Unless the apologist creates internal silence in his reader, unless he produces somehow that precious moment of sudden, standstill shock, his apologetics is only chatter or scholarship, not power . . .

Knowing how to create this silence through words is like knowing how to touch a wild animal to quiet it . . .

You need to know and love both the student and the subject, both psychology and theology. Few know both as Pascal does. (p. 36)

336. The reason of effects. We must keep our thought secret, and judge everything by it, while talking like the people.

[Krailsheimer, #91: One must have deeper motives and judge everything accordingly, but go on talking like an ordinary person.]

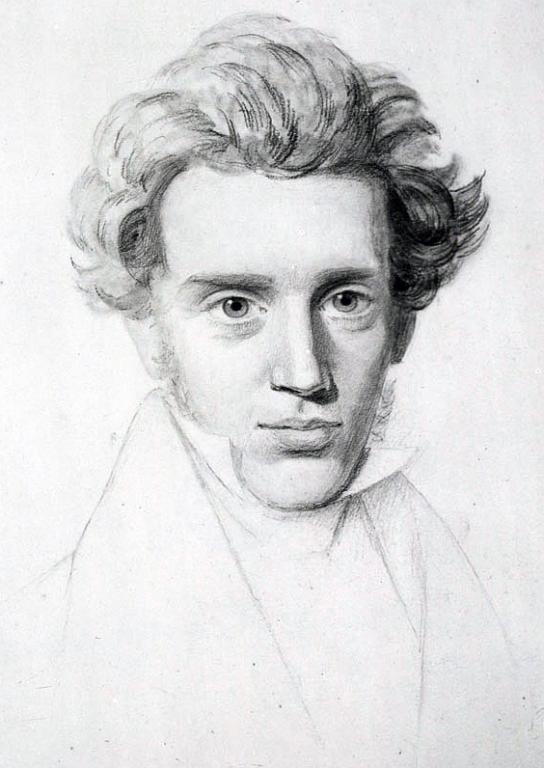

Kierkegaard defined his spy mission this way: to smuggle Christianity back into Christendom (that is, our nominally Christian but really post-Christian society).

Kierkegaard seems to have learned his method, which he calls “indirect communication”, from Pascal. Pascal uses the equivalent of Kierkegaard’s pseudonyms for the same end, namely, to speak from within the opposite point of view, that of alienated, skeptical modern man, rather than speaking only from the passionate, committed point of view of the Christian believer. This is his “cover”. (p. 37)

420. If he exalt himself, I humble him; if he humble himself, I exalt him; and I always contradict him, till he understands that he is an incomprehensible monster.

This is exactly what Jesus did . . . Why did he do this? For Truth. To teach them who they really were: neither angels nor beasts, neither Heavenly nor Hellish, neither sages nor fools, but both . . .

Pascal . . . goes on contradicting us, bothering us, bugging us, until we understand the truth about ourselves. And the truth about ourselves is that we are a mystery, not a problem; a monster, not a puzzle; a living self-contradiction who needs to be contradicted if he is to understand himself.

Like Socrates and Jesus, Pascal does not leave us at rest . . . (pp. 37-38)

9. When we wish to correct with advantage and to show another that he errs, we must notice from what side he views the matter, for on that side it is usually true, and admit that truth to him, but reveal to him the side on which it is false. He is satisfied with that, for he sees that he was not mistaken and that he only failed to see all sides. Now, no one is offended at not seeing everything; but one does not like to be mistaken, and that perhaps arises from the fact that man naturally cannot see everything, and that naturally he cannot err in the side he looks at, since the perceptions of our senses are always true.

Compare what Pascal says here with what Kierkegaard says in The Point of View:

An illusion can never be destroyed directly, and only by indirect means can it be radically removed . . . That is, one must approach from behind the person who is under an illusion . . .A direct attack only strengthens a person in his illusion and at the same time, embitters him. There is nothing that requires such gentle handling as an illusion, if one wishes to dispel it. If anything prompts the perspective captive to set his will in opposition, all is lost . . . This is what is achieved by the indirect method which, loving and serving the truth, arranges everything dialectically for the prospective captive, and then shyly withdraws (for love is always shy), so as not to witness the admission which he makes to himself alone before God — that he has lived hitherto in an illusion.. . . If real success is to attend the effort to bring a man to a definite position, one must first of all take pains to find him where he is and begin there. This is the secret of the art of helping others. . . .

In order to help another effectively I must understand more than he — yet first of all surely I must understand what he understands . . . all true effort to help begins with self-humiliation: the helper must first humble himself under him he would help, and therewith must understand that to help does not mean to be a sovereign but to be a servant, that to help does not mean to be ambitious but to be patient, that to help means to endure for the time being the imputation that one is in the wrong and does not understand what the other understands.

Your prospective captive’s point of view, or world view, is of first importance because it is the hidden premise behind all his arguments.

It is of first importance not only logically but also psychologically, personally. it is more important to the person than what he explicitly says and argues about, because it is the conviction held so close to his heart that he feels he does not need to argue for it, only to assume it.

We find Jesus constantly responding to the other’s point of view rather than to his words: for example, Matthew 19:3-9,16-22; 21:23-27; 22:15-46; John 8:2-11.

What Kierkegaard describes above is also exactly Socrates’ method. Kierkegaard and Pascal apply it to Christianity.

A happy corollary of the last part of this pensee is that everyone sees some truth. Therefore we can learn some truth from every one and every philosophy, even those most disastrously in error . . .

St. Thomas is constantly applying this principle in the Summa. Nearly every answer to every objection takes the form of distinguishing two points of view, or two meanings of a term, and admitting that the objection is right from one point of view (a less adequate one) but wrong from another.

For Aquinas, this consisted mainly in distinguishing two meanings of a term, two logical points of view or horizons of meaning — two different world views. . . .

The apologist must read between the lines and see his opponent’s point of view, for the same reason a general must know the opposing army’s camp and supply lines. In both cases I want to know “where you’re coming from”. For philosophy, unlike science, does not go forward to discover new empirical truths, but backward to illuminate where arguments come from. Science builds skyscrapers, philosophy inspects foundations. (pp. 39-42)

10. People are generally better persuaded [Krailsheimer: “convinced more easily”] by the reasons which they have themselves discovered than by those which have come into the mind of others.

Therefore it is a more effective apologetic strategy to get your opponent to discover the truth for himself than for you to give it to him . . . How is this to be done? We have just seen Pascal’s answer: indirect communication, spying, looking at things from your opponent’s point of view and drawing out the consequences of his premises. In other words, the Socratic method. (p. 42)

***

(originally 9-2-05)

Photo credit: portrait of Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), c. 1840 [public domain / Wikipedia]

***