***

(9-30-07)

***

John Loftus is a former pastor and the webmaster of the Debunking Christianity blog. This reply is at his request. I give him points for originality, if little else. John’s words will be in blue.

John provided a general post that linked to other individual ones (I won’t give all the URL’s; the previous link gives those). In later ones, he merely repeats many of his arguments, so I need not cite everything. I will be meeting the basic arguments head on.

Here’s the short version of my argument. It begins with these four propositions:

1) Religious diversity around the globe is a fact—many religions can be found in distinct geographical locations in the world.

Sure.

2) There are no mutually agreed upon tests to determine which religion is true.

To some extent this is correct; however, at least for the western religions, there are several tests from various fields of study (natural science, archaeology, textual analysis, historiography, philosophical arguments, etc.) that can be brought to bear. Those from these traditions (Christianity, Judaism, Islam) hold lots of tenets along those lines in common, and so can compare the relative strength of their religious claims.

Eastern religion is another story, and the presuppositions and conception of God is so different that it is difficult to test or examine rationally by these same standards.

3) Religious apologists all claim they are correct and they reject all other distinctive religious beliefs but their own.

We all believe what we believe (religious or no) and believing one thing precludes believing simultaneously in another that contradicts it. Most religious people will readily admit, however, that many beliefs in other religions are similar or identical to their own. All religions and indeed ethical systems (whether religious or not) have great commonalities. This was a central thesis of C.S. Lewis’s book The Abolition of Man.

4) All religions seek to answer life’s most important questions in a believing communal social environment where the adherent is encouraged to believe and discouraged to doubt.

Sure. This is done in varying degrees of plausibility and rationality, but as a generality it is true.

These four facts form the basis of the argument. Okay so far? I think these facts are undeniable.

#2 is questionable to a significant extent, as argued. #3 must be seriously qualified.

So if you want a deductive argument expressing this inductive argument of mine, here it is:

p -> q:

If 1-4 is true, then it’s probable that people adopt their religion based upon “when and where they were born.”

They often (even more often than not) do do that; no argument there.

p:

1-4.

.: q:

Therefore, it’s probable that people adopt their religion based upon “when and where they were born.”

Based upon 1-4, it’s highly probable religious adherents will not investigate their faith dispassionately.

That’s exactly right. That is a major reason why I do apologetics. Religion needs to be held with a great deal more rationality and self-conscious analysis for the epistemological basis and various types of evidences for one’s own belief.

They will use reason to solidify and support religious beliefs arrived at prior to rationally examining them. And because there isn’t a mutually agreed upon scientific test to determine the truth of any religion, therefore social/political and geographical factors heavily influence what religion one adopts.

Again, this is undeniably true (except for the “testing” part). Of course it proves nothing whatsoever about the strength of relative truth claims, so I don’t see that it has much value except as a rather self-evident bit of sociological observation.

This conclusion is the strongest in those communally shared religions where doubt places the adherent in danger of hell, as well as the fear of losing the friendship of the religious community he or she is involved in.

Or places folks in danger of their lives if they dare dissent (or at least losing many freedoms, and their personal reputation), as in many Muslim countries, or Communist nations.

This conclusion leads to the presumption of skepticism when investigating any religious faith, including one’s own religious faith; for it’s probable that the adherents merely adopted their faith based upon “when and where they were born.”

I believe everyone should study to know why they believe what they believe. On the other hand, I deny that there is no religious knowledge or evidence other than these hard proofs from scientific inquiry. There are also highly complex internal or instinctive or subjective or experiential factors that have been analyzed at great length by philosophers like William Alston (see Alvin Plantinga (“properly basic belief”). Those are huge discussions, but not to be dismissed as irrelevant to the present line of inquiry.

John Loftus, in a second post, presents a typically presuppositionalist, Van Til-like excerpt from Paul Manata (who frequents Steve Hays’ Triablogue site). But before looking at how he disagrees with it, it should be known that most non-Calvinist Christians also disagree with this outlook concerning the relationship of faith and reason, and unbelievers and believers. In other ways, there is common ground with what is called “evidentialist” apologetics (my preferred brand). Alvin Plantinga shows one way of achieving a semi-synthesis.

