Lucas Banzoli is a very active Brazilian anti-Catholic polemicist, who holds to basically a Seventh-Day Adventist theology, whereby there is no such thing as a soul that consciously exists outside of a body, and no hell (soul sleep and annihilationism). This leads him to a Christology which is deficient and heterodox in terms of Christ’s human nature after His death. He has a Master’s degree in theology, a degree and postgraduate work in history, a license in letters, and is a history teacher, author of 25 books, as well as blogmaster (but now inactive) for six blogs. He’s active on YouTube.

***

The words of Lucas Banzoli will be in blue. I used Google Translate to transfer his Portugese text into English.

*****

Part One: “Disproofs” #1-50

See other installments:

Part Three: “Disproofs” #101-15o

Part Four: “Disproofs” #151-205

*****

I am responding to his article, “205 Provas Contra O Primado de Pedro” (no date) [205 Proofs Against the Primacy of Peter]. It’s a reply to my well-known article, 50 New Testament Proofs for Petrine Primacy & the Papacy, which was written in 1994 as part of my first book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism: completed in May 1996 but not “officially” published until 2003 (Sophia Institute Press). The article has been posted on my website since it began in February 1997, and was also published in the print magazine, The Catholic Answer, Jan/Feb 1997, 32-35 (now posted at the Catholic Culture site). It was translated into Portugese in the late 1990s by Carlos Martins Nabeto and also by Ewerton Wagner Santos Caetano sometime before July 2008. Apparently, it has been widely spread in Brazil for some time now.

Protestant anti-Catholic apologist Jason Engwer made similar critiques of the article, which I comprehensively responded to:

“Reply to Critique of “50 NT Proofs for the Papacy,” (vs. Jason Engwer) [3-14-02]

Refutation of a Satirical “Pauline Papacy” Argument (vs. Jason Engwer) [9-30-03]

St. Peter Listed First in Lists of Disciples: A Debate (vs. Jason Engwer) [10-12-20]

It should be made clear at the outset, exactly what I think my article established; how much I claim for it (since Lucas seems to take a low view of cumulative arguments). I wrote in the initial article itself:

The Catholic doctrine of the papacy is biblically based, and is derived from the evident primacy of St. Peter among the apostles. Like all Christian doctrines, it has undergone development through the centuries, but it hasn’t departed from the essential components already existing in the leadership and prerogatives of St. Peter. . . . The biblical Petrine data is quite strong and convincing, by virtue of its cumulative weight, . . .

In conclusion, it strains credulity to think that God would present St. Peter with such prominence in the Bible, without some meaning and import for later Christian history; in particular, Church government. The papacy is the most plausible (we believe actual) fulfillment of this.

In my 2002 reply to Engwer I vigorously defended the article:

I think it is very strong, certainly stronger than the biblical cases for sola Scriptura and the canon of the New Testament (which are nonexistent). . . .

As I said, it is a “cumulative” argument. One doesn’t expect that all individual pieces of such an argument are “airtight” or conclusive in and of themselves, in isolation, by the nature of the case. . . . Obviously, passages like the two above [Jn 20:67 and Acts 12:5] wouldn’t “logically lead to a papacy.” But they can quite plausibly be regarded as consistent with such a notion, as part of a demonstrable larger pattern, within which they do carry some force. . . . Another way to respond to this would be to make an analogy to a doctrine that Jason does accept: the Holy Trinity:

Does Jason really think it’s reasonable to expect me to explain to him why passages like Isaiah 9:6 and Zechariah 12:10 don’t logically lead to Chalcedonian trinitarianism and the Two Natures of Christ?

Obviously, the Jews are quite familiar with Isaiah 9:6 and Zechariah 12:10, but they don’t see any indication of trinitarianism at all in them, nor do the three passages above “logically lead” to trinitarianism, if they are not interconnected with many, many other biblical evidences. Yet they are used as proof texts by Christians. No one claims that they are compelling by themselves; these sorts of “proofs” are used in the same way that my lesser Petrine evidences are used, as consistent with lots of other biblical data suggesting that conclusion. . . . Likewise, with many Protestants and the papacy and its biblical evidences. . . .

[O]ne strong Protestant presupposition is that Paul was much more important than Peter. Indeed, that is how it appears on the face of it in the New Testament (with so many books written by Paul and all). As with many Catholic beliefs, one must take a deeper look at Scripture to see how the pieces of Catholicism fit together in a harmonious whole.

Knowing this, I approached the Petrine list with the thought in mind: “Paul is obviously an important figure, but how much biblical material can one find with regard to Peter, which would be consistent with (not absolute proof of) a view that he was the head of the Church and the first pope?” Or, to put it another way (from the perspective of preexisting Catholic belief): “if Peter were indeed the leader of the Church, we would expect to find much material about his leadership role in the New Testament, at least in kernel form, if not explicitly.” . . .

As for the nature of a “cumulative argument,” what Jason doesn’t seem to understand is that all the various evidences become strong only as they are considered together (like many weak strands of twine which become a strong rope when they are woven together). . . . many of the other [proofs] are not particularly strong by themselves, but they demonstrate, I think, that there is much in the New Testament which is consistent with Petrine primacy, which is the developmental kernel of papal primacy.

The reader ought to note, also, that in the original paper I wasn’t claiming that these biblical indications proved “papal supremacy” or “papal infallibility” (i.e., the fully-developed papacy of recent times). This is important in understanding exactly how I viewed the evidence. . . .

None of the things on the list are “irrelevant,” as Scripture itself is not “irrelevant,” and does not record tidbits of information for no reason. It is inspired; God-breathed, after all. God doesn’t give us useless information. These factors are relevant as indications consistent with the leadership role of Peter. There were many other leaders in the early Church as well, but only one preeminent leader. It is like talking about the Speaker of the House or the Senate majority leader [in American government]. They’re leaders, too, but the President holds a higher office than they do.

I defended my original article at great length in all my replies to Jason. And I will do so again in this multi-part article.

F. F. Bruce, the well-respected Protestant biblical scholar, made a similar point to mine, about Peter’s centrality and importance:

A Paulinist (and I myself must be so described) is under a constant temptation to underestimate Peter . . .

An impressive tribute is paid to Peter by Dr. J. D. G. Dunn towards the end of his Unity and Diversity in the New Testament [London: SCM Press, 1977, 385; emphasis in original]. Contemplating the diversity within the New Testament canon, he thinks of the compilation of the canon as an exercise in bridge-building, and suggests that

it was Peter who became the focal point of unity in the great Church, since Peter was probably in fact and effect the bridge-man who did more than any other to hold together the diversity of first-century Christianity.

