. . . Especially that of the Early Church, and the Jerusalem Council

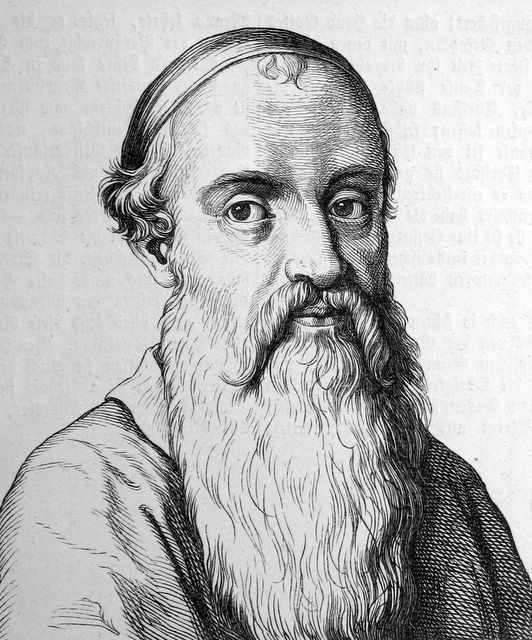

Menno Simons (1496-1561), founder of the Mennonites, from Two Hundred German Men in Portraits and Biographies, Leipzig 1854, edited by Ludwig Bechstein. Illustration by Hugo Bürkner (1818-1897) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

(5-30-12)

This exchange took place on Devin Rose’s blog, in the combox of his review of my book, 100 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura. Phil Wood is a Mennonite, and sometimes calls himself an Anabaptist as well. His words will be in blue. This dialogue is posted with Phil’s express permission.

* * *

Devin, as you know by now I’m no fan of Catholic/Protestant apologetic ping pong. I agree with your tack on this one for the first few steps, but part company half way through. It is quite right that Sola Scriptura is biblically untenable. I offer a loud ‘Amen’ to the role of the Church. Even a mainstream Conservative Evangelical scholar such as F.F. Bruce makes a cogent case for the importance of Tradition in ‘Scripture in Relation to Tradition and Reason’ (ed Dewery and Baukham, Scripture Tradition and Reason).

I do think you make a leap though, in assuming that ‘the Church’ is co-terminous with the views of the hierarchy. I’m coming at hermeneutics from below. I believe in a hermeneutic of peoplehood and (with Moltmann) that there is nothing higher than the congregation. The best example I can find of that perspective is found in John Howard Yoder, The Priestly Kingdom. I have also developed his theme of the ‘shape of conversation’.

I’m curious how this is squared with the Jerusalem Council in Scripture (Acts 15)? Are you saying that this council was strictly a temporary (and henceforth merely optional) expedient, and that St. Paul preached its results as binding (Acts 16:4), but then as history goes on all that is kaput and we go to a strictly congregational model?

That makes no sense to me. There is also all the scriptural data about Petrine primacy that seems to presuppose an overarching authority of one “super-bishop” and leader of the Church, so to speak. I lay that evidence out most succinctly in my “50 New Testament Proofs for the Primacy of Peter”.

I am somewhat surprised that you should use the example of the Council of Jerusalem. Of Peter, Paul and James it is the latter who takes the lead role. Acts 15:22 makes explicitly shows ‘the whole church’ engaged in the decision-making.

I followed your link. My overall sense is that you are seeking biblical precedent to bolster the authority claims of a contemporary institution (i.e. it’s anachronistic). Petrine primacy is a phrase from a later period. As far as we know it was Clement of Rome who first used the term ‘lay’ to mean a non-minister in A.D.96. The idea of priestly ordination wasn’t fully complete until the 5th Century (as Herbert Haag points out).

Congregationalism makes far more modest claims. One of the few passages in the Gospels which mentions ‘church’ (Matt 18.15-20) follows the rabbinic precedent of binding and loosing, focusing on ethical reasoning, pastoral care and conciliation. Where two or three gather together in the name of Christ, there Christ is present (Matt 18.20). I see no mention of clergy or super-bishops.

