Did St. Athanasius (c. 296-373) believe in sola Scriptura? Hardly. Let us look at some of his statements:

*****

But, beyond these sayings, let us look at the very tradition, teaching, and faith of the Catholic Church from the beginning, which the Lord gave, the Apostles preached and the Fathers kept. (To Serapion 1:28)

But after him and with him are all inventors of unlawful heresies, who indeed refer to the Scriptures, but do not hold such opinions as the saints have handed down, and receiving them as the traditions of men, err, because they do not rightly know them nor their power. (Festal Letter 2:6)

We may see easily, if we now consider the scope of that faith which we Christians hold, and using it as a rule, apply ourselves, as the Apostle teaches, to the reading of inspired Scripture. For Christ’s enemies, being ignorant of this scope, have wandered from the way of truth, and have stumbled on a stone of stumbling, thinking otherwise than they should think. (Discourse Against the Arians 3:28)

See, we are proving that this view has been transmitted from father to father; but ye, O modern Jews and disciples of Caiaphas, how many fathers can ye assign to your phrases? Not one of the understanding and wise; for all abhor you, but the devil alone; none but he is your father in this apostasy, who both in the beginning sowed you with the seed of this irreligion, and now persuades you to slander the Ecumenical Council, for committing to writing, not your doctrines, but that which from the beginning those who were eye-witnesses and ministers of the Word have handed down to us . For the faith which the Council has confessed in writing, that is the faith of the Catholic Church; to assert this, the blessed Fathers so expressed themselves while condemning the Arian heresy; and this is a chief reason why these apply themselves to calumniate the Council. For it is not the terms which trouble them , but that those terms prove them to be heretics, and presumptuous beyond other heresies. (Defense of the Nicene Definition, 27; A.D. 355; in NPNF2, IV:168-169)

But the sectaries,who have fallen away from the teaching of the Church, and made shipwreck concerning their Faith . . . (Contra Gentes, 6; A.D. 318, in NPNF2, XIV:7)

For, what our Fathers have delivered, this is truly doctrine; and this is truly the token of doctors, to confess the same thing with each other, and to vary neither from themselves nor from their fathers; whereas they who have not this character are to be called not true doctors but evil. (De Decretis 4; A.D. 351, in NPNF2,IV:153)

Had Christ’s enemies thus dwelt on these thoughts, and recognised the ecclesiastical scope as an anchor for the faith, they would not have made shipwreck of the faith, nor been so shameless as to resist those who would fain recover them from their fall, and to deem those as enemies who are admonishing them to be religious. (Orationes contra Arianos III:58; A.D. 362, in NPNF2, IV:425)

[The Fathers at Nicea]…but concerning matters of faith, they did not write: ‘It was decided,’ but ‘Thus the Catholic Church believes.’ And thereupon they confessed how they believed. This they did in order to show that their judgement was not of more recent origin, but was in fact Apostolic times; and that what they wrote was no discovery of their own, but is simply that which was taught by the apostles. (De Synodis 5; A.D. 362,in NPNF2,IV:453)

The blessed Apostle approves of the Corinthians because, he says, ‘ye remember me in all things, and keep the traditions as I delivered them to you’ (1 Cor. xi. 2); but they, as entertaining such views of their predecessors, will have the daring to say just the reverse to their flocks: ‘We praise you not for remembering your fathers, but rather we make much of you, when you hold not their traditions.’ (De Synodis 14; A.D. 362, in NPNF2, IV:453)

But the word of the Lord which came through the ecumenical Synod at Nicea, abides forever. (Ad Afros 2; A.D. 372, in NPNF2, IV:489)

Remaining on the foundation of the Apostles, and holding fast the traditions of the Fathers, pray that now at length all strife and rivalry may cease, and the futile questions of the heretics may be condemned, and all logomachy; and the guilty and murderous heresy of the Arians may disappear, and the truth may shine again in the hearts of all, so that all every where may ‘say the same thing'(1 Cor. i. 10), and think the same thing, and that, no Arian contumelies remaining, it may be said and confessed in every Church, ‘One Lord, one faith, one baptism’ (Eph. iv. 5), in Christ Jesus our Lord, through whom to the Father be the glory and the strength, unto ages of ages. Amen. (De Synodis 54; A.D. 362, in NPNF2, IV:453)

Such are the machinations of these men against the truth: but their designs are manifest to all the world, though they attempt in ten thousand ways, like eels, to elude the grasp, and to escape detection as enemies of Christ. Wherefore I beseech you, let no one among you be deceived, no one seduced by them; rather, considering that a sort of judaical impiety is invading the Christian faith, be ye all zealous for the Lord; hold fast, every one, the faith we have received from the Fathers, which they who assembled at Nicaea recorded in writing, and endure not those who endeavour to innovate thereon.