Paul and James, he thinks, were too much identified in the eyes of many Christians with this and that extreme of the spectrum to fill the role that Peter did. Consideration of Dr. Dunn’s thoughtful words has moved me to think more highly of Peter’s contribution to the early church, without at all diminishing my estimate of Paul’s contribution. (Peter, Stephen, James, and John, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1979, 42-43)

Elsewhere, four years later, Bruce observed:

And what about the “keys of the kingdom”? . . . About 700 B.C. an oracle from God announced that this authority in the royal palace in Jerusalem was to be conferred on a man called Eliakim . . . (Isa. 22:22). So in the new community which Jesus was about to build, Peter would be, so to speak, chief steward. (F .F. Bruce, The Hard Sayings of Jesus, Downers Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 1983, 143-144)

James Dunn, himself no mean Bible scholar, backs up my overall point quite nicely, too:

So it is Peter . . . who was probably the most prominent among Jesus’ disciples, Peter who according to early traditions was the first witness of the risen Jesus, Peter who was the leading figure in the earliest days of the new sect in Jerusalem, but Peter who also was concerned for mission, and who as Christianity broadened its outreach and character broadened with it, at the cost to be sure of losing his leading role in Jerusalem, but with the result that he became the most hopeful symbol of unity for that growing Christianity which more and more came to think of itself as the Church Catholic. (Unity and Diversity in the New Testament, London: SCM Press, 1977, 385-386)

Many prominent Protestant scholars and exegetes have agreed that Peter is the Rock in Matthew 16:18, including Henry Alford, (Anglican: The New Testament for English Readers, vol. 1, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker, 1983, 119), John Broadus (Reformed Baptist: Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Judson Press, 1886, 355-356), C. F. Keil, Gerhard Kittel (Lutheran: Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, vol. VI, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1968, 98-99), Oscar Cullmann (Lutheran: Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr, 2nd rev. ed., 1962), William F. Albright, Robert McAfee Brown, and more recently, highly-respected evangelical commentators R.T. France, and D.A. Carson, who both surprisingly assert that only Protestant overreaction to Catholic Petrine and papal claims have brought about the denial that Peter himself is the Rock.

That’s nine so far. Here are some more:

10) New Bible Dictionary (editor: J. D. Douglas).

11) Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1985 edition, “Peter,” Micropedia, vol. 9, 330-333. D. W. O’Connor, the author of the article, is himself a Protestant.

12) New Bible Commentary, (D. Guthrie, & J. A. Motyer, editors).

13) Peter in the New Testament, Raymond E Brown, Karl P. Donfried and John Reumann, editors, . . . a common statement by a panel of eleven Catholic and Lutheran scholars.

14) Greek scholar Marvin Vincent.

If Peter was the Rock, as all these eminent Protestant scholars believe, then the argument is a straightforward logical one leading to the conclusion that Peter led the Church, because Jesus built His Church upon Peter. If there was a leader of the Church in the beginning, it stands to reason that there would continue to be one, just as there was a first President when the laws of the United States were established at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Why have one President and then cease to have one thereafter and let the executive branch of government exist without a leader?

Catholics are, therefore, simply applying common sense: if this is how Jesus set up the government of His Church in the beginning, then it ought to continue in like fashion, in perpetuity. Apostolic succession is a biblical notion. If bishops are succeeded by other bishops, and the Bible proves this, then the chief bishop is also succeeded by other chief bishops (later called popes). Thus the entire argument (far from being nonexistent, as Jason would have us believe) is sustained and established from the Bible alone.

To conclude this introduction, I cite the great Lutheran scholar Oscar Cullmann:

Just as in Isaiah 22:22 the Lord puts the keys of the house of David on the shoulders of his servant Eliakim, so does Jesus hand over to Peter the keys of the house of the kingdom of heaven and by the same stroke establishes him as his superintendent. There is a connection between the house of the Church, the construction of which has just been mentioned and of which Peter is the foundation, and the celestial house of which he receives the keys. The connection between these two images is the notion of God’s people. (Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr, Neuchatel: Delachaux & Niestle, 1952 French ed., 183-184)

***

The present study is, first, an extensive and elaborate refutation of a famous Catholic article by Dave Armstrong, which today is in practically all Catholic websites that, in Brazil and in the world, repeat and disseminate a list of 50 “proofs” of the primacy of Peter.

Glad to hear it’s being spread far and wide in Brazil! Lots of Bible going out . . .

It was only after a long time that I decided to elaborate a rebuttal to that article, not only answering all of Armstrong’s points, but also carrying out 205 proofs against the primacy of Peter, which largely refute all the supposed “evidence” that he found in isolation in the Bible.

A cumulative case from all over the New Testament is the very opposite of “in isolation.” It’s systematic theology. Whether he has refuted my argument remains to be seen. Keep reading, folks, and get ready for a “long ride”! It always takes much more “ink” to refute errors than it does to state them. And repeating errors over and over makes them no less false. One could say “2 + 2 = 5” all day long and it wouldn’t be any less false than it was the first time one said it.

To show that the biblical gospel is not formed by one or another isolated passage that cannot support doctrine, I sought to show a much greater biblical content, clearly demonstrating that Dave’s study was extremely arbitrary and that it absolutely ignored the total content of the Scriptures that vigorously repudiate all his attempts.

Nonsense; but an “E for effort . . .”

Without further ado, I will go over the 205 proofs below found throughout Scripture, broken down especially into four main points:

1. Peter’s supposed supremacy over the other apostles in general.

2. Peter’s supposed supremacy over John.

3. Peter’s supposed supremacy over Paul.

4. Peter’s supposed primacy in Rome for 25 years.

After all this, I believe that there will be no more people left who prefer to be clubbed with their isolated biblical passages. Anyone who analyzes the New Testament as closely as I did before composing the present study can easily see how what the Bible overthrows most is the supposed “primacy of Peter.” Read and have fun. The peace of Christ be with all brothers.

Peace and joy of Christ to Lucas and all. May the best argument prevail and may God open our eyes, give us all an open mind and heart, and lead and guide us into the fullness and splendor of biblical truth and revelation, wherever it “goes”. Kick your socks off, find a nice easy chair, and enjoy the “ride.” I know I will enjoy writing this. I hope readers enjoy reading it too.

Evidence that Peter did not exercise primacy over the other apostles

1. The disciples asked “who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (Mt.18:1). Jesus, however, did not take the opportunity to say that it was Peter; quite the opposite! If Peter exercised primacy among the apostles, it would have been no problem for Jesus to end the question right away by answering as Catholics openly declare – that it is Peter, and that’s it!

This is a silly and frivolous, unserious argument. The whole point of the passage is that this was an instance of presumptive arrogance, pride, and spiritual immaturity among two disciples: to be fighting about who was the “greatest” disciple. Jesus cuts right through the pride, stating, “Whoever humbles himself like this child, he is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 18:4). He reiterates later: “He who is greatest among you shall be your servant; whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted” (Mt 23:11-12).

