A friend of mine commented on my Facebook page (edited slightly for prudential reasons):

Certainly, no blogger / writer / apologist / theologian is going to be everyone’s cup of tea, and it’s good that there is a diversity of views, backgrounds, personalities, etc. If someone is pushing forward a viewpoint that someone else views as heterodox, it seems better to allow them to debate, engage, and discuss their disagreement (so long as it remains civil, charitable, and respectful), than to censor and expel.

Is it so wrong if there are [ostensibly Catholic] writers who hold heterodox views? It seems better to charitably engage and debate such people, than to censor, condemn, and punish them? For some people, ‘heterodox’ means views they disagree with (as opposed to views the Magisterium disagrees with). Too often, it reminds me of the old joke about ‘hate speech’: I’ll tell you what ‘hate speech’ is; it’s speech that I hate!

Heterodoxy is never a good thing, because falsehood is not good, and we know where it ultimately comes from. Dealing with individuals and educating them is one thing (a thing I do all the time). We must be patient and understanding if a person simply doesn’t know (as opposed to deliberate, obstinate falsehood).

Presenting the teaching of Catholicism in public is quite another. Identifiable Catholic writers are responsible to get it right. This is not a matter of mere subjective taste and preference for vanilla ice cream over chocolate, but of objective doctrinal orthodoxy. There is latitude and leeway on some doctrines, such as predestination, or, say, the charismatic movement (which I have defended, as have many popes). But most Catholic doctrines are pretty firmly established by now. So you may ask, “how do we know what is orthodox?” It’s easy:

1) Catechism of the Catholic Church

2) Heinrich Denzinger, Enchiridion Symbolorum: A Compendium of Creeds, Definitions, and Declarations of the Catholic Church

3) Ludwig Ott, Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma (revised and updated 2018 edition)

4) Ecumenical Councils [see a multi-lingual resource containing all the conciliar documents]

5) Papal encyclicals[#1-5 are basically how we determine magisterial Catholic teaching]

6) Good (orthodox!) apologetics and historical materials explaining same if necessary.

I am good friends with the editor and translator of the latest versions of Denzinger and Ott, Dr. Robert Fastiggi.

If we lead people astray by claiming that Catholicism teaches or sanctions doctrine or moral view x, and in fact it does not, God will hold us accountable. Teaching in the Church in any capacity is a very serious business, and James 3:1 (RSV) states: “Let not many of you become teachers, my brethren, for you know that we who teach shall be judged with greater strictness.”

I tremble every day and make sure anything I teach or convey in writing is in accord with the magisterium of the Catholic Church. As far as I know, I have never taught any serious doctrinal error in my 26 years of published Catholic apologetics (Karl Keating recently made note of this: in regarding my overall writings — in terms of orthodoxy — favorably, even compared to Jimmy Akin and Scott Hahn).

I’ve made mistakes, of course (and have publicly retracted and apologized when I did), but nothing of the nature of serious doctrinal dissent or falsehood, as far as I am aware.

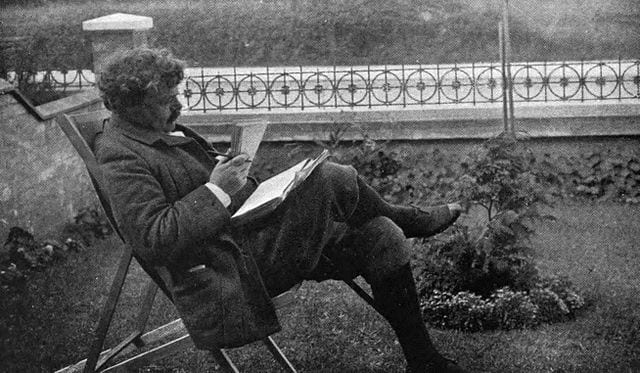

The great apologist G. K. Chesterton wrote eloquently (in his 1908 book, Orthodoxy: written 14 years before he was received into the Catholic Church) about how orthodoxy — far from being a restrictive or negative thing — was wonderfully adventurous and a necessity:

People have fallen into a foolish habit of speaking of orthodoxy as something heavy, humdrum, and safe. There never was anything so perilous or so exciting as orthodoxy. It was sanity: and to be sane is more dramatic than to be mad. It was the equilibrium of a man behind madly rushing horses, seeming to stoop this way and to sway that, yet in every attitude having the grace of statuary and the accuracy of arithmetic. The Church in its early days went fierce and fast with any warhorse; yet it is utterly unhistoric to say that she merely went mad along one idea, like a vulgar fanaticism. She swerved to left and right, so exactly as to avoid enormous obstacles. She left on one hand the huge bulk of Arianism, buttressed by all the worldly powers to make Christianity too worldly. The next instant she was swerving to avoid an orientalism, which would have made it too unworldly. The orthodox Church never took the tame course or accepted the conventions; the orthodox Church was never respectable. It would have been easier to have accepted the earthly power of the Arians. It would have been easy, in the Calvinistic seventeenth century, to fall into the bottomless pit of predestination. It is easy to be a madman: it is easy to be a heretic. It is always easy to let the age have its head; the difficult thing is to keep one’s own. It is always easy to be a modernist; as it is easy to be a snob. To have fallen into any of those open traps of error and exaggeration which fashion after fashion and sect after sect set along the historic path of Christendom–that would indeed have been simple. It is always simple to fall; there are an infinity of angles at which one falls, only one at which one stands. To have fallen into any one of the fads from Gnosticism to Christian Science would indeed have been obvious and tame. But to have avoided them all has been one whirling adventure; and in my vision the heavenly chariot flies thundering through the ages, the dull heresies sprawling and prostrate, the wild truth reeling but erect. (ending of section VI: “The Paradoxes of Christianity”)

Chesterton offers a delightful word-picture of Catholic tradition (my very favorite description of tradition) in the same book:

Catholic doctrine and discipline may be walls; but they are the walls of a playground. Christianity is the only frame which has preserved the pleasure of Paganism. We might fancy some children playing on the flat grassy top of some tall island in the sea. So long as there was a wall round the cliff’s edge they could fling themselves into every frantic game and make the place the noisiest of nurseries. But the walls were knocked down, leaving the naked peril of the precipice. They did not fall over; but when their friends returned to them they were all huddled in terror in the centre of the island; and their song had ceased. (from section IX: “Authority and the Adventurer”)

Conversely, Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman (to be canonized as a saint in the near-future), excoriated the opposite of orthodoxy: the logical reduction of theological liberalism or heterodoxy:

And, I rejoice to say, to one great mischief I have from the first opposed myself. For thirty, forty, fifty years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of Liberalism in religion. Never did Holy Church need champions against it more sorely than now, when, alas! it is an error overspreading, as a snare, the whole earth; and on this great occasion, when it is natural for one who is in my place to look out upon the world, and upon Holy Church as in it, and upon her future, it will not, I hope, be considered out of place, if I renew the protest against it which I have made so often. Liberalism in religion is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another, and this is the teaching which is gaining substance and force daily. It is inconsistent with any recognition of any religion, as true. It teaches that all are to be tolerated, for all are matters of opinion. Revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact, not miraculous; and it is the right of each individual to make it say just what strikes his fancy. Devotion is not necessarily founded on faith. Men may go to Protestant Churches and to Catholic, may get good from both and belong to neither. They may fraternise together in spiritual thoughts and feelings, without having any views at all of doctrines in common, or seeing the need of them. Since, then, religion is so personal a peculiarity and so private a possession, we must of necessity ignore it in the intercourse of man with man. If a man puts on a new religion every morning, what is that to you? It is as impertinent to think about a man’s religion as about his sources of income or his management of his family. Religion is in no sense the bond of society. (“Biglietto Speech” upon becoming a Cardinal, 12 May 1879)

Fifteen years earlier, in his spiritual autobiography, Apologia pro vita Sua, he had noted:

[T]there are but two alternatives, the way to Rome, and the way to Atheism: Anglicanism is the halfway house on the one side, and Liberalism is the halfway house on the other. (chapter 4)

Both Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman and St. Thomas Aquinas taught that if anyone rejects any binding, required doctrine of the Catholic Church, they lose the supernatural virtue of faith. That is downright scary. Servant of God Fr. John A. Hardon, SJ, my mentor, used to reiterate this quite often in his Ignatian catechist classes that I attended.

This is no small matter. To be a Catholic is to accept, obediently in faith, all that the Church infallibly teaches, in her capacity as the Guardian of the apostolic deposit. If someone is picking and choosing what they will accept or reject in infallible Catholic teaching (what has been sarcastically called “cafeteria Catholic”), then they are already functionally or presuppositionally Protestant and have adopted the Protestant, rather than Catholic rule of faith.

We can always grow in our understanding, and better comprehend why we believe what we believe as Catholics (this is the function and purpose of apologetics: my own field, whereas catechetics deals with the “what”). We have an entire lifetime to do that. But in the meantime we believe and adjust our theological beliefs to be in line with those of the Catholic Church (yes, with all her tremendous faults and warts on the part of flawed individuals within her domain), rather than vice versa.

***

Photo credit: G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936), at about the time he wrote Orthodoxy (1908) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***