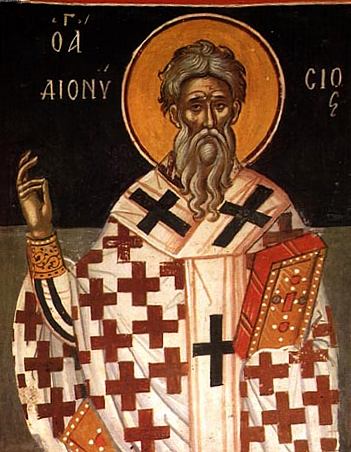

Pope St. Dionysius of Alexandria (anonymous icon) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

(8-1-03)

***

For preliminaries concerning my methodology and the burden of proof for showing if a Church Father believed in sola Scriptura, see my paper, Church Fathers & Sola Scriptura. Dionysius’ words will be in blue. Evangelical Protestant / Anti-Catholic apologist Jason Engwer’s words will be in green.

***

St. Dionysius of Alexandria was pope from 247 or 248 until his death in 264 or 265.

Jason Engwer cites the following as alleged proof of belief in sola Scriptura:

Nor did we evade objections, but we endeavored as far as possible to hold to and confirm the things which lay before us, and if the reason given satisfied us, we were not ashamed to change our opinions and agree with others; but on the contrary, conscientiously and sincerely, and with hearts laid open before God, we accepted whatever was established by the proofs and teachings of the Holy Scriptures. – Dionysius of Alexandria (cited in the church history of Eusebius, 7:24)

This is not proof that Dionysius held to sola Scriptura, in and of itself. Catholics, too, accept “whatever was established by the proofs and teachings of the Holy Scriptures.” That doesn’t mean that Scripture is isolated by itself or self-interpreting, nor that Dionysius neglected the authority of the Church and Tradition. We must look elsewhere to find his opinions on those so that we can determine if he truly accepted sola Scriptura or not. Catholic apologist and patristics expert Joe Gallegos wrote, in responding to anti-Catholic apologist William Webster:

Mr. Webster in an essay titled “Sola Scriptura and the Early Church” has attempted to transform the early Church Fathers into proponents of sola Scriptura. In my contribution in Not by Scripture Alone (Santa Barbara:Queenship,1997) chapter 8 and appendix I delineate three approaches used by Protestant apologists in defending sola Scriptura in patristic thought. William Webster has chosen the third approach; equating sola Scriptura with the material sufficiency of Scripture. Mr. Webster writes:

The Reformation was responsible for restoring to the Church the principle of sola Scriptura, a principle which had been operative within the Church from the very beginning of the post apostolic age. Initially the apostles taught orally but with the close of the apostolic age all special revelation that God wanted preserved for man was codified in the written Scriptures. Sola Scriptura is the teaching and belief that there is only one special revelation from God that man possesses today, the written Scriptures or the Bible, and that consequently the Scriptures are materially sufficient and are by their very nature as being inspired by God the ultimate authority for the Church.

Two points are to be noted here. First, Mr. Webster equates sola Scriptura with the material sufficiency of Scripture. Second, according to Mr. Webster, the Reformers were responsible for restoring this narrow understanding of sola Scriptura. Sola Scriptura consists of a material and a formal element. First, sola Scriptura affirms that all doctrines of the Christian faith are contained within the corpus of the Old and New Testaments. Hence, Scripture is materially sufficient. Secondly, Scripture requires no other coordinate authority such as a teaching Church or Tradition in order to determine its meaning. Sola Scriptura affirms the formal sufficiency of Scripture. Catholics are allowed to affirm Scripture’s material sufficiency, therefore Mr. Webster’s case directed at proving the Fathers belief in Scripture’s material sufficiency is completely off target. In order for Mr. Webster to make his case for sola Scriptura he must prove that the Fathers affirmed the formal sufficiency of Scripture. The Fathers affirmed both the material sufficiency and formal insufficiency of Scripture.A bit more surprising is that Mr. Webster has us believe that the Reformers equated sola Scriptura with material sufficiency. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Calvin writes:

But a more pernicious error widely prevails that Scripture has only so much weight as is conceded to it by the consent of the church. As if the eternal and inviolable truth of God depended upon the decision of men! For they mock the Holy Spirit when they ask: Who can convince us that these writings came from God? Who can assure us that the Scripture has come down whole and intact even to our day?…Thus, the highest proof of Scripture derives in general form from the fact that God in person speaks in it…Let this point therefore stand: that those whom the Holy Spirit has inwardly taught truly rest upon Scripture, and that Scripture indeed is self-authenticated; hence, it is not right to subject it to proof and reasoning. And the certainty it deserves with us, it attains by the testimony of the Spirit. (Institutes of the Christian Religion, I: 7:1, 4-5)

