Part Two: Nature Mysticism, Romanticism, Bible Movies, and the “Great Depression” (1968-1977)

This is the ten-part story of my complete religious history, from nominal Methodism (1958-1967), to the occult and practical atheism (1968-1976), through evangelical Protestantism, counter-cult, pro-life, evangelistic, and apologetics work (1977-1990), and finally on to the fullness of the Catholic faith in 1991. It is found complete (75 pages) in my 2013 book, Catholic Converts and Conversion.

See All Ten Parts:

Part One: Nominal Methodism, Occult, and the Seeds of a Serious Christian Commitment (1958 – early 1970s)

Part Two: Nature Mysticism, Romanticism, Bible Movies, and the “Great Depression” (1968-1977)

Part Three: Evangelical “Born-Again” (?) Experience, More Lukewarmness, and Personal Revival (1977-1982)

Part Four: Apologetics, Abundant Evangelical Blessings, and Protestant Evangelistic Campus Ministry (1983-1989)

* * * * *

Nature Mysticism, Romanticism, Music, and the Revealed God

If I was anything at all, religiously speaking, during this “second” period of my life (1968-1977), I was a nature mystic. I relate to C. S. Lewis’ story in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, in many respects: the experiences of the painful, melancholy, yet “joyful” yearnings that he calls sehnsucht, the fascination with mythology and fantasy, as exemplified in music by Wagner, Northernness, the Middle Ages, knights, castles, Camelot, fairy-tales, Robin Hood, Celtic mythology, etc. This is an idealized, parabolic, analogical, poetic thought-picture and “world” (in retrospect very “medieval” and Catholic).

I instinctively sensed the God-behind-nature, never (by the grace of God and His restraining hand) wholly descending to paganism or pantheism (although I toyed with several brands of the occult). Lewis discovered to his surprise that romanticism was a bridge leading to Christianity. That was definitely true in my case as well.

Romanticism was and is very dear and special to me, and I think at bottom it is essentially Christian, whether consciously or not. What the true Romantic seeks can only be consummated within a Christian worldview and structure.

Music, too, tied into my romanticism and nature mysticism. When I first heard orchestral excerpts of Richard Wagner’s Ring of the Niebelungs in 1974, it was literally a religious, quintessentially romantic, mystical experience. Here was gorgeous, inspired music that immediately conjured up all these deep, mystical, other-worldly images that I found within myself from an early age.

Beethoven (my favorite composer before I discovered the marvel of Wagner) had that effect, too, in a lesser fashion, since his music was more abstract: not conjuring up images so much as the strivings and aspirations of man, dynamism, the will to overcome adversity (symbolized by his own ineffably tragic deafness), etc. (as many music commentators often note).

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in particular is nothing less than a testament to the human spirit, which is, of course, derived from God’s image, and one might say that it is almost a religious experience to hear it. An online acquaintance shared with me that she never felt God’s presence so undeniably as in certain points of Beethoven’s Ninth.

I also experienced very much the same feeling upon first hearing Gustav Mahler’s First Symphony (probably in 1975): a work likewise steeped in Germanic nature mysticism and romantic wonder, in both its ecstatic and terrifying elements (and I first heard the triumphalistic last movement on the radio, for those who are familiar with this work).

Music was already, by then (as it remains to this day), a major part of my life, and God used it to draw me to Him. I played trombone in the symphony band and symphony orchestra at Cass Technical High School in Detroit: a nationally renowned music program, majoring in avocational music.

I also took piano lessons, and by age 12, could play Chopin’s Minute Waltz; by age 16, the trombone solo in Mahler’s Third Symphony. I taught myself baritone, too, and, in 1980, blues harmonica and guitar. My first job was ushering at Detroit Symphony Orchestra concerts.

C. S. Lewis, in his autobiography (Surprised by Joy), recounted feelings and thought-processes (during his nominally Christian days, between the ages of thirteen and fifteen) very similar to mine at the same period of my life. This reinforces his contention that the underlying yearnings are well-nigh universal.

His descriptions of what he felt upon hearing Wagner’s music (especially the Ring) are uncannily like my own experiences. It conjured up images in his head of “heroic drama . . . ecstasy, astonishment” and displayed “elements which my religion ought to have contained . . . very like adoration.” Lewis ends his extraordinary recollections by observing that he came across “the false gods there to acquire some capacity for worship against the day when the true God should recall me to Himself.”

I read this work of Lewis several years after my own stunning, quasi-religious encounter with Wagner’s music. I had never come across anything that so incredibly described my own interior feelings, that I was not able to verbalize (or possibly not even conceptualize) at all until I read Lewis, writing about almost identical experiences and feelings of his own.

Here was the meeting of music and religion (what is sometimes called “imaginative – or romantic – theology”), just as I had already experienced the intersection of architecture and stained glass with vague religious feeling, years earlier in my young life. If God can’t reach us through the mind and theology, He has many other ways. In my case, knowing my interests, He drew me to Himself via art, music, and nature.