The two disciples in question knew they were wrong, since on one occasion Jesus asked them what they were “discussing” and the text says “they were silent; for on the way they had discussed with one another who was the greatest” (Mk 9:33-34). Jesus said: “he who is least among you all is the one who is great” (Lk 9:48). It was James and John who were the disciples who talked like this: as we know from other passages (and the anger of the other ten against them):

Matthew 20:20-21, 24 (RSV) Then the mother of the sons of Zeb’edee came up to him, with her sons, and kneeling before him she asked him for something. [21] And he said to her, “What do you want?” She said to him, “Command that these two sons of mine may sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your kingdom.” . . . [24] And when the ten heard it, they were indignant at the two brothers.

Mark 3:17 James the son of Zeb’edee and John the brother of James, whom he surnamed Bo-aner’ges, that is, sons of thunder;

Jesus gave them that nickname because these were the two impulsive characters who wanted to kill people with fire because they weren’t receptive to Jesus:

Luke 9:53-55 but the people would not receive him, because his face was set toward Jerusalem. [54] And when his disciples James and John saw it, they said, “Lord, do you want us to bid fire come down from heaven and consume them?” [55] But he turned and rebuked them.

Even tempestuous Peter never said anything that stupid. So to see these passages with their clear intent (James and John were spiritually immature and prideful: apparently inherited from their mother), and to make out that this would supposedly be a golden opportunity for Jesus to say, “Peter is the greatest among you!” is just plain dumb. He’s not going to rebuke the very notion as spiritually prideful and then provide Peter as the example of spiritual pride (??!!). That makes no sense whatsoever.

Besides, Catholics would never say that Peter was the “greatest” anyway. He was simply the leader of the disciples and the first pope. The greatest person was arguably the sinless and immaculate Blessed Virgin Mary. But of course she was too humble to speak in those terms (“I am the handmaid of the Lord . . . he has regarded the low estate of his handmaiden”: Lk 1:38, 48). It’s Elizabeth who praises her: “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!” (Lk 1:42), but Mary immediately gives all the glory to God (Lk 1:46-55).

Some of this can likely be explained by petty jealousy, as Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers, commenting on Matthew 18:1 speculates:

We may well believe that the promise made to Peter, and the special choice of the Three for closer converse, as in the recent Transfiguration, had given occasion for the rival claims which thus asserted themselves. Those who were less distinguished looked on this preference, it may be, with jealousy, while, within the narrower circle, the ambition of the two sons of Zebedee to sit on their Lord’s right hand and on His left in His kingdom (Matthew 20:23), was ill-disposed to concede the primacy of Peter.

Talk about “isolating” passages and having no clue about context . . . Lucas is off to a very poor start. See how much writing it took to properly and thoroughly refute a lousy argument?

2. The fact that the disciples disputed among themselves as to which of them was the greatest shows us that there was no primacy among them, not even after Mt.16:6 (note that the dispute came after that, in Mt.18:1). ). If the disciples had understood Jesus’ statement in Matthew 16:16 (or any other) as an indication of Peter’s superiority over the others, there would be no such dispute, nor would it be necessary to ask Jesus “which of them was the greatest”, since it was already decided that it was Peter! That would make as much logic as a Catholic asking about who has more dominion, the pope or those below him. The very fact that this question is raised already shows us that there was no such primacy, and even more the fact that Jesus denied it further accentuates this fact.

This is equally silly, because there are various meanings and applications of “greatest”: not simply an application to the pope and no one else. Lucas assumes that they could only be talking specifically about being the leader of the disciples. In fact, Jesus stated who was the “greatest” before Matthew 16, and it wasn’t Peter:

Matthew 11:11 Truly, I say to you, among those born of women there has risen no one greater than John the Baptist; yet he who is least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he.

Note that Jesus again made His habitual point about meekness and servanthood. The spiritual pride and immaturity of James and John has no bearing on the primacy of Peter. If indeed they were jealous or envious, as the above Protestant commentator believed, this would actually be evidence in favor of Jesus placing the primacy of ecclesiastical jurisdiction upon Peter. The disciples were often clueless before they received the Holy Spirit on the Day of Pentecost. This is nothing “new” or surprising at all.

3. Jesus stated that the rulers of nations rule over them and important people exercise power over them, but that would not be the case among the disciples (Mt.10:42,43). Now, if Jesus agreed with the dominion that the pope exercises over others (bishops and clerics), then he would have said just the opposite, that is, that Peter was leader among them, just as the rulers of nations were leaders among them.

Jesus’ point was clearly not about mere leadership, but rather, the spirit in which a ruler rules. He is to be the servant of all, just as Jesus was (the perfect example):

Matthew 20:25 But Jesus called them to him and said, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great men exercise authority over them. (cf. Mk 10:42)

Various translations in English bring out His meaning more clearly: “domineer over them” (NASB), “have absolute power . . . [tyrannizing them]” (Amplified, which is designed to stress specific and particular meanings), “foreign rulers like to order their people around . . . have full power over everyone they rule” (CEV), “show off their authority over them” (CEB), etc.

Thus, Jesus was simply saying that Christians must be guided by a different spirit (to act according to His own example), and to not be despots and tyrants, like so many secular leaders are. The ruler was to serve all, not dominate them and be filled with the lust for power. Jesus had no beef against civil (or Church) government per se. When asked about taxes, He casually said, “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s” (Mt 22:21; cf. Mk 12:17; Lk 20:25; Rom 13:6-7). The Apostle Paul appealed to Caesar and his Roman citizenship (which spared him from crucifixion: Acts 25:11-12). He wrote:

Romans 13:1-5 Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. [2] Therefore he who resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. [3] For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of him who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, [4] for he is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain; he is the servant of God to execute his wrath on the wrongdoer. [5] Therefore one must be subject, not only to avoid God’s wrath but also for the sake of conscience.

Peter commanded Christians to “Be subject for the Lord’s sake to every human institution, whether it be to the emperor as supreme, or to governors . . . Honor the emperor” (1 Pet 2:13-14, 17). The emperor at the time he wrote was Nero.

Jesus did say that Peter was the leader of the disciples and His new Church, by making him the Rock upon which that Church was built, giving him (and he alone) the keys of the kingdom, and telling him to “Feed my lambs . . . Tend my sheep . . . Feed my sheep” (Jn 21:15-17), and “strengthen your brethren” (Lk 22:32).

The fact that Christ does not emphasize equality, but rather a contrast, shows us very clearly that, in fact, there would not be a superiority between them: “You know that those who are considered rulers of nations dominate them, and important people exercise power over them. It will not be so among you” (Mk.10:42).

No; it shows that there ought not be a power-hungry, domineering spirit, not that there would be no leadership in the Church. Jesus wasn’t an anarchist. He believed in Church government, just as He believed in civil government.