I’ve written papers specifically denying (based on the biblical data) that atheists must be evil and immoral, and affirming that any individual atheist can possibly be saved in the end. I’ve also strongly denied the notion that any atheist who says he was a former Christian must be lying, since it is considered impossible. That is biblical hogwash.

Does this description of the thinking of an unbeliever confirm or deny what I have been saying, that Christianity must devaluate philosophy in favor of believing in historical knowledge of a “special revelation” in the Bible?

It confirms it but only in a very limited way, since this presents the viewpoint of only a small minority of Christians: strict Calvinists (mostly fundamentalists). Not even all Calvinists would take this strict of a view. Loftus makes a mistake very common in the atheist / agnostic / skeptical literature: confusing just one small sector of Christianity with the whole. It’s essentially a straw man because it is even less than a “half-truth” if we go by numbers of (thinking, informed) Christians proportion-wise who think like this.

And if a Christian must place reason below his faith, then how can he properly evaluate his faith in the first place, since the presumption of faith we start out with, will most likely be the presumption of faith we end with?

A Christian doesn’t have to. The Bible doesn’t teach this in the first place. The largest and most continuous Christian tradition (Catholicism) would flatly deny it. So do the majority of Protestants and Protestant apologists.

Since the presumption of faith we start out with is something we accept by, what John Hick calls, the “accidents of history” (i.e., where and when we are born), how likely is it that the Christian will ever truly evaluate his or her faith?

Many (and probably most) Christians never do that; I agree. Again, there is a reason why I have devoted myself to apologetics. If even an atheist thinks Christians should reason more about their faith, then it is obvious that the work of apologetics is crucial.

I would say, though, that there is a version of this “become whatever your surroundings dictate” argument that can be turned around as a critique of atheism. Many atheists — though usually not born in that worldview — nevertheless have decided to immerse themselves in atheist / skeptical literature and surround themselves with others of like mind. And so they become confirmed in their beliefs. We are what we eat. In other words, one can voluntarily decide to shut off other modes and ways of thinking in order to “convince” themselves of a particular viewpoint. That is almost the same mentality as adopting a religion simply because “everyone else” in a culture does so, or because of an accident of birth. People can create an “accident of one-way reading” too.

My position, in contrast, is for people to read the best advocates of any given debate and see them interact with each other. That’s why I do so many dialogues. John Loftus could write these papers, and they may seem to be wonderfully plausible, until someone like me comes around to point out the fallacies in them and to challenge some of the alleged facts. Read both sides. Exercise your critical faculties. Don’t just read only Christians or only atheists. Look for debates where both sides know their stuff and have the confidence to defend themselves and the courage and honesty to change their opinions if they have been shown that truth and fact demand it.

How is it possible to rationally evaluate the Christian faith when the Christian can only do so from within the presuppositions of that faith in the first place–presuppositions which he or she basically accepted by the “accidents of history.”

This is basically what the presuppositionalists do, but that is rejected by the majority of Christian thinkers today and throughout history. John’s critique applies only to them and to fideists and pietists who deliberately underemphasize or reject reason. it certainly does not apply to all of Christianity. The irony is that he makes a critique of something where I as a Christian and an apologist can largely agree with him. We disagree mainly on whether the critique affects Christianity as a whole or only one small — mistaken — school within it.

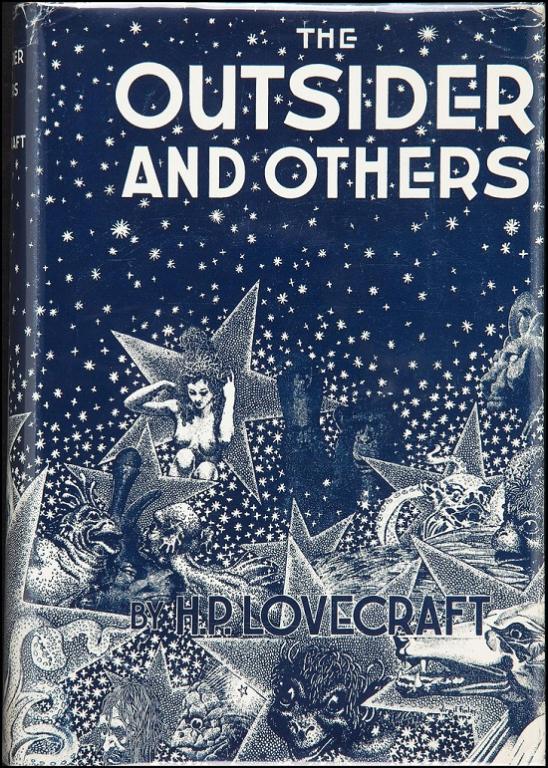

So let me propose something I call The Outsider Test: If you were born in Saudi Arabia, you would be a Muslim right now, say it isn’t so? That is a cold hard fact. Dare you deny it? Since this is so, or at least 99% so, then the proper method to evaluate your religious beliefs is with a healthy measure of skepticism.

