[see full information for the book above]

An apologia is a “defense” or elaborate explanation of something. An apologist is “one who defends” (in this case, Christianity or Christian doctrine). Apologetics is the field which involves the “rational defense of Christianity” (in my case, often Catholic Christianity in particular). A Catholic friend (words in blue) made some negative comments about apologists that I disagreed with. The following are my spontaneous observations about the community I am involved in and the field I have devoted my life to.

* * * * *

Too many apologists (Catholic or Protestant) have completely lost sight of the goal (which is Christ) and have replaced it with “I win, you lose” — victory at all costs. Apologists are often making this bed they sleep in.

Now you got me onto one of my pet peeves (being an apologist myself). I have several thoughts about this. First of all, I don’t see the point in sweeping judgments upon a whole class of people, such as the following:

1. Apologists are arrogant folks who condemn others who disagree.*

2. Apologists are objectionable because they defend one view over another and thus insult people and make them feel uncomfortable. This is uncharitable.

3. Apologists lack love and just want to win the argument.

4. Apologists are know-it-alls.

Etc.

I don’t see that this accomplishes anything. It is prejudicial language, to start with, because it is too sweeping. And this is what so often takes place on that one particular discussion board where apologists are constantly bashed. It got so bad that it actually made me give up discussion boards altogether, because one Orthodox fellow started insulting me to such an extent that he made out that my very vocation as a full-time apologist was “nothing to be proud of” and that I was by nature some sort of “academic pretender” and charlatan, who should get a “real job.” This actually happened.

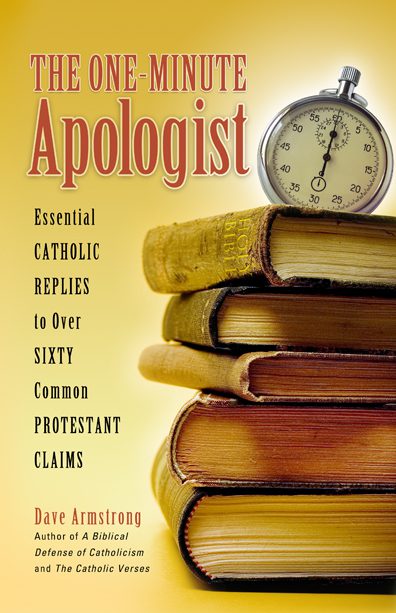

My response was to point out that 1) I have never claimed to be a scholar in the first place (quite the contrary: I take great pains to reiterate that I am not, in places like introductions to my books), and 2) the greatest, most well-known apologists were not formally theologically trained; they were “amateurs” (Lewis, Chesterton, Muggeridge, Howard, Kreeft). Chesterton did not even have a college degree of any kind.

This sort of tripe is pure prejudice. Any charge that can be made about apologists can be made of any class of people or of people in general. And so it becomes a meaningless discussion, as it is about human nature, not one group of people. Are apologists prideful? Certainly, but I don’t think any more so (or at least not greatly more so) than anyone else, since we all have to struggle with pride. Can we be more charitable? Certainly, as can every human being on the face of the earth.

Do we like to “win arguments”? I should hope so, as argument is necessarily entailed in defending one position over against another (and that usually involves a in human beings certain energetic “fighting” or “competitive” spirit, as in any contest), and this is entirely biblical (Paul arguing and disputing in the temples and academies alike; Jesus’ many disputatious conversations, especially with the Pharisees, etc.).

Of course, I agree that the goal is not to “win” as an end in itself. Any apologist who does not know this is not worthy of the name, and not worth his salt. The goal is truth and persuasion, and conversion and an advance in knowledge and the spiritual life, and “Christ”, as you say. This is what the Apostle Paul tried to do. And we ought to be learners as well as teachers. That’s why I am so big on dialogue (which you seem to not like much, for some reason unknown to me).

I don’t see myself as the “superior” lecturing “subordinates.” I see myself as an equal alongside the person I dialogue with. This is precisely why I don’t like to lecture and why I rarely give public talks. I like to have conversations with people, not lecture them. I can learn from my discussion partner, and he can learn from me. We can both arrive at a fuller awareness of truth by throwing ideas back and forth and testing them. This is classic Socratic dialogue, and I am an enthusiastic advocate of it.