4. Jesus called Peter “a man of little faith” (Mt.14:31), because he doubted (Mt.14:31).

So did all of the disciples at one time or another. As I said above, this was before they had received the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. Only one, John, was present at the crucifixion. “Then all the disciples forsook him and fled” (Mt 26:56; cf. Mk 14:50), “You will all fall away because of me this night; for it is written, ‘I will strike the shepherd, and the sheep of the flock will be scattered'” (Mt 26:31; cf. Mk 14:27). After they were Spirit-filled, it was a completely different story, and ten of the eleven disciples (minus Judas) died as glorious martyrs.

Let me get this out of the way now and not have to repeat it: Catholics don’t believe that popes are impeccable (sinless), only that they are infallible: and even that is under very specific conditions. So every one of these supposed “disproofs” that notes that Peter was a sinner is simply stating the obvious, and is an irrelevant non sequitur.

5. Peter had the audacity to rebuke Jesus (Mt.16:22), and was rebuked like a demon (Mt.16:23), for acting as a “stumbling block” (Mt.16:23 – NIV; ” cause of scandal” – ARA).

See my answer to #4.

6. Jesus rebuked Peter for “thinking not of the things of God, but only of the things of men” (Mt.16:23).

See my answer to #4. Peter, before he had the Holy Spirit, was understandably concerned about Jesus talking about going to Jerusalem and being killed. He had little understanding about the Messiah having to die for the sins of the world. Once he did, after the Resurrection and Pentecost, then he was a bold and fearless leader, eventually being martyred by being crucified upside down.

We could have a field day pointing out the many sins of anyone before they committed themselves to Jesus as a disciple. We need only look as far as St. Paul, for starters. He recalled later in his life: “I persecuted this Way to the death, binding and delivering to prison both men and women,” (Acts 22:4; cf. 9:4; 22:7; 26:11, 14; Gal 1:13, 23; 1 Tim 1:13). He lamented his own past: “I am the least of the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God” (1 Cor 15:9); “I am the foremost of sinners” (1 Tim 1:15).

But here’s the point, and it applies to both Paul and Peter. Paul wrote: “I received mercy because I had acted ignorantly in unbelief” (1 Tim 1:13). If we’re gonna run down the past sins of apostles, then we should apply this “indignation” equally to Paul. After all, it takes a lot more sinful will to decide to persecute Christians and kill them for the crime of believing that Jesus was Lord and Messiah, than to lose courage in a moment of fear for one’s life, and deny Jesus as a result.

7. It was not only Peter who had the power to “bind or loose”, for this authority was given by Christ to all the disciples (Mt.18:18). Again, Peter appears in the same condition of equality with the other apostles, being that they were invested with the same authority as him!

This is being given the same authority only insofar as they all could impose penances or forgive sins (grant absolution); that is, exercise “binding and loosing.” Every priest and bishop today can do that. It doesn’t make them equal to the pope in authority (or all of the disciples equal to Peter in office). This is some sort of logical fallacy for sure, but I’m too lazy to look it up. But in any event, Peter alone was given the “keys of the kingdom” and this has implications of having a singular office of great authority. Protestant commentators note:

The keys are the symbol of authority, and Roland de Vaux (Ancient Israel, tr. by John McHugh [New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961], 129 ff.) rightly sees here the same authority as that vested in the vizier, the master of the house, the chamberlain of the royal household in ancient Israel. (W. F. Albright and C. S. Mann, The Anchor Bible: Matthew, [Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1971], 196)

This verse [Mat 16:19] therefore probably refers primarily to a legislative authority in the church . . .

The image of keys (plural) perhaps suggests not so much the porter, who controls admission to the house, as the steward, who regulates its administration (Is 22:22, in conjunction with 22:15). (Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background Commentary New Testament [Downer’s Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 1993], 90, 256)

The keys of the kingdom would be comitted to the chief steward in the royal household and with them goes plenary authority. (George Buttrick et al, editors, The Interpreter’s Bible [New York: Abingdon, 1951], 453)

The authority of Peter is to be over the Church, and this authority is represented by the keys. (S. T. Lachs, A Rabbinic Commentary on the New Testament: The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke [Hoboken, New Jersey: Ktav, 1987], 256)

Peter’s ‘power of the keys’ declared in [Matthew] 16:19 is . . . that of the steward . . . . whose keys of office enable him to regulate the affairs of the household. (R. T. France, Matthew: Evangelist and Teacher [Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1989], 247)

The ‘kingdom of heaven’ is represented by authoritative teaching, the promulgation of authoritative Halakha that lets heaven’s power rule in earthly things . . . . Peter’s role as holder of the keys is fulfilled now, on earth, as chief teacher of the church. (M. Eugene Boring, Matthew, in Pheme Perkins et al, editors, The New Interpreter’s Bible, vol. 8 [Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press, 1995], 346)

Just as in Isaiah 22:22 the Lord lays the keys of the house of David on the shoulders of his servant Eliakim, so Jesus commits to Peter the keys of his house, the Kingdom of Heaven, and thereby installs him as administrator of the house. (Oscar Cullman, Peter: Disciple, Apostle, Martyr, translated by Floyd V. Filson [Philadelphia: Westminster, 1953], 203)

8. Peter lacked spiritual insight into the meaning of the parable (Mt.15:15), as did the multitude.

See my answer to #4. Non sequitur.

9. Peter was again rebuked by Jesus for not being able to watch with him even one hour (Mt.26:40).

See my answer to #4. Non sequitur.

10. While Judas was the only disciple who put Jesus to death, Peter was the only disciple who publicly denied Jesus in his death (Mt. 26:69,70).

See my answer to #4. Non sequitur.

11. Peter continued to deny Jesus, even after cursing and swearing (Mt.26:74).

Peter immediately repented upon hearing the cock crow (Mt 26:75; Lk 22:62). His sin and moment of weakness — due to a rational fear for his life in that terrible circumstance — literally lasted just a few minutes. But Paul’s sins went on for some time, and he was so stubborn that he had to be knocked to the ground and more or less forced to convert to Christ. We need to keep things in perspective.

12. Once again the disciples had argued among themselves as to which was the greatest (Mk.9:33,34 and Mk.10:41,42).

Not all of them: only James and John. See my reply to #1.

Both times, Jesus never points to Peter as this leader, as Catholics bluntly do. On the contrary, he confirms that this would not happen between them (Mk.10:43).

Already answered in my reply to #1. Again, Jesus said in Mark 10:43: “whoever would be great among you must be your servant”. That no more rules out a pope who is a servant of all than it does God the Son, Who served all (“the Son of man came not to be served but to serve”: Mt 20:28; cf. Mk 10:45; “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet”: Jn 13:14). It doesn’t rule out bishops in the Church, which are expressly mentioned in the Bible (Phil 1:1; 1 Tim 3:1-2; Titus 1:7; “office” in Acts 1:20 is also episkopos). Nor does it rule out a “bishop of bishops.” This is very poor argumentation and exegesis.

