Why would there be a leader of the Church only for the lifetime of Peter? No other offices of leadership work that way.

Someone commented on my Facebook page:

Protestants always say that just because Peter was the leader, doesn’t mean that the leadership was passed down, because there is no mention in the Bible of Peter or his successors on how to transfer power.

Here’s my reply to that:

One of the apostles (Judas) was replaced with another (Matthias) and that is in the Bible. Therefore, why wouldn’t Peter also be replaced, as the manifest leader of the apostles (and according to Jesus, the leader of the Church)?

Secondly, why would there be a leader of the Church only for the lifetime of Peter? No one ever thinks like that about other offices of leadership. If a country is a monarchy, it has a succession of kings. We have a succession of Presidents in America. No one would think in 1789 that we should have George Washington to be our one and only President and then we would no longer need a President at all. Sports teams have successions of coaches. Corporations have a succession of CEOs, cities have mayors, schools have principals, etc. The offices or positions don’t simply end.

Yet when it comes to the papacy, people think like that. It’s absurd from common sense and analogy alone, but we also have biblical data that expressly contradicts it. Protestants even acknowledge other biblical Church offices of leadership that continue (pastors and deacons, and in some cases, bishops), yet they balk at accepting even a theoretical notion of a papal succession.

If Peter was the leader of the apostles and first head of the Church, then it only makes sense that he had successors. The burden on the Protestant, then, is to try to deny that Peter was the leader of the twelve and then of the new Christian Church. And that can’t really be done. If there is indeed such a thing as a papacy, then biblically speaking (and from analogy and common sense), there is a papal succession as well.

***

[further discussion from the original combox]

Dustin Buck Lattimore [Protestant] I’m not saying there is NO argument for a Petrine papal succession. I just don’t see it in Scripture, and the particular argument Dave offered is unconvincing to the non-convinced, or at least to this one.

Analogical arguments and arguments from deduction are usually rejected (or at least poorly understood) by Protestants, because they have this unbiblical notion that everything Christian believe must be absolutely explicit in the Bible. I’ve made at least two other arguments for papal succession (one / two).

I’m aware of your other arguments, and am not engaging with them here.

I’m merely asserting that the “argument from Matthias” is not a “simple straightforward biblical argument for papal succession”

And I’m legitimately curious about my original question: why are there not twelve successors to the apostles?

I would say it is indeed straightforward, but it’s also an analogical argument, incorporating common sense. Protestants usually only dimly understand analogical arguments. They think they are either exceedingly weak or irrelevant altogether.

There aren’t twelve successors because the disciples represent the collective leadership of the Church, whereas Peter is the preeminent leader. Therefore, the disciples have been succeeded by the collective of bishops, as needed, as the Church expanded.

Thus, Peter is given the power to bind and loose individually, singularly, by name, whereas the others receive it as a group. Every priest has this power, and so they are also descended from the disciples as a group or collective, via succession and ordination.

While I don’t think “finding an argument weak or irrelevant” = “dimly understanding an argument” is a fair assessment, I take your point.

As to your second point, I still find it pretty thin, but I won’t press the point.

Is your point that the example of Matthias illustrates the principle of apostolic succession?

(You know how you say a word so much it loses its meaning? I think I just did that with the word “point”)

Yes. And then by analogy I went on to argue that if Judas was succeeded, then why not also Peter, who was the leader? It makes no sense whatever to think that he was not.

If I concede that point, then it also makes no sense whatsoever to think the other eleven were not also directly succeeded. Why doesn’t the principle of succession also apply literally to the other eleven?

Again, they don’t have to be succeeded individually, but generally, as a collective. They were at first (Judas —> Matthias), but then it quickly became generalized as the Church expanded, and lost the direct relationship to the other disciples.

But there can still be instances where it is a more direct line. For example, the Orthodox regard the Patriarch of Antioch as the successor of Peter, who also preached there and was arguably a bishop while there.

Apostolic succession begins from the disciples and apostles.

Protestant historian J. N. D. Kelly wrote:

[T]he identity of the oral tradition with the original revelation is guaranteed by the unbroken succession of bishops in the great sees going back lineally to the apostles. . . . [A]n additional safeguard is supplied by the Holy Spirit, for the message committed was to the Church, and the Church is the home of the Spirit. Indeed, the Church’s bishops are . . . Spirit-endowed men who have been vouchsafed ‘an infallible charism of truth’. (Early Christian Doctrines, 37)

Some quotes from Cardinal Newman, from his Anglican period:

The doctrine in dispute is this; that Christ founded a visible Church as an ordinance for ever, and endowed it once for all with spiritual privileges, and set His Apostles over it, as the first in a line of ministers and rulers, like themselves except in their miraculous gifts, and to be continued from them by successive ordination; in consequence, that to adhere to this Church thus distinguished, is among the ordinary duties of a Christian, and is the means of his appropriating the Gospel blessings with an evidence of his doing so not attainable elsewhere. (Tracts for the Times #74, 1836)