Similarly Luther writes:

[T]he truth is that nobody who has not the Spirit of God sees a jot of what is in the Scriptures … [N]othing whatsoever is left obscure or ambiguous, but that all that is in the Scripture is through the Word brought forth in the clearest light and proclaimed to the whole world. (Bondage of the Will, 175)

. . . The Reformers’ position affirmed both the formal and material sufficiency of Scripture. Mr. Webster has misrepresented the faith of the Reformers by having us believe that they affirmed his narrow definition of sola Scriptura. The doctrine of sola Scriptura requires no other coordinate authority such as Tradition or a teaching Church in order to interpret all of its doctrines in an orthodox manner. In contrast, Mr. Webster narrows the definition of sola Scriptura to only mean material sufficiency. However, this caricature of sola Scriptura is innocuous since Catholics can affirm the material sufficiency of Scripture. Likewise, Mr. Webster’s use of the Fathers in support of material sufficiency is off target. Catholics agree that the Fathers affirmed the material sufficiency of Scripture. However, in the same breath, these very same Fathers affirmed the formal insufficiency of Scripture. I will provide passages from the very same Fathers that are cited by Mr. Webster that affirm the formal insufficiency of Scripture.(“The Fathers know best Not Mr. Webster!”)

We don’t have much writing from Dionysius of Alexandria. But we do have his opinion on the book of Revelation. Note Calvin’s opinion above: “Scripture indeed is self-authenticated; hence, it is not right to subject it to proof and reasoning.” And Luther’s: “in the Scriptures…nothing whatsoever is left obscure or ambiguous . . . ” Jason writes in a section in his same work, on St. John Chrysostom: “John Chrysostom said that each individual should read scripture and interpret it for himself,” and contrasted this with the Catholic position. If these notions are part and parcel of sola Scriptura, Dionysius does not agree with them, for in the same excerpt and source that Jason cites above, he gives his opinion on the book of Revelation:

Some of our predecessors rejected the book . . . But I myself would never dare to reject the book, of which many good Christians have a very high opinion, but realizing that my mental powers are inadequate to judge it properly, I take the view that the interpretation of the various sections is largely a mystery, something too wonderful for our comprehension. I do not understand it, but I suspect that some deeper meaning is concealed in the words; I do not measure and judge these things by my own reason, but put more reliance on faith, and so I have concluded that they are too high to be grasped by me. (cited in Eusebius, The History of the Church, 7:25, p. 309 in 1965 Penguin Books edition; translated by G. A. Williamson)

Dionysius calls the author or Revelation a “prophet” and “a holy and inspired writer” (ibid., 310). But the obscurity of interpretation of Revelation appears to be the reason why Martin Luther rejected its apostolicity, along with that of Hebrews, James, and Jude, although he does say they are “fine” books. In his Preface to Revelation, from 1522- – from the time period in which he was translating the Bible), Luther pontificates:

I miss more than one thing in this book, and this makes me hold it to be neither apostolic nor prophetic. . . . I think of it almost as I do of the Fourth Book of Esdras, and can nohow detect that the Holy Spirit produced it . . .It is just the same as if we had it not, and there are many far better books for us to keep.

. . . Finally, let everyone think of it as his own spirit gives him to think. My spirit cannot fit itself into this book. There is one sufficient reason for me not to think highly of it, – Christ is not taught or known in it; but to teach Christ is the thing which an apostle is bound, above all else, to do, as He says in Acts 1, ‘Ye shall be my witnesses.’ Therefore I stick to the books which give me Christ, clearly and purely.

(Works of Martin Luther, Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1932, copyrighted by the United Lutheran Church in America, vol. 6. 488-489, translated by C. M. Jacobs)

It is clear what is going on in Luther’s mind, I think. He presupposes that all of Scripture is perspicuous and self-interpreting. He then looks at Revelation and does not see this. Therefore, he concludes — based on his axiomatic, unproven presuppositions –, that the book is not apostolic, because he himself cannot figure it out and thus he has “sufficient reason” to question and reject it, based on his own purely subjective “spirit.” His argument starts with an unprovable axiom and ends in radical circularity and subjectivism. If Dionysius had had Luther’s mindset, he would have drawn the same conclusion about Revelation. But he did not. He accepted the book, precisely because he was relying not on sola Scriptura and its aspect of perspicuity, but on Church Tradition.