13. Peter continued to demonstrate his fallibility, asking Jesus to depart from him (Luke 5:8), confessing that he was “a sinful man” (Luke 5:8). He did not stand out for being more holy or righteous than the others! Note the contrast to another disciple, Nathanael, in John 1:45.

See my answer to #4. Non sequitur.

14. According to John’s account, Andrew was the first disciple to follow Jesus, not Peter (Jn.1:40,41). Peter only followed him after Andrew called him (Jn.1:41).

So what? What does the order of being called have to do with anything? Paul was called so late that he didn’t even meet Jesus during His earthly life. Once the twelve were all called and in place as disciples, Peter was clearly their leader. It’s so clear that most Protestants don’t deny it. They simply deny that he was pope, or more specifically, that there was papal succession (i.e., a continuance of the office begun by Peter).

15. The greatest praise of character found in Christ’s words is not directed to Peter, but to Nathanael—a “true Israelite, in whom there is no falsehood” (John 1:45).

See my answer to #4. Non sequitur.

16. Although it is often Peter who goes ahead in answering Christ’s questions, at other times it is not him. For example, in John 11:26 this role is occupied in the person of Thomas, encouraging all the other disciples to go to death for Christ (John 11:16).

This doesn’t defeat my argument, which was: “Peter is often spokesman for the other apostles” (#35). The argument is what it is. Being the spokesman “often” shows that the NT is indicating his leadership: in this one way along with forty-nine others.

17. When the Greeks wanted to address Jesus, they did not go looking for the “leader” Peter as “the mouth of the apostles” to communicate Jesus. On the contrary, they preferred to address Philip (Jn.12:20). Curiously, he also did not bother to go to the “leader” Peter, but to Andrew (Jn.12:22). Nor was he concerned to transmit to the “leader” Peter, but he brought the message to Jesus (Jn.12:22). Again, any authority of Peter over the other disciples is unknown!

It doesn’t necessarily mean anything. They simply wanted to see Jesus, saw one of His disciples, and asked him to lead them to Jesus. Philip didn’t have to go to Peter to figure out where Jesus was. Andrew was probably simply close at hand, so Philip may have asked him something like, “hey these guys want to see Jesus, do you think it’s okay?” I don’t see that Peter had to be involved every time someone wants to see Jesus. This is irrelevant, as to His leadership.

18. Jesus said that “no one sent is greater than the one who sent him” (Jn.13:16). Interestingly, it was not Peter who sent the missionaries of the church, but he himself who received orders from the others and was sent by the apostles: “The apostles in Jerusalem, hearing that Samaria had accepted the word of God, sent Peter and John there”( Acts 8:14). Therefore, according to Christ’s rules (“the one sent is not greater than the one who sent him”), Peter could only be, at most, on an equal footing with the other apostles. Exactly what all the evidence points to!

This doesn’t follow. Jesus made a proverbial-type statement that doesn’t apply literally to every particular that includes the same word, “sent.” Being commissioned or sent doesn’t mean that the one sent is equal or lesser than the ones sending him. If so, then Paul would be no more important or significant than “elders” at the council of Jerusalem who sent him to Antioch (Acts 15:22, 25).

19. It was not Peter “the disciple whom Jesus loved”, but John (John 13:26).

This is plain silly. Virtually all conservative Bible commentators agree that this description was John referring to himself in his Gospel, and — in humility — not naming himself or saying “I”. The phrase only appears in John, four times (13:23; 20:2; 21:7, 20; cf. “the other disciple”: 20:2-4, 8). It means nothing more than that and doesn’t imply preference or favoritism. In the same book, Jesus stated to the collective of the disciples that He “loved” all of them (Jn 13:34; 15:12).

20. It was not Peter who reclined in Jesus’ bosom, but John (Jn.13:26; Jn.13:25).

So what? John happened to be able to sit next to Jesus at the Last Supper. Peter may have been on Jesus’ other side, for all we know. But this proves nothing, either way.

21. Jesus denies the truth of Peter’s statement in John 13:37. In addition, it predicts its denials that would occur in the sequence (Jn.13:37,38).

See my answer to #4. Non sequitur. But of course, later on, Peter did lay his life down for Jesus, and was crucified upside down. So Jesus predicted that Peter wouldn’t lay down his life for Jesus right before the crucifixion, but he also predicted his later martyrdom:

John 21:18-19 Truly, truly, I say to you, when you were young, you girded yourself and walked where you would; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will gird you and carry you where you do not wish to go.” [19] (This he said to show by what death he was to glorify God.) . . .

22. It is Thomas who asks for guidance on the Way (Jn.14:5), leading Christ to make the emphatic statement known from John 14:6, that he was “the way, the truth and the life” (Jn.14 :6).

So Thomas asked a question: big wow! How does that imply that he was the leader of the disciples?

23. It is Philip who asked Jesus to reveal the Father (Jn.14:8).

See the previous reply.

24. It is Judas (not the Iscariot) who asks about the manifestation of Christ in our lives (Jn.14:22). Again we see that Peter was far from being one-on-one among all the times that someone takes the floor!

It’s irrelevant. I said that Peter “often” took the lead; not always. And that is significant. It doesn’t have to be 100% / every time / no exceptions, for it to have force as an argument, together with 49 other ones: all pointing in the same direction.

25. Jesus entrusted his mother, Mary, to the care of the beloved disciple, John, and not to Peter (Jn.19:26,27). This must sound even stronger for Catholics, who elevate Mary’s titles to the highest levels, considering her “mother of the Church”. Therefore, according to the same logic, it was John who took care of the “mother of the Church”, not Peter!

Again, this simply has no bearing on whether Peter was leader and pope or not. Jesus probably chose John for this because he was the only disciple there at the cross, with Mary, and Jesus wanted to say such a thing to Mary (and John) in person.

26. Peter does not appear at the foot of the cross, like the apostle John, and some women described in John 19:25, who persevered to the end for Christ’s sake and did not give up following him even at the foot of the cross!

See my answer to #4. Non sequitur.

27. The first of the disciples to arrive at the tomb was John, not Peter (Jn.20:4).

So what? All this means is that he could run faster. What does that have to do with being pope? All popes have to be the fastest runners at the Olympics? What’s interesting here is how John acted when he got there first. He didn’t go in the tomb. He waited for Peter, who did go in (Jn 20:5-8). After Peter did that, John followed. It seems pretty clear that this is deference to a leader.