But I find that a lot of the animus against apologists comes from almost universal human insecurity and the rampant relativism of our culture. People aren’t supposed to be “confident” in a viewpoint (particularly religious ones) because 1) that goes against relativism and so-called “confidence”, and 2) it supposedly makes the person who possesses such confidence arrogant by the very possession of it (because so many people are insecure emotionally and intellectually, and “unsure” of things).

This doesn’t follow. If you believe something is true, and believe it in faith, then you will defend it until shown a better way. That is not arrogance; it is simply common sense and the only way things can be, short of adopting a wholesale relativism or cynical “who cares about anything?” attitude.

So we apologists often get a bum rap. There are a lot of rookie or amateur apologist who conduct themselves in less-than-desirable ways, of course. I’m not denying that, and one would expect it. But I have not see nearly the amount of arrogance and hubris that we are so often accused of. The well-known Catholic apologists I have met (and I have met virtually all of them by now) are almost without exception very nice people.

Yes, I do see some arrogance at times (in myself as well, and I will correct things and retract statements and have removed many entire papers), but I don’t see that it is a leading characteristic, to such an extent that apologists must be pilloried and mocked and the very endeavor frowned upon as some unsavory thing (as it is, so often).

I think the reasonable thing here is to cease the prejudicial, sweeping-type language and get very specific. If I get a letter (as I do once in a while, but not all that often), stating that I am too uncharitable and.or too sarcastic, it rarely gives specific examples. But how can I change if I don’t have those? Of what use is such a letter? So someone says, “you are too sarcastic.” But I have written hundreds of thousands of words.

Surely, not all of that reeks of this shortcoming. If that were true, I wouldn’t receive the dozens of letters commending me for my charitableness (even from a great many Protestants). At some point, it is a subjective judgment. And it may be an untrue opinion. It is not self-evidently true simply because someone gives their opinion that they find someone else uncharitable.

So I always ask for specific examples, with some sort of rational argument as to why the person thinks I went too far. In many instances, I will be happy to change or remove something because it lacks charity (upon reflection). But how can I possibly do that if I get a general remark like “your writing is too sarcastic [or harsh, or whatever the charge may be]”? People often do not even understand what sarcasm is, let alone what the proper use of it might be (and I argue that Jesus and Paul used it and commanded us to imitate them, so I use it, too, where it is warranted).

It’s like “arguing” that “lawyers [i.e., as a class, or characteristically] are unconcerned with truth and only with victory” or “used car salesman are liars” or any number of racial or ethnic stereotypes. What good does that do? So I challenge you as well to produce some examples of apologists who want to “win at all costs.” Name names and give examples. And if you can do that, you ought to use that energy to write to those people themselves and correct them in brotherly love, rather than make sweeping statements which don’t accomplish much except to perpetuate hostility (I think, most unfairly).

Beyond all that (which are my own observations, from now 23 years of doing both Protestant and Catholic apologetics), the fact remains that all “apologist”means is “one who defends the faith.” This is a biblical command, and all must do it (1 Peter 3:15-15; Jude 3). There are degrees, of course. I am now a professional, and get extremely in-depth. Others may describe their faith in a childlike way that is equally valid in its time and place.

But it is foolish to run down something that all Christians are duty-bound to do, to the extent that their abilities and knowledge allow. I have a chapter in one of my books on “the biblical basis of apologetics.” So I say that if people want to run it down and judge entire classes of people, they ought to also examine what the Bible teaches about it (or, for that matter, Vatican II and the Catechism). That is where the discussion should take place (but rarely does).

Some people find apologetics inherently divisive and arrogant or something, because it involves (as a defense of truth against error) pitting one set of beliefs against another.

It once drove me bonkers when I found religious (priests, bishops) that would not tolerate apologists. Now I rather understand. Apologetics is not inherently divisive, just as money isn’t inherently evil. But as soon as you lose perspective and propriety — both often become tools of the devil (like so many other abused gifts).

Unless I see examples, how can I respond to such a charge? As a truism or proverb, of course I agree:

1) “Apologetics can be abused.”

*

2) “Apologists can become arrogant if they ‘win too many arguments.’ ”

3) “Apologists might start to absurdly think that conversions come from their brilliance as opposed to the Spirit of God.”

Etc.

But these are all self-evident truths. The criticisms can also become just as arrogant (as I experienced myself). When critics refuse to give examples or to correct individual persons when they really need correction, and instead just talk about them in gossipy fashion, and distort what they are arguing, I find that far more offensive and arrogant and uncharitable than the great bulk of apologetics I observe.