In my own vague, ethereal, only half-conscious Romanticism — before I was educated enough to be able to understand, let alone articulate, Christian doctrines and dogmas — I subconsciously sought out religious experiences or intimations that transported me into religious, mystical, supernatural, fantastic realms. Romantic orchestral music (above all, Wagner) served this “secondary” function for me.

Nature was another such medium. I found everything there symbolic and parabolic. The forest wilderness, for example, represented the “other,” the unattainable, the transcendent, the mythological fairy-tale environment. Various mythologies and quasi-historical “worlds” played into this as-yet undefined mysticism: knights, Robin Hood and William Tell, King Arthur, Greek mythology, the American Indians, pristine ancient Ireland and its elves, the Scottish Highlands and its legends and ghosts, the Alps, the Black Forest in Germany, etc.

I didn’t know how many other people possessed these feelings. Nor was I likely to inquire. But I was very happy to find out (some years later) that my wife Judy felt much the same way (she loves Wagner, too), as did C. S. Lewis.

At this time (1974-1976), I had no inkling of the fact that what has been called the “mythopoeic imagination” is deeply, profoundly Christian and substantially identical with the “medieval worldview.” Malcolm Muggeridge wrote about this symbolism in an article entitled “Nature is a Parable”:

Everything that happens to us or in connection with us, all the happenings in the world, great and small, the whole exterior phenomenon of nature and of life — all that amounts to God speaking to us, sending out messages in code, and faith is the key whereby we may decipher them. It sounds very simple, but it’s somehow difficult to convey exactly . . . Nature is speaking to us. It is a parable of life itself, a revelation of fearful symmetry . . .

(National Review, 24 December 1982, 1608)

The notion of nature being a parable (it is no coincidence that Jesus often utilized agricultural parables to illustrate principles of the kingdom of heaven) is also part and parcel of the incarnation and its extension of sacramentalism. For God became man (John 1:1-5,14-18) and in so doing raised matter and particularly human flesh to untold heights. Thus creation bespeaks not only God’s existence as Creator, but also His ineffable glory, as we know from God’s own revelation (Romans 1:19-20).

I was experiencing God and Christianity on some indescribable level, by means of nature, fantasy, myth, and music. Christianity is the fulfillment of all this longing. C. S. Lewis often makes the argument throughout his works that such intense, painfully powerful yearnings within us are grounded in the fact that we were made for heaven. The fleeting pangs of nostalgia, melancholy, vivid dreams, idealism, the Quest, paradise, (deja vu?), what is called sehnsucht, etc. that so infect us are thus explained as having an origin in ontological, spiritual, divinely ordained reality.

I submit that within all of us is an innate consciousness of immortality and a sense of “pre-existence” (as Wordsworth alludes to in his poetry): not in the monistic, eastern sense of reincarnation, but rather, in the idealistic Platonic sense of eternal existence in the omniscient mind of God, the First Cause, the Creator, in Whom “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

Perhaps also we retain a consciousness of the Garden of Eden and the pristine, luminescent, perfect, unfallen paradisal earth, which reappears in frustratingly short-lived instances of the painful Nostalgia (sehnsucht) that Lewis describes so wonderfully.

I strongly, passionately believe all this now, but back in the late sixties and early seventies (during roughly the ages of ten to twenty in my life), I was searching for the meaning behind my “mysticism” and ruminations. I still vividly recall the profound, quasi-religious experience of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and its incredible “light show” that represented a trip through eternity and space.

The scene still has the capacity of leaving me (and many others) dumbstruck with awe. There is something behind all of that, which gives it its challenging, “spiritual” quality. It was another religious experience brought on by the art of cinema and music, with philosophical and scientific aspects also added in. My inquisitive mysticism and curiosity were running wild. This was literally my “religion” in 1968, after the “dud” of my previous Methodist churchgoing experience. Hearing Wagner took it a step further six years later.

I believed in the spiritual, supernatural world, but I needed a doctrinal, rational basis upon which to discern truth from falsity, good from evil, edifying from destructive. All this is a fair indication, I think, that the drive for God and the transcendent is inherently within us, whether or not we understand the origin and goal of it. We are made in God’s image — funny that we should constantly try to remake God in our image.

My occultic leanings, mentioned above, were also similar to the pre-Christian experiences of C. S. Lewis. In his autobiography, he refers to a “desire for the preternatural, . . . passion for the Occult. . . . a spiritual lust; . . . making everything else in the world seem uninteresting while it lasts.”

As it turned out, God also saw to it that my morbid fascination for the unknown and the mysterious got channeled into an interest in Bible prophecy, shortly before, and for several years after my conversion. That allowed me to explore an area of “transcendent,” “unusual” happenings, all the while remaining within orthodox Christianity.

