Michael J. Alter is the author of the copiously researched, 913-page volume, The Resurrection: a Critical Inquiry (2015). I initially offered 59 “brief” replies to as many alleged New Testament contradictions (March 2021). We later engaged in amiable correspondence and decided to enter into a major ongoing dialogue about his book. He graciously (and impressively!) sent me a PDF file of it, free of charge, for my review.

Mike describes himself as “of the Jewish faith” but is quick to point out that labels are often “misleading” and “divisive” (I agree to a large extent). He continues to be influenced by, for example, “Reformed, Conservative, Orthodox, and Chabad” variants of Judaism and learns “from those of other faiths, the secular, the non-theists, etc.” Fair enough. I have a great many influences, too, am very ecumenical, and am a great admirer of Judaism, as I told Michael in a combox comment on my blog.

He says his book “can be described as Jewish apologetics” and one that provides reasons for “why members of the Jewish community should not convert to Christianity.” I will be writing many critiques of the book and we’ll be engaging in ongoing discussion for likely a long time. I’m quite excited about it and am most grateful for Mike’s willingness to interact, minus any personal hostility.

To see all the other installments, search “Michael J. Alter” on either my Jews and Judaism or Trinitarianism & Christology web pages. That will take you to the subsection with the series.

I use RSV for all Bible verses that I cite. His words will be in blue.

*****

Alter wrote:

CONTRADICTION #85 Acts Contradicts Matthew—Judas’s Repentance

The account of Judas’s nonrepentance reported in Acts directly contradicts Matthew. This narration is perhaps one of the simplest and yet strongest arguments supporting the thesis that their respective authors wrote completely different stories. Unequivocally, these two stories demonstrate no resemblance to each other. . . .

Matthew 27:3-5 reports that after Jesus was arrested: “Then Judas, which had betrayed him, when he saw that he was condemned, repented himself, and brought again the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and elders, Saying, I have sinned in that I have betrayed the innocent blood. And they said, What is that to us? see thou to that. And he cast down the pieces of silver in the temple, and departed, and went and hanged himself.” . . . Judas repented (i.e., felt remorseful) . . . A careful analysis of Matthew’s Judas reveals a repentant and remorseful Judas. . . . Judas was so remorseful that he wanted nothing to do with the money that he had received for betraying Jesus. . . .

Contrary to Matthew, in Acts there is no repentance, no remorse, and no sense of guilt. (pp. 503-504, 507)

In Matthew 27:3-4, it says in RSV that Judas “repented” and said “I have sinned in betraying innocent blood.” Acts 1:16-20, in mentioning Judas’ suicide, simply doesn’t say one way or the other whether he repented or not. So it’s an argument from silence, from which nothing can be determined, as to alleged contradiction. But there is also a linguistic consideration (the following sources are all commenting on Matthew 27:3):

The Greek word is not that commonly used for “repentance,” as involving a change of mind and heart, but is rather “regret,” a simple change of feeling. (Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers)

A different Greek word from that used, ch. Matthew 3:2; it implies no change of heart or life, but merely remorse or regret. See note ch. Matthew 21:29; Matthew 21:32. (Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges)

Repented himself (μεταμεληθείς). This word (differing from μετανοέω, which expresses change of heart) denotes only a change of feeling, a desire that what has been done could be undone; this is not repentance in the Scripture sense; it springs not from love of God, it has not that character which calls for pardon. (Pulpit Commentary)

Repented himself (μεταμελητεις — metamelētheis). Probably Judas saw Jesus led away to Pilate and thus knew that the condemnation had taken place. This verb (first aorist passive participle of μεταμελομαι — metamelomai) really means to be sorry afterwards like the English word repent from the Latin repoenitet, to have pain again or afterwards. See the same verb μεταμελητεις — metamelētheis in Matthew 21:30 of the boy who became sorry and changed to obedience. The word does not have an evil sense in itself. Paul uses it of his sorrow for his sharp letter to the Corinthians, a sorrow that ceased when good came of the letter (2 Corinthians 7:8). But mere sorrow avails nothing unless it leads to change of mind and life (μετανοια — metanoia), the sorrow according to God (2 Corinthians 7:9). This sorrow Peter had when he wept bitterly. It led Peter back to Christ. But Judas had only remorse that led to suicide. (A. T. Robertson, Word Pictures in the New Testament)

Repented ( μεταμεληθεὶς )

This is a different word from that in Matthew 3:2; Matthew 4:17; μετανοεῖτε , Repent ye. Though it is fairly claimed that the word here implies all that is implied in the other word, the New Testament writers evidently recognize a distinction, since the noun which corresponds to the verb in this passage ( μεταμέλεια ) is not used at all in the New Testament, and the verb itself only five times; and, in every case except the two in this passage (see Matthew 21:32), with a meaning quite foreign to repentance in the ordinary gospel sense. Thus it is used of Judas, when he brought back the thirty pieces (Matthew 27:3); of Paul’s not regretting his letter to the Corinthians (2 Corinthians 7:8); and of God (Hebrews 7:21). On the other hand, μετανοέω , repent, used by John and Jesus in their summons to repentance (Matthew 3:2; Matthew 4:17), occurs thirty-four times, and the noun μετάνοια , repentance (Matthew 3:8, Matthew 3:11), twenty-four times, and in every case with reference to that change of heart and life wrought by the Spirit of God, to which remission of sins and salvation are promised. It is not impossible, therefore, that the word in this passage may have been intended to carry a different shade of meaning, now lost to us. Μεταμέλομαι , as its etymology indicates ( μετά , after, and μέλω , to be an object of care), implies an after-care, as contrasted with the change of mind denoted by μετάνοια . Not sorrow for moral obliquity and sin against God, but annoyance at the consequences of an act or course of acts, and chagrin at not having known better. “It may be simply what our fathers were wont to call hadiwist (had-I-wist, or known better, I should have acted otherwise)” (Trench). Μεταμέλεια refers chiefly to single acts; μετάνοια denotes the repentance which affects the whole life. Hence the latter is often found in the imperative: Repent ye (Matthew 3:2; Matthew 4:17; Acts 2:38; Acts 3:19); the former never. Paul’s recognition of the distinction (2 Corinthians 7:10) is noteworthy. “Godly sorrow worketh repentance ( μετάνοιαν ) unto salvation,” a salvation or repentance “which bringeth no regret on thinking of it afterwards” ( ἀμεταμέλητον )There is no occasion for one ever to think better of either his repentance or the salvation in which it issued. (Marvin Vincent, Word Studies in the New Testament)