So who are these people you are talking about, if they are legion? I can see how it readily applies to anti-Catholic Protestant apologists, but not to ecumenical Protestant apologists or Catholic apologists en masse. There are a few Catholic apologists I observe who I personally think have a bit of a pride problem or arrogant streak, but again, how is that different from any class of people?

I think that academics, for example, are far more prone to arrogance and snobbery than apologists are (if we must speak in such terms at all). I’ve heard many many nurses complain of the arrogance and snobbishness of the doctors they work for. In the end, one must analyze individual cases.

Indeed, Jesus and Paul may have been controversial but (a) by the standard of my own authority paper, it is “men of God” such as these that are the ones who truly “make waves” and (b) both Jesus and Paul stressed “not giving offense” (Matthew 17:24) and “being all things to all people” (1 Cor 9:20-22).

But Jesus also said “you will be hated by all for my name’s sake,” and “a son will be set against his mother,” etc. We can proof-text all day long. I have lived by the maxim “be all things to all people” throughout my entire career as an amateur and professional apologist. I believe that very strongly. But that doesn’t mean at all that, therefore, I will not become involved in controversy or become unpopular in some circles.

Anyone who proclaims unpopular truths becomes unpopular with some folks! It’s inevitable. It goes with the territory. We should fully expect it and even welcome it as a good sign — provided it is the message which offends, and not our lousy presentation of it, or (heaven forbid) obnoxious or offensive, overbearing aspects of our personality.

When you argue that one view is right and another wrong, people will be offended. It’s as simple as that. If I were popular and loved by every Protestant on the face of the earth, I would suspect I am terribly failing at communicating my message. As it is, we find precisely what I would expect to find: anti-Catholics (I am thinking particularly of some of their major apologists) despise me; loathe me, because what I defend is what they detest, and because I shoot down their arguments. So they despise me.

Ecumenical Protestants, on the other hand (judging from my correspondence), react in an entirely different manner. They seem to respect what I am doing, benefit from it, recognize my work as charitable for the most part and not “anti-Protestant.” I’m the same old person, but I receive these wildly different reactions. It’s not that difficult to figure out why that is.

Anti-Catholics love “dumb” Catholics, because they make their argument for them and can be used as stooges and clowns, as examples of what Catholics as a group supposedly are, or what the system produces. But cross them and show their arguments to be fallacious and false, and it is quite a different story. So I am willing to be unpopular with those folks, and if I wasn’t, I would be suspicious.

I think there is a middle road: one taken by Vatican II: we can be both apologetic and ecumenical without compromise, but present our beliefs in a charitable way that Protestants can better understand. 1 Peter 3:15-16 and Paul’s “be all things to all people so that by all means you may win some.”

Agreed.

Some Catholics will publicly doubt (or seem to doubt, or publicly wax inconclusively, or question too much) dogmas or binding moral teachings of the Catholic Church, such as papal infallibility or the ban on contraception. That makes them quite popular with Protestants (and sometimes Orthodox, too), who respect such a person as a sterling example of honesty and open-mindedness and intellectual guts because he rejects one of the “absurdities” that they see in Catholic orthodoxy. Such a person is being an inconsistent Catholic and in so doing will win the accolades and rapt admiration of the non-Catholic folks. Catholics like this are very well-liked and popular among non-Catholics!

And if we want to talk about pride, I think someone could easily fall into priding himself on being so well-liked, and that they might have some arrogance in discussing more “controversial” folks like myself, implying that their unpopularity might be due to them personally rather than their ideas which offend? And that such people would be reluctant to defend people like me publicly for fear of offending the Protestants and jeopardizing their position as the “nice and respectable guy”? This is human nature. I majored in sociology and minored in psychology. I learned a little in those classes (not much, but some things about people).

One might also argue that it helps humility and prevents pride to be constantly subjected to a stream of invective, insults, and epithets, as I and many Catholic apologists are, from the anti-Catholics. Protestant and Catholic apologists alike get this abuse from liberals in their own ranks (or fideists who frown upon applying reason to faith) and from agnostics and atheists. It takes some humility to just sit there and take that sort of thing.

Pride is a very tricky thing, perfected by the devil over many centuries, and not easily summarized. So I think that an excessively “conciliatory” approach can be exploited by the devil just as easily and as quickly as he could exploit a “triumphalistic / arrogant / win at all costs” apologist-type (i.e., the stereotype or caricature of the apologist, or a truly lousy example of one).

