Response to Orthodox and Protestant Criticisms

From one of the more thoughtful Protestant participants at the Coming Home Network board (in blue) with my replies:

* * * * *

It’s the “specific and legalized approach” that’s the hardest thing or me to embrace about the RCC. That’s not to say that I don’t see the reason for having central authority or accepting the teaching of the magisterium. But in the EO [Eastern Orthodoxy] there is an intriguingly comparable approach which, however, doesn’t put the same emphasis on pinning down everything, defining everything.

There are two ways to look at that. I would say (as a veteran of many discussions with Orthodox on this very thing) that, just as we are described as being overly-rational and legalistic, they could be described as suffering from the opposite problem: being under-rational and insufficiently legalistic.

Arguably, these problems have led to the much greater instance of heresy among the eastern patriarchs in the early centuries (especially Monophysitism and Monotheletism, but also Arianism). It was the very lack of precision and order that the Latin West possessed (and the central papal authority) that led to this.

We’re accused of being so “hyper-rational,” and the targets are often St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas. The criticisms have become so extreme and irrational, that we see, e.g., an absurd statement like the following:

Latin Scholastic theology, emphasizing as it does the essence at the expense of persons, comes near to turning God into an abstract idea. He becomes a remote and impersonal being . . . a God of the philosophers, not the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Joseph. (Bishop Kallistos [Timothy] Ware, The Orthodox Church, New York: Penguin Books, revised 1980 edition, 222)

I could go on and on in response to this ludicrous charge.

First of all, anyone who is familiar with St. Thomas knows that he was not just about minute distinctions and legalism and what-not. He was also quite a mystic and a “devotional” person (especially later in his life). He could combine both things and not see a contradiction. It’s the Catholic “both/and” outlook.

Secondly, the same Church that so highly exalts St. Thomas has an extraordinary mystical tradition, with saints like St. Francis, St. Catherine, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Therese, St. John of the Cross, etc. We don’t feel the need to dichotomize these two strains against each other. The Catholic Church is large enough for both; it rejoices in both. We have both great thinkers and logical analysis and great mystics and mystical reflection (sometimes in the same person). But Orthodox so often have to run down the “rationalistic” or “legalistic” aspects of the Catholic Church. They are exclusivistic insofar as this sort of high-level thinking is frowned upon. We are inclusivistic and welcome both serious, logical thinking and mysticism and personal devotion to God.

Thirdly, while it is running down our “legalism,” Orthodoxy has had a difficult time in opposing modernity and secularism. It is precisely because we define more specifically and logically that we have stood fast against, e.g., divorce and contraception. The Orthodox have not, and so consequently, they allow divorce and they are increasingly caving on contraception, that was regarded as a grave sin in their own circles until essentially the last 40-50 years.

We think very deeply about the nature of true marriage, divorce, and annulment, and so we have maintained the traditional teaching. We have things like Humanae Vitae and NFP, that makes the proper and essential distinctions, so as to not cave on the issue of contraception.

Fourth, there is a certain double standard involved in such criticisms coming from Orthodox, since it was, again, very fine-tuned distinctions in theology in the early centuries of the united Church, that were the reason for the many heresies not overcoming the Christian Church.

Orthodoxy may not care for precise distinctions now, but that was certainly not the case with the many eminent early eastern fathers, such as Athanasius, Gregory Nazianzen, Maximus the Cofessor, John Chrysostom, and so forth. These were every bit as “rational” as western fathers (if not even more so), yet now the very same thought processes are frowned upon, as if one thing were true a thousand years ago and now something else contradictory to it is the case.

Fifth, we see the same incoherence in the case of someone like St. Gregory Palamas (1296-1359). Many Orthodox I’ve come in contact with have completely eschewed the notion of doctrinal development (collapsing it into a caricature of itself, as “evolution of dogma”). But he developed the mystical tradition / practice of hesychasm. Kallistos Ware notes this (it ain’t just my Catholic opinion):

A hesychast is one who in silence devotes himself to inner recollection and private prayer. While using the apophatic language of negative theology, these writers claimed an immediate experience of the unknowable God, a personal union with Him who is unapproachable. How were the two ‘ways’ to be reconciled? How can God be both knowable and unknowable at once? This was one of the questions which was posed in an acute form in the fourteenth century.

. . . how was this vision of Divine Light to be reconciled with the apophatic doctrine of God the transcendent and unapproachable? All these questions concerning the transcendence of God, the role of the body in prayer, and the Divine Light came to a head in the middle of the fourteenth century.

. . . To explain how this was possible, Gregory developed the distinction between the essence and the energies of God. It was Gregory’s achievement to set Hesychasm on a firm dogmatic basis, by integrating it into Orthodox theology as a whole, and by showing how the Hesychast vision of Divine Light in no way undermined the apophatic doctrine of God.