“The Great Depression” and Spiritual, Existential Crisis (1977)

It took the horrific experience of severe depression for six months at age 18 (in 1977) to get me to see that I couldn’t survive on my own. I was under this illusion that one could live without God, as if His existence makes very little difference at all in day-to-day life (what is called “practical atheism”: living as if God didn’t exist). I had gone along for ten years without going to church: a very secular life.

Like many people, I had a lot of pride and a self-delusion of self-sufficiency without God. He more or less had to knock me down and put me right on my back to wake me up to reality. The immediate causes were the pressures of late adolescence, not knowing what I was going to do with my life, and dating experiences that had ended up sadly.

When a person has such a large amount of stubbornness and stupidity, sometimes drastic action is necessary. God loves us enough to do whatever it takes to wake us up. He allows a person to suffer, with the ultimate goal of causing them to repent by hitting bottom and waking up (rather than being lost).

Going through serious, clinical depression is enough to scare the wits out of anyone, I think. I went from a very self-confident, “got it all together” person to someone who was in the deepest despair and anguish: unable to figure out why I was depressed or how in the world I would get out of the deep dark pit that I was in.

My self-image and seeming “happiness” was annihilated. I had never experienced anything like that before, and never since that time. Thus, in my mind, in retrospect, I think the larger purpose of it in God’s providence was to cause me to finally decide to yield up my self-will (and myself, period) to God.

God was using the circumstances to bring home to me the ultimate meaninglessness of my life: a vacuous and futile individualistic quest for happiness without purpose or relationship with God. I was brought, staggering, to the end of myself. It was a frightening existential crisis in which I had no choice but to cry out to God. In His tender mercy, He accepts even this “default” / last resort discipleship.

I’ve always interpreted what I call the terrifying “Great Depression” period of my life as God, in effect, saying, “okay, Dave. You want to live without Me? Do you truly want to see what it would be like to live a life of no hope and meaning; a world without God? Alright; I’ll let you do that.” And I saw what a truly Godless, nihilistic universe would be like and wanted no part of that whatsoever! I couldn’t play that game anymore.

In my case, obviously God knew (being omniscient) that I would soon cry out, so it was literally an act of mercy to give me totally over to my own corrupt desire of living a life of “practical atheism.” Many atheists can delude themselves and pretend as if a world without God still has meaning, but I was allowed the privilege of seeing what a consistent atheism leads and reduces to: black despair and meaninglessness.

God was quick to respond to my anguished cries. It was almost like I had no choice but to surrender to God and cease my rebellion against Him (somewhat like St. Paul in that respect). I had nowhere else to go. As I was coming out of the depression, having cried out to God, I felt that I literally experienced what King David did, as he expressed in Psalm 40:1-4:

I waited patiently for the LORD;

he inclined to me and heard my cry.

[2] He drew me up from the desolate pit,

out of the miry bog,

and set my feet upon a rock,

making my steps secure.

[3] He put a new song in my mouth,

a song of praise to our God.

Many will see and fear,

and put their trust in the LORD.

[4] Blessed is the man who makes

the LORD his trust,

who does not turn to the proud,

to those who go astray after false gods!

The Movie, Jesus of Nazareth and its Profound Impact on Me

It so happened that at Easter 1977 the superb Franco Zeffirelli film Jesus of Nazareth (still my favorite Christian movie) was on television. As I alluded to above, I had always enjoyed Bible movies, such as The Ten Commandments. They brought the biblical personalities to life.

The artistic element of drama communicated and powerfully brought home (at least to me) the vitality of Christianity in a unique and effective way. Dramatic films “make it real” and possess an emotional impact that doesn’t always come across in writing.

Jesus, as portrayed in this movie, made an extraordinary impression on me, and the timing couldn’t have been better. He seemed like the ultimate nonconformist, and that greatly appealed to me (God was again using elements that I could relate to, to draw me in). I marveled at the way He dealt with people, and how you could never expect what He would say or do; it was always something with unparalleled insight or impact.

It was a case of “the right thing at exactly the right time.” It remains my favorite Christian film. Beyond the excellence of the movie itself, as a piece of art, I think what moved me was being presented with a realistic portrayal of Jesus. I was dazzled by it. For the first time in my life I was confronted with what He was really like. The Person of Jesus was so immensely appealing that I could hardly not become His disciple after that experience.

I began to comprehend, with the help of my brother Gerry, the heart of the gospel for the first time: what the cross and Jesus’ passion meant, and some of the basic points of theology and soteriology (the theology of salvation) that I had never thought about before. I started to read the Bible seriously for the first time in my life (the Living Bible translation, which is the most informal paraphrase).

***

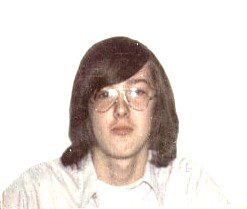

Photo: mug shot for a high school ID card: March 1976. I was 17, a senior in high school, and a relatively happy “practical atheist pagan”: with absolutely no clue that a year later I would experience the most shattering existential crisis of my life.