The commonly heard polemic of Pope St. Gregory the Great (c. 540-604) allegedly eschewing the universal jurisdiction of the papacy (the famous “universal bishop” polemic) is easily disposed of. One must examine context and the rest of a person’s works and actions, if possible (just as with biblical exegesis). When that is done in this particular instance, Gregory’s meaning becomes quite clear, and alas, it is not at all what the contra-Catholic and “anti-papal” endeavor would have hoped.

Gregory the Great condemned the title “universal bishop” or “universal priest” in the sense of meaning that all other bishops are not really bishops, but mere agents of the one bishop, a concept that is blatantly contrary to Catholic teaching, which holds that all bishops are by divine institution true successors of the apostles. Thus, he states:

Be it known then to your Fraternity that John, formerly bishop of the city of Constantinople, against God, against the peace of the Church, to the contempt and injury of all priests, exceeded the bounds of modesty and of his own measure, and unlawfully usurped in synod the proud and pestiferous title of œcumenical, that is to say, universal. * . . . For if one, as he supposes, is universal bishop, it remains that you are not bishops. * * (Book 9, Letter 68)

I have however taken care to admonish earnestly the same my brother and fellow bishop that, if he desires to have peace and concord with all, he must refrain from the appellation of a foolish title. . . . I confidently say that whosoever calls himself, or desires to be called, Universal Priest, is in his elation the precursor of Antichrist, because he proudly puts himself above all others. Nor is it by dissimilar pride that he is led into error; for, as that perverse one wishes to appear as above all men, so whosoever this one is who covets being called sole priest, he extols himself above all other priests. (Book 7, Letter 33)

[W]hat will you say to Christ, who is the Head of the universal Church, in the scrutiny of the last judgment, having attempted to put all his members under yourself by the appellation of Universal? . . . not one of them [the apostles] has wished himself to be called universal. Now let your Holiness acknowledge to what extent you swell within yourself in desiring to be called by that name by which no one presumed to be called who was truly holy. (Book 5, Letter 18)

In the latter letter (5, 18), Gregory also writes:

. . . I, unworthy, succeeded to the government of the Church, . . .

For what are all your brethren, the bishops of the universal Church, but stars of heaven, whose life and discourse shine together amid the sins and errors of men, as if amid the shades of night? And when you desire to put yourself above them by this proud title, and to tread down their name in comparison with yours, what else do you say but I will ascend into heaven; I will exalt my throne above the stars of heaven? Are not all the bishops together clouds, who both rain in the words of preaching, and glitter in the light of good works?

. . . Peter, the first of the apostles, . . .

Was it not the case, as your Fraternity knows, that the prelates of this Apostolic See which by the providence of God I serve, had the honour offered them of being called universal by the venerable Council of Chalcedon. But yet not one of them has ever wished to be called by such a title, or seized upon this ill-advised name, lest if, in virtue of the rank of the pontificate, he took to himself the glory of singularity, he might seem to have denied it to all his brethren.

Gregory clearly upholds the universal authority and supremacy of the Roman bishop (the pope) in another of the letters cited above (9, 68); asterisks showing where in the text above these portions appear :

* When our predecessor Pelagius of blessed memory became aware of this, he annulled by a fully valid censure all the proceedings of that same synod, . . .

* * Furthermore, it has come to our knowledge that your Fraternity has been convened to Constantinople. And although our most pious Emperor allows nothing unlawful to be done there, yet, lest perverse men, taking occasion of your assembly, should seek opportunity of cajoling you in favouring this name of superstition, or should think of holding a synod about some other matter, with the view of introducing it therein by cunning contrivances,— though without the authority and consent of the Apostolic See nothing that might be passed would have any force, . . .

Protestant historian Philip Schaff makes short work of this “universal bishop” argument, which purports to prove something against the historic papacy:

On the other hand, it cannot be denied that Gregory, while he protested in the strongest terms against the assumption by the Eastern patriarchs of the antichristian and blasphemous title of universal bishop, claimed and exercised, as far as he had the opportunity and power, the authority and oversight over the whole church of Christ, even in the East. With respect to the church of Constantinople, he asks in one of his letters, who doubts that it is subject to the apostolic see? . . .

The real objection is to the pretension of a universal episcopate, not to the title. If we concede the former, the latter is perfectly legitimate. And such universal power had already been claimed by Roman pontiffs before Gregory, such as Leo I., Felix, Gelasius, Hormisdas, in language and acts more haughty and self-sufficient than his.

(History of the Christian Church, Volume IV: Mediaeval Christianity. A.D. 590-1073, 51. Gregory and the Universal Episcopate)

Pope St. Gregory the Great leaves little doubt as to his overall view of the sublime power and authority of the papacy and the primacy of the Roman Apostolic See:

Inasmuch as it is manifest that the Apostolic See is, by the ordering of God, set over all Churches, there is, among our manifold cares, special demand for our attention, when our decision is awaited with a view to the consecration of a bishop. . . . you are to cause him to be consecrated by his own bishops, as ancient usage requires, with the assent of our authority, and the help of the Lord; to the end that through the observance of such custom both the Apostolic See may retain the power belonging to it, and at the same time may not diminish the rights which it has conceded to others. (Book 3, Letter 30)

For as to what they say about the Church of Constantinople, who can doubt that it is subject to the Apostolic See, as both the most pious lord the emperor and our brother the bishop of that city continually acknowledge? (Book 9, Letter 12)

[Y]ou must still strictly order them to observe all things after the pattern of the Apostolic See. (Book 4, Letter 36)

[I]t was right that the Apostolic See should take heed, with the view of guarding in all respects the unity of the Universal Church in the minds of priests. (Book 4, Letter 2)