Yes, it’s true. Most people believe in religious matters what they were born into. But of course, many change their minds later on. And we must also take into account variations within religions. In my case, for example, one could say “sure, you’re a Christian because most Americans claim to be so.” True enough on one level, but it is false insofar as it would presuppose that I am a Christian only because of this factor and no others.

In fact, I have made up my mind as an individual and often changed my opinions. I was born into a liberal Methodist family. I never resonated with that much, and stopped going to the Methodist church when I was ten. I then became a “secularist” or “practical atheist” for about eight years. That went against my background because both parents and all four grandparents were Methodists. I then converted to evangelical Christianity at age 18. There wasn’t much of that in my larger family, either. And at length I converted to Catholicism at age 32. There were virtually no Catholics in my extended family. So I was making decisions on my own regardless of what folks around me believed (particularly in my Catholic conversion). Therefore, this whole analysis doesn’t really apply to me, if we examine it closely and take it a step deeper and out of the broadest generalities.

Test your beliefs as if you were an outsider to the faith you are evaluating. If your faith stands up under muster, then you can have your faith.

That is essentially what I am doing in my numerous posted debates (more than 450 as of this writing; perhaps nearly 500 by now. I stopped counting). I interact with people who don’t agree with me, all the time., And so I am exposed to their premises and worldviews and in a good place to judge if it is superior to my own. Obviously I haven’t been dissuaded of Catholic Christianity yet. And I can demonstrate to anyone why, by directing them to my debates with atheists and Protestants (i.e., anyone non-Catholic).

If not, abandon it, for any God who requires you to believe correctly when we have this extremely strong tendency to believe what we were born into, surely should make the correct faith pass the outsider test. If your faith cannot do this, then the God of your faith is not worthy of being worshipped.

I agree that every Christian should have a reasonable faith, that can withstand rational and skeptical examination. I do this myself and I write so that others can share in the same confidence and blessing that I receive as I do apologetics and interact with other people of different beliefs.

What we believe does not depend entirely on where we are born. It also depends on when we were born, and what beliefs and conditions were there when we grew up. What would you believe if you were born during the Middle Ages, or during the Ancient superstitious days before the rise of modern science, Frontier days in America, pre-civil war days in the South, and even pre-depression era days, WWII days, Vietnam protest days, the greed decade of the 80’s, and the microchip and cell phone revolution now? Is human reason that malleable? I think so.

None of this means there isn’t any truth, moral or otherwise. But this is known as the Dependency Thesis, whereby what we believe depends upon these factors world-wide. Yep, that’s right, world-wide. And while it doesn’t prove anything about truth itself, it should give us all pause to consider the factors of where and when we were born, and whether or not we properly are evaluating our faith.

All true, again. And I agree that “it doesn’t prove anything about truth itself”. I have long accepted the sociological basis of much actual belief, on account of my reading of social analysts such as Thomas Kuhn (The Structure of Scientific Revolutions) and Michael Polanyi. See also psychiatrist Paul Vitz’s analysis of the familial background of many famous atheist figures. This also is a result of my degree in sociology and minor in psychology.

There are so very many things we believe because of when and where we were born that an argument is made by moral relativists based on it, which is known to ethicists as the “Dependency Thesis (DT)” According to the DT our morals are causally dependent on our cultural context. Even if the relativists are wrong in the very end, they make an extremely powerful case which should give the over-confident Christian a reason for a very long pause, if nothing else.

I don’t see why. Every person is responsible for his own intellectual advancement. The trouble is that public education is so rotten today that young minds aren’t formulated in ways that would further this end. They are spoon-fed secularist propaganda bleached of any Christian influence whatsoever, and then given a massive sophisticated dose of anti-Christianity in college (so that many students lose their faith because they are so overwhelmed and unprepared), as if this were a fair, intelligent way of going about things. They are what they eat too.