Referring back to his citation from Dionysius (at the top), Jason wrote:

If he meant to refer to scripture and an infallible interpretation of it from the church, why would he only mention scripture?

For the same reason that the Apostle Paul only mentions tradition in several passages, and not Scripture (e.g., 1 Cor 11:2; 1 Thess 2:13; 2 Thess 3:6; 1 Tim 3:15; 2 Tim 1:13-14; 2:2). Does that mean that he doesn’t accept Scripture as an authority? By the same token, mere mention of Scripture without tradition or the Church does not entail a conclusion that a writer rejects those necessary elements. How many times must I say this?

The dispute in question was over eschatology. If the dispute was settled by means of an infallible church’s interpretation of scripture, would Dave tell us what infallible pronouncements on eschatology existed at this time in church history, namely the middle of the third century? Dionysius thought scripture itself sufficient for “accepting” beliefs that were “established” by it.

It is materially sufficient.

He says nothing of a Roman Catholic magisterium interpreting scripture for us, nor does he even say that the dispute was settled by means of consulting fallible oral traditions.

Just as St. Paul often does not mention Scripture in one place or tradition in another. Who cares? It’s a non-issue.

[passed over off-topic comments about the precise content of the tradition]

Dave quotes Dionysius of Alexandria saying that he doesn’t understand some parts of the book of Revelation. But how does that refute what I argued with regard to his view of sola scriptura?

Dionysius wrote: “we accepted whatever was established by the proofs and teachings of the Holy Scriptures.” But if he himself cannot understand Revelation, then he needs an interpreter. True, he doesn’t say that this is authoritative Church interpretation or Tradition (as opposed to a good trained exegete or theologian), but that conclusion is as likely and plausible as your conclusion that he rejects Church and Tradition in the Catholic sense simply because he doesn’t mention them in one passage. This was my weakest case because not much material was available. In any event, your prooftext is not sufficient to prove that he held to sola Scriptura.

There are many parts of Revelation that I don’t understand. The sufficiency and the perspicuity of scripture are related, but different, issues. You don’t have to believe that every part of scripture is fully comprehended in order to believe in sola scriptura. John Calvin, Charles Spurgeon, and many other Protestant leaders through the centuries have acknowledged that there are passages of scripture they don’t fully comprehend, and that some parts of scripture are clearer than others.

I agree. This is also the Catholic view: that Scripture is largely clear, but not always.

*

Regarding the passages you cited from Paul, why should we expect him to mention scripture in a passage like 2 Thessalonians 3:6?

Indeed. Now you’re starting to get it. It’s not necessary to mention everything to do with authority every time one discusses it at all. Therefore, absence of reference to tradition and/or the Church and/or apostolic succession when mentioning Scripture in one passage doesn’t prove that the writer does not hold to any non-scriptural authority. You acknowledge this when tradition is mentioned, but not Scripture (as above), but not the other way around (which is inconsistent).

The whole point of the Pauline passages was to show that Paul certainly accepts the authority of Scripture, yet he often writes about tradition without mentioning it. Likewise, Fathers can write about Scripture in one place and this doesn’t prove that they do not hold to notions of tradition inconsistent with sola Scriptura, simply because they don’t mention it every time (as if that is necessary).

The term “tradition” would include all teachings, whether written or unwritten. I see no reason to conclude that scripture isn’t included in the passage.

Very good. And I see no reason to conclude that tradition isn’t included in your passages supposedly proving espousal of sola Scriptura, since, according to J. N. D. Kelly, the Fathers viewed the “content” of Scripture and the apostolic testimony (or tradition) as “virtually coincident” and “complementary authorities, media different in form but coincident in content.” Protestant historian Heiko Oberman speaks of “the early Church principle of the coinherence of Scripture and Tradition.” Etc., etc.

And there’s no reason to expect Paul to be exhaustive in a passage like 1 Corinthians 11:2 or 1 Thessalonians 2:13, where he’s referring to how the word of God historically came to these groups of Christians.

I agree. That’s not a problem in my position; only for your inconsistent application of your own peculiar brand of “logic.”

Dionysius, on the other hand, is discussing how a doctrinal dispute was settled. We wouldn’t expect him to only mention scripture if the dispute was settled by having an oral tradition or an infallible magisterium interpret scripture for them. The context of Paul’s comments and the context of Dionysius’ comments are different, so your comparison is absurd.

What is absurd is your reasoning here and seeming inability to understand the logical force of analogical arguments. My position is that the early Church held to a rule of faith quite unlike the later Protestant sola Scriptura position and essentially the same as the Catholic rule of faith today (as explained now countless times). This is established from abundant testimony and opinions of the expert (non-Catholic) historians in the field. Thus, a Father does not have to mention tradition every time he mentions Scripture (or vice versa) precisely because all of this is assumed to work together. One doesn’t often mention what is an axiom or premise.

