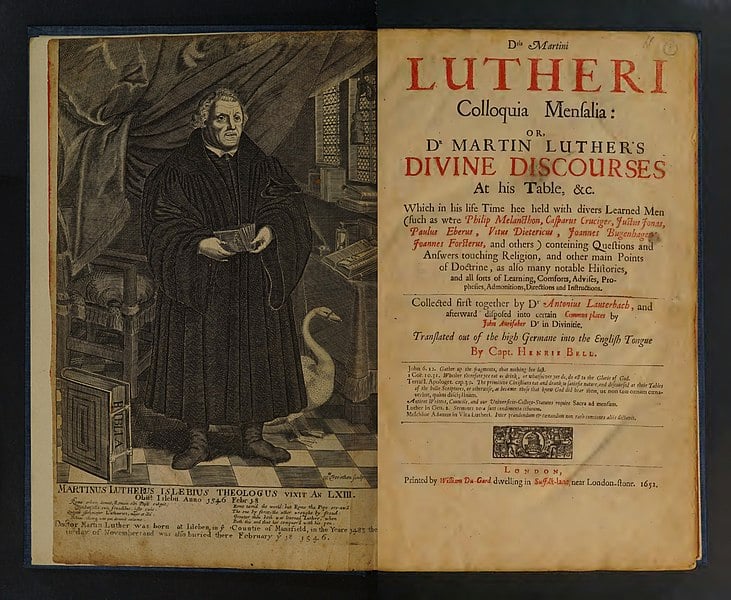

Photo credit: Frontispiece of the first English translation of Martin Luther’s Table Talk, edited by Captain Henry Bell and published in London in 1652 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Table Talk (in its many forms, of various levels of accuracy) purports to be transcriptions of utterances by Martin Luther, the founder of Protestantism. It’s not, technically, his own writing. All agree on that. I’d like to cite at some length, the Introduction to volume 54 of the 55-volume edition of Luther’s Works in English, dedicated to excerpts from Table Talk deemed to be the most reliable and accurate (as best can be determined by meticulous research).

The Introduction in Vol. 54 of Luther’s Works (Table Talk) — I have all 55 volumes in hardcover in my living room — , which runs from pp. ix-xxvi, was written by the Lutheran Theodore G. Tappert (1904-1973), who also edited and translated the entire volume. He was Schieren Professor of the History of Christianity at Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia and author, translator, or editor of many books, including the Book of Concord, which contains the binding Lutheran creeds and confessions. He was the key figure, along with Jaroslav Pelikan, in the editing and compilation of Luther’s Works. Here are excerpts from Tappert’s Introduction:

Conrad Cordatus claimed to have been the first man to record Luther’s conversation at table and asserted that Luther “never indicated by as much as a word that what I did displeased him.” . . . In fact, he [Luther] sometimes challenged the notetakers to record especially outrageous statements by saying, “Make a note of this!” “Write it down!” “Mark this well!” When his wife jestingly complained that those who were taking notes ought to pay for this additional instruction, Luther in effect defended those who were recording the conversation. (pp. x-xi)

Johann Georg Walch finally decided to incorporate the Table Talk in his edition, which was published in twenty-four volumes in Halle between 1739 and 1753. . . . Attempts were made to deny its genuineness, to claim that it was an unfriendly fabrication and forgery. (p. xi)

During the last decades of the nineteenth and the early decades of the twentieth century . . . manuscripts containing contemporary reports of Luther’s conversations were discovered in remote archives or rediscovered in libraries where they had long been overlooked. Some were edited and published, and these contained the notes taken by Anthony Lauterbach, Conrad Cordatus, John Schlaginhaufen, and John Matheius. Still other manuscripts were found to contain notes by Veit Dietrich and collections of sayings recorded by various other writers. All together, more than thirty manuscripts were found. . . .