You didn’t reply to my direct questions; instead heading off onto various rabbit trails, of varying degrees of irrelevance; therefore I won’t answer yours (too busy anyway to get into this in depth today). It so happens that I just cited one of my arguments in the book in another discussion that had to do with the Jerusalem Council. I’ll quote it here again (slightly different from the book, as it is my final manuscript):

74. Paul’s Apostolic Calling Was Subordinated to the Larger Church and Was in Harmony with Peter

Paul’s ministry was not “self-validating.” He was initially commissioned by Peter, James, and John (Gal 2:9) to preach to the Gentiles. After his conversion, he went to Jerusalem specifically to see Peter (Gal 1:18). In Acts 15:2-3 we are told that “Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the elders about this question. So, being sent their way by the church,” they went off on their assignment.

That is hardly consistent with the idea of Paul being the “pope” or leading figure in the hierarchy of authority; he was directed by others, as one under orders. When we see Paul and Peter together in the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15:6-29), we observe that Peter wields an authority that Paul doesn’t possess.

We learn that “after there was much debate, Peter rose” to address the assembly (15:7). The Bible records his speech, which goes on for five verses. Then it reports that “all the assembly kept silence” (15:12). Paul and Barnabas speak next, not making authoritative pronouncements, but confirming Peter’s exposition, speaking about “signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles” (15:12). Then when James speaks, he refers right back to what “Simeon [Peter] has related” (15:14). Why did James skip right over Paul’s comments and go back to what Peter said? Paul and his associates are subsequently “sent off” by the Council, and they “delivered the letter” (15:30; cf. 16:4).

None of this seems consistent with the notion that Paul was above or even equal to Peter in authority. But it’s perfectly consistent with Peter’s having a preeminent authority. Paul was under the authority of the council, and Peter (along with James, as the Bishop of Jerusalem) presided over it. Paul and Barnabas were sent by “the church” (of Antioch: see 14:26). Then they were sent by the Jerusalem Council (15:25, 30) which was guided by the Holy Spirit (15:28), back to Antioch (15:30).

Just one more thing:

Acts 15:22 makes explicitly shows ‘the whole church’ engaged in the decision-making.

Yes, of course; but so what? This is the Catholic model: ecumenical councils make decisions (led and guided by the Holy Spirit), in tandem with the popes who preside and have “veto power.” It’s both/and.

The Council spoke for and to the entire Church. This is the whole point. Paul then proclaimed its edicts (in other regions; in this case, Asia Minor or modern-day Turkey, which was quite a ways away) as binding and obligatory upon all (Acts 16:4: “for observance”). If you want to say James was top dog at the council, fine. Even on that view, he is being a bishop (of Jerusalem), and presiding over a council that makes binding legal decisions, obligatory on all Christians everywhere. That ain’t congregationalism, sorry; it’s not even Presbyterianism [i.e., that form of Church government]. It is clearly episcopal / Catholic ecclesiology.

This precisely contradicts some notion of local congregationalism only. The problem is with your view of ecclesiology, not ours. Hence, you sidestepped the relevant issue and went into diverting side-issues.

Perhaps you didn’t intend to (people often wander off-topic to the detriment of constructive discourse and dialogue), but that was the result.

Dave,as I began by original contribution to this thread by expression disdain for ping pong I’m not going to go down the route of you say black and I say white. I think you’re beating the text into shape to make it serve the truth claims of a clerical elite. I’m a Mennonite writing from a UK and not a US context. Frankly, after thousands of years of Christendom truimphalism we have had enough of hierarchical church structures and forms of argumentation that resort to ‘our bishop is more purple than yours’.

Why comment at all, then, Phil, if you’re not willing to subject your positions to scrutiny and defend them? I don’t write this in any anger whatsoever, but in perfect calmness, and with true befuddlement. I always marvel at people who want to take their potshots at other views; then when challenged back, appeal to a calm, “above the fray” non-involvement ethos, as if their initial comments were not getting involved in the discussion.

So you were involved in this thread, but really not. You entered the discussion but in fact never did . . . I can’t be faulted for simply responding to your critique, in any event.