I (hanging my head in shame as I admit this) am one of those weird, odd, “triumphalist”, supposedly anti-ecumenical “apologists” myself (even — GASP! –full-time these days, by the grace of God).

I’ve had two people in the last month (an Orthodox and a Reformed pastor) tell me that this is “nothing to be proud of” and that I should “get a real job.” The insulting nature of such rhetoric is its own refutation.

I do what I do because of the following reasons:

1. I was called to it as a matter of vocation. I knew this as far back as 1981, as an evangelical Protestant. When I converted in 1990 it was clear that I should keep writing and doing apologetics as a Catholic, just as I had been doing for nine years.

2. The Bible commands all believers to defend their beliefs and share them intelligently and charitably with others (e.g., 1 Peter 3:15-16; Jude 3). It stands to reason that some few would do this full-time and “professionally.” We are merely specializing in what all Christians should do to some degree.

3. I happen to believe that a faith backed up by reason and knowledge of the usual and traditional attacks upon it is a stronger, and more biblical and Catholic faith. Jesus commanded us to love God with all our heart, soul, strength, and mind. I do apologetics because it strengthens people’s faith (as well as my own, very much so) and removes obstructions and roadblocks to faith. I fail to see what is bad about that.

There is nothing like receiving a letter from someone who says that they have returned to the Church or converted to it or were otherwise spiritually strengthened or educated by something you wrote. To God be all the glory for that! But I refuse to sit here and have to apologize (no pun intended!) for what I do when it is being used by God in some small way for His purposes (as evidenced by the letters I receive, success of books, etc.).

4. I do not do what I do for fame, glory, money () or the accolades of men (a steady stream of insults from the anti-Catholics — and even from some fellow Catholics — keep me humble enough). I don’t do it because I think I am better or smarter than anyone else, or because all other views are worthless, or because I think that the intellectual aspect of faith is more important than any other aspect.

5. I am just as committed to warm relationships with non-Catholics as I am to defending Catholic distinctives. I don’t see how the two are mutually-exclusive at all (though they are often made out to be).

6. Lastly, there seems to be this motif or strain of thought lately, to the effect that apologists are somehow “academic pretenders” and acting as if they have all the answers and demanding of the respect that a scholar should receive (on the grounds that he ought to receive it). I don’t know where this comes from. It is certainly not true in my case (and I have not seen it in any other apologist that I know of).

I have taken the greatest pains to emphasize that I am not a scholar, but just a lay apologist without formal theological education. My opinions are to be accepted insofar as they are deemed to be true, biblically supported, successfully explicated through reason, historically- and magisterially-backed up and helpful; no more, no less.

I have also pointed out that the greatest and most influential apologists of recent times were also mere amateurs in their field. C.S. Lewis had no formal theological training. G.K. Chesterton did not, either. He was a journalist, without any college degree. Malcolm Muggeridge was a journalist. Peter Kreeft is a philosophy professor; Thomas Howard an English Professor, etc. Scholars write largely to other scholars. Apologists write to the masses and the common man. Both are valid endeavors (I love scholars and scholarship and utilize this as much as I can, in my work); they are simply different; they have differing natures and purpose.

I would much rather fight the errors of our time than have to state things like this in defense of my own vocation. But I thank everyone for letting me spout and vent a bit.

Believe it or not, apologists have feelings too! And I suspect that we like to be appreciated for what hard work we do (usually for relatively little financial reward, or none, in the case of the many who do apologetics besides their regular jobs, as I did for about 17 years) just as much as the next man. That’s not why we do our work, hopefully, but we are human beings, and get tired of the false, wrongheaded criticisms every once in a while. Good criticism on particulars is fine, of course, but this generalizing, condescending nonsense about “triumphalism” and so forth is worthless, both in and of itself, and in terms of achieving any positive, constructive purpose.

***

As I see it, apologetics is to theology what first-aid is to medicine. An apologist is like a paramedic who arrives on the scene of an injury and uses specialized skills to help stabilize the patient and make sure he or she can be delivered — alive — into the competent hands of physicians who can provide long-term, high-level medical care that will save the patient’s life. The paramedic’s role is lowly when compared with the role of the surgeon, but his role is, nonetheless, important.The paramedic, like his wartime counterpart on the battlefield, the medic, is not a physician, he isn’t a surgeon. He doesn’t pretend to be in the category of a cardiologist or oncologist or surgeon, but he does have a useful and necessary role in the Big Picture. He helps ensure that the physicians can perform their specialized work on the patient. But if the patient dies on the scene of the accident, the physician has no patient.

