[drawn from various articles and books of mine, as a summary]

*****

The bulk of Newman’s extraordinary work is devoted to the exposition of a series of analogies, showing conclusively that the Protestant static conception of the Church (both historically and theologically) is incoherent and false. He argues, for example, that notions of suffering, or “vague forms of the doctrine of Purgatory,” were universally accepted, by and large, in the first four centuries of the Church, whereas, the same cannot be said for the doctrine of original sin, which is agreed upon by Protestants and Catholics.

Protestants falsely argue that purgatory is a later corruption, but it was present early on and merely developed. Original sin, however, was equally if not more so, subject to development. One cannot have it both ways. If purgatory is unacceptable on grounds of its having undergone development, then original sin must be rejected with it. Contrariwise, if original sin is accepted notwithstanding its own development, then so must purgatory be accepted. [“Development of Doctrine: A Corruption of Biblical Teaching?”: published in The Catholic Answer, Sep. / Oct. 1995]

The Jews offered atonement and prayer for their deceased brethren, who had clearly violated Mosaic Law. Such a practice presupposes purgatory, since those in heaven wouldn’t need any help, and those in hell are beyond it. The Jewish people, therefore, believed in prayer for the dead (whether or not this book is scriptural; Protestants deny that it is). [A Biblical Defense of Catholicism, May 1996]

Here I gave the precise reason why some semblance of purgatory must have been presupposed. For the Reformed tradition, as well as for most Protestants, save a few like C. S. Lewis or John Wesley, there is no third state after death (after Christ’s death and resurrection and ascension). Only heaven and hell exist, and it is useless and meaningless to pray for souls in either, as I argued in the passage.

Therefore, the question is, why did the Jews “pray for the dead” and “make atonement for the dead” as the passage in 2 Maccabees states? They did because they assumed that the dead were still in some sort of state in which they could be aided by intercessory prayer. And that can only be a third state besides heaven and hell. This is what the people whose practice is described must have believed. It doesn’t require a fully developed notion of purgatory; only an intermediate state of some sort besides heaven and hell: a place where they can still be helped by prayer on their behalf.

An argument could be made (over against this scenario) for retroactive prayer (since God is outside of time and can quite arguably apply and answer prayers regardless of whether a person is dead) — even Martin Luther held to something like this. That leaves only some kind of third state as an explanation of prayer for the dead as historical Jewish practice.

That I was not holding that biblical descriptions evidence purgatory in its developed dogmatic form, was made very clear in my later commentary in this book on Luke 16:19-31 (Lazarus and the rich man) and three related passages:

At the very least, these passages prove that there can and does exist a third, intermediate state after death besides heaven and hell. Thus, purgatory is not a priori unthinkable from a biblical perspective (as many Protestants casually assume). True, the Hebrew Sheol is not identical to purgatory (both righteous and unrighteous go there), but it is nevertheless strikingly similar.

***

Like “the Holy Trinity,” “purgatory” is a term not occurring in Scripture, but the reality it refers to is implied by scriptural truths. [The Catholic Answer Bible, 2002]

Authority in the early Church was developing just as the biblical canon and Christology and Mariology and purgatory and prayers for the dead and original sin and everything else were developing. [1-10-04]

Of course we won’t find a fully developed medieval conception of purgatory [in 1 Cor 3], but it is foolish to expect that anyway, just as it would be to expect to find full Chalcedonian Christology and trinitarianism in all its glorious nuanced complexity. That is true of all doctrines, so why should purgatory be an exception? [3-3-07]

I habitually either qualify or presuppose doctrinal development or make clear in context that I am not claiming that Scripture “proves” a full-blown doctrine of purgatory. Hence, I used to have a paper up, entitled, “50 Bible Passages On Purgatory and Analogous Processes”.

The very title shows that I was not maintaining that each passage was explicit, and that there were analogies of process that suggested the concept of purgatory.

The Bible indeed provides much evidence or indication of purgatory. I collected 25 passages in A Biblical Defense of Catholicism, complete with massive support of Church fathers, who certainly believed that purgatory was in mind in these passages. But that is different from a position that would deny any development occurred. “Evidence” is not used in this sense to mean “absolute proof.”

