodoxies (from our perspective). In historical matters, things usually get interpreted within the framework or matrix of later developments of the same things.

*

But for the purposes of this book, it was simply a nice catchy comparison: Luther’s 95 theses vs. the 95 “Catholic verses.” I believe the idea for that initially came from the publisher, as did the general structure of the book. I liked it and soon made it my “own” idea too.

*

The 95 Theses were posted to encourage debate on various matters concerning error that Luther perceived was happening within that institution. For example, he opposed the abuse of indulgences by Johann Tetzel, as seen in #27: “There is no divine authority for preaching that the soul flies out of the purgatory immediately the money clinks in the bottom of the chest.”

*

This is a just and correct criticism from Luther. It needs to be understood, however, that Luther was here attacking an abuse from Tetzel that was not itself Catholic teaching. To be fair to Luther, he may have understood this himself, since he wrote, “They preach mad, who say . . .” If he was saying that abuses occurred, but not necessarily that these were condoned by the Church, no Catholic who is familiar with the history in this regard would disagree with him. But many in our time do not understand this important distinction.

*

In his apologetics book, The Question Box (pp. 296-297 [New York: Paulist Press, 1929] ), Bertrand Conway treated this subject:

*

Catholic historians — Gasquet, Pastor, Janssen, Michaels, Paulus — have frequently mentioned the abuses connected with the preaching of Indulgences in the Middle Ages. The medieval pardoner . . . was often an unscrupulous rascal, whose dishonesty and fraud were condemned by the Bishops of the time. We find orders for their arrest in Germany at the Council of Mainz in 1261, and in England by order of the Bishop of Durham in 1340. To indict the Church for these abuses . . . is manifestly dishonest . . .

*

As both Pastor and Grisar point out, we must carefully distinguish between Tetzel’s teaching with regard to Indulgences for the living, and Indulgences applicable to the dead. With regard to Indulgences for the living, his teaching, as we know from his Vorlegung and his Frankfort Theses, was perfectly Catholic . . .

*“‘As regards Indulgences for the dead,’ Pastor writes, ‘there is no doubt that Tetzel did, according to what he considered his authoritative instructions, proclaim as Christian doctrine that nothing but an offering of money was required to gain the Indulgence for the dead, without there being any question of contrition or confession. He also taught, in accordance with an opinion then held, that an Indulgence could be applied to any given soul with unfailing effect . . . The Papal Bull of Indulgence gave no sanction whatever to this proposition. It was a vague scholastic opinion, rejected by the Sorbonne in 1482, and again in 1518, and certainly not a doctrine of the Church’ (History of the Popes, vol. 7, 349). Cardinal Cajetan at the time condemned Tetzel‘s opinion, and taught that ‘while we may presume in a general way that God is willing to accept Indulgences for the dead, we have no certainty whatever that He does so in any particular case. That is the secret of God alone.’ In 1477 Pope Sixtus IV had expressly taught that the Church applies Indulgences for the dead ‘by way of suffrage,’ for the souls in Purgatory are no longer subject to her jurisdiction. They receive Indulgences not directly, but indirectly, through the intercession of the living.”

The previous quotation was included in my first book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism, completed in May 1996 (on pp. 153-154), so I have been fully aware of it for at least fifteen years.

*

. . . I mean this series as no attack against Armstrong’s character or person, but rather his arguments and the contents of his book, both of which are aimed at Protestants.

*

Good; thanks. And I have the same attitude on my end.

*

From past experience I have too often been accused of acting as if I believe my opponents know nothing (being told “So-and-so is a lot smarter than you think they are,” etc.). We must recognize that having a disagreement with a person does not denote you think they are certifiably stupid.

*

Exactly right.

*

Amen!

*

This is equating two things that are not equivalent. My point was that Catholics and Protestants both revere the Bible as the inerrant, inspired, revelation of God. No difference there. How to interpret its authority and relation to Church and tradition is a separate issue, not equivalent to the Bible itself and how it is regarded, which is what I was referring to as “common ground.”

