1. The bottom line is not “tradition vs. no tradition,” but rather, “true, apostolic tradition vs. false traditions of men.”

2. Tradition can’t be separated from the Bible; that would be like trying to separate hydrogen atoms from a water molecule.

3. I became a Catholic largely because Protestant innovations were merely the inventions of men. They had no pedigree in Church history, and thus, no reason to be accepted. [BCO, 113; modified]

4. Who determines which teachings are “traditions of men” and how? And why should we value their opinions or heed their authority more so than the venerable Fathers of the Church? [BCO, 113]

5. What we need to establish is: why is anything and everything that may have been passed down by the apostles, to be regarded as intrinsically questionable simply because it is not inspired Scripture?

6. If God can use sinners to write an inspired Bible, certainly He can use sinful men to proclaim infallible teachings in Tradition, as that is merely a protection from error, not a positive quality of inspiration.

7. Most early heresies (e.g., Monophysitism and Arianism), believed in sola Scriptura, and the Church refuted them by the method of “Bible-as-interpreted-by-apostolic-Tradition,” within the framework of apostolic succession. [BCO, 80; modified]

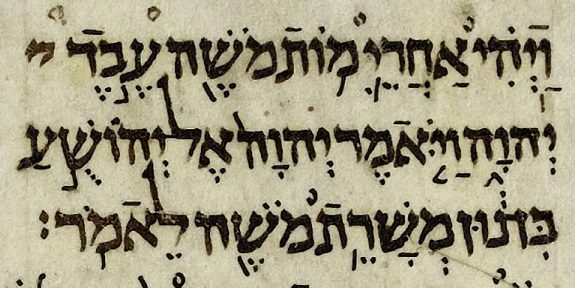

8. Jesus contrasts human tradition with the word of God in Mark 7:13, but that word of God is not only not restricted to the written Bible, but even identical to Divine Tradition, once one does some straightforward comparative exegesis.

9. The Bible points to an authoritative tradition and an authoritative Church (even to a papacy). It has apostolic succession; it has infallible councils. It has authoritative bishops. It’s all in there. Catholicism is biblical: far more than any form of Protestantism.

10. Peter in Acts 2, in his sermon in the Upper Room, and in other recorded sermons, gave an authoritative New Covenant interpretation of salvation history. It was binding before it became “inscripturated,” because it was from an apostle.

11. It is ludicrous to assume sola Scriptura, and then contend that the apostles always intended for subsequent Christian teaching after their deaths to be by the written word in the Bible alone, and never by oral or Church tradition, for the simple reason that this is never taught in Scripture.

12. When Peter interpreted Old Testament Scripture messianically and “Christianly,” in the Upper Room (as recorded in Acts 2), his word was just as authoritative and inspired as when it was set down in writing later. Throughout the book of Acts we see St. Peter and St. Paul exercising apostolic authority and preaching, not handing out Bibles.

13. The Bible itself speaks explicitly of both a true divine, “received” Tradition and of the binding authority of the universal, institutional Church, and the very canon (the “stuff”) of the Bible was authoritatively determined by the Church. Therefore, the three interrelated concepts cannot be separated, any more than can the three dimensions of a cube. [PRO, 9]

14. The Church Fathers always appealed not solely to Holy Scripture, but to the history of doctrine and apostolic succession, which for them was the clincher and coup de grace, in arguments against the heretics. Groups such as the Arians, on the other hand, believed in Scripture Alone, precisely because they couldn’t trace their late-arriving doctrines back past Arius (d.c. 336). [PRO, 14-15]

15. Jesus rejects only corrupt, human, Pharisaic tradition (paradosis: Mt 15:3,6, Mk 7:8-9,13), not Tradition per se, so this might be thought to be an indirect espousal of true apostolic Tradition. This is also the case with Paul in Colossians 2:8. The New Testament explicitly cites oral tradition in Matthew 2:23, 23:2, 1 Corinthians 10:4, 1 Peter 3:19, and Jude 9, in support of doctrine, and also elsewhere (2 Tim 3:8, Jas 5:17, Mt 7:12). [BCO, 87]

16. Scripture is unique, but it itself refers to an authoritative apostolic Tradition, which is not identical to itself (e.g., Jn 21:25; 1 Cor 11:2; 2 Thess 2:15; 3:6; 2 Tim 1:13-14; 2:2; 2 Pet 2:21). Apostolic Tradition and Scripture are harmonious, but they are not identical, and that being the case, sola Scriptura is demonstrated to be untrue. It’s as simple as that, but there are many other deficiencies in it as well. [BCO, 12]