So Dionysius doesn’t have to (i.e., it is not absolutely necessary for him to) talk about tradition in order to be perceived as accepting its authority. Likewise (here was where my analogy came in), the Apostle Paul doesn’t have to talk about Scripture every time he mentions tradition (as you agree). You accept that state of affairs for Paul but not for the Fathers. This is your inconsistency.

And to illustrate your inconsistency further, we shall make further biblical analogy, following up on your present immediate argument. You write:

We wouldn’t expect him to only mention scripture if the dispute was settled by having an oral tradition or an infallible magisterium interpret scripture for them.

Yet in a doctrinal dispute recorded in Holy Scripture itself, we find assembled bishops (James is considered by historians to have been the bishop of Jerusalem) and “apostles and elders,” in Jerusalem, in council (Acts 15:6), settling disputes, without mentioning Scripture. It is true that James does quote the Old Testament concerning the Gentiles coming into the fold of God’s People (15:16-18) and hence indirectly, with regard to the question of circumcision, but the main decision of the council (often called an “apostolic decree”) was given without any biblical rationale whatever:

. . . it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity . . .(15:29; cf. 15:20 — RSV)

Prior to the decision, Peter had also spoken about the Gentiles, but gave no Scriptural support (15:7-11). Obviously, then, this authoritative council (including Paul, Peter, and James) was radically unbiblical (excepting one mention of the Gentiles’ spiritual destiny, too broad to determine the specific questions at hand). When the time came to make its decision, the Bible wasn’t mentioned.

So, let’s paraphrase your words in order to illustrate the force of the analogy, and to turn your “logic” back onto you:

. . . the Jerusalem Council (including Paul, Peter, and James), on the other hand, is discussing how a doctrinal dispute was settled. We wouldn’t expect it to not mention scripture if the dispute was settled by having an oral tradition or an infallible magisterium interpret scripture.

Yet this is precisely what happened. There are plenty of passages about circumcision in the OT, but none of them were mentioned (at least not in the record we have of the proceedings). The council was precisely an “infallible magisterium.” It made a binding decision. “Binding and loosing” are biblical concepts as well, which had to do with the authority of ecclesiastical leaders (see: Mt 16:19, 18:17-18, Jn 20:23).

We see, e.g., Peter offering a fully authoritative interpretation of Scripture, a doctrinal decision and a disciplinary decree concerning members of the “House of Israel” (Acts 2:36) in his sermon at Pentecost (Acts 2:14-41). He does cite Scripture there, but of course this is no problem for my position, because I am taking the view that Scripture and Tradition don’t always have to be mentioned in every instance in order to be believed in, in the Catholic sense of binding authority, as (to borrow Kelly’s phrase) “complementary authorities, media different in form but coincident in content.”

I dealt with your present mindset in this discussion, in my first book, citing a similar passage from St. Paul:

Ephesians 4:11-15 And his gifts were that some should be apostle, some prophets, some evangelists, some pastors and teachers, for the equipment of the saints, for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ, until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ; so that we may no longer be children, tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness in deceitful wiles. Rather, speaking the truth in love, we are able to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ,

If the Greek artios (RSV, complete / KJV, perfect) proves the sole sufficiency of Scripture in 2 Timothy, then teleios (RSV, mature manhood / KJV, perfect) in Ephesians would likewise prove the sufficiency of pastors, teachers and so forth for the attainment of Christian perfection. Note that in Ephesians 4:11-15 the Christian believer is equipped, built up, brought into unity and mature manhood, knowledge of Jesus, the fulness of Christ, and even preserved from doctrinal confusion by means of the teaching function of the Church. This is a far stronger statement of the perfecting of the saints than 2 Timothy 3:16-17, yet it doesn’t even mention Scripture.Therefore, the Protestant interpretation of 2 Timothy 3:16-17 proves too much, since if all non-scriptural elements are excluded in 2 Timothy, then, by analogy, Scripture would logically have to be excluded in Ephesians. It is far more reasonable to synthesize the two passages in an inclusive, complementary fashion, by recognizing that the mere absence of one or more elements in one passage does not mean that they are nonexistent. Thus, the Church and Scripture are both equally necessary and important for teaching. This is precisely the Catholic view. Neither passage is intended in an exclusive sense.

(A Biblical Defense of Catholicism, Chapter One, pp. 15-16)

*****