*

Although some lay Catholics claim that Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and other groups are the result of sola scriptura, the fact is that, in regards to the authority of scripture, these groups are closer to Rome than they are to historic Protestantism. All these groups, like the Roman Catholic Church, believe that scripture is sufficient only so long as it is rightly interpreted by their established governing body. Hence it is not really scripture that truly has the final say, but that “final authority” which gets the final say. However this “final authority” may interpret the Bible, we are to accept it.

*

This involves a long, detailed discussion about sola Scriptura, the rule of faith, the nature of tradition and of Church authority, and of material sufficiency of Scripture. I have written three books on these topics, and more papers on my site than on any other topic (see my Bible and Tradition page). Calvinists are no different from anyone else. They believe that they have a unique insight as to correct interpretation of Scripture. Hence, Calvinists believe in TULIP. If a Calvinists dissents from that belief-system, he is not considered an orthodox Calvinist. It’s assumed that this is the correct teaching of Scripture. But most Christians disagree with that. I devote over 100 pages of biblical refutation of TULIP in my book, Biblical Catholic Salvation. Whether the Bible teaches these doctrines in the first place is the issue.

*

That is the historic usage and current-day usage. Just look, for example, at the current debate over the contraception mandate of government. When people involved in that say “Catholic Church”, does anyone think people don’t know to what communion they refer? Many Protestants like to play games with the word Catholic. It gets quite ridiculous at times.

*

However, the Roman Church does not have a historical monopoly on the word. For example, the Eastern Orthodox Churches to this day still recite the Nicene Creed, wherein they confess and believe that they are the “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church” (source).

*

There is a wider use of the word catholic (lower-case). But that is also true of Reformed. Reform is a larger concept (hence we Catholics speak of The Catholic Reformation). But it can also be a title, just as Catholic can be a title. Hence, we refer to Reformed Judaism. That is a title. It doesn’t have the same meaning as Reformed Protestant (Calvinist). Yet a Reformed Jew might simply call himself “Reformed” and it is understood in context what that means. Likewise, “Catholic” as a title has a certain referent and anyone (pretty much) knows what it is referring to, because that is the use of the word as a widespread title.

*

Even Protestants have historically used the word “catholic”: the 1615 Irish Articles of Religion confess that “there is but one Catholic Church,” clarifying later that catholic means universal (source); the 1618 Belgic Confession states belief in the “one single catholic or universal church” (source); the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith speaks of the “catholic or universal church” (source), as does the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith (source).

*

But this is irrelevant in relation to what I just wrote, because we are using “Catholic” as our chosen title; secondly, Protestant use of the word redefines it in relation to its historical usage, so there is “sleight-of-hand” there that must be noted. The first thing any revolution does is redefine terms.

We must therefore be very careful when Armstrong describes the Bible as a “Catholic book, produced and preserved by Catholics for nearly 1,500 years before Protestantism even appeared” (pg. xvii), as if the other “apostolic” churches – such as the Eastern Orthodox, Coptics, and Church of the East – had nothing to do with the preservation of scripture.

*

They did (though the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome was central in the process). I wasn’t necessarily denying that. I was responding in this section to the insinuations that Catholics are supposedly hostile to Scripture. Again, my critic can’t see the forest for the trees. In his rush to criticize minute particulars, he misses the context and broad nature and rhetorical thrust of my point.

*

To provide an analogy that he and many Protestants could relate to, suppose I said that “Protestants don’t care about works at all.” This is untrue. It’s a misunderstanding of Protestant soteriology, just as the Catholic Church’s opinion of the Bible is widely misunderstood. Thus, in order to rhetorically counter the charge, one might say something like, “Good works are a Protestant idea. Protestants have taught the value and necessity of good works from the beginning. Both Luther and Calvin did so, and have for almost 500 years.”

*

Stating this is not meaning it in an exclusive sense. It’s making the point that good works is also a Protestant notion. It’s including Protestants in the “circle” of the theological notion of “the necessity of good works” whereas some try to exclude them and accuse them of antinomianism. Likewise, by analogy, I was making the argument that not only are we not hostile to the Bible, but to the contrary, we preserved it for 1500 years before Protestantism was ever heard of by anyone. Therefore, it is ludicrous and absurd for anyone to think that we denigrate or despise the Bible and its authority.

