An anti-Catholic Protestant blog called Evangelical Miscellanies produced a lengthy article entitled, “Was the Bible Forbidden by the Roman Church?” (5-10-21). Presently, I shall be dealing with portions (in blue below) having to do with the ecumenical Council of Trent (1545-1563).

The Catholic Church opposed what it considered bad translations, not the Bible itself, and it was open to the idea of vernacular translations (which I dealt with in both my first reply and my second), as well as the Hebrew and Greek manuscripts (not just the Latin ones). The concern of Holy Mother Church was to preserve the authentic inspired revelation of the Bible, rather than distortions of men, that were inaccurate. Obviously, the is a pro-Bible attitude, not an anti-Bible outlook. All bolding throughout will be my own.

Council of Trent (1563 A.D.):

Session XXV, Ten Rules Concerning Prohibited Books Drawn Up by The Fathers Chosen by the Council of Trent and Approved by Pope Pius:

III:

The translations of writers, also ecclesiastical, which have till now been edited by condemned authors, are permitted provided they contain nothing contrary to sound doctrine. Translations of the books of the Old Testament may in the judgment of the bishop be permitted to learned and pious men only, provided such translations are used only as elucidations of the Vulgate Edition for the understanding of the Holy Scriptures and not as the sound text. Translations of the New Testament made by authors of the first class of this list shall be permitted to no one, since great danger and little usefulness usually results to readers from their perusal. . . .

(Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent: Original Text With English Translation, trans. H. J. Schroeder, O.P., [B. Herder Book Company, 1960], p. 274). Ecclesiastical approbation: [“Nihil Obstat,” Fr. Humbertus Kane, O.P., Fr. Alexius Driscoll, O.P., “Imprimi Potest,” Fr. Petrus O’Brien, O.P., Prior Provincialis, “Nihil Obstat,” Sti. Ludovici, die 5, Septembris, 1941, A.A. Esswin, Censor Deputatus, “Imprimatur,” Sti. Ludovici, die 5, Septembris, 1941, Joannes J. Glennon, Archiepiscopus]. Here

Readers may want to know what sections I and II stated, too:

I

All books which have been condemned either by the supreme pontiffs or by ecumenical councils before the year 1515 and are not contained in this list, shall be considered condemned in the same manner as they were formerly condemned.

II

The books of those heresiarchs, who after the aforesaid year originated or revived heresies, as well as of those who are or have been the heads or leaders of heretics, as Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, Balthasar Friedberg, Schwenkfeld, and others like these, whatever may be their name, title or nature of their heresy, are absolutely forbidden. The books of other heretics, however, which deal professedly with religion are absolutely condemned. Those on the other hand, which do not deal with religion and have by order of the bishops and inquisitors been examined by Catholic theologians and approved by them, are permitted. Likewise, Catholic books written by those who afterward fell into heresy, as well as by those who after their fall returned to the bosom of the Church, may be permitted if they have been approved by the theological faculty of a Catholic university or by the general inquisition.

In summary so far: Bible translations from heretics are mostly prohibited; their translations of other texts requires ecclesiastical approval.

IV:

Since it is clear from experience that if the Sacred Books are permitted everywhere and without discrimination in the vernacular, there will by reason of the boldness of men arise therefrom more harm than good, the matter is in this respect left to the judgment of the bishop or inquisitor, who may with the advice of the pastor or confessor permit the reading of the Sacred Books translated into the vernacular by Catholic authors to those who they know will derive from such reading no harm but rather an increase of faith and piety, which permission they must have in writing. Those, however, who presume to read or possess them without such permission may not receive absolution from their sins till they have handed them over to the ordinary. . . .

