This is an installment of a series of replies (see the Introduction and Master List) to much of Book IV (Of the Holy Catholic Church) of Institutes of the Christian Religion, by early Protestant leader John Calvin (1509-1564). I utilize the public domain translation of Henry Beveridge, dated 1845, from the 1559 edition in Latin; available online. Calvin’s words will be in blue. All biblical citations (in my portions) will be from RSV unless otherwise noted.

Related reading from yours truly:

Biblical Catholic Answers for John Calvin (2010 book: 388 pages)

A Biblical Critique of Calvinism (2012 book: 178 pages)

Biblical Catholic Salvation: “Faith Working Through Love” (2010 book: 187 pages; includes biblical critiques of all five points of “TULIP”)

*****

IV, 7:10-11

***

CHAPTER 7

*

the kind of jurisdiction which belonged to the Roman Bishop one narrative will make manifest. Donatus of Casa Nigra had accused Cecilianus the Bishop of Carthage. Cecilianus was condemned without a hearing: for, having ascertained that the bishops had entered into a conspiracy against him, he refused to appear. The case was brought before the Emperor Constantine. who, wishing the matter to be ended by an ecclesiastical decision; gave the cognisance of it to Melciades, the Roman Bishop, appointing as his colleagues some bishops from Italy, France, and Spain. If it formed part of the ordinary jurisdiction of the Roman See to hear appeals in ecclesiastical causes, why did he allow others to be conjoined with him at the Emperor’s discretion?

Why is cooperation with other bishops ruled out by virtue of having a supremacy? It is not. In fact, this is exactly what the facts of the matter show:

In 313 the Donatists came to Constantine with a request to nominate bishops from Gaul as judges in the controversy of the African episcopate regarding the consecration in Carthage of the two bishops, Cæcilian and Majorinus. Constantinewrote about this to Miltiades, and also to Marcus, requesting the pope with three bishops from Gaul to give a hearing in Rome, to Cæcilian and his opponent, and to decide the case. On 2 October, 313, there assembled in the Lateran Palace, under the presidency of Miltiades, a synod of eighteen bishops from Gaul and Italy, which, after thoroughly considering the Donatist controversy for three days, decided in favor of Cæcilian, whose election and consecration as Bishop of Carthage was declared to be legitimate. (Catholic Encyclopedia, “Pope St. Miltiades”)

nay, why does he undertake to decide more from the command of the Emperor than his own office? But let us hear what afterwards happened (see August. Ep. 162, et alibi). Cecilianus prevails. Donatus of Casa Nigra is thrown in his calumnious action and appeals. Constantine devolves the decision of the appeal on the Bishop of Arles, who sits as judge, to give sentence after the Roman Pontiff. If the Roman See has supreme power not subject to appeal, why does Melciades allow himself to be so greatly insulted as to have the Bishop of Arles preferred to him? And who is the Emperor that does this? Constantine, who they boast not only made it his constant study, but employed all the resources of the empire to enlarge the dignity of that see. We see, therefore, how far in every way the Roman Pontiff was from that supreme dominion, which he asserts to have been given him by Christ over all churches, and which he falsely alleges that he possessed in all ages, with the consent of the whole world.

Who is to say that Constantine was not possibly overreaching his bounds? Caesaropapism was a frequent tendency of the Byzantine Emperors. Again, there is more than one way to view anything. Calvin sees some of the actions of Constantine and concludes that they suggest a lack of supremacy of the bishop of Rome. But they could just as easily suggest that the emperor is not properly informed as to the proper government of the Church. Yet the actual historical evidence indicates that the emperor was aware of the preeminence of the pope, even in this council, for he wrote to the pope:

[Y]our reverence will decide how the aforesaid case may be most carefully examined and justly determined . . . (Arnold Hugh Martin Jones, Constantine and the Conversion of Europe, University of Toronto Press, p. 94)

Note that the decision was finally made by the pope, not the collection of bishops. Professor Jones casually notes about this council: “to preside over them he appointed Miltiades, bishop of Rome” (p. 94). And he observes:

The court . . . consisted not only of the four bishops of Rome, Cologne, Autun and Arles, whom Constantine had nominated, but of fifteen others from various Italian sees. The Pope had insisted that the proposed imperial commission of enquiry be transformed into a church council. (Ibid., p. 95)

Technically, since this was not an ecumenical council, other local councils dealing with the same matter are not unusual, let alone unthinkable. If the pope had ratified the decisions of an ecumenical council, there would be no appeal. So Calvin’s argument is not nearly sufficient to bring down papal supremacy, as he thinks it is.