17. Tradition, like the Bible, or Word of God, is also presented as immutable in Holy Scripture (in the sense that all truth is immutable), since it is spoken of as delivered “once and for all” to the saints (Jude 3). Likewise, 2 + 2 = 4 stands forever. So does a = a, and the theory of gravity (as long as this present universe exists). Every created soul, for that matter, “stands forever,” as they will never cease being. The preached gospel stood forever as truth before it was ever encapsulated in the Bible. [PRO, 15]

18. I’ve often noted how, in a single night of discussion, Jesus or Paul or other apostles passing along what they learned from Our Lord, could have easily spoken more words than we have in the entire New Testament. It’s fallacious to think that none of that had any effect on subsequent teaching (even Bible writing) of these same apostles and disciples. One can remember encounters like this with extraordinary people for a lifetime: at least the main ideas, if not all particulars.

19. Jesus Himself followed the Pharisaical tradition. He adopted the Pharisaical stand on controversial issues (Matthew 5:18-19, Luke 16:17), accepted the oral tradition of the academies, observed the proper mealtime procedures (Mark 6:56, Matthew 14:36) and the Sabbath, and priestly regulations (Matthew 8:4, Mark 1:44, Luke 5:4). Jesus’ condemnations were directed towards the Pharisees of the school of Shammai, whereas Jesus was closer to the school of Hillel.

20. A prophet’s inspired utterance was indeed the word of the Lord, but it obviously was not written as it was spoken! Most if not all prophecy was first oral proclamation, but it was just as binding and inspired as oral revelation, as it was in later written form (i.e., those prophecies which were finally recorded — surely there were more). In this sense truly inspired prophecies are precisely analogous to the proclamation of the gospel, or kerygma, by the apostles.

21. Protestants will acknowledge (often when pressed) that oral forms were “authoritative” before Scripture was compiled. But then, where in Scripture are we ever informed that oral tradition is to altogether cease after the canon is established? I agree that these oral transmissions do not detract from Scripture itself, but then I believe that legitimate (not corrupt or Pharisaical) tradition, whether oral or written, is consistent with Scripture – that they are two sides of a coin. [BCO, 26; modified]

22. Many Protestants axiomatically assume the (false) premise that the Bible precludes tradition. Therefore, they reason that in the opposite scenario of Tradition being present and authoritative, the Bible therefore necessarily becomes unnecessary. But that is no more true or biblical than its logical opposite. We crush this false dilemma by asserting that the Bible itself presupposes both tradition and the written revelation (as well as the Church) as normative at all times, and not in any way, shape, or form opposed to each other at all. [PRO, 15]

23. The apostolic deposit is not “secondary” material. It was received from Jesus, passed on to the apostles and in turn passed down by them. It expands upon what we know from Scripture, and is just as valid (in terms of truth, though not inspiration). True, one must determine precisely what constitutes the Tradition. That’s ultimately the job of the Church. Truth doesn’t have to always be in the Bible itself to be authoritative. It has to be apostolic and to have always been held implicitly or explicitly by the Church universal. What is apostolic always is in fact harmonious with biblical teachings. [BCO, 53]

24. There are a multitude of allusions and direct citations of the “deuterocanonical” (or so-called “apocryphal”) books in the New Testament. Since Protestants consider these non-inspired and thus not part of the Bible, to authoritatively cite them is, from their perspective, citing a purely non-biblical tradition. But Jesus and the Bible writers do this quite often, which goes to show that there is a much larger Christian tradition, than the Bible Alone (i.e., the latter as defined by Protestants, who deny that the deuterocanon is Scripture; for us, it is citing of Scripture, which is no problem at all).

25. A) All true tradition = Scripture.

B) Our preliminary adopted true tradition: A (upon which we base our overall notion of tradition, and which serves as our primary definition) is not found in Scripture.

C) But then it must be a false tradition, because it fails to meet its own (non-reasoned) assumed criterion of being in Scripture, which is tradition.

D) A false, self-defeating tradition clearly cannot be the basis of all true tradition.

E) Therefore the result that flows from an already self-defeating preliminary principle is itself self-defeating and therefore false.

F) Ergo, A must be rejected as irrational and self-contradictory.

Dave Armstrong, Bible Conversations: Catholic-Protestant Dialogues on the Bible, Tradition, and Salvation [BCO], Lulu, 2007.

Dave Armstrong, Protestantism: Critical Reflections of an Ecumenical Catholic [PRO], Lulu, 2007.