28. It was not Peter alone who ordained the elders, but all the twelve, gathering all the disciples together (Acts 6:2).

29. Peter did not take it upon himself to choose the “seven men of good testimony” ([Acts].6:3,4), but the apostles in common agreement said to “choose among you” (v.3) the men who should be selected. [note: Lucas’ original mistakenly had John 6:3-4 as the cited verse]

Ordination isn’t the function of the pope alone. This doesn’t prove Peter wasn’t pope or a “proto-pope.”

30. Years later, Peter once again continued to demonstrate his reliability, now also in doctrinal aspects, considering certain foods as “an unclean and profane thing” (Acts 10:15), when Jesus himself had “declared all foods clean” (Mark 7:19)!

In Mark 7:19, it’s the author, Mark, who made the statement, “Thus he declared all foods clean”. This wasn’t stated in explicit terms by Jesus to the hearers, and so the dietary laws didn’t formally change yet. Therefore, Jewish Christians continued to follow the Mosaic dietary laws until the council of Jerusalem, which declared: “For it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us to lay upon you no greater burden than these necessary things: that you abstain from what has been sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled and from unchastity . . (15:28-29).

It was Peter leading, but in conjunction with the apostles and elders (precisely like popes and bishops in ecumenical councils) declaring the official change regarding dietary laws, with the express consent of the Holy Spirit. Peter had received the vision from God in Acts 10, that was actually followed by the Council. We don’t even have the recorded words of Paul at this council, and he went out loyally proclaiming its “Peter-originated and recommended” decision on his missionary journeys (Acts 16:4).

31. Peter equaled Cornelius, placing himself in the same position as a man, not “above” him (Acts 10:25,26).

Yes; as human beings, because Cornelius “fell down at his feet and worshiped him” (10:25). Peter pointing out that he was a man like Cornelius and not to be worshiped has no relevance to whether he was pope. No pope (being a man) should be worshiped, either. This is the dumbest and most laughable objection so far. Pathetic . . .

32. Peter rejected the act of prostrating themselves before him (Ac.10:25,26). Popes, on the other hand, accept all types of people who constantly prostrate themselves at their feet and kiss their hands! What a difference between Peter and the popes! While Peter set an example for Christians to follow, the popes (usurping Peter’s place) accept any and all “reverence” that Peter never accepted!

This is equally ridiculous. Popes accept acts of veneration, not worship, precisely as occurs in Scripture itself:

1 Chronicles 29:20 Then David said to all the assembly, “Bless the LORD your God.” And all the assembly blessed the LORD, the God of their fathers, and bowed their heads, and worshiped [shachah] the LORD, and did obeisance [shachah] to the king.

Genesis 27:29 Let peoples serve you, and nations bow down [shachah] to you. Be lord over your brothers, and may your mother’s sons bow down [shachah] to you. . . .

This is Isaac’s blessing of Jacob.

Genesis 42:6 Now Joseph was governor over the land; he it was who sold to all the people of the land. And Joseph’s brothers came, and bowed themselves [shachah] before him with their faces to the ground.

King Nebuchadnezzar “fell upon his face, and did homage to Daniel” (Dan 2:46; cf. 8:17). The Philippian jailer “fell down before Paul and Silas” (Acts 16:29). Men (apostles) are venerated in the New Testament. The Greek for “fell down before” in Acts 16:29 is prospipto (Strong’s word #4363). It is also used of worship towards Jesus in five passages (Mk 3:11; 5:33; 7:25; Lk 8:28, 47). So why didn’t Paul and Silas rebuke the jailer? I submit that it was because they perceived his act as one of veneration (which is permitted) as opposed to adoration or worship, which is not permitted to be directed towards creatures. Note that the word “worship” doesn’t appear in the above five passages, nor in Luke 24:5 or Acts 16:29. When “worship” [proskuneo] does appear in connection with a man or angel, it isn’t permitted, as in Acts 10:25-26 (St. Peter and Cornelius).

Thus, we see the same in Revelation 19:10 and 22:8-9, because St. John mistakenly thought the angel was Jesus, and so tried to worship / adore the angel. The same thing happened when men thought that Paul and Barnabas were Zeus and Hermes and “wanted to offer sacrifice.” They were rebuked, as mistaken (Acts 14:11-18).

Is all that idolatry, according to the prohibitions of “bowing down” (Ex 20:5; Lev 26:1; Dt 5:8-9; and Mic 5:13). No. All of those passages are strictly about conscious “graven image” idols, meant to replace God. One mustn’t bow to them. But this is obviously not a prohibition of all bowing and veneration, or else the passages above would be presented in the Bible with disapproval (there is not the slightest hint of of that).

33. It was not the church at Rome that sent Paul and Barnabas to Antioch (remember again John 13:16), but the “church in Jerusalem” (Acts 11:22). Taking into account the Catholic argument that Peter was bishop of Rome, and the assumption that Rome (like Peter) exercised primacy over other local communities, this fact points much more to the supremacy of the church in Jerusalem, further overturning this myth. Catholic. Of two, one: Either Rome was not greater than Jerusalem (and therefore Peter was not greater than James or the bishop who ran the church in Jerusalem), or Peter was not bishop in Rome!

This was only one point of time, and fairly early on. Jerusalem was the focus of attention at first; hence, the council of Jerusalem (led by Peter) was an event carrying sublime authority. That will change drastically after Jerusalem is sacked and destroyed by the Romans, not long after, in 70 AD. Most historians agree that Peter eventually resided in Rome and was killed there. Not all think he was the first Roman bishop, but that usually depends on one’s theological and ecclesiological beliefs. Commissioning / sending or ordaining people was usually done on the local level in the early days. None of this should surprise us, and certainly none of it has relevance to Peter’s office.

34. It was not Peter who sent his “subjects”, but he himself received orders and instructions from others (Acts 8:14). He was sent in the same way as Barnabas (Acts 11:22) and then Judas and Silas (Acts 15:22), who are sent later. There is no indication that Peter is solely responsible for things or a kind of “mandatory” of the Church! If Peter were the leader of the church, how could he himself be sent to Samaria with John by the church, instead of him being at the head of sending missionaries?

This is the same fallacy, repeated. Being “sent” is no big deal. Several times elders of a local church “sent” apostles. This was true both with Peter and Paul. Lucas is wrongly assuming all these things, and then shooting them down, as if they have any relevance to our present topic. They do not.

35. Peter was not the only one who had the “keys”, for Paul and Barnabas “opened the door of faith to the Gentiles” (Acts 24:27), all the apostles had the authority of the keys to “bind and loose” in Matthew 18:18, and the Pharisees themselves held it, but did not use it correctly (Luke 11:52).

“Keys of the kingdom” was a technical term, referring back to Isaiah 22 (as many Protestant commentators agree). They were only given to Peter. Acts 24:27 has nothing to do with that. Nor was it applied to the other disciples in Matthew 18:18 because the privileges of the key-bearer were more extensive and exclusive than the powers of “binding and loosing”, as I alluded to above.