2 Corinthians 7:9-10 As it is, I rejoice, not because you were grieved, but because you were grieved into repenting; for you felt a godly grief, so that you suffered no loss through us. [10] For godly grief produces a repentance that leads to salvation and brings no regret, but worldly grief produces death.

Nathan Millican from the Theology Along the Way website, commented insightfully on Judas and this issue of his repentance (or lack thereof):

A worldly sorrow brings regret that leads to death, whereas a godly sorrow does not bring regret and leads to salvation. Barnett in his Second Corinthians Commentary writes, “the structure of Paul’s verse is: For the grief that is according to God works repentance [that] leads to salvation, [which] is without regret. But the grief that is of the world works death.”[1] Thus, there is a truth inferred here that is important for the discussion at hand, which is the “grief that is of the world works [unrepentance, which leads to] death [and is with regret].”[2] . . .

This type of sorrow as evidenced in Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians is not a sorrow that leads to salvation, but rather brings with it death. Judas regretted his actions or showed remorse or sorrow for his actions because of their consequences “not necessarily because they were wrong as sins against a holy God.”[5] What did Judas lack? He lacked a godly sorrow that brings no regrets that leads to salvation. His remorse was not commensurate with a remorse that God says is a prerequisite to salvation. And what was the end result of his remorse? He ended his life. “He was sorry for his sin, but instead of taking his sorrow to God, he despaired. He turned inward, not Godward, and his remorse became self-condemnation.”[6] (“Why wasn’t Judas’ repentance a repentance that leads to eternal life?”)

“A Tragic End for Judas” (Ligonier Ministries) adds:

Matthew’s juxtaposition of Peter’s denial and Judas’ death invites us to compare the state of their souls. Like Peter, Judas is remorseful after the fact, changing his mind about the wisdom of his deed after seeing Jesus condemned (Matt. 27:3–4). . . . Judas does not really try to stop what he has started and will not testify of Christ’s innocence before Pilate. John Calvin writes, “True repentance is displeasure at sin, arising out of fear and reverence for God, and producing, at the same time, a love and desire of righteousness.” Were Judas repentant, justice and righteousness would move him to intervene on Jesus’ behalf. Godly sorrow leads people to run to God, but Judas’ despair makes him run into the arms of death (v. 5).

Since Acts mentions no repentance or even remorse at all, and the remorse felt by Judas as described in Matthew 27:3 is by no means the normative New Testament repentance with grace-enabled profound reform of one’s life and joy accompanying, the alleged contradiction is refuted. Judas didn’t “repent” in the full NT sense in either passage.

***

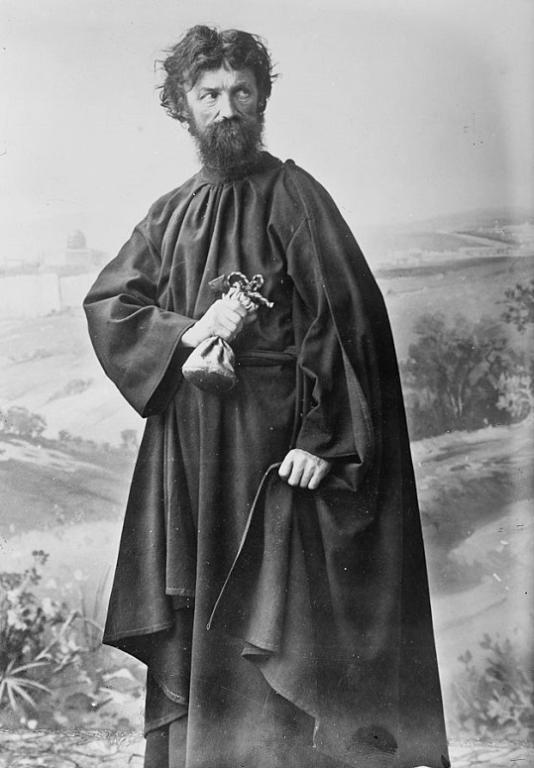

Photo credit: Judas (Johann Zwink) in passion play, Oberammergau, Germany (1900) [public domain / Library of Congress]

Summary: Michael Alter, dealing with the question of “did Judas repent or not?” tries to argue that Matthew records a true repentance, while Acts does not at all (hence, a contradiction: so he claims).

Tags: alleged Bible contradictions, alleged Resurrection contradictions, Bible “contradictions”, Bible “difficulties”, Bible Only, biblical inspiration, biblical prooftexts, biblical skeptics, biblical theology, exegesis, hermeneutics, Holy Bible, inerrancy, infallibility, Jewish anti-Christian polemics, Jewish apologetics, Jewish critique of Christianity, Jewish-Christian discussion, Michael J. Alter, New Testament, New Testament critics, New Testament skepticism, Resurrection “Contradictions”, Resurrection of Jesus, The Resurrection: A Critical Inquiry, Judas, motives of Judas, Judas’ repentance, repentance of Judas, did Judas repent?