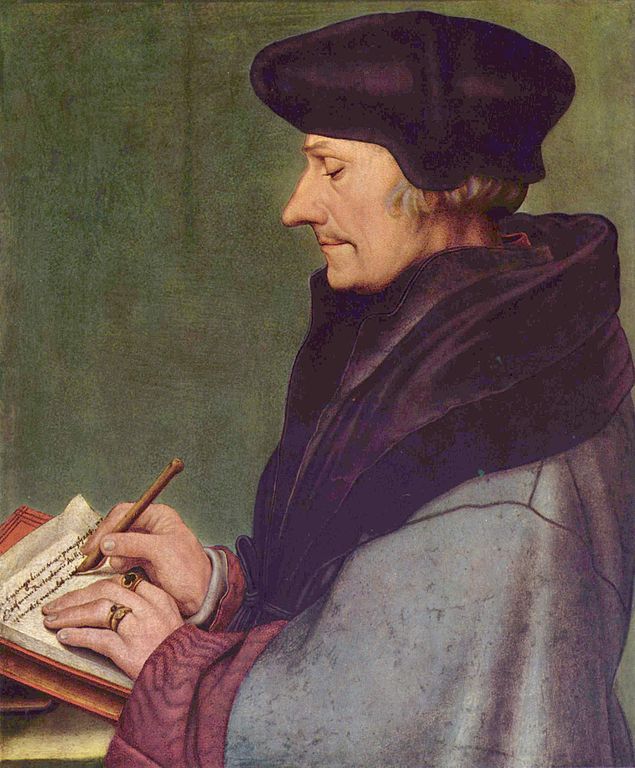

Desiderius Erasmus (1466/1469-1536); portrait (1523) by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498-1543) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

From: Peter Macardle and Clarence H. Miller, translators, Charles Trinkhaus, editor, Collected Works of Erasmus, Vol. 76: Controversies: De Libero Arbitrio / Hyperaspistes I, Univ. of Toronto Press, 1999.

* * * * *

I myself prefer to have this cast of mind than that which I see characterizes certain others, so that they are uncontrollably attached to an opinion and cannot tolerate anything that disagrees with it, but twist whatever they read in Scripture to support their view once they have embraced it. (p. 120; citing his earlier Discussion, or Diatribe)

I do not condemn those who teach the people that free will exists, striving together with the assistance of grace, but rather those who discuss before the ignorant mob difficulties which would hardly be suitable in the universities. . . . to discuss those difficulties of the scholastics about notions, about reality and relations, before a mixed crowd, you should consider how much good it would do. (p. 123)

And then, as for what you say about the clarity of Scripture, would that it were absolutely true! But those who laboured mightily to explain it for many centuries in the past were of quite another opinion. (p. 129)

But if knowledge of grammar alone removes all obscurity from Sacred Scripture, how did it happen that St. Jerome, who knew all the languages, was so often at a loss and had to labour mightily to explain the prophets? Not to mention some others, among whom we find even Augustine, in whom you place some stock. Why is it that you yourself, who cannot use ignorance of languages as an excuse, are sometimes at a loss in explicating the psalms, testifying that you are following something you have dreamed up in your own mind, without condemning the opinions of others? . . . Finally, why do your ‘brothers’ disagree so much with one another? They all have the same Scripture, they all claim the same spirit. And yet Karlstadt disagrees with you violently. So do Zwingli and Oecolampadius and Capito, who approve of Karlstadt’s opinion though not of his reasons for it. Then again Zwingli and Balthazar are miles apart on many points. To say nothing of images, which are rejected by others, but defended by you, not to mention the rebaptism rejected by your followers but preached by others, and passing over in silence the fact that secular studies are condemned by others but defended by you. Since you are all treating the subject matter of Scripture, if there is no obscurity in it, why is there so much disagreement among you? On this point there is no reason for you to rail at the wretched sophists: Augustine teaches that obscurity sometimes arises from unknown or ambiguous words, sometimes from the nature of the subject matter, at times from allegories and figures of speech, at times from passages which contradict one another, at least according to what the language seems to say. [De doctrina christiana 2.6.7, 2.9.15] And he gives the reason why God wished such obscurity to find a place in the Sacred Books. [De doctrina christiana 4.8.22] (pp. 130-131)