There can be no doubt that these manuscripts take us much closer to the actual conversations at Luther’s table than the text offered by Aurifaber. It was the achievement especially of Ernst Kroker, whose painstaking editorial work made the six volumes of the Table Talk in the Weimar edition a model of literary and historical reconstruction, to demonstrate this. (pp. xv-xvi)

Questions have often been raised concerning the reliability of the reports of the Table Talk that have come down to us. . . . There is no doubt that the [newly discovered] manuscripts take us much closer to what was actually said that Aurifaber’s text does. But it is too much to claim that even the manuscripts provide us with verbatim reports. (p. xxii)

Although it cannot be said that available texts of the Table Talk reproduce word for word what was actually said at Luther’s table, it must nevertheless be added that the texts are reasonably trustworthy in reporting the subject matter and the directions which the conversation took. In other words, the Table Talk is less reliable than writings which we have from Luther’s own hand but not on this account to be dismissed as fiction. (pp. xxiii)

Preserved Smith (1880-1941): an American historian of the Protestant “Reformation”: whose doctoral dissertation at Columbia University (1907) was a critical study of the Table Talk, and who also wrote a biography of Luther, provided further details about these new Table Talk resources, alluded to by Dr. Tappert above:

The aim of the present translation is not, however, so much to correct the faults of previous ones as to bring new and important material to the attention of the English-speaking public. Until the present generation practically all that was known of the table talk was the edition of Aurifaber, and as an editor this person treated his material with extreme freedom — suppressing, omitting, expanding, and altering, to suit his own pious, rather than scholarly, purposes. The publication of the original records in recent years has for the first time offered a really good text and has also brought to light much that was unknown to Aurifaber. The first of these new sources to be published was Lauterbach’s ” Diary for 1538,” printed in 1872. Thirteen years afterwards Cordatus’s notes were given to the public, and three years later those of Schlaginhaufen. The records of Mathesius, Rabe and Heydenreich, with some of Lauterbach’s and Weller’s, were published by Lösche in 1892, and, from a much better manuscript, with additional notes of Besold and Plato, by Kroker in 1903. The important manuscripts of Dietrich and Medler did not issue from the press until 1912. As there are no more sources of importance as yet unpublished, the moment seems propitious for using this vast amount of new material. So voluminous is it that a selection only is practicable, but, though comparatively small, the present chrestomathy, it is hoped, will present to the reader of English most of the new material of first importance . . . (Conversations With Luther: Selections from Recently Published Sources of the Table Talk, translated and edited by Preserved Smith and Herbert Percival Gallinger, New York: The Pilgrim Press, 1915, Introduction, pp. xxv-xxvi)

Amateur blogger and Calvinist apologist and polemicist James Swan is more skeptical of Table Talk than the editors of Luther’s Works (“LW”) and the magisterial German edition (from which the former were drawn), published in Weimar in 1883, and Preserved Smith. Swan opined, for example:

It bears repeating that the Table Talk is not actually something Luther wrote. It’s a collection of second hand comments written down by Luther’s friends and students published after his death. It often falls on deaf ears when I point out to detractors that Luther didn’t write the Table Talk. Since the statements contained therein are purported to have been made by Luther, they should serve more as corroborating second-hand testimony to something Luther is certain to have written. The Table Talk, therefore, contains something Luther may have said, but not necessarily. (from his blog, Boors All, “Luther’s High Regard for John Calvin?,” 6-13-19)

Be careful with Luther’s Table Talk. The Table Talk is a collection of comments from Luther written down by Luther’s students and friends. It is not in actuality an official writing of Luther’s and should not serve as the basis for interpreting his theology. (“Luther: Christ was an Adulterer,” Boors All, 2-5-16)

But if the choice comes down to the conflicting opinions of Swan or the editors of the most authoritative editions of Luther’s writings in both German and English, who thought enough of the better versions of Table Talk to include them in their collections of what they call Luther’s “writings” — or the collections of Preserved Smith, then I choose the scholarly opinions of any of these men rather than the unscholarly amateur opinion of polemicist James Swan (nothing personal).

Photo credit: Frontispiece of the first English translation of Martin Luther’s Table Talk, edited by Captain Henry Bell and published in London in 1652 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Summary: I examine the historical trustworthiness of the various collections of Luther’s sayings during social meals, called “Table Talk” Should we regard (some) as Luther’s own words?