That’s why secularists are so intent on removing any vestige of Christianity from education, because they prevail only by people being ignorant of alternatives and being presented one side only. I was a thoroughly secularist pro-choice, pro-feminist, political and sexual liberal coming out of high school. I would have repeated the party line impeccably (in marvelously blissful ignorance). But when I started reading some materials with a different perspective during my college years and shortly afterwards (Christian, politically conservative, pro-life), then my opinions changed because I had a rational basis to compare one view with another, rather than ape propagandistic slogans learned by rote repetition (which is much of liberal, secularist education these days).

The Christian believes God is a rational God and that we should love God with all of their minds. The Christian is not afraid to examine his or her beliefs by the test of reason because he or she believes in a God of reason. A small minority of Christians even believe Logic and reason presuppose the Christian God.

So what’s the problem here? Why aren’t Christians posting by the droves and saying, “Fine, I have no problem with The Outsider Test?” Why not?

Because they are insufficiently acquainted with historic Christianity, biblical Christianity, and historic apologetics. They are fair game to eventually lose their faith, or else possess such a weak, mangled, ineffective faith that they make no practical difference to anyone around them, as potential “witnesses” of the truth of Christianity.

An outsider would be someone who was only interested in which religious or nonreligious view is correct, and assumed from the start that none of them were true–none of them!

But there are no absolutely clean slates. This is where I would disagree, based on the analyses of people like Plantinga, Alston, and Polanyi (the latter almost singlehandedly dismantled logical positivism).

An outsider is a mere seeker who has no prior presuppositions about any faith, or no faith at all. To be an outsider would also mean we would have nothing at stake in the outcome of our investigations, and hence no fear of hell while investigating it all. These threats could hinder a clear-headed investigation.

I deny the premise, and so am skeptical of this scenario; however, I do believe in being as objective and fair as we possibly can be, even given our inevitable biases and belief-system that cannot be erased merely by playing the game of philosophy and supposed extreme, dispassionate detachment.

What exactly is wrong with this? While I know it may be impossible to do, since we all have presuppositions, what’s wrong with striving for this as a goal that can only be approximated?

I agree, if qualified like this. Good.

If Christianity wins hands down in the marketplace of ideas, like so many seem to indicate, then why not mentally adopt this test? Christians shouldn’t have any problems doing this, right?

Amen! I try to do it by my debates, such as the present one. I think Christianity wins in any such encounter. It’s always been my experience.

The outsider test would mean that there would be no more quoting the Bible to defend how Jesus’ death on the cross saves us from sins. The Christian must now try to rationally explain it. No more quoting the Bible to defend how it’s possible for Jesus to be 100% God and 100% man with nothing left over, by merely quoting from the Bible. The Christian must now try to make sense of this claim, coming as it does from an ancient superstitious people who didn’t have trouble believing this could happen (Acts 14:11, 28:6), etc, etc. Why? Because you cannot start out by first believing the Bible, nor can you trust the people closest to you who are Christians to know the truth. You would want evidence and reasons for these things. And you’d initially be skeptical of believing in any of the miracles in the Bible just as you would be skeptical of any claims of the miraculous in today’s world.

This is a description of apologetics, pure and simple. Thanks for confirming the value of what I have devoted my life to.

. . . we would do well to question the social conditions of how we came to adopt a particular religious belief in the first place, that is, who or what influenced us, and what were the actual reasons for adopting that belief in its earliest stages.

I agree wholeheartedly.

If you’ve read my Conversion/deconversion story, I had no initial reasons for adopting the Christian faith, except that everyone I had ever met believed. The reason I adopted it in the first place was because of social conditions–no one I knew doubted it and I concluded at the age of 18 that therefore it must be true.

My story was precisely the opposite. I was so utterly ignorant of Christian theology at age 18 that I didn’t even know that Christians believed Jesus was God in the flesh. I arrived at all my Christian beliefs by my own deliberate study. I had gotten secularism crammed down my throat in Detroit public schools and Wayne State University in Detroit. I had to “even the score” a bit by my own study of the theistic intellectual tradition. That was a bit tough to do in a fair way, given, for example, that there wasn’t a single theist in the philosophy department at Wayne when I was there and took five courses or so.