*

It is no surprise that men like Augustine or John Chrysostom used words such as “catholic” or “orthodox” – however, we cannot read backwards and use those words out of their historical context.

*

. . . which is exactly what Protestants often do: they reinterpret and redefine “Catholic Church” so they can literally be part of it, when, historically, the title meant a certain thing, and men knew exactly what that was.This is precisely why many Protestants habitually use the title “Roman catholic Church”: because they are following historic Anglican usage: invented to maintain the pretense that Anglicanism was still formally part of the Catholic Church: having rejected papal authority. The game had to be played of separation of the title from the one Church that it historically had always referred to. But the Roman rite is only one of 22 in the Catholic Church. To always say “Roman Catholic” is to ignore 21 other rites beside the Latin (Roman) rite in the Catholic Church. It’s not only historically and etymologically, but also sociologically misinformed.

*

In the same vein, we must note that when Armstrong writes of “Church and Tradition,” it is always within a strictly Roman Catholic context. While there are similarities between the various “apostolic” churches, there are also differences which cannot be ignored. For one, the Eastern Orthodox deny many Roman Catholic “apostolic” traditions, such as purgatory or papal infallibility. For another, they deny original sin and uphold a different view of justification along with a rather semi-Pelagian view of salvation.

*

Let them defend their own views. I am defending mine, so I assume certain things as premises, just as anyone does. My critic has his own premises, that I would dispute (and I am presently doing so). But it’s not circular reasoning. There is a consistent body of teaching: what we call apostolic tradition, that consistently develops from the original apostolic deposit: given by our Lord Jesus Christ to His Church: initially led by His disciple, St. Peter. This body of teaching is historically continuous and demonstrable as such by independent historiographical methods.

*

I have collected some of the historical data myself in my book, Catholic Church Fathers. I’ve had many debates with Protestants (evangelicals, Lutherans, Calvinists, Anglicans) about sola Scriptura and other Protestant distinctives, and I argued (again, with objective historical data: citations of the fathers) that novel Protestant beliefs brought in in the 16th century could not be historically traced back through the Church fathers to the apostles. See my Church Fathers web page for these debates.

It has nothing to do with my goal in the book. I am defending Catholic viewpoints and showing in this book how Protestant arguments fall short of the mark over and over. The book is primarily devoted to the failure of Protestant contra-Catholic arguments, whereas my first book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism, was devoted to a straightforward presentation of our arguments in favor of Catholic theology.

*

Once again, the critic, in his zeal, fails to comprehend the larger context of the purpose of the book. If he thinks I am unaware of Orthodox arguments, he obviously hasn’t perused my blog very closely. If he had, he would have discovered that I not only have published a book about Orthodoxy (that is being distributed to Czech bishops and will soon be incorporated into the Logos Bible Software program), but that I also have a web page devoted to Orthodoxy. It’s not the purview of this book. One can’t write about everything all at once. These are essentially silly misguided trifles and rabbit trails.

This might sound a bit harsh,

*

Whether it is or not, it is essentially a silly misguided trifle and rabbit trail.

*

I did that in my first book, and do it indirectly in this one (the two complement each other, since they have different aims), but the main purpose is to examine Protestant polemics against the Catholic Church. Therefore, by definition and intentional goal, Orthodox views are beyond the subject matter. I deal with Orthodox arguments in my book devoted to those.

*

Later on, we will see that Armstrong’s constant reference to “Church and Tradition” displays his more apologist than scholarly side, as hinted at earlier.

*

It’s a generic term in many instances, meaning, roughly, “authority matters, humanly speaking; beyond the Bible only.” The critic wants to blast my general use in a vague fashion. I am saying that he has a misunderstanding in the first place, and that in order for his objection to have force, he has to provide individual examples of the “shortcoming” he infers.

*

Oftentimes in my dialogue with members of “apostolic” churches, I’ve found that “Church and Tradition” is a fallback to authority without demonstration of how this authority is relevant to the topic of conversation.

*

More general twaddle, having little to do with the objective content of my book . . .