Though the famous Emperor Constantine wrongly seems to have regarded the council of Rome as a body of imperial commissioners, he still accepted its conclusions and scolded the Donatists for spurning it (see Jones, p. 96). For some reason (perhaps again exhibiting an inadequate understanding of Catholic ecclesiology) he allowed their appeal to the Council of Arles. And the Donatists were appealing to the secular ruler rather than to the Church. In any event, the council of Arles agreed (unanimously) all down the line with the Roman council, and in no sense superseded or judged it. The Donatists were again condemned.

Most telling of all, however, and a fatal blow to Calvin’s use of this incident for his “anti-Roman” polemic, is the fact that Constantine also did not accept the verdict of Arles as (legally) conclusive, and agreed to hear yet another appeal of the Donatists, himself:

Constantine once again gave in to the Donatist demands and agreed to hear their case personally. Dismissing the bishops from Arles, he ordered both Caecilian and his accusers to his court, where they attended his pleasure for the better part of a year. (Constantine and the Bishops, Harold Allen Drake, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000, p. 220)

In other words, Constantine went beyond, not only papal supremacy, but even conciliarism, such as is believed by the Orthodox: straight to a notion of a caesaropapist State-Church, as seen in Lutheranism, where princes replaced bishops. Thus it proves too much to appeal to his example. Calvin’s argument collapses, once we accept these additional relevant facts (which he conveniently omits from consideration).

If we follow what Constantine did, then it would be an argument for no Church government whatever (if legitimate church councils cannot even decide matters of heresy with finality). It would defeat Calvin’s own ecclesiology as well as (supposedly) the Catholic position. Constantine was outside of his proper jurisdiction. But such is the danger of too much political power, ultimately unchecked by anyone else.

I know how many epistles there are, how many rescripts and edicts in which there is nothing which the pontiffs do not ascribe and confidently arrogate to themselves. But all men of the least intellect and learning know, that the greater part of them are in themselves so absurd, that it is easy at the first sight to detect the forge from which they have come. Does any man of sense and soberness think that Anacletus is the author of that famous interpretation which is given in Gratian, under the name of Anacletus—viz. that Cephas is head? (Dist. 22, cap. Sacrosancta.) Numerous follies of the same kind which Gratian has heaped together without judgment, the Romanists of the present day employ against us in defence of their see. The smoke, by which, in the former days of ignorance, they imposed upon the ignorant, they would still vend in the present light. I am unwilling to take much trouble in refuting things which, by their extreme absurdity, plainly refute themselves.

Catholics and Protestants and secular scholars alike all now agree that the notorious “false decretals” were forgeries. The Catholic case for the papacy rests on much, much more than this, and indeed, Catholics realized the falsity of texts before Calvin and Luther were ever born:

The Middle Ages were deceived by this huge forgery, but during the Renaissance men of learning and the canonists generally began to recognize the fraud. Two cardinals, John of Torquemada (1468) and Nicholas of Cusa (1464), declared the earlier documents to be forgeries, especially those purporting to be by Clement and Anacletus. Then suspicion began to grow. Erasmus (died 1536) and canonists who had joined the Reformation, such as Charles du Moulin (died 1568), or Catholic canonists like Antoine le Conte (died 1586), and after them the Centuriators of Magdeburg, in 1559, put the question squarely before the learned world. . . . In 1628 the Protestant Blondel published his decisive study, “Pseudo-Isidorus et Turrianus vapulantes”. Since then the apocryphal nature of the decretals of Isidore has been an established historical fact. The last of the false decretals that had escaped the keen criticism of Blondel were pointed out by two Catholic priests, the brothers Ballerini, in the eighteenth century. (Catholic Encyclopedia: “False Decretals”)

I admit the existence of genuine epistles by ancient Pontiffs, in which they pronounce magnificent eulogiums on the extent of their see. Such are some of the epistles of Leo.