36. The greatest Council of the early Church was not held in Rome, but in Jerusalem (Acts 15:2). If Rome was the seat of Peter, and Peter was the “prince of the apostles”, then logically it should be the most suitable place to be the seat of such a Council. The fact that this only took place in Jerusalem shows us that either Peter was never in Rome as pope, or else he did not in fact have any authority at a higher level than the other apostles.

Jesus concentrated on the Jews first, then intended for His Church to reach out to the Gentiles. Everything began in Galilee and Jerusalem, so that’s why the council was there. But Jerusalem was soon to be almost utterly destroyed, so by necessity, the “center” would have to be somewhere else. It made sense in God’s providence to make this location the seat of the Roman Empire.

37. Paul and Barnabas went to deal with this matter with “the apostles and elders” (Acts 15:2), not with Peter in a singular sense.

It was the model of the later ecumenical councils: apostles and elders (later, bishops), presided over by the pope. It perfectly anticipates later Catholic history and ecclesiology.

38. Peter was not the one who opened the Council, nor the one who closed it, not even the one who had the most important word!

39. It was not Peter who first rose to settle the matter with his “gift of infallibility”, for he only said something “after much discussion” (Acts 15:7).

40. Peter, when speaking, did not declare himself as “pope”, nor as exercising primacy over others, nor as the only one who had infallibility. On the contrary, he only emphasizes his ministry among the Gentiles (Acts.15:7) in terms of his various missionary journeys (Acts.9) through Samaria (Acts.8:25), Lydda (Acts.9:32), Caesarea (Ac.10:1), Joppa (Ac.10:5), Antioch (Gal.2;11). He does not claim to be a “universal bishop”, but only points out a missionary ministry among the Gentiles!

41. It was the “apostles and elders” (Acts 15:6) who dealt with this matter. Again, Peter’s sole supremacy is unknown!

42. It was James who presided over the Council of Jerusalem. The entire letter sent to the Gentiles was based entirely on the words of James, not Peter (Acts 15:19-21).

The text doesn’t really say who “opened” it. But it’s nothing unusual for bishops / elders to vote on such matters. That’s how it was with recent papal declarations that were infallible. Bishops were heavily consulted, since the pope wanted to act in concert with them. So either that happened here, or the elders / apostles as a group decided to call the council.

Peter (in the presence of Paul, James, and other apostles) was the first speaker who was named, and one of only two persons who had their words recorded. Peter didn’t have to declare himself the pope. He noted how he was in the forefront of the issue being discussed: “God made choice among you, that by my mouth the Gentiles should hear the word of the gospel and believe” (15:7) and recommended loosening the Mosaic law in the case of Gentile converts.

He had been the first to oversee the first Gentile Christians who were baptized (Acts 10:44-48). Peter acted with that authority, and everyone knew his background as the leader of the twelve disciples. That’s why Paul went to Jerusalem specifically to see Peter for fifteen days in the beginning of his ministry (Gal 1:18).

After Peter spoke (15:7-11), no one disagreed with him (“And all the assembly kept silence”: 15:12). Then after Barnabas and Paul gave their unrecorded report, James, the local bishop (who appears to preside over the council’s proceedings because of that), refers back to Peter’s words (15:14), backs them up with Old Testament Scripture (15:15-18) and then suggests a particular application of Peter’s words (15:20), which was followed in the conciliar decision (15:28-29).

We certainly wouldn’t expect to see a full-blown papacy at this very early stage, because the doctrine developed, just as every other one did (all taking hundreds of years) — it was the same with bishops and the canon of the Bible and even the Holy Trinity — , but what we see here is perfectly compatible with the seeds or kernels of the later fully developed papacy.

43. When James spoke, everyone was silent (Acts 15:13).

That was actually 15:12, and it was after Peter spoke, not James. I thank Lucas for confirming one of my arguments. If he thought it was significant if indeed silence had occurred after James’ speech, then he must think so if it happened after Peter talked (which is the actual case). Glad to find a rare agreement!

44. It was James who closed the Council, not Peter. When asked about all the fundamental points by which we can identify someone who presides over an assembly, James perfectly fills in all the questions: Who has the final say? James. Who gave the verdict? James. Whose suggestion was decided as the very letter that would be sent to the Gentiles? James! Peter’s role in this Council cannot be remotely compared to the leadership of James! This knocks down Peter’s chances of being pope, for then he would himself preside over the Council, and make use of his “infallibility” to decide the matter!

Per my argument above, it appears to me that they sort of jointly preside or work closely together, at any rate. James spoke last because he was the local host-bishop. Early ecclesiology often can’t be put in a nice little package and wrapped with a bow. All sides tend to project their own views in this area onto the past. It’s best that we all admit this. Hence, I wrote in my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism:

As is often the case in theology and practice among the earliest Christians, there is some fluidity and overlapping of these three vocations [bishop, elder, and deacon] (for example, compare Acts 20:17 with 20:28; 1 Timothy 3:1-7 with Titus 1:5-9). But this doesn’t prove that three offices of ministry did not exist. For instance, St. Paul often referred to himself as a deacon or minister (1 Corinthians 3:5, 4:1, 2 Corinthians 3:6, 6:4, 11:23, Ephesians 3:7, Colossians1:23-25), yet no one would assert that he was merely a deacon, and nothing else. Likewise, St. Peter calls himself a fellow elder (1 Peter 5:1), whereas Jesus calls him the rock upon which He would build His Church, and gave him alone the keys of the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:18-19). These examples are usually indicative of a healthy humility, according to Christ’s injunctions of servanthood (Matthew 23:11-12, Mark 10:43-44). (Appendix Two: “The Visible, Hierarchical, Apostolic Church“, 252)

45. The final opinion was not from Peter, but from the “apostles, elders and the whole church” (Acts 15:22) in general. It was they who sent Paul and Barnabas to Antioch (Acts 15:22) with the answer, not Peter.

46. Also the letter sent to the Gentiles with the description of the decision taken on the part of the leadership of the Church has nothing to do with any primacy of Peter, nor does it suggest this. He only limits himself to saying that they were “the brethren apostles and presbyters” (Acts 15:23), without making an average or particular status for Peter as the “ultimate leader” of the Church.

Correct on both counts. This is very early, only slightly developed ecclesiology. But it’s still far closer to Catholicism than any form of Protestantism. Sola Scriptura doesn’t leave any room for an infallible council, that reached a decision binding upon all the Christians around, accompanied by the words: “it has seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” (15:28). That’s Orthodox or Catholic theology, and even in Orthodoxy, they believe in seven ecumenical councils, and then no more occur.