Hi Dave, I apologize if I was unclear. I’m looking over what I said in my previous comment and I agree with you; it’s inconsistent. I suspect the business of arguing back and forth, point by point would take up more time than either of us have. I’m in something of a cleft stick where this blog is concerned, as Devin knows from my previous comments. Fundamentally I don’t believe apologetics is an appropriate form of Christian communication. I am very much an unreconstructed liberal wishing for the good old days of enthusiastic ecumenism. At the same time, I think it’s important for Christians of different traditions not to retreat into our comfort zones.

There are clearly disagreements between us. Broadly, I believe we have stumbled over centuries of scaffolding and encrustation where the ‘Council of Jerusalem’ is concerned. The phrase ‘Council of Jerusalem’, is after all a later interpretation of what went on. I am wary of attempts to impose a model (e..g. the Calvinist fourfold ministry) on a 1st Century picture than was almost certainly far more fluid and eclectic than attempts at systematization allow.

My sense of ‘befuddlement’ lies mainly in why it should matter so much to ‘prove’ Petrine Primacy. Is this a way of arguing us back to Rome? What is your objective?

Fair enough. I appreciate the clarification.

I’m as ecumenical as you are, which is why I just completed the book, The Quotable Wesley: presently under serious consideration by a Protestant publisher. There is no fundamental conflict between ecumenism and apologetics, though for some odd reason lots of folks seem to think there is.

Last Friday we had a very friendly discussion at my house with three atheists (one the main presenter) and about a dozen Catholics. That’s about as ecumenical as it gets, I think.

I agree that there was fluidity in early ecclesiology, and stated that in my first book, written in 1996. We would fully expect this, because ecclesiology developed, just as all theology did. That said, the outlines of the later episcopal structure of Christian government is remarkably evident in the New Testament. See my Appendix Two from A Biblical Defense of Catholicism: The Visible, Hierarchical, Apostolic Church.

Apologetics is thoroughly biblical, as I have, I think, demonstrated many times. “Contend earnestly for the faith” (Jude 3). “Stand ready to make a defense [apologia] for the hope that is in you” (1 Peter 3:15). Paul argued and disputed endlessly with Jews and Greeks; he didn’t simply preach. Jesus argued with Pharisees, and engaged and challenged them. Paul defended his Christian views at great length at his trial. It’s all very biblical. In fact, the word apologia is the same one that was the title of Plato’s famous book, detailing Socrates’ defense of himself at his own trial.

My “objective” (since you asked) is to seek truth and follow it wherever it leads. Period. End of story. I defend what I believe to be the fullness of Christian truth (Catholicism) because I think it is better to reside in the fullness than not to: that truth (along with love) is a wonderful, godly end that all should seek with all their might. We all [should] proclaim and defend what we believe in good faith to be true. If I am convinced that the fullness of truth lies elsewhere, then I surely will move to that position, just as I moved from religious nominalism / paganism to evangelicalism, and from that to Catholicism.

It’s all by God’s grace. I proclaim and defend, as an apologist / evangelist. God moves hearts as He wills, and as human free will allows, in cooperation with God’s grace. But (like Paul) “woe to me if I preach not the gospel” because this is my calling.

Is it okay with you if I put our dialogue on my blog (it’s already public here, anyway)? I can include your name or not, as you wish. I think it is an exchange that might be of some value to others. I am a great advocate of putting up dialogues and letting people decide where truth lies.

Dave, you are welcome to include the dialogue on your blog. It may also give me an opportunity to contribute in some more detail on some of the knotty ecclesiology we have touched on. I’ll place your blog on my blogroll. It’s an interesting discussion, partly because I’m not coming at this from a mainstream Protestant perspective.

As for Apologetics, I entirely agree with your helpful biblical summary. Where I have concerns lies in interface between Apologetics and ecumenism. I have a strong sense, in talking to some Traditionalist Catholic interlocutors, that Apologetics have supplanted ecumenism. As you will gather from my own blog (and blogroll) I have an extensive range of Catholic contacts. My wife Anna is Roman Catholic. I wish you well with the writing. I also have a book in process at present – The Gospel of Slow.

I sometimes wonder why I have stuck with this blog for so long. In large part it’s because I have always found Devin gracious and fair. To be honest, some of the discussion has been bruising, because I’m frequently expressing a minority viewpoint. God forbid, five hundred years after the Reformation, that disunity should ever be seen as ‘normal’. Speaking as an Anabaptist can be a painful in-between place – as Walter Klaasen said, ‘neither Catholic nor Protestant’. I believe there is something in that experience of value across the ecumenical spectrum, as all of us encounter a sense of loss and marginality after Christendom.