Further, I declare to your Charity that I am prepared, with the help of Almighty God, to prosecute this same cause with all my power and influence. And, should I see that in it the canons of the Apostolic See are not observed, Almighty God will give unto me what I may do against the contemners of the same. (Book 4, Letter 32)

This he did as knowing such reverence to be paid by the faithful to the Apostolic See that what had been settled by its decree no molestation of unlawful usurpation would thereafter shake. (Book 9, Letter 111)

Seeing, then, that you know the integrity of our faith from my plain utterance and profession, it is right that you should have no further scruple of doubt with respect to the Church of the blessed Peter, Prince of the apostles: but persist in the true faith, and make your life firm on the rock of the Church; that is on the confession of the blessed Peter, Prince of the apostles, lest all those tears of yours and all those good works should come to nothing, if they are found alien from the true faith. For as branches dry up without the virtue of the root, so works, to whatsoever degree they may seem good, are nothing, if they are disjoined from the solidity of the faith. (Book 4, Letter 38)

For to all who know the Gospel it is apparent that by the Lord’s voice the care of the whole Church was committed to the holy Apostle and Prince of all the Apostles, Peter. For to him it is said, Peter, do you love Me? Feed My sheep John 21:17. To him it is said, Behold Satan has desired to sift you as wheat; and I have prayed for you, Peter, that your faith fail not. And thou, when you are converted, strengthen your brethren Luke 22:31. To him it is said, You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build My Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give unto you the keys of the kingdom of heaven and whatsoever you shall bind an earth shall be bound also in heaven; and whatsoever you shall loose on earth shall be loosed also in heaven Matthew 16:18.

Lo, he received the keys of the heavenly kingdom, and power to bind and loose is given him, the care and principality of the whole Church is committed to him, and yet he is not called the universal apostle; while the most holy man, my fellow priest John, attempts to be called universal bishop. . . .

Do I in this matter, most pious lord, defend my own cause? Do I resent my own special wrong? Nay, the cause of Almighty God, the cause of the Universal Church. . . .

If then any one in that Church takes to himself that name, whereby he makes himself the head of all the good, it follows that the Universal Church falls from its standing (which God forbid), when he who is called Universal falls. But far from Christian hearts be that name of blasphemy, in which the honour of all priests is taken away, while it is madly arrogated to himself by one.

Certainly, in honour of Peter, Prince of the apostles, it was offered by the venerable synod of Chalcedon to the Roman pontiff. But none of them has ever consented to use this name of singularity, lest, by something being given peculiarly to one, priests in general should be deprived of the honour due to them. (Book 5, Letter 20)

But we, who, though unworthy, have undertaken the government of the Apostolic See in the stead of Peter the prince of the apostles, are compelled by the very office of our pontificate to resist the general enemy by all the efforts in our power. (Book 2, Letter 48)

For the more you fear the Creator of all, the more fully may you love the Church of him to whom it was said, You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it; and to whom it is said, To you I will give the keys of the kingdom of heaven; and whatsoever you shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatsoever you shall loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven . . . (Book 13, Letter 39)

The title “Universal Bishop” may also be used in the sense of “Bishop of Bishops”, and in this sense it was applied by Eastern Christians (i.e., Catholics — this is before the Schism) to Popes Hormisdas (514-523), Boniface II (530-532) and Agapetus (535-36), although the popes never used it themselves (ostensibly wishing to avoid the above interpretation) until the time of Leo IX (1049-54).

[information from the above paragraph was derived from: The Question Box, Bertrand Conway, New York: Paulist Press, 1929 edition, 158-159]

Lutheran historian Jaroslav Pelikan writes:

The churches of the Greek East, too, owed a special allegiance to Rome . . . One see after another had capitulated in this or that controversy with heresy. Constantinople had given rise to several heretics during the fourth and fifth centuries, notably Nestorius and Macedonius, and the other sees has also been known to stray from the true faith occasionally. but Rome had a special position. The bishop of Rome had the right by his own authority to annul the acts of a synod. In fact, when there was talk of a council to settle controversies, Gregory asserted the principle that ‘without the authority and the consent of the apostolic see, none of the matters transacted [by a council] have any binding force.’ (The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition [100-600], Univ. of Chicago Press, 1971, 354; cites Gregory’s Epistle 9.156)

See also the General Audience (4 June 2008) of Pope Benedict XVI, on Pope St. Gregory the Great and the papal encyclical Iucunda Sane / On Pope Gregory the Great, by Pope St. Pius X (12 March 1904).

* * * *

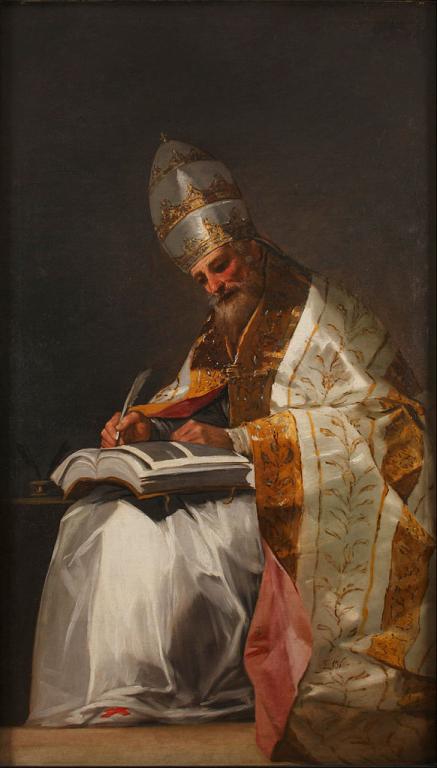

Photo credit: Saint Gregory the Great, Pope, by Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]