Christians were bound to the decision, as we know from Acts 16:4: “As they [Paul and Silas] went on their way through the cities, they delivered to them for observance the decisions which had been reached by the apostles and elders who were at Jerusalem.” Sola Scriptura simply has no place for such a thing, because it holds that only Scripture is infallible and the standard for the rule of faith. The Jerusalem council utterly contradicts that, and is only one of scores of biblical objections to sola Scriptura.

47. Many years later, Paul was still unconcerned about visiting the church in Rome, but he was determined to “make haste to Jerusalem” (Acts 20:16). If Rome and not Jerusalem were the seat of Christianity, where Peter acted as “pope”, Paul would certainly be in a hurry to get to Rome, not Jerusalem!

Obviously, this was before 70 AD, as explained.

Furthermore, we see that Paul went to Jerusalem to visit James (Acts 21:18).

This was obviously a “missions report” having to do with what was decided at the Jerusalem council. James was there because he was the bishop of Jerusalem. Peter would have almost certainly been evangelizing somewhere else. And so the text says: “he related one by one the things that God had done among the Gentiles through his ministry” (21:19). This hearkens back to the time right before and during the council:

Acts 14:27 And when they arrived, they gathered the church together and declared all that God had done with them, and how he had opened a door of faith to the Gentiles.

Acts 15:3-4 So, being sent on their way by the church, they passed through both Phoeni’cia and Sama’ria, reporting the conversion of the Gentiles, and they gave great joy to all the brethren. [4] When they came to Jerusalem, they were welcomed by the church and the apostles and the elders, and they declared all that God had done with them.

Acts 15:12 . . . and they listened to Barnabas and Paul as they related what signs and wonders God had done through them among the Gentiles.

If Peter were the ultimate authority to which Paul owed allegiance, he would be in a hurry to get to Rome and speak with Peter, a fact in which the Bible is simply silent from beginning to end!

Well, when Paul visited Peter, he was still in Jerusalem. But that doesn’t wipe out the fact that he consulted with him to get the “go ahead” for his ministry and work:

Galatians 1:18-19 Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas, and remained with him fifteen days. [19] But I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother. (cf. 2:9: “and when they perceived the grace that was given to me, James and Cephas and John, who were reputed to be pillars, gave to me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship, that we should go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised”)

48. When Peter was released from prison, he told them to report this to James (Acts 12:17), who evidently should have been the first to hear about it.

As the local bishop, yes, that would be perfectly logical. He left word before he went out of town (21:18: “he departed and went to another place”).

49. It is not Peter who is indicated as being “the leader of the sect of the Nazarenes” (Acts 24:5), but Paul.

My RSV Bible says “a ringleader” as opposed to “the ringleader.” How much difference one little word makes! I’ve found only one out of about 60 English translations of Acts 24:5 that has “the ringleader.” So this hardly bolsters Lucas’ case that Paul was regarded as the top leader by Anani’as’ “spokesman, one Tertul’lus” (24:1). “Nice try, but no cigar”: as we say in English.

50. Peter is not appointed as the only pillar of the Church, but shares the place with others (Gal.2:9).

In Galatians 2:9, where Peter (“Cephas”) is listed after James and before John, he is clearly preeminent in the entire context (e.g., 1:18-19; 2:7-8). In ten places in the New Testament (RSV), Peter is listed first whenever he is mentioned along with James and John, and sometimes, in addition to them, other disciples as well:

Matthew 10:2 The names of the twelve apostles are these: first, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother; James the son of Zeb’edee, and John his brother;

Matthew 17:1 And after six days Jesus took with him Peter and James and John his brother, and led them up a high mountain apart.

Mark 5:37 And he allowed no one to follow him except Peter and James and John the brother of James.

Mark 9:2 And after six days Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain apart by themselves; and he was transfigured before them,

Mark 13:3 And as he sat on the Mount of Olives opposite the temple, Peter and James and John and Andrew asked him privately,

Mark 14:33 And he took with him Peter and James and John, and began to be greatly distressed and troubled.

Luke 6:14 Simon, whom he named Peter, and Andrew his brother, and James and John, and Philip, and Bartholomew,

Luke 8:51 And when he came to the house, he permitted no one to enter with him, except Peter and John and James, and the father and mother of the child.

Luke 9:28 Now about eight days after these sayings he took with him Peter and John and James, and went up on the mountain to pray.

Acts 1:13 and when they had entered, they went up to the upper room, where they were staying, Peter and John and James and Andrew, Philip and Thomas, Bartholomew and Matthew, James the son of Alphaeus and Simon the Zealot and Judas the son of James.

Galatians 2:9 is an exception: “James and Cephas and John”. I would guess it is because James was the bishop of Jerusalem. Even so, in the preceding verses (2:7-8) and ones after (2:11-14), only Peter is referred to. Many Protestant commentaries agree about why James was listed first:

Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary James—placed first in the oldest manuscripts, even before Peter, as being bishop of Jerusalem, and so presiding at the council (Ac 15:1-29).

Expositor’s Greek Testament This was probably because as permanent head of the local Church he presided at meetings (cf. Acts 21:18).

Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges James . . . is named first, because the reference is to a special act of the Church in Jerusalem, of which he was president or Bishop. “When St Paul is speaking of the missionary office of the Church at large, St Peter holds the foremost place”. Lightfoot. Compare Galatians 2:7-8 with Acts 12:17; Acts 15:13; Acts 21:18.

Bengel’s Gnomen James . . . is put here first, because he mostly remained at Jerusalem, . . .

Pulpit Commentary James . . . is named first, before even Cephas and John, though not an apostle, as being the leading “elder” (bishop, as such a functionary soon got to be designated) of the Church of Jerusalem; . . .

Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers The way in which St. Paul speaks respectively of St. Peter and St. James is in strict accordance with the historical situation. When he is speaking of the general work of the Church (as in the last two verses) St. Peter is mentioned prominently; when the reference is to a public act of the Church of Jerusalem the precedence is given to St. James.

This relative trifle (which can be easily explained) doesn’t overcome the mountain of evidence I have compiled as to the primacy of Peter.

END OF PART ONE

***

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,000+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing, including 100% tax deduction, etc., see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

***

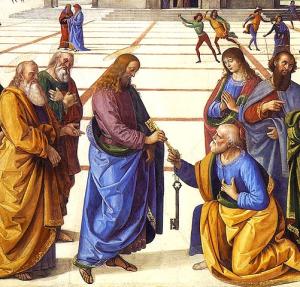

Photo credit: Detail of Christ Handing the Keys to St. Peter (1481-82) by Pietro Perugino (1448-1523) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: Brazilian Protestant apologist Lucas Banzoli takes on my “50 NT Proofs for Petrine Primacy”, with 205 potshots at St. Peter & his primacy. This is Part 1 of my replies.