Furthermore, where you challenge me and all the sophists to bring forward even one obscure or recondite passage from the Sacred Books which you cannot show is quite clear, I only wish you could make good on your promise! We will bring to you heaps of difficulties and we will forgive you for calling us blinder than a bat, provided you clearly explicate the places where we are at a loss. But if you impose on us the law that we believe that whatever your interpretation is, that is what Scripture means, your associates will not put up with such a law and they stoutly cry out against you, affirming that you interpret Scripture wrongly about the Eucharist. Hence it is not right that we should grant you more authority than is granted by the principal associates of your confession. (p. 132)

. . . how did it happen that after the gospel was preached such blindness remained in the church of God that there was no one after the apostles except Jan Hus and Wyclif who did not get stuck in places all through the Scriptures? (p. 133)

. . . even your own writings and your dissenting adherents refute what you assert. (p. 134)

Nor did I say that some places in Scripture offer difficulties in order to deter anyone from reading it, but rather to encourage readers to study it acutely and to discourage the inexperienced from making snap judgments. (p. 135)

But still, if I were growing weary of this church, as I wavered in perplexity, tell me, I beg you in the name of the gospel, where would you have me go? To that disintegrated congregation of yours, that totally dissected sect? Karlstadt has raged against you, and you in turn against him. And the dispute was not simply a tempest in a teapot but concerned a very serious matter. Zwingli and Oecolampadius have opposed your opinion in many volumes. And some of the leaders of your congregation agree with them, among whom is Capito. Then too what an all-out battles was fought by Balthazar and Zwingli! I am not even sure that there in that tiny little town you agree among yourselves very well. Here your disciples openly taught that the humanities are the bane of godliness, and no languages are to be learned except a bit of Greek and Hebrew, that Latin should be entirely ignored. There were those who would eliminate baptism and those who would repeat it; and there was no lack of those who persecute them for it. In some places images of the saints suffered a dire fate; you came to their rescue. When you book about reforming education was published, they said that the spirit had left you and that you were beginning to write in a human spirit opposed to the gospel, and they maintained you did it to please Melanchthon. A tribe of prophets has risen up there with whom you have engaged in most bitter conflict. Finally, just as every day new dogmas appear among you, so at the same time new quarrels arise. And you demand that no one should disagree with you, although you disagree so much among yourselves about matters of the greatest importance! (pp. 143-144)

If you agreed among yourselves on your dogmas, you could accuse me of pride for not paying attention to teachings propounded by learned men with such an overwhelming consensus. As it is, since I have always adhered to the Catholic church and kept away from your fellowship, since your doctrine has been condemned by the princes of the church and the monarchs of the world, to say nothing of the censure by the universities, since you quarrel so much among yourselves, each of you claiming all the while to have the Spirit of Christ and a completely certain knowledge of Holy Scripture, how can you still . . . be outraged that an old man like me who knows nothing of theology should prefer to follow the authoritative consensus of the church rather than to join you, who dissent no less from the church than you dissent from each other? (p. 144)

Certainly no one after the apostles claimed that there was no mystery in Scripture that was not clear to him. (pp. 153-154)

Just so you, Luther, teach that whatever questions arise out of Holy Scripture ought to be handled in the presence of any person whatsoever . . . certain points . . . though they are true, can still not be spoken of before just any audience without endangering piety and concord and which should be set forth prudently. And here I place many points which you publish in the German language for uneducated people, such as the liberty of the gospel, which, if treated in judicious sermons on the right occasion, are not fruitless, but if they are treated in such sermons as yours, you see what fruit they produce. (pp. 166-167)

. . . even though I were to grant that what you teach is true, judge for yourself what contribution to piety is made by those who proclaim to the ignorant mob such things as these: there is no free will; our will has no effect but rather God works in us both our good deeds and our bad ones. (p. 167)

. . . it is possible that certain things may be in some sense true which nevertheless it would be inexpedient to proclaim before an unlearned audience. (p. 168)

. . . you offend precisely in that you continually foist off on us your interpretation as the word of God . . . in interpreting Scripture I prefer to follow the judgment of the many orthodox teachers and of the church rather than that of you alone or of your few sworn followers . . . (pp. 180-181)