A body of doctrine had been delivered by the Apostles to their first successors, and by them in turn to the next generation, and then to the next, as we have said above. “The things that thou hast heard from me through many witnesses,” says St. Paul to Timothy, “the same commit thou to faithful men, who shall be able to teach others also.” This body of truth was in consequence called the “depositum,” as being a substantive teaching, not a mere accidental deduction from Scripture. Thus St. Paul says to his disciple and successor Timothy, “Keep the deposit,” “hold fast the form of sound words,” “guard the noble deposit.” This important principle is forcibly insisted on by Irenæus and Tertullian before the Nicene era, and by Vincent after it. (“Apostolical Tradition,” British Critic, Vol. 19, July 1836)

. . . a person who denies the Apostolical Succession of the Ministry, because it is not clearly taught in Scripture, ought, I conceive, if consistent, to deny the divinity of the Holy Ghost, which is nowhere literally stated in Scripture. (Tracts for the Times #85, Sep. 1838)

Deacon Steven D. Greydanus Two other arguments worth noting:

1. The image of the “keys of the kingdom” in Matthew 16:19 alludes to Isaiah 22:22, where “the keys of the house of David” are a mark of the office of chief steward of the Davidic king. The passage refers to one chief steward succeeding another. This is not a prophetic archetype — it’s not like Shebna prefigures Peter and Eliakim his successor — but Jesus, the true Son of David, clearly likens Peter’s role to that of the Davidic king’s chief steward, and cites a passage involving succession to do it.

2. Cardinal Ratzinger, writing in “The Primacy of Peter and the Unity of the Church” (Called to Communion), makes an interesting argument based on the principles of historical criticism, notably the principle that the choice of materials preserved in scriptural texts tells us something about the times and the community in which the text was written as well as whatever it may tell us about the past.

In other words, the fact that Matthew’s Gospel — generally thought to be written post A.D. 75, after Peter’s death — included so much Petrine material, notably including Peter’s confession, Jesus surnaming him “rock” and declaring that he would build the Church on Peter, and giving him the keys of the kingdom, tells us something about Matthew’s community circa A.D. 75–80, not just about Jesus and Peter decades earlier.

According to this argument, the inclusion of this material reveals that Peter’s special role wasn’t just a historical fact about the founding of the Church; it was of ongoing significance to Matthew’s community after Peter’s death. Peter’s special role was in some way a living reality in the post-Petrine church. Petrine succession explains this in a way that is hard to do otherwise.

Very excellent. Thanks. I was thinking of delving into the chief steward aspect, but you saved me the trouble. There was succession there, and it’s another relevant scriptural analogy, that Jesus Himself drew in Matthew 16.

Jesus created a college of Apostles with one head, Peter. Only Peter has a special ministry in the college of the Apostles, so successors to the other apostles aren’t successors to a particular apostolic ministry in the same way that Peter’s successors are. That’s why there doesn’t have to be 12 — because there is no bishop who is specifically a successor to Andrew or James or John. Other bishops are successors to the Apostles collectively; only Peter has a successor to his own ministry.

That said, this point does put the argument from Matthias succeeding to Judas in some perspective. Matthias isn’t a successor to Judas in the same way that later bishops are successors to the Apostles; he’s really a *replacement* for Judas in the original college of the Twelve. The Apostles are, in a sense, Founding Fathers; in that capacity their role is unique, and Matthias is one of them. It’s those who exercise apostolic ministry after the apostles who are really “successors” in the relevant sense.

***

(originally 4-28-17)

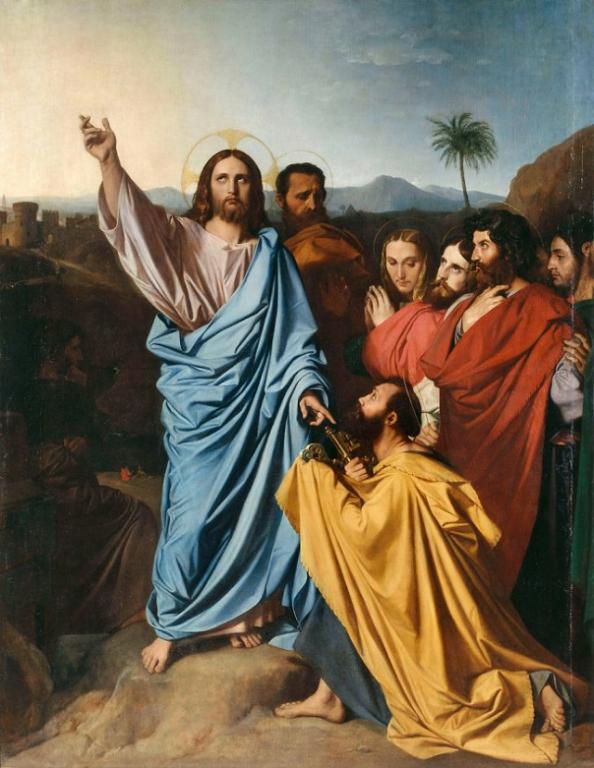

Photo credit: Jesus Returning the Keys to St. Peter (1820), by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***