Many, many Catholics these days are reeling under the effects of challenges from non-Catholic proselytizers. I know. I meet them by the hundreds at parishes around the country. They’ve lost sons and daughters to the Watchtower or the local Evangelical mega-church down the street. Co-workers, friends, family — they’ve seen people dear to them reject the Catholic Church and head elsewhere, often with a bitter anti-Catholicism roiling inside them. These people need help. That’s the province of practical, popular apologetics, to help people come to understand the answers to the challenges they and their loved ones face. Someone has to help. The trustworthy, orthodox, dedicated apologists I know are doing what they can to help.

People should also understand that apologists typically, are not theologians (Scott Hahn being a notable exception). They usually have at least some formal training in theology, typically at the graduate level, to inform and conform their practical experience to the authentic Magisterium.

What sometimes puzzles me is how worked up some people become when the subject of apologetics (and apologists) arises. I’ve read some pundits who bemoan the so-called “cult of the expert.” They fret and fume and wring their hands over the popularity of apologists such as Tim Staples or Scott Hahn or Karl Keating. Is it because they sell a ton of books? Is it because their name on the bill can pack a parish auditorium with hundreds of hungry Catholics on a cold, snowy Tuesday evening in Lansing or Hoboken? Maybe. Maybe not.

But one thing I do know: Mainstream, reputable, and orthodox Catholic apologists, such as the men named above, are simply trying to live out the call of Vatican II, the mandate for lay Catholics to do what they can, according to their own temperament, circumstances, and abilities, to further the life and mission of the Church. That’s the authentic role of apologetics, as I see it. To help. To be in and with the heart of the local Church, performing a needed, if lowly, function in the Body of Christ (cf. 1 Cor. 12).

As an apologist, I have no presumptions — zilch — of somehow encroaching on the territory of the theologians. I respect and am indebted to the theologians (speaking here about those who are orthodox and faithful to the magisterium, not the Monika Helwig, Richard McBrien, Charles Curran, Rosemary Reuther rabble) for their teaching and expertise — an expertise I don’t have but from which I benefit. Some apologists, such as Hahn and Kreeft, inhabit the academy as well as the world of practical apologetics, but they are the exceptions.

Most of us “apologists” are just plain folks like anyone else. Catholics who love the Church and want to do what we can to help people who are badgered and battered by the arguments and misinformation leveled at them by some aggressive Fundamentalists, Evangelicals, Mormons, and JWs (who, of course, we do not lump into the same category).

We take seriously Vatican II’s exhortations to lay people to do what they can to help the Church. This section from Apostolicam Actuositatem summarizes the point I’m hoping to make with these comments:

Since, in our own times, new problems are arising and very serious errors are circulating which tend to undermine the foundations of religion, the moral order, and human society itself, this sacred synod earnestly exhorts laymen–each according to his own gifts of intelligence and learning–to be more diligent in doing what they can to explain, defend, and properly apply Christian principles to the problems of our era in accordance with the mind of the Church.(Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity, 2.6)

[O]ne of the great mysteries of church life to me is how some folks can’t quite grasp the lesson of this past Sunday’s second reading: you know, many parts, one body.”Apologetics” is…apologetics. It’s not theology. It’s not spirituality. It’s apologetics, which means it serves a certain purpose not served by other styles of religious discourse.

Very briefly, apologetics exists to answer questions and to address challenges, not to unpack the depths of theological resonance in various penumbras of doctrinal formulations.

Apologetics does not exist to replace theological thinking or spiritual reflection, although I do get concerned sometimes that with the current popularity of apologetics, we are sometimes tempted to forget that.

But the point is simply this: apologetics exists because people ask questions. They want to know how you, a reasonable person could actually hold belief in God to be reasonable. They want to know how you seriously could consider yourself a Christian, although you admit to being a Catholic. Apologetics answers those questions in the context in which they are asked. What is the alternative? Change the subject?

. . . [I]t seems fairly clear to me that in a culture in which basic Christian faith is widely derided as unreasonable and Catholicism in particular is regarded as false, there is a tremendous need to answer those questions. The answering is like any step the intellect takes towards belief. It is not the belief itself. It opens the door to belief. And why is that a problem?

***

(originally 1-29-04)

***