If you’d like to continue the discussion, that would be great. From where I sit, the “hard questions” I asked about the Jerusalem Council still remain to be dealt with. I’m curious how an advocate of congregational government would answer those. You can always concede that you don’t have any answers to my questions; that’s fine, too. :-)

Dave, as I am heading off to Strasbourg tomorrow in connection with Mennonite Central Committee responsibilities, I shall try to keep this succinct. You should be aware that I am a British Mennonite and that there is considerable variety amongst Mennonites in terms of polity. Overall, I think it would be true to say that Mennonites in particular and Anabaptists in general have congregational DNA. Whilst it is true that local congregations are self-governing, strong inter-Mennonite institutions such as the Mennonite Central Committee and the Mennonite Mission Network act as a counterpoint and ensure that congregations have a view beyond the local and are able to act in concert.

Sort of like Baptists or evangelicals, who form overarching associations of varying governing or at least significantly guiding force . . .

I do not believe that there is a single New Testament leadership model. Over the past two thousand years Christianity has existed in many forms – fusions of cultural, pragmatic and biblical concerns. This does not mean that the New Testament is exegetically unintelligible. In response to your suggested ‘hard question’ I do wonder how you would address the open multi-voiced mutuality of 1 Cor 12-14, for example.

Well, again, that is not responding to my question; it is simply asking a different one of your own (that you think runs counter to my assumptions). But I do directly respond to questions, so here I go:

These three chapters, first of all, indicate a strong central authority, since it is the apostle Paul giving all of these rather obligatory instructions (see, e.g., 1 Cor 11:2 and 23, where Paul refers to traditions he received and delivered, to be followed). At the time, remember, it was simply a letter, and not known to be Scripture. So there is your authority. Paul is writing to the Corinthians, but that is only one church of many that he oversees and guides.

This is apostolic authority, and to the extent that it continues to be a model and binding today, it remains apostolic authority, now encapsulated in Scripture. Peter does the same thing in his letters, and he doesn’t even narrow them down to one congregation. Both of those phenomena are strongly indicative of the later more fully-developed episcopacy with a pope leading.

You call this “mutuality”. But I see strong central authority far more akin to Catholicism than Anabaptism or wider Protestant sectarianism and denominationalism with a congregational notion of governance. Paul details a clear hierarchy of authority and (“higher”) gifts in 12:28-31, mentioning apostles, prophets, teachers: not all fit in every category (is his point in 15:29-30). Thus, hierarchy . . .

Most of the material Paul deals with here has to do with worship practices, which can vary widely according to time and place, and which are not doctrines or dogmas, strictly speaking. Nothing here goes against the Catholic model, so it is mostly irrelevant to our discussion.

Turning to the so-called ‘Council of Jerusalem’,

This is one of the curiosities of your view: the reluctance to call a thing what it is. I was unaware that this was some controversial thing (and certainly not a position confined to those who hold to episcopal ecclesiology). For example:

The first council of the Church was that described in Acts 15.

(Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, edited by F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone, 2nd edition, Oxford Univ. Press, 1974; p. 351: “Council”)

The Council of Jerusalem is the name commonly given to the meeting convened between delegates form the Church of Antioch (led by Paul and Barnabas) and the apostles and elders of the Church of Jerusalem . . .

(New Bible Dictionary, edited by J. D. Douglas, Eerdmans, 1962; p. 263: “Council, Jerusalem”)

The Bible seems clear enough to me:

Acts 15:6 (RSV) The apostles and the elders were gathered together to consider this matter.

Apostles and elders gathered together to discuss doctrinal issues and issue binding decrees is not a council? That’s odd. What is it then? A pow-wow? A campfire meeting with a singalong? A Sunday get-together after church with (beef) hot dogs?

One of my “hard questions” that you have chosen not to respond to directly was the following:

Paul then proclaimed its edicts (in other regions; in this case, Asia Minor or modern-day Turkey, which was quite a ways away) as binding and obligatory upon all (Acts 16:4: “for observance”). If you want to say James was top dog at the council, fine. Even on that view, he is being a bishop (of Jerusalem), and presiding over a council that makes binding legal decisions, obligatory on all Christians everywhere.