(Ibid., [B. Herder Book Company, 1960], pp. 274-275 . . . ) Here

The Catholic Church simply wanted to check out and approve vernacular translations of the Bible. What in the world is wrong with that? It’s no different from Protestants being concerned to read a translation that is accurate and true to the original Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. In section VI (cited in the article), it was stated also that theological writings in the vernacular languages require Church approval. None of this is anti-Bible at all. Robert E. McNally, SJ, sums it up:

While it is true that the Council did not explicitly approve of translations of the Bible in the language of the people, it is equally true that it did not condemn the preparation and dissemination of such popular versions. (“The Council of Trent and Vernacular Bibles”, pp. 225-226)

At length, the Church would be much more “open and tolerant” about such matters (especially after Vatican II), but in the supercharged, tense aftermath of the initial explosion of the Protestant Revolt, it decided to take a fairly reactionary stance (just as the new Protestant denominations very quickly became reactionary and quite hostile with regard to each other). This was not understood from the Catholic perspective as “anti-Bible”; but rather, “pro-Vulgate as the ‘authorized’ and preeminent translation and model for vernacular translations.”

This is little different in the main from the strong allegiance of many Protestants to the King James Version of 1611. It’s not “anti-Bible” to favor that version, nor is it “anti-Bible” for the Catholic Church to strongly prefer its “standard”: the Latin Vulgate of St. Jerome and other approved versions drawn and inspired by it. Ecclesiastically approved vernacular versions had been encouraged and accepted all along.

Catholic writer Barrett Turner made further interesting and helpful analysis of Trent and the Bible:

According to [John] Calvin, Trent swept away the need for studying Greek and Hebrew in marking the Vulgate as the authentic text of the Church. Yet Calvin has read more into the decree [on the Bible, from 1546] than the decree says. Calvin, a man with a great talent for sober and elegant writing and interpretation, here gave way to impassioned “eisegesis” of what Trent really said. Trent nowhere forbids the use of the original languages, as if St. Jerome had not used them to revise the Old Latin texts or make his own translations. One may add here that certain Reformers were perhaps overly optimistic about their Hebrew text or even about the manuscripts of the New Testament which they currently had in their possession. Modern biblical scholarship, especially after the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, has deemed various Greek translations of the Old Testament to more accurately preserve the Hebrew Vorlage than the Masoretic text in some books. Further, the New Testament text used by early Protestant translators as the basis for the Geneva and the King James Bibles, the so-called textus receptus, no longer has priority in critical editions of the New Testament, such as Nestle-Aland’s Novum Testamentum Graece. Modern vernacular Bibles therefore no longer use the textus receptus as their base text. . . .

The problem was not the use of Greek and Hebrew by the Reformers, as embarrassing as that was for some Catholic polemical authors. After all, scholars who remained within the Catholic Church had begun to use the original languages before Protestants started openly defying the Church’s leadership and traditions. One need look no further than the Complutensian Polyglot (1516), completed in Alcala, Spain, under Cardinal Ximenes, who dedicated the work to Pope Leo X, or the Greek edition of the New Testament edited by Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536). Such scholars desired to see greater familiarity with Sacred Scripture and were no less ardent in calling for the reform of abuses than were Protestants. . . .

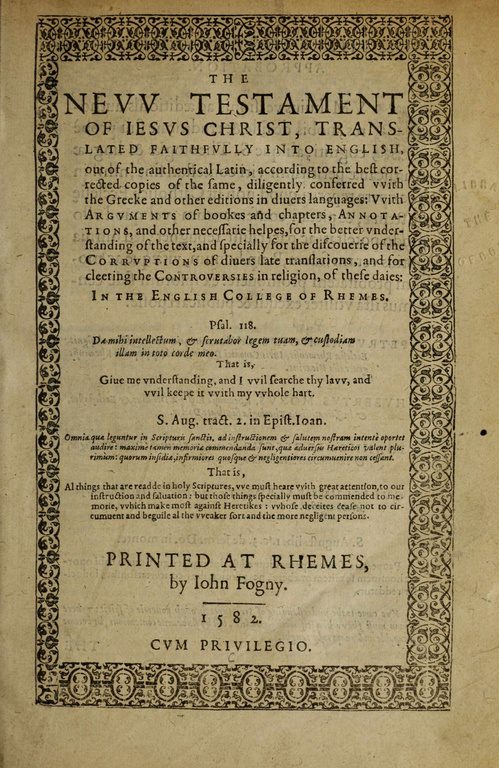

The reluctance of the Council to ban translations of the Bible into vernacular languages opened the door for translations such as the Reims New Testament (1582) and the entire Douai-Reims Bible (1609-1610). . . .