And so away with this ‘word of God, word of God.’ I am not waging war against the word of God but against your assertion; nor is the word of God inconsistent with itself but rather human interpretations collide with one another. If you are influenced by the judgment of the church, what you assert is human fabrication, what you fight against is the word of God. (p. 181)

I say that those who treat such questions with arguments pro and con before an ignorant mob are like actors who perform a play not suited to everyone before an indiscriminate audience. (p. 195)

Holy Scripture, together with its figures of speech, has a language peculiar to itself. . . . just as the divine wisdom tempers its speech according to our feelings and our capacity to understand, so too the dispenser of Holy Scripture accommodates his language to the benefit of his audience . . . who ever conceded to you that figures of speech in Holy Scripture are not at all obscure as long as grammar is available, since everywhere in Genesis we are tormented by figures and the most erudite men sweat so much over the allegories of the prohets? (pp. 195-196)

But what I was after was for you to tell how we could be sure that what your adherents claim for themselves is true, especially when we see those who struggle equally to claim the Spirit for themselves disagree so violently among themselves about so many things. An easy believer is light-headed, and you would rightly find us lacking in manly constancy if we rashly defected from the universal Catholic church unless the matter was proved to us with ironclad arguments. (p. 199)

You stipulate that we should not ask for or accept anything but Holy Scripture, but you do it in such a way as to require that we permit you to be its sole interpreter, renouncing all others. Thus the victory will be yours if we allow you to be not the steward but the lord of Holy Scripture. (pp. 204-205)

. . . if they [bishops or theologians] should agree among themselves in explaining Holy Scripture, we would have something certain to follow. As it is, our heralds teach something different than you do, and your adherents disagree among themselves and even go so far as to cry out boldly against you. Where, then, even in the church, is this certain judgment by which we prove or disprove teachings drawn from Holy Scripture, a rule which is completely certain . . .? (p. 215)

. . . the second chapter of Malachi [verse 7] commands the people to ask for the Law from the mouth of a priest . . . Why then do you people not follow the advice of Malachi and ask for the Law from the mouths of priests and bishops? Moreover, what need was there to learn the Law from the mouth of a priest, since anyone of the people who knew the language and had common sense could easily understand a Law that was perfectly clear. [?] Therefore someone who orders that the Law be sought from the mouth of a priest indicates that the Law is not clear to just anyone, but rather he points out the fitting interpreter of the Law. (p. 217)

And why do we speak of the light of the gospel, if not because what is wrapped and covered up in figures in the Law is brought out into the open by the gospel? Is nothing there predicted about Christ which is not perfectly clear to all, provided they know Hebrew? Indeed, even the disciples of the Lord, after hearing so many sermons, after seeing so many miracles, after so many signs and tokens which the prophets foretold concerning Christ, did not understand Scripture until Christ opened up the meaning so that they understood Scripture. (p. 218)

At this point when will you stop throwing prophets, baptists, and apostles at us? No one doubts their Spirit, and their authority is sacrosanct. Because they had the Spirit teaching them from within, they explained what is obscure in the writings of the prophets. We were talking about your spirit and that of your followers, who profess that there is nothing in Holy Scripture which is obscure to you as long as you know grammar, and we demanded that you establish the credibility of this certainty, which you still fail to do, try as you may. (p. 219)

. . . when the Lord added ‘for those places speak of me,’ [John 5:39] he added a good deal of light, pointing out the aim of the prophecy. Just so in Acts, when Paul had taught and admonished them, they compared the scriptural passages with what had been carried out and what had been propounded to them; and there was much they would not have understood if the apostle had not supplied this additional light. Therefore I am not making the passages obscure, but rather God himself wanted there to be some obscurity in them, but in such a way that there would be enough light for the eternal salvation of everyone if he used his eyes and grace was there to help. No one denies that there is truth as clear as crystal in Holy Scripture, but sometimes it is wrapped and covered up by figures and enigmas so that it needs scrutiny and an interpreter, either because God wanted in this way to arouse us from dullness and also to set us to work, as Augustine says, or because truth is more pleasant and affects us more deeply when it has been dug out and shines forth to us through the cover of darkness than if it had been exposed for anyone at all to see . . . (pp. 219-220)