And however they may write phrases out of the Scripture, endure not their writings; however they may speak the language of the orthodox, yet attend not to what they say; for they speak not with an upright mind, but putting on such language like sheeps’ clothing, in their hearts they think with Arius, after the manner of the devil, who is the author of all heresies. For he too made use of the words of Scripture, but was put to silence by our Saviour. For if he had indeed meant them as he used them, he would not have fallen from heaven; but now having fallen through his pride, he artfully dissembles in his speech, and oftentimes maliciously endeavours to lead men astray by the subtleties and sophistries of the Gentiles.

Had these expositions of theirs proceeded from the orthodox, from such as the great Confessor Hosius, and Maximinus of Gaul, or his successor, or from such as Philogonius and Eustathius, Bishops of the East, or Julius and Liberius of Rome, or Cyriacus of Moesia, or Pistus and Aristaeus of Greece, or Silvester and Protogenes of Dacia, or Leontius and Eupsychius of Cappadocia, or Caecilianus of Africa, or Eustorgius of Italy, or Capito of Sicily, or Macarius of Jerusalem, or Alexander of Constantinople, or Paederos of Heraclea, or those great Bishops Meletius, Basil, and Longianus, and the rest from Armenia and Pontus, or Lupus and Amphion from Cilicia, or James and the rest from Mesopotamia, or our own blessed Alexander, with others of the same opinions as these;–there would then have been nothing to suspect in their statements, for the character of APOSTOLICAL MEN is sincere and INCAPABLE OF FRAUD. (Ad Episcopos 8; A.D. 372,in NPNF2, IV:227)

(NPNF2 = Philip Schaff, et al., editors, A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Church Fathers, 14 volumes, Series 2)

*****

Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman wrote about St. Athanasius’ rule of faith, in his Select Treatises of St. Athanasius, Volume II, 1844 (from his Anglican period):

The recognition of this rule is the basis of St. Athanasius’s method of arguing against Arianism. Vid. art. Private Judgment. It is not his aim ordinarily to prove doctrine by Scripture, nor does he appeal to the private judgment of the individual Christian in order to determine what Scripture means; but he assumes that there is a tradition, substantive, independent, and authoritative, such as to supply for us the true sense of Scripture in doctrinal matters—a tradition carried on from generation to generation by the practice of catechising, and by the other ministrations of Holy Church. He does not care to contend that no other meaning of certain passages of Scripture besides this traditional Catholic sense is possible or is plausible, whether true or not, but simply that any sense inconsistent with the Catholic is untrue, untrue because the traditional sense is apostolic and decisive. What he was instructed in at school and in church, the voice of the Christian people, the analogy of faith, the ecclesiastical [phronema], the writings of saints; these are enough for him. He is in no sense an inquirer, nor a mere disputant; he has received, and he transmits. Such is his position, though the expressions and turn of sentences which indicate it are so delicate and indirect, and so scattered about his pages, that it is difficult to collect them and to analyse what they imply. Perhaps the most obvious proof that what I have stated is substantially true, is that on any other supposition he seems to argue illogically. Thus he says: “The Arians, looking at what is human in the Saviour, have judged Him to be a creature … But let them learn, however tardily, that the Word became flesh;” and then he goes on to show that he does not rely simply on the inherent, unequivocal force of St. John’s words, satisfactory as that is, for he adds, “Let us, as possessing [ton skopon tes pisteos], acknowledge that this is the right ([orthen], orthodox) understanding of what they understand wrongly.” Orat. iii. § 35.Again: “What they now allege from the Gospels they explain in an unsound sense, as we may easily see if we will but avail ourselves of [ton skopon tes kath’ hemas pisteos], and using this [hosper kanoni], apply ourselves, as the Apostle says, to the reading of inspired Scripture.” Orat. iii. 28.

And again: “Since they pervert divine Scripture in accordance with their own private ([idion]) opinion, we must so far ([tosouton]) answer them as ([hoson]) to justify its word, and to show that its sense is orthodox, [orthen].” Orat. i. 37.

For other instances, vid. art. [orthos]; also vid. supr. vol. i. pp. 36, 237 note, 392, fin. 409; also Serap. iv. § 15, Gent. § 6, 7, and 33.

In Orat. ii. § 5, after showing that “made” is used in Scripture for “begotten,” in other instances besides that of our Lord, he says, “Nature and truth draw the meaning to themselves” of the sacred text—that is, while the style of Scripture justifies us in thus interpreting the word “made,” doctrinal truth obliges us to do so. He considers the Regula Fidei the principle of interpretation, and accordingly he goes on at once to apply it.

It is his way to start with some general exposition of the Catholic doctrine which the Arian sense of the text in dispute opposes, and thus to create a præjudicium or proof against the latter; vid. Orat. i. 10, 38, 40 init. 53, ii. § 12 init. 32-34, 35, 44 init., which refers to the whole discussion, (18-43,) 73, 77, iii. 18 init. 36 init. 42, 51 init. &c.; On the other hand he makes the ecclesiastical sense the rule of interpretation, [toutoi] ([toi skopoi], the general drift of Scripture doctrine) [hosper kanoni chresamenoi], as quoted just above. This illustrates what he means when he says that certain texts have a “good,” “pious,” “orthodox” sense, i.e. they can be interpreted (in spite, if so be, of appearances) in harmony with the Regula Fidei.