. . . . there are no empirical tests to finally decide between religious viewpoints.

This is simply not true. There are a number of evidential or empirical tests that Christianity and other religions can be subjected to. The argument from biblical prophecy offers a chance to test by real, concrete historical events whether the predictions were accurate or not. A study of Jesus’ Resurrection, that involved a dead body and a rock tomb guarded by Roman soldiers, provides hard facts that have to be dealt with and explained somehow. The cosmological and teleological theistic arguments offer hard scientific facts and details that are rationally explained as suggesting a God. All miraculous claims can be examined.

In the Catholic tradition, there are many eyewitness accounts of people being raised from the dead (St. Augustine, for example, attested to this). There are all sorts of miracles. For example: the incorrupt bodies of saints. If you can take a dead person out of their grave twenty, fifty years or more after their death, and the body has not decayed, and it is because they were a saintly person, then that is hard empirical evidence that confirms Christian, Catholic teaching. You have the mystery of the stigmata, that could be seen in, e.g., St. Padre Pio, who died in 1968. There is archaeological evidence confirming the claims of the Bible. Etc., etc.

Skeptics thumb their nose at all of this but it is not nearly so simple. There are unexplained phenomena here that have to be accounted for. We have our interpretation, but the atheist puts his head in the sand and claims that it’s all impossible because of their prior axiomatic beliefs that all miracles are impossible because they “go against science ” (itself a blatant fallacy). Hence John writes: “Christians believe God did miracles in the ancient past (but we see no evidence he does so today, which is our only sure test for whether or not they happened in the past).” And that is considered “open-minded” and intelligent.

A believer in one specific religion has already rejected all other religions, so when he rejects the one he was brought up with he becomes an agnostic or atheist many times, like me.

We need not reject all other religions in toto; just aspects of them that we believe to be untrue. For example, Confucius taught excellent personal ethics. A Christian would disagree with very little there. We have no objection to Jews following the 613 commandments of Mosaic Law or keeping kosher. Buddhists are often pro-life, and teach about personal asceticism something not unlike Catholic monasticism. Muslims still have kids, are against abortion and premarital sex and pornography. All great stuff.

You quoted Paul, for instance. Why should I believe what an ancient superstitious person believed and said?

Here is the classic atheist condescension and double standard. We’re supposed to sit like eager baby birds receiving regurgitated worms from their mother’s beak, in hearing atheists lecture us about the Bible and how stupid and contradictory it is, and how dumb our interpretations are. John cited the Bible and beliefs stated in the Bible all over his main post. But the Christian is not allowed to cite the Bible in his replies (???!!!).

Thus John waxes indignantly: “Deal with the argument. The Bible means nothing to me.” Well, how the hell is a Christian gonna be able to respond to an argument of biblical skepticism and alleged contradictions by not citing the very Bible that was critiqued? It’s irrelevant whether John accepts it or not or puts it on the level of Mein Kampf or Aesop’s Fables. It’s our view that is being critiqued and so we have the task of defending the Bible. And in order to do that one must cite it! Good grief . . .

The condescension towards the Apostle Paul, who was one of the most educated and philosophically nuanced men in the ancient world, and a brilliant writer is, of course, completely out of line and ridiculous; a quintessential example of atheist chronological snobbery.

For the outsider test to fail the test of the Bible you must first establish the trustworthiness of the Bible to tell us the truth. I’m proposing a test to see if the Bible should be trusted in the first place. How do YOU propose we test it? Could you please explain to me why you might use double-standards when testing it against other religious books?

That’s super-easy: we test it like any other source of history: through historiographical scholarship and archaeology. The Bible has been tested again and again in this fashion and has proven itself accurate, insofar as it reports historical, geographical, biographical details, etc.

Wholly apart from religious faith, then, we can establish that it is a remarkably accurate document that can be trusted to accurately report things. That’s the bare minimum. Once supernatural events are being discussed, the argument must be made on an entirely different plane: legal-historical evidences, philosophy, etc. But the Bible is not untrustworthy on the basis of inaccuracy of things that can be empirically verified.

That’s enough for now. If John wants to engage in further dialogue, minus the acrimony that has plagued our previous several attempts, I’d be happy to. Many areas here can be unpacked and elaborated upon in great depth.

[Loftus has never replied, these past almost eight years]