. . . if, as you teach, nothing is needed for Holy Scripture except grammar, what need is there to hear a preacher expound and interpret it? It would be enough to read out a prophet or the gospel to the common people who do not have the sacred books without explaining anything at all, unless there might perhaps be some underlying difficulty about the words. (pp. 221-222)

If Holy Scripture is perfectly clear in all respects, where does this darkness among you come from, whence arise such fights to the death about the meaning of Holy Scripture? You prove from the mysteries of Scripture that the body of the Lord is in the Eucharist physically; from the same Scripture Zwingli, Oecolampadius, and Capito teach that it is only signified. (p. 222)

You say this as if I said that all Scripture is obscure and ambiguous, though I confess that it contains a treasure of eternal and most certain truth, but in some places the treasure is concealed and not open to just anybody, no matter who. The sun is not dark if it does not appear when it is covered by clouds or if a dim-sighted person gropes about in full daylight . . . I was dealing with intricate questions which arise from Holy Scripture as it is interpreted first in one way and then in another. Here was the place you should have brought forth that most certain light of yours by which you convict the whole church of blindness. For, as to that quibble of yours that this light is always concealed in that church which is hidden and not thought to be the church, even if I granted you this (which you cannot prove), it is more probable that the holiest and also most learned men belonged to that hidden church than that you and your few adherents do. (p. 223)

The same thing also happens to you followers: Bugenhagen and Oecolampadius speak about some places with doubts and hesitation, and in the end even Philippus [Melanchthon] does, for whom there is no end to your praises. Everything which you thundered with such vehemence and lavishness against those who think there is anything obscure in Scripture recoils on the heads of your followers and even on your own. Finally, you yourself confess that obscurity occurs in the mysteries of Scripture because of ignorance about words, and you will add, I think, because of corruptions in the manuscripts, figures of speech, and places which conflict with one another. Once you admit this, all the disadvantages return which you attributed to obscurity. For it does not matter where the obscurity comes from as long as some is there. Such obscurity you certainly cannot deny. But if you eliminate all faith in those who are at a loss anywhere, you yourself are at a loss and so are your adherents, in whom you wish us to have wholehearted faith. (pp. 225-226)

And he [Paul] says there: ‘We know partially and we prophesy partially,’ and a little further on ‘Now I know partially, but then I shall know as I am known.’ [1 Cor 13:9,12] By prophecy Paul means the interpretation of the mysteries of Scripture; why would he profess that it is imperfect if there is nothing which is not perfectly clear? And if Paul here acknowledges imperfection, where are those who now boast of omniscience? (p. 234)

But you will say that Zwingli and Oecolampadius lost the Spirit after they started writing against you. (p. 235)

But if you attribute a total understanding of the Holy Scripture to the Holy Spirit, why do you make an exception only for the ignorance of grammar? In a matter of such importance will the Spirit allow grammar to stand in the way of man’s salvation? Since he did not hesitate to impart such riches of eternal wisdom, will he hesitate to impart grammar and common sense? (p. 239)

If you contend that there is no obscurity whatever in Holy Scripture, do not take up the matter with me but with all the orthodox Fathers, of whom there is none who does not preach the same thing as I do. (p. 242)

For which of them [the Church Fathers], in explaining the mysteries in these volumes, does not complain about the obscurity of Scripture? Not because they blame Scripture, as you falsely charge, but because they deplore the dullness of the human mind, not because they despair but because they implore grace from him who alone closes and opens to whomever he wishes, when he wishes, and as much as he wishes. (pp. 244-245)

But I am resolved in matters of faith not to give any weight to private feelings. (p. 247)

Both the Spirit and common sense and the clarity of Holy Scripture are claimed by both sides. . . . Grant that Scripture is perfectly clear: what will we unlearned people do when we see both sides contending with equal assertiveness that they have the Spirit who reveals mysteries and that they find Scripture absolutely clear? Grant that it is obscure in some places: what will we do when each side accuses the other of blindness? However these things may be, we are certainly left wavering in doubt, and in the meantime you neither acquit your faith by fulfilling your promise nor set us free by removing our doubt. (p. 254)