It is with a reference to this great principle that he begins and ends his series of Scripture passages, which he defends from the misinterpretation of the Arians. When he begins, he refers to the necessity of interpreting them according to that sense which is not the result of private judgment, but is orthodox. “This,” he says, “I conceive is the meaning of this passage, and that a meaning especially ecclesiastical.” Orat. i. § 44. And he ends with: “Had they dwelt on these thoughts, and recognised the ecclesiastical scope as an anchor for the faith, they would not of the faith have made shipwreck.” Orat. iii. § 58.

It is hardly a paradox to say that in patristical works of controversy the conclusion in a certain sense proves the premisses. As then he here speaks of the ecclesiastical scope “as an anchor for the faith;” so when the discussion of texts began, Orat. i. § 37, he introduces it as already quoted by saying, “Since they allege the divine oracles and force on them a misinterpretation according to their private sense, it becomes necessary to meet them so far as to do justice to these passages, and to show that they bear an orthodox sense, and that our opponents are in error.” Again, Orat. iii. 7, he says, “What is the difficulty, that one must need take such a view of such passages?” He speaks of the [skopos] as a [kanon] or rule of interpretation, supr. iii. § 28. vid. also § 29 init. 35 Serap. ii. 7. Hence too he speaks of the “ecclesiastical sense,” e.g. Orat. i. 44, Serap. iv. 15, and of the [phronema], Orat. ii. 31 init. Decr. 17 fin. In ii. § 32, 3, he makes the general or Church view of Scripture supersede inquiry into the force of particular illustrations.

The conclusion is inescapable: St. Athanasius accepts the “three-legged Catholic stool”: Scripture + Church + Tradition. This is not sola Scriptura. J. N. D. Kelly, the Anglican patristic scholar, recognizes this:

So Athanasius, disputing with the Arians, claimed that his own doctrine had been handed down from father to father, whereas they could not produce a single respectable witness to theirs . . .. . . the ancient idea that the Church alone, in virtue of being the home of the Spirit and having preserved the authentic apostolic testimony in her rule of faith, liturgical action and general witness, possesses the indispensable key to Scripture, continued to operate as powerfully as in the days of Irenaeus and Tertullian . . . Athanasius himself, after dwelling on the entire adequacy of Scripture, went on to emphasize the desirability of having sound teachers to expound it. Against the Arians he flung the charge that they would never have made shipwreck of the faith had they held fast as a sheet-anchor to the . . . Church’s peculiar and traditionally handed down grasp of the purport of revelation. Hilary insisted that only those who accept the Church’s teaching can comprehend what the Bible is getting at. According to Augustine, its doubtful or ambiguous passages need to be cleared up by ‘the rule of faith’; it was, moreover, the authority of the Church alone which in his eyes guaranteed its veracity.

It should be unnecessary to accumulate further evidence. Throughout the whole period Scripture and tradition ranked as complementary authorities, media different in form but coincident in content. To inquire which counted as superior or more ultimate is to pose the question in misleading terms. If Scripture was abundantly sufficient in principle, tradition was recognized as the surest clue to its interpretation, for in tradition the Church retained, as a legacy from the apostles which was embedded in all the organs of her institutional life, an unerring grasp of the real purport and meaning of the revelation to which Scripture and tradition alike bore witness. (Early Christian Doctrines, San Francisco: HarperCollins, revised edition, 1978, 45, 47-48)

***

(originally 6-16-03)

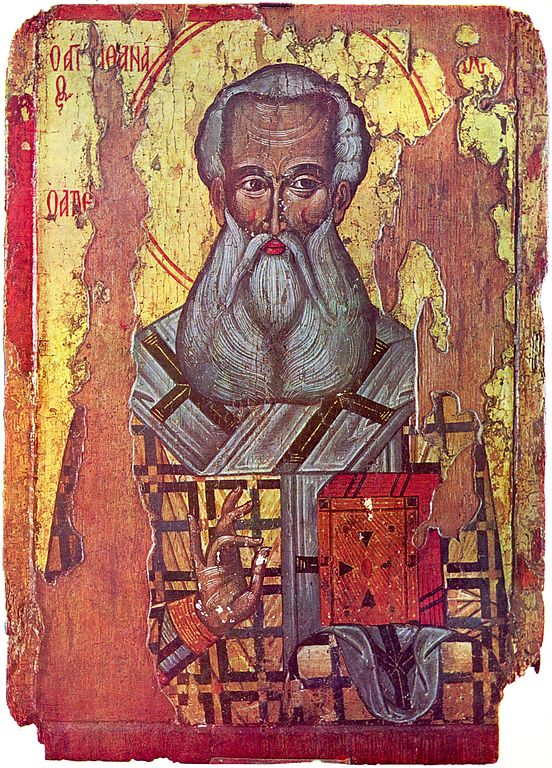

Photo credit: St. Athanasius (296-373): icon from Sozopol, Bulgaria, end of 17 century [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***