Good. At least Calvin is aware of this, and acknowledges it.

For as he possessed learning and eloquence, so he was excessively desirous of glory and dominion; but the true question is, whether or not, when he thus extolled himself, the churches gave credit to his testimony?

Most did; some did not, as we would expect, because the presence of a truth or a fact does not automatically cause all men to accept it.

It appears that many were offended with his ambition, and also resisted his cupidity. He in one place appoints the Bishop of Thessalonica his vicar throughout Greece and other neighbouring regions (Leo, Ep. 85), and elsewhere gives the same office to the Bishop of Arles or some other throughout France (Ep. 83). In like manner, he appointed Hormisdas, Bishop of Hispala, his vicar throughout Spain, but he uniformly makes this reservation, that in giving such commissions, the ancient privileges of the Metropolitans were to remain safe and entire. These appointments, therefore, were made on the condition, that no bishop should be impeded in his ordinary jurisdiction, no Metropolitan in taking cognisance of appeals, no provincial council in constituting churches. But what else was this than to decline all jurisdiction, and to interpose for the purpose of settling discord only, in so far as the law and nature of ecclesiastical communion admit?

Apples and oranges . . . the ordinary jurisdiction of bishops in their own domain does not annihilate the universal jurisdiction of the pope. There is also a sense of “delegated authority.” Hence, Leo the Great wrote to Anastasius, Bishop of Thessalonica:

If with true reasoning you perceived all that has been committed to you, brother, by the blessed apostle Peter’s authority, and what has also been entrusted to you by our favour, and would weigh it fairly, we should be able greatly to rejoice at your zealous discharge of the responsibility imposed on you.

Seeing that, as my predecessors acted towards yours, so too I, following their example, have delegated my authority to you, beloved: so that you, imitating our gentleness, might assist us in the care which we owe primarily to all the churches by Divine institution, and might to a certain extent make up for our personal presence in visiting those provinces which are far off from us: for it would be easy for you by regular and well-timed inspection to tell what and in what cases you could either, by your own influence, settle or reserve for our judgment. For as it was free for you to suspend the more important matters and the harder issues while you awaited our opinion, there was no reason nor necessity for you to go out of your way to decide what was beyond your powers. . . .

Therefore according to the canons of the holy Fathers, which are framed by the spirit of God and hollowed by the whole world’s reverence, we decree that the metropolitan bishops of each province over which your care, brother, extends by our delegacy, shall keep untouched the rights of their position which have been handed down to them from olden times: but on condition that they do not depart from the existing regulations by any carelessness or arrogance. . . .

Concerning councils of bishops we give no other instructions than those laid down for the Church’s health by the holy Fathers: to wit that two meetings should be held a year, in which judgment should be passed upon all the complaints which are wont to arise between the various ranks of the Church. But if perchance among the rulers themselves a cause arise (which God forbid) concerning one of the greater sins, such as cannot be decided by a provincial trial, the metropolitan shall take care to inform you, brother, concerning the nature of the whole matter, and if, after both parties have come before you, the thing be not set at rest even by your judgment, whatever it be, let it be transferred to our jurisdiction. (Letter XIV)

Thus it is yet another instance of the typically Protestant and Calvinist “either/or” mentality. Calvin sees local jurisdiction of bishops and illogically assumes that it is some sort of disproof of universal papal jurisdiction. It is not (neither logically nor historically). But apparently Calvin thinks that if he repeats a falsehood enough times, it will become true.

(originally 6-25-09)

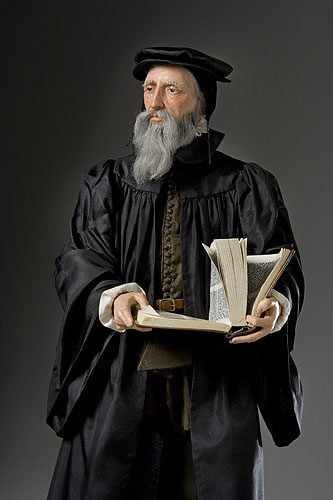

Photo credit: Historical mixed media figure of John Calvin produced by artist/historian George S. Stuart and photographed by Peter d’Aprix: from the George S. Stuart Gallery of Historical Figures archive [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

***