[A]lthough I tire of making every discussion about authority, I’m not sure you can talk about development without talking about authority. I recently read a very nice scholarly book (by N. T. Wright) in which “developing” a theological doctrine was consistently contrasted with “deviating” from the earlier doctrine. And yet Wright did not (at least in that work) tell us how to distinguish between the two. I’m afraid that, with no neutral place to make such judgments, authority of some sort may sneak back in as the way to distinguish “development” from “deviation.” Again, this is as true (potentially) for Protestants as for RCs.

My own attempt to make a more careful, specific, and debatable claim about development would be this: Both Protestants and Catholics affirm things doctrinally, even in official church settings, that would not have been dreamed of by the first-century Christians (my field of study).

I agree. But (here is my own explanation of that) they wouldn’t have been because Christians in those times were far too early to have understood the more complex reflections that came about due to centuries of reflection. No first or second century Christian could have grasped the complicated Chalcedonian Christology and trinitarianism (even many Christians who lived in that period failed to accept or grasp it: the Monophysites and Nestorians, etc., and later the Monothelites).

Yet the doctrines of the Holy Trinity or the Deity of Christ are no innovations (as I assume you would agree). So I must dissent from what you say here, that we are talking about innovations rather than developments.

or by the first 2d / 3d century Christians (Edwin’s field of study).

To a lesser extent than in the post-apostolic age, but yes, it was still a relatively early stage. Plus, one figures that (from a Protestant perspective) it also took 15 centuries to grasp supposedly elementary and altogether biblically perspicuous claims such as sola fide and sola Scriptura. :-) :-)

I know of no fair reason not to call these doctrines innovations.

I just gave one (I think) rather obvious example to the contrary. I could provide many more, but that would involve getting into particulars. I think the only way to properly resolve this dispute is to either:

1) laboriously go over the principles of development and how they are arrived at (Edwin and I started that years ago but it was never resolved one way or the other, including my recent exchanges with him);

or,

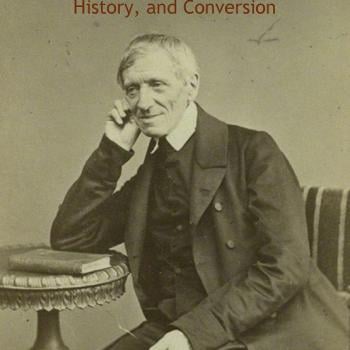

2) to examine some individual doctrine and to discuss what elements were legitimate developments of it and which were corruptions. Newman does both in his Essay on Development.

If you would be willing to engage in either discussion, nothing (in terms of interaction with opposing ideas) would interest me more, as development has long been my favorite theological topic (and of course it was key in my own conversion).

I know of no neutral ground for determining which of these innovations are “in continuity” or “developments” of earlier doctrines–much less of determining which ones are “infallible.”

That requires one of the two huge discussions I mentioned above to determine pro or con. I don’t see how you can contend this, given the actual course Christian theology has taken, even considering only the doctrines that we all hold in common.

Certainly the official RC line is that the official RC line is correct. (Surprise, surprise!)

This has nothing to do with that anymore than Newman’s Essay did. He wrote it while still an Anglican. This is about serious consideration of particular Christian doctrines and what is or isn’t consistent with them: something which has always been done by all kinds of Christians without necessary consideration of development.

Secondly, it is an historical question which can be verified or falsified by historical fact (inasmuch as we can ascertain same, within historiographical guidelines for determining historical “fact”), just as any other historical dispute proceeds.

But the average RC (in my experience) seems to think that his own church is mostly right most of the time, just as I think mine is mostly right most of the time, in a humbler fashion.

*

Of course, but again, none of that is required here. I rarely appeal merely to Catholic Church authority in my apologetics. I appeal to historical fact, reason, and the Bible. At the end of that inquiry, of course I might state that this is what the Catholic Church teaches, and that it has just been supported by the above three elements of proof and evidence, but the authority itself formed no part of my actual apologetic argument.

What is your church, by the way?

Thanks for your comments, and let me know if you want to do a serious discussion on one or more of the very important questions that you raised.

Hey, Dave. Thanks. You’ve pretty much cleared up for me what you’re discussing and why. I’m not sure how much I’d agree with or not, but much of it isn’t my area of interest enough for me to have done the “homework” necessary for the discussion. (By the way, I wasn’t assuming that an “innovation” was invalid; I wasn’t opposing it to “development.”)

As to my own “church”–well, I belong to the only church there is (as, I trust, do you). But my own “chunk” of it is called the Christian Churches (Restoration Movement). We are an “ad fontes” group who are slightly uncomfortable with leaning too heavily on doctrinal reflections that the first-century Christians “could not have grasped.” So development is less important to me than to you.

My question is always–if I believe, and teach, the doctrinal content that Paul’s churches believed and taught, why isn’t that enough?

Of course it is enough. The Bible is materially sufficient for doctrine and salvation. I believe that as a Catholic. I deny, however, that it is formally sufficient as a rule of faith, which is a different question altogether, involving the role and place and relative authority of Church and Tradition as well as Scripture.

I’m not saying that everything subsequent–from Chalcedonian Trinitarianism (with which I think I agree) to Catholic doctrines of the papacy(with which I think I disagree)–is a corruption. But surely it is most important, and even sufficient, to believe/teach things that Paul COULD have grasped.

I don’t disagree. Everything was present in the apostles (what we call the “apostolic deposit”) that was later developed by theologians and saints. The essentials or “kernels” were there, from which later orthodox reflection derived. We simply understand some things more deeply with the reflection of centuries. Theology is not a static enterprise.

As for St. Paul himself, it is not necessarily the case that he wouldn’t have been able to grasp the Chalcedonian theology of God. He happened to have been philosophically trained and I think he would have readily understood it if it had been explained to him by a hypothetical visitor from the 5th century.

On the other hand, he may have simply never have thought of such things as were discussed 400 years later (just as many Fathers previous to that did not, if their lack of treating certain topics is any indication). That is no reflection (negatively) on him, anymore than a lack of understanding of Einstein’s relativity by Isaac Newton diminishes the latter’s import and profound influence on later physics and astronomy.

It’s also true that St. Paul, being an apostle, and an instrument of divine inspiration when he wrote Scripture, may have likely understood a far more complex theology, but simplified it in his writing because of the purpose of the New Testament and the capacity of the great bulk of those who would read it through the centuries.

Fascinating to ponder . . .

Restoring first-century doctrines is, I know, a debatable project. But the project is (in its own way) interesting and (I think) a more solid basis for truth and unity than choosing between competing doctrines neither of which 1st-century Christians could have understood. So I’m a Biblical scholar more than a historical theologian.

Thanks for the discussion. Have fun.

***

(originally posted on 11-12-05)

Photo credit: St. John Henry Cardinal Newman [public domain]

***