If you want to say it is merely a local council of Jerusalem (F. F. Bruce takes that view), then how is it that Paul acts as he does above, in Asia Minor? How can the Jerusalem Church have jurisdiction over those Christians unless episcopalian government is in place?

Moreover, the biblical text informs us that a letter was written to “the brethren who are of the Gentiles in Antioch and Syria and Cili’cia” (Acts 15:23). It is written in the language of command (though gently so):

Acts 15:28-29 For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: [29] that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity. If you keep yourselves from these, you will do well. Farewell.

How is it that one local church in Jerusalem (according to your view) can give “binding orders” to other local churches far away? That is nonsensical in a congregational interpretation. But it makes perfect sense with an episcopal or even papal / Catholic view.

I begin by saying that there is no evidence that there was some superior organizational level to which local congregations are accountable.

I just gave an example (a pretty compelling one, in my opinion) of why I think this perspective is biblically untenable.

There is no indication that this gathering should be be taken as a standing paradigm for wider authority.

Again, if it shows a “higher” church authority giving binding decisions to Christians over wide geographical areas, then it is a model, by common sense. Otherwise, why is it included in revelation? These things are in Scripture for our instruction. It’s not just the council, but also Peter and Paul exercising apostolic (and papal) authority.

In fact the use of the word ‘Council’ is potentially misleading. We tend to think of ‘Ecumenical Councils’ and so on. Paul and Barnabas didn’t go to Jerusalem to get a ruling on the issue. This was straightforward fraternal contact between two churches over a pressing matter of mutual concern.

That’s not what I see in the text:

Acts 15:2 And when Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with them, Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the elders about this question.

The ruling came in Acts 15:22-29. Paul them “delivered them for observance” in Asia Minor. This is exactly how Catholicism works: an ecumenical council takes place (Vatican II: in my lifetime), and I am to receive the instruction from it in Detroit, Michigan, since it applies to all Catholics.

Elsewhere in the New Testament ethical reasoning (i.e. binding and loosing) is practiced by the local church body rather than by elders or bishops (see Matt 18:15-17).

That’s right. We believe it is exercised by every priest, and that is local. However, there is also a sense in which Peter and his successors can bind and loose for the entire Church. I have detailed many Protestant commentators writing about this, in my book on Catholic ecclesiology. For example:

And what about the “keys of the kingdom”? The keys of a royal or noble establishment were entrusted to the chief steward or majordomo; he carried them on his shoulder in earlier times, and there they served as a badge of the authority entrusted to him. About 700 B.C. an oracle from God announced that this authority in the royal palace in Jerusalem was to be conferred on a man called Eliakim . . . (Isa. 22:22). So in the new community which Jesus was about to build, Peter would be, so to speak, chief steward.

(F. F. Bruce, The Hard Sayings of Jesus, Downers Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 1983, 143-144)

In Matthew 16:19 it is presupposed that Christ is the master of the house, who has the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, with which to open to those who come in. Just as in Isaiah 22:22 the Lord lays the keys of the house of David on the shoulders of his servant Eliakim, so Jesus commits to Peter the keys of his house, the Kingdom of Heaven, and thereby installs him as administrator of the house.

What do the expressions “bind” and “loose” signify? According to Rabbinical usage two explanations are equally possible: “prohibit” and “permit”, that is, “establish rules”; or “put under the ban” and “acquit.”

(Oscar Cullmann, Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr, translated by Floyd V. Filson, Philadelphia: Westminster, 1953, 203-205)

These terms [binding and loosing] thus refer to a teaching function, and more specifically one of making halakhic pronouncements [i.e., relative to laws not written down in the Jewish Scriptures but based on an oral interpretation of them] which are to be ‘binding’ on the people of God. In that case, Peter’s ‘power of the keys’ declared in [Matthew] 16:19 is not so much that of the doorkeeper, who decides who may or may not be admitted to the kingdom of heaven, but that of the steward . . . . whose keys of office enable him to regulate the affairs of the household. . . . [Isaiah 22:22 is] generally regarded as the Old Testament background to the metaphor of keys here. . . .