[T]he council provides a way to achieve this reform in decreeing that a “thorough revision” of the Latin Bible is to be made. The council does not deny what everyone already knew, namely, that the text of the Vulgate had been corrupted in places by transmission errors. Enshrining the Vulgate as the “authentic” edition does not mean that the Vulgate cannot be revised in light of the best Latin manuscripts or that one may never correct the Latin text using the Hebrew or Greek manuscript traditions. In this openness to humanistic textual criticism, the Tridentine Fathers order that the Vulgate be corrected after the Council such that one version attaining as closely as possible to Jerome’s original translation would find universal use. The employment of Greek and Hebrew to correct the Latin was not forbidden in any way. The revision of the Vulgate was completed under popes Sixtus V and Clement the VIII and published in 1598. (“Calvin, Trent, and the Vulgate: Misinterpreting the Fourth Session”, Called to Communion, 6-13-11)

Now I should like to “turn the tables” and offer an argument by analogy and a challenge. I have shown now, over three articles, that the Catholic Church was (and is not) opposed to the Bible; only to (from its perspective) bad translations of it. My analogical example is concerned with precisely the same thing, but it comes from an an English Puritan divine, William Fulke (1538-1589). He wrote a polemical work, A Defense of the Sincere and True Translations of the Holy Scriptures into the English tongue, against the Manifold Cavils, Frivolous Quarrels, and Impudent Slanders of Gregory Martin (1583).

This was a frontal attack on the Catholic Rheims New Testament (English), that had been produced the year before. Fulke didn’t “rejoice” that another Bible translation was available. Rather, he gave it everything he had in opposing it. See the parallel? Catholics opposed Protestant versions, and vice versa, while both saw themselves as championing the true, authentic Bible. It’s exactly the same in that respect.

The Rheims New Testament and the King James Version (KJV) — despite the tragic divisions following the Protestant Revolt — have an interesting “dual” history. As I wrote in the Introduction to my own Bible “selection”, the Victorian King James Version:

The New Testament portion [of the KJV] was also stylistically influenced to a considerable extent by the Catholic Rheims New Testament, with the demonstrable adoption even of many of the former’s extensive and colorful “Latinate” words. . . .

The Rheims New Testament (1582), like all Catholic versions until the 20th century, was a translation of St. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate from the 5th century, though primary translator Gregory Martin “conferred” with Greek manuscripts as well, and his version shows particular awareness of subtle distinctions in the Greek past tense; moreover, [F. F.] Bruce noted [History of the Bible in English, Oxford University Press, 3rd edition, 1978, pp. 122-123] that its treatment of the Greek definite article was “more accurate” than that of the KJV. It also was influenced by the Protestant Tyndale translation and the earlier Wycliffe Bible.

It was greatly revised by Bishop Richard Challoner in 1750; drawing considerably from KJV style, as his “base text.” The result was a revised version – geared towards greater readability – that bore more similarity to the KJV than its own heavily “latinate” predecessor. Bruce describes a “profound influence . . . even more in the cadences of the language than in the vocabulary” (p. 125).

