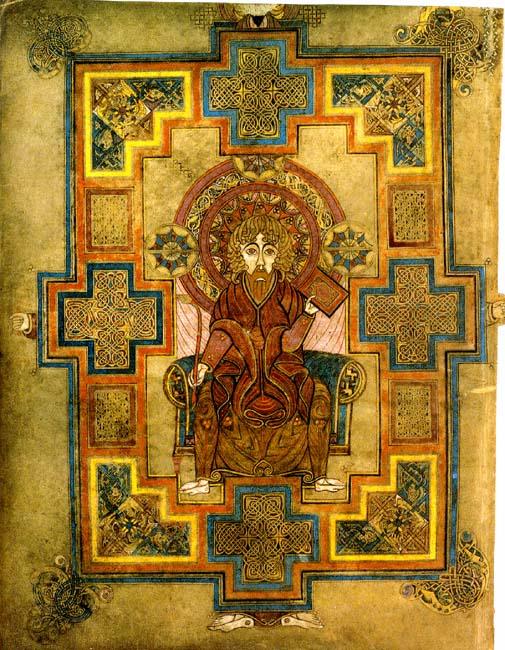

Book of Kells (Ireland: c. 800), Folio 291v, Portrait of St. John [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(1996; from my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism)

***

In order for Protestants to exercise the principles of sola Scriptura they first have to accept the antecedent premise of what books constitute Scripture — in particular, the New Testament books. This is not as simple as it may seem at first, accustomed as we are to accepting without question the New Testament as we have it today.

Although indeed there was, roughly speaking, a broad consensus in the early Church as to what books were scriptural, there still existed enough divergence of opinion to reasonably cast doubt on the Protestant concepts of the Bible’s self-authenticating nature, and the self-interpreting maxim of perspicuity.

The following overview of the history of acceptance of biblical books (and also non-biblical ones as Scripture) will help the reader to avoid over-generalizing or over-simplifying the complicated historical process by which we obtained our present Bible.

A Visual Diagram of the History of the New Testament Canon

Explanation of Symbols:

* Book accepted (or quoted)

? Book personally disputed or mentioned as disputed

x Book rejected, unknown, or not cited

New Testament Period (c. 35-90)

In this period there is little formal sense of a canon of Scripture

*****

Apostolic Fathers (90-160)

Summary: The New Testament is still not clearly distinguished qualitatively from other Christian writings

Gospels Generally accepted by 130

Justin Martyr’s “Gospels” contain apocryphal material

Polycarp first uses all four Gospels now in Scripture

Acts Scarcely known or quoted

Pauline Corpus Generally accepted by 130, yet quotations are rarely introduced as scriptural

Philippians, 1 Timothy: x Justin Martyr

2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon: x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

Hebrews Not considered canonical

? Clement of Rome

x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

James Not considered canonical; not even quoted

x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

1 Peter Not considered canonical

2 Peter Not considered canonical, nor cited

1, 2, 3 John Not considered canonical

x Justin Martyr

1 John ? Polycarp / 3 John x Polycarp

Jude Not considered canonical

x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

Revelation Not canonical

x Polycarp

*****

Irenaeus to Origen (160-250)

Summary: Awareness of a canon begins towards the end of the 2nd century

Tertullian and Clement of Alexandria first use phrase New Testament

Gospels Accepted

Acts Gradually accepted

Pauline Corpus Accepted with some exceptions:

2 Timothy: x Clement of Alexandria

Philemon: x Irenaeus, Origen, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

Hebrews Not canonical before the 4th century in the West.

? Origen

* First accepted by Clement of Alexandria

James Not canonical

? First mentioned by Origen

x Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

1 Peter Gradual acceptance

* First accepted by Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria

2 Peter Not canonical

? First mentioned by Origen

x Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

1 John Gradual acceptance

* First accepted by Irenaeus

x Origen

2 John Not canonical

? Origen

x Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

3 John Not canonical

? Origen

x Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

Jude Gradual acceptance

* Clement of Alexandria

x Origen

Revelation Gradual acceptance

* First accepted by Clement of Alexandria

x Barococcio Canon, c.206

Epistle of Barnabas * Clement of Alexandria, Origen

Shepherd of Hermas * Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Clement of Alexandria

The Didache * Clement of Alexandria, Origen

The Apocalypse of Peter * Clement of Alexandria

The Acts of Paul * Origen

* Appears in Greek, Latin (5), Syriac, Armenian, & Arabic translations

Gospel of Hebrews * Clement of Alexandria

*****

Muratorian Canon (c. 190)

Excludes Hebrews, James, 1 Peter, 2 Peter

*****

Origen to Nicaea (250-325)

Summary: The Catholic epistles and Revelation are still being disputed

Gospels, Acts, Pauline Corpus Accepted

Hebrews * Accepted in the East

x, ? Still disputed in the West

James x, ? Still disputed in the East

x Not accepted in the West

1 Peter Fairly well accepted

2 Peter Still disputed

1 John Fairly well accepted

2, 3 John, Jude Still disputed

Revelation Disputed, especially in the East

x Dionysius

*****

Council of Nicaea (325)

Questions canonicity of James, 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, and Jude

*****

From 325 to the Council of Carthage (397)

Summary: Athanasius first lists our present 27 New Testament books as such in 367. Disputes still persist concerning several books, almost right up until 397, when the canon is authoritatively closed

Gospels, Acts, Pauline Corpus, 1 Peter, 1 John Accepted

Hebrews Eventually accepted in the West

James Slow acceptance

Not even quoted in the West until around 350!

2 Peter Eventually accepted

2, 3 John, Jude Eventually accepted

Revelation Eventually accepted

x Cyril of Jerusalem, John Chrysostom, Gregory Nazianz

Epistle of Barnabas * Codex Sinaiticus – late 4th century

Shepherd of Hermas * Codex Sinaiticus – late 4th century

Used as a textbook for catechumens according to Athanasius

1 Clement, 2 Clement * Codex Alexandrinus – early 5th century (!)

Protestants do, of course, accept the traditional canon of the New Testament (albeit somewhat inconsistently and with partial reluctance — Luther questioned the full canonicity of James, Revelation and other books). By doing so, they necessarily acknowledged the authority of the Catholic Church. If they had not, it is likely that Protestantism would have gone the way of all the old heresies of the first millennium of the Church Age — degenerating into insignificant, bizarre cults and disappearing into the putrid backwaters of history.

2) F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2nd edition, 1983, 232, 300, 309-10, 626, 641, 724, 1049, 1069.

3) Norman L. Geisler & William E. Nix, From God to Us: How We Got Our Bible, Chicago: Moody Press, 1974, 109-12, 117-125.