(R. T. France, Matthew: Evangelist and Teacher, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1989, 247)

In the . . . exercise of the power of the keys, in ecclesiastical discipline, the thought is of administrative authority (Is 22:22) with regard to the requirements of the household of faith. The use of censures, excommunication, and absolution is committed to the Church in every age, to be used under the guidance of the Spirit . . .

So Peter, in T.W. Manson’s words, is to be ‘God’s vicegerent . . . The authority of Peter is an authority to declare what is right and wrong for the Christian community. His decisions will be confirmed by God’ (The Sayings of Jesus, 1954, p. 205).

(New Bible Dictionary, edited by J. D. Douglas, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1962, 1018)

It was a local church that commissioned Paul and Barnabas (Acts 13.1-3).

That’s a partial truth, but not the whole truth. From chapter three of my book, mentioned above:

He [Paul] went to see St. Peter in Jerusalem for fifteen days in order to be confirmed in his calling (Gal 1:18), and fourteen years later was commissioned by Peter, James, and John (Gal 2:1-2, 9). He was also sent out by the Church at Antioch (Acts 13:1-4), which was in contact with the Church at Jerusalem (Acts 11:19-27). Later on, Paul reported back to Antioch (Acts 14:26-28).

Acts 15:2 states: “. . . Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to the apostles and the elders about this question.” The next verse refers to Paul and Barnabas “being sent on their way by the church.” St. Paul did what he was told to do by the Jerusalem Council (where he played no huge role), and Paul and Barnabas were sent off, or commissioned by the council (15:22-27),. . .

In Galatians 1-2 Paul is referring to his initial conversion. But even then God made sure there was someone else around, to urge him to get baptized (Ananias: Acts 22:12-16). He received the revelation initially and then sought to have it confirmed by Church authority (Gal 2:1-2: “. . . I laid before them . . . the gospel which I preach among the Gentiles, lest somehow I should be running or had run in vain”); then his authority was accepted or verified by James, Peter, and John (Gal 2:9). . . .

In Galatians 1:8-9 Paul tells the Galatians to reject any gospel that is different from what he presented to them. He preached the truth to them. In the same book, however, he says how this gospel had been confirmed as true by the Church (Gal 1:18; 2:1-2, 9). No opposition between Paul and the apostolic tradition and gospel of the Church is present in these biblical texts. The Church is guided by God to preserve apostolic truth. St. Paul is in communion with this same Church, and obedient to her.

Whatever the unevenness of the biblical text, I believe Congregationalism best expresses the dynamic open process described in 1 Cor 12-14.

And I believe Catholicism best reflects the overall biblical picture (all things considered). I have stated why I don’t think 1 Cor 12-14 is decisive for your side.

I am quite aware of Episcopal and Presbyterian objections to a congregational approach. There is clearly, for example, evidence of the influence of the Jewish synagogical model on early churches. So, I am not arguing that the New Testament is a ‘flat’ text. There is, for example, clearly a change of temperature with the Pastoral Epistles.

I’d love to see how you would reply to my arguments above.

Behind the scenes of our discussion is a broader question that relates to change and continuity in the Christian tradition. Is it possible for example for the church to ‘fall’ so that restitution is required. Luther drew back from that position but the Radical Reformers carried in through.

Luther was more correct. It is biblically, historically, and logically absurd to posit a Church that initially was in God’s grace and then entirely fell away. Most of the biblical arguments for this position of mine is detailed in my book on the Church and papacy (I can send you a free PDF if you like), but there is some in a dialogue I had with a Lutheran.

Whatever the variations in the biblical record, we continue to argue strongly that what the Church became under Constantine was an aberration.

Not at all. There was a lot of caesaropapism in the east, but the papal model is already strongly indicated in the Bible (my 50 NT Proofs that you passed by without comment), so that Church history merely develops that kernel.

This is why Anabaptists regard our peace testimony and open, congregational process as in some sense, a ‘looping back’ to Christian origins. I offer two reflections on restitution by way of starting points for further discussion [one / two].

I read those; thanks. I didn’t see much of direct relevance to this discussion, though.

* * *