But back to William Fulke. He saw no value or usefulness at all in the Rheims version, and was not one to mince words:

I shall have occasion also to shew, that the papists themselves of our times, maintaining their corrupt vulgar translation against the truth of the original texts of Greek and Hebrew, are most guilty of such corruption and falsification; whereof although they be not the first authors, yet, by obstinate defending of such errors, they may prove worse than they which did first commit them. For the authors of that vulgar translation might be deceived, either for lack of exact knowledge of the tongues, or by some corrupt and untrue copies which they followed, or else perhaps that which they had rightly translated, by fault of the writers and negligence of the times might be perverted : but these men frowardly justifying all errors of that translation, howsoever they have been brought in, do give plain testimony, that they are not led with any conscience of God’s truth, but wilfully carried with purpose of maintaining their own errors; lest, if they did acknowledge the error of the Romish church in that one point, they should not be able to defend any one iota of their heresy, whose chief colour is the credit and authority of that particular and false church, rather than any reason or argument out of the holy scriptures, or testimony of the most ancient christian and catholic church. (Answer to the Preface, p. 13)

[W]hereas we have translated idololatria, Col. iii. ” worshipping of images,” we have done rightly ; and your Latin interpreter will warrant that translation, which translateth the same word, simulacrorum servitus, the service of images. It is you therefore, and not we, that are to be blamed for translation of that word; for where you charge us to depart from the Greek text, which we profess to translate, we do not, except your vulgar translation be false. But you, professing to follow the Latin, as the only true and authentical text, do manifestly depart from it in your translation ; for the Latin being simulacrorum servitus, you call it the service of idols, appealing to the Greek word, which you have set in the margin, . . . and dare not translate according to your own Latin; for then you should have called covetousness even as we do, the worshipping or service of images. And yet you charge us in your notes with a marvellous impudent and foolish corruption. (p. 106)

The word priest, by popish abuse, is commonly Fulke,10. taken for a sacrificer, the same that sacerdos in Latin. But the Holy Ghost never calleth the ministers of the word and sacraments of the New Testament . . . sacerdotes. Therefore the translators, to make a difference between the ministers of the Old Testament and them of the New, calleth the one, according to the usual acception, priests, and the other, according to the original derivation, elders. Which distinction seeing the vulgar Latin text doth always rightly observe, it is in favour of your heretical sacrificing priesthood, that you corruptly translate sacerdos and presbyter always, as though they were all one, a priest, as though the Holy Ghost had made that distinction in vain, or that there were no difference between the priesthood of the New Testament and the Old. The name of priest, according to the original derivation from presbyter, we do not refuse: but according to the common acception for a sacrificer, we cannot take it, when it is spoken of the ministry of the New Testament. And although many of the ancient fathers have abusively confounded the terms of sacerdos and presbyter, yet that is no warrant for us to translate the scripture, and to confound that which we see manifestly the Spirit of God hath distinguished. (p. 109)

Well, folks, both parties were doing precisely the same thing (though, I would say, with differing strength of argument and plausibility): categorizing theological opponents as heretics, based on what is believed to be inaccurate translations flowing from a prior (heretical) theological bias. And this is but one example of countless ones that could be brought forth.

Therefore, the Protestant who objects to Tridentine decrees regarding “bad” Bible translations as supposedly “anti-Bible” must (in logical consistency) object in the same manner to efforts such as Fulke’s (or indeed any serious criticism of any Bible translation), if he or she is to be objective about it.

In other words, the objection collapses since Protestantism’s own methodology in opposing Catholicism (i.e., objections to Catholic Bible versions) is the exact equivalent of the converse (Catholics opposing Protestant translations). To put it another way, if a Protestant is to object to the very existence of other translations (as Fulkes did), then he or she can’t immediately dismiss Catholics doing the same thing from the opposite direction. Goose and gander . . .

Principled objections to various translations — from all kinds of different perspectives — still exist today, as always. I’ve done it myself: having criticized the NIV for bias against sacred tradition and bias in favor of divorce. Thankfully, there is a broad Christian agreement on the desirability of accurate and readable translations, and these sorts of fights are mostly a thing of the past. Misrepresenting the positions of other Christians does no one any good.

***

Photo credit: title page of the Catholic translation of the New Testament into English (Gregory Martin et al), published at Rheims, France in 1582, and vigorously opposed by Protestant anti-Catholic polemicists such as William Fulke. [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: I contend that the Council of Trent, like the Catholic Church, is “anti-bad Bible translations”, rather than “anti-Bible.” I show how Protestants argue in precisely the same way, too.