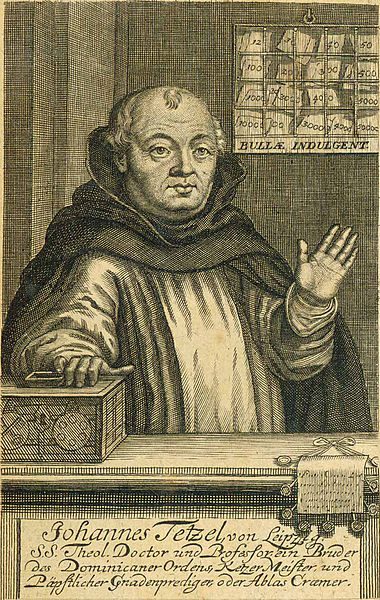

Johann Tetzel (1465-1519): the German Dominican friar who was a central figure in the “Reformation” debate about indulgences and their abuses [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

[see the related paper, Biblical Evidence for Indulgences, for necessary background on how the Catholic Church defines an indulgence]

*****

In his book, The Question Box (New York: Paulist Press, 1929, 296-297). Bertrand Conway writes of the controversial history of indulgences:

Catholic historians — Gasquet, Pastor, Janssen, Michaels, Paulus — have frequently mentioned the abuses connected with the preaching of Indulgences in the Middle Ages. The medieval pardoner . . . was often an unscrupulous rascal, whose dishonesty and fraud were condemned by the Bishops of the time. We find orders for their arrest in Germany at the Council of Mainz in 1261, and in England by order of the Bishop of Durham in 1340. To indict the Church for these abuses . . . is manifestly dishonest . . .

It is comparatively easy today to get monies for any charitable enterprise, for we can appeal to thousands by letter, post, radio or the daily press. In the Middle Ages, when men wished to build a church or support a worthy charity, the Bishop or Pope granted an Indulgence, which first of all called upon the people to approach the Sacraments of Penance and the Eucharist, and then ‘to lend a helping hand’ in some special work of charity. The Council of Trent, following the Councils of Fourth Lateran [1215], Lyons [1245 and 1274] and Vienne [1311-12], condemned in express terms ‘the wicked abuse of quaestors of alms,’ and, because of the great scandal they had given, ‘abolished their name and use’ (Session 24).

While Catholics believe that the building of St. Peter’s in Rome was a matter of interest to the whole Catholic world, they heartily condemn with Grisar and Janssen [Catholic historians] the manner of financing the Indulgence, and the exaggerations of the preachers in extolling unduly its effects and privileges.

. . . As both Pastor and Grisar point out, we must carefully distinguish between Tetzel’s teaching with regard to Indulgences for the living, and Indulgences applicable to the dead. With regard to Indulgences for the living, his teaching, as we know from his Vorlegung and his Frankfort Theses, was perfectly Catholic . . .

Cardinal Cajetan at the time condemned Tetzel’s opinion [regarding the dead], and taught that ‘while we may presume in a general way that God is willing to accept Indulgences for the dead, we have no certainty whatever that He does so in any particular case. That is the secret of God alone.’ In 1477 Pope Sixtus IV had expressly taught that the Church applies Indulgences for the dead ‘by way of suffrage,’ for the souls in Purgatory are no longer subject to her jurisdiction. They receive Indulgences not directly, but indirectly, through the intercession of the living.

Likewise, German Catholic historian of the papacy, Ludwig von Pastor (1854-1928) explains, carefully distinguishing where Tetzel’s teaching was dead-wrong, and where it was actually in accordance with Catholic teaching:

Above all, a most clear distinction must be made between indulgences for the living and those for the dead.

As regards indulgences for the living, Tetzel always taught pure (Catholic) doctrine. The assertion that he put forward indulgences as being not only a remission of the temporal punishment of sin, but as a remission of its guilt, is as unfounded as is that other accusation against him, that he sold the forgiveness of sin for money, without even any mention of contrition and confession, or that, for payment, he absolved from sins which might be committed in the future. His teaching was, in fact, very definite, and quite in harmony with the theology of the (Catholic) Church, as it was then and as it is now, i.e., that indulgences “apply only to the temporal punishment due to sins which have been already repented of and confessed” ….

The case was very different with indulgences for the dead. As regards these there is no doubt that Tetzel did, according to what he considered his authoritative instructions, proclaim as Christian doctrine that nothing but an offering of money was required to gain the indulgence for the dead, without there being any question of contrition or confession.

He also taught, in accordance with the opinion then held, that an indulgence could be applied to any given soul with unfailing effect. Starting from this assumption, there is no doubt that his doctrine was virtually that of the well known drastic proverb.

The Papal Bull of indulgence gave no sanction whatever to this proposition. It was a vague scholastic opinion, rejected by the Sorbonne in 1482, and again in 1518, and certainly not a doctrine of the Church, which was thus improperly put forward as dogmatic truth. The first among the theologians of the Roman court, Cardinal Cajetan, was the enemy of all such extravagances, and declared emphatically that, even if theologians and preachers taught such opinions, no faith need be given them. “Preachers,” he said, “speak in the name of the Church only so long as they proclaim the doctrine of Christ and His Church; but if, for purposes of their own, they teach that about which they know nothing, and which is only their own imagination, they must not be accepted as mouthpieces of the Church. No one must be surprised if such as these fall into error.

(The History of the Popes, from the Close of the Middle Ages, Ralph Francis Kerr, editor, 1908, B. Herder, St. Louis, Volume 7 [available online], 347–348)

*****

[see the related paper, Biblical Evidence for Indulgences, for background on how the Catholic Church defines an indulgence]

*****

Meta Description: Brief exposition on some of the myths & legends surrounding the Catholic practice of indulgences: particularly in the Middle Ages.

Meta Keywords: indulgences, communion of saints, penance, mortification, asceticism, Johann Tetzel, merit, intercession, intercession of saints, absolution, forgiveness of sins, temporal punishment, prayer