*

Nothing new here. Nicaea was an ecumenical council, and got it right. Jerusalem and Tyre and Constantinople were local eastern councils (and those were often rife with heresy). What the critic doesn’t grasp is that Rome was never corrupted by Arianism. I gave the following summary of Arianism vis-a-vis Rome in a 1997 paper:

*

Arianism held that Jesus was created by the Father. In trinitarian Christianity, Christ and the Holy Spirit are both equal to, uncreated, and co-eternal with God the Father. Arius (c.256-336), the heresiarch, was based in Alexandria and died in Constantinople. In a Council at Antioch in 341, the majority of 97 Eastern bishops subscribed to a form of semi-Arianism, whereas in a Council at Rome in the same year, under Pope Julius I, the trinitarian St. Athanasius was vindicated by over 50 Italian bishops. The western-dominated Council of Sardica (Sofia) in 343 again upheld Athanasius’ orthodoxy, whereas the eastern Council of Sirmium in 351 espoused Arianism, which in turn was rejected by the western Councils of Arles (353) and Milan (355).

*

. . . why does the Council of Trent anathematize anyone who says “by faith alone the impious is justified” (Canon IX; source)?

*

It is condemning a radical antinomian notion of faith alone that was and is not believed by mainstream Protestants. What Trent was condemning is condemned also by Luther and Calvin in many ways and many times.

*

Because no one can know for sure that they have such perseverance, per St. Paul’s statements:

*

1 Corinthians 9:27 but I pommel my body and subdue it, lest after preaching to others I myself should be disqualified.1 Corinthians 10:12 Therefore let any one who thinks that he stands take heed lest he fall.Galatians 5:1, 4 . . . stand fast therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery . . . You are severed from Christ, you who would be justified by the law; you have fallen away from grace.

Philippians 3:11-14 that if possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead. Not that I have already obtained this or am already perfect; but I press on to make it my own, because Christ Jesus has made me his own. Brethren, I do not consider that I have made it my own . . . I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.

1 Timothy 4:1 Now the Spirit expressly says that in later times some will depart from the faith by giving heed to deceitful spirits and doctrines of demons.

*

This follows upon the previous one you brought up. If it is possible for a person to fall from grace (as it is), then those can be justified who may later fall away, and hence were obviously not all predestined to salvation.

*

Because that is also a true, biblical doctrine.

*

Not necessarily at all.

*

Many Catholics – especially Catholic converts from Protestantism – love to try to portray a friendly mode of disagreement, but they cannot get around their church’s actual position towards non-Catholics.

*

It’s all perfectly consistent. Our view has developed through the centuries, and both sides understand the other far better than they did 500 years ago. Current Catholic ecumenism is exemplified in Vatican II, papal encyclicals (especially since Pope John XXIII), the Evangelicals and Catholics Together negotiations, and the Lutheran-Catholic agreements on justification and other areas, as well as high-level Catholic-Orthodox discussion. My critic can stay back in the 16th century if he likes. We are moving ahead and pursuing several lines of ecumenical talks.

*

*

They are brothers in Christ based on their baptism, and (more broadly) due to general agreement on things like the Nicene Creed, trinitarianism, grace alone, the divinity of Christ, His resurrection, and many common beliefs. But baptism is primary, because that incorporates one into the Body of Christ. We accept the validity of Protestant trinitarian baptism, and even Calvin accepted the legitimacy of Catholic baptism. “Heresy” has to be judged on the basis of individual errors, but it doesn’t follow that a person must not be a Christian at all. If they were baptized in a trinitarian fashion, they are Christians.

*

But if my critic thinks I am not a brother in Christ and not a Christian, then this discussion is over, because I don’t waste my time anymore debating with anti-Catholics. As far as I know so far, my critic is not an anti-Catholic (as I defined it above: standard usage). So I have answered. If it turns out that he is an anti-Catholic, however, the discussion will abruptly cease, per my time-management policy, now nearly five years old. This paper will remain, if so, because I spent several hours on it.

*

Sure (if the previous paragraph does not apply to him; if he can grant that Catholics are Christians and brothers in Christ, too).

*

I thank my critic for this opportunity for me to clarify our beliefs.