A hundred times in my writings, I’ve stated that the Catholic notion of “biblical evidence” is not absolute proof, but rather, consistency and harmony with Scripture and a given doctrine, including implicit and indirect, deductive indications. Here are some of the numerous examples:

As to Tertullian seeking to ground all doctrine in Scripture, or harmonious with Scripture (meaning that there may not always be explicit proofs, as Chemnitz himself later concedes with regard to, e.g., infant baptism) we have no disagreement. Catholics believe the same. (8-29-07)

The tradition of man here is sola Scriptura and the silly notion that absolutely everything Christians believe must be explicitly laid out in the Bible. There is no Bible passage that says that, so it is a tradition of man if there ever was one. Nor is there any passage that lists the books of the Bible. The canon is an extrabiblical doctrine and tradition that requires Church authority to accept. But all Catholic doctrine is completely consistent and harmonious with Scripture. . . . Now you show us where the Bible teaches that every truth has to specifically be backed up by a Bible proof text. I’ll save you the trouble. You can’t do it. (3-19-11)

This is how we ultimately know what is true: it will be harmonious with Scripture, and it will also be a tenet that the Church has always held, in kernel or more fully developed through time. (7-19-08)

Our Tradition must always be in accord with Scripture, and cannot contradict it. . . .It is all harmonious with it, and it is all found there in kernel form or more explicitly (material sufficiency of Scripture). It cannot all be found there whole and entire, as the Protestant inconsistently and unrealistically expects. But that is sola Scriptura, which we reject. (1-11-99)

Nevertheless, not every doctrine has to rest solely on Scripture. All doctrines need to be harmonious with, and not contradictory to, Scripture (which is a notion distinct from sola Scriptura). Another way to look at this difference is to realize that when a Protestant uses the terms unbiblical or extrabiblical, he usually means “not found in Scripture.” When Catholics, however, use those terms, we mean “not explicitly in Scripture, yet not contrary to it, and fully consistent with it (as all true doctrines must be).” (Introduction to The Catholic Verses, 2004, p. xvi)

What I was doing there was stating Catholic dogma, which is entirely consistent or harmonious with that passage; not necessarily entirely drawn from it alone, as if every jot and tittle of Catholic ecclesiology is present in 1 Timothy 3:15. Of course it is not. But there is also doctrinal development, and there is a mountain of related scriptural data that we incorporate . . . (3-23-10)

I believe this of all biblical / theological doctrines; therefore purgatory is included.

***

(originally 9-20-11)

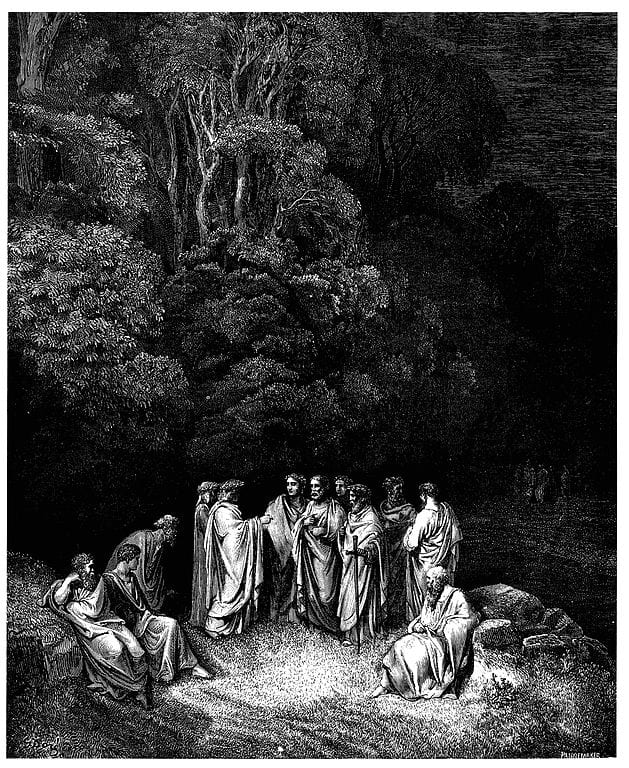

Photo credit: illustration to Dante’s Inferno. Plate XII: Canto IV (1857), by Gustave Doré (1832-1883) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***