. . . his work shows that Orthodox theology did not cease to be active after the eighth century and the seventh Ecumenical Council. (The Orthodox Church, New York: Penguin Books, 1980 revision, 73, 75-76, 79)

My sense is that by putting a strong emphasis on definitions, the church unintentionally discourages the spontaneous response of the heart to God’s unimaginable love.

I would say it is exactly the opposite, as other commenters have noted. G. K. Chesterton wrote (and while he was still Anglican, by the way, 14 years before he became a Catholic):

And if we took the third chance instance, it would be the same; the view that priests darken and embitter the world. I look at the world and simply discover that they don’t. Those countries in Europe which are still influenced by priests, are exactly the countries where there is still singing and dancing and coloured dresses and art in the open-air. Catholic doctrine and discipline may be walls; but they are the walls of a playground. Christianity is the only frame which has preserved the pleasure of Paganism. We might fancy some children playing on the flat grassy top of some tall island in the sea. So long as there was a wall round the cliff’s edge they could fling themselves into every frantic game and make the place the noisiest of nurseries. But the walls were knocked down, leaving the naked peril of the precipice. They did not fall over; but when their friends returned to them they were all huddled in terror in the centre of the island; and their song had ceased. (Orthodoxy, 1908, ch. 9)

Now I know well that there have been many mystics in the church throughout the ages, so of course this is only a generalization, but as one who from the beginning of my faith life has experienced God in deep mystical ways, it concerns me that so much of what is put forward to help people understand the church has to do with the minutiae of rules.

I don’t deny that there are abuses in practice. That is always the case. People who are not truly following God in a personal way tend to fall back on legalism and mere rules, and cease to operate from the heart and their whole being: heart, soul, will, and mind, just as when people are seriously not getting along, they will fall back on legal intermediaries, rather than plainly talk to each other. But the actual teaching and tradition of the Catholic Church incorporates all of these elements.

For that reason I am deeply grateful to God that He originally drew me to Himself through the nondenominational charismatic movement. By emphasizing God’s deep love for us, and teaching us that the only appropriate response to that love is to love Him back deeply, we were kept focused on the essence of what it means to be a disciple.

That’s good, and my own evangelical background was very similar indeed, but the spiritually mature Christian moves on to serious theology as well, and that can’t be done without serious thinking and utilization of rationality.

Reading the Bible with the intent of learning how to love God more fully, being encouraged to express our love through singing of psalms and other scripture, having our pastors continually emphasize the condition of the heart rather than the observance of the rules – all these firmly grounded me in my relationship to God. I know I would have given up early if I had been confronted with a myriad of rules that I was expected to follow or otherwise be in danger of falling off the path.

Again, this is good, except for the fallacy of pitting these aspects of faith against rules, as if they are antithetical. Many cults that developed out of the Protestant milieu showed what happens when rules and proper theological thinking are cast to the wind or relegated to a “non-required” status, or sort of frowned upon.

As I understand them, the rules are there to describe the boundaries of the path: “observe these rules and you won’t go astray”. But as we know from raising our children, an overemphasis on rules can lead to the child’s internal sense of right and wrong being stunted, because it hasn’t had a chance to be personally exercised, relying instead on external rules. What works better is to have a few simple, clear rules within which the child can learn the subtleties of personal discernment.

I would argue (with some experience myself in raising four children), that both rules and love must exist side-by-side. The love is always there and it is unconditional, and a close relationship. But the rules are also there, so that they have a very clear sense of boundaries and right and wrong. Going to the extreme of having one without the other causes huge problems (that are so obvious I need not even mention them). They should both be there, and the loving parent has to be ready to be firm enough to discipline, to whatever extent is necessary to stop the sinful behavior.

Parents are worried about raising children who will be decent, loving, caring persons, good Christians, and law-abiding. God is concerned with raising children and preparing them ultimately for heaven. If Christians go astray, they go to hell, so this is no small matter. The “discipline” and rules are needed so as we don’t end up in hell.

I’m reminded of the story of King David coming to the tabernacle with his men, who were hungry. They took the showbread and ate it, which of course was forbidden. Yet the lesson of the story is that rules were made for man, and not man for rules.

Exactly. Yet Jesus didn’t reject the Law at all. It was still in force, just developed. Quite to the contrary, He said:

Matthew 5:17-20 Think not that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I have come not to abolish them but to fulfil them. For truly, I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the law until all is accomplished. Whoever then relaxes one of the least of these commandments and teaches men so, shall be called least in the kingdom of heaven; but he who does them and teaches them shall be called great in the kingdom of heaven. For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.

Jesus continued to observe the law. Paul called himself a Pharisee. The early Christians continued to attend synagogue and temple worship.

What I’m sitting with/reflecting on is the perception that the church cares more about rules than about life.

People perceive a lot of different things. But these can often be false perceptions, based on insufficient data. The quintessential example is the ubiquitous “bad nun” childhood stories. Who cares if there was one mean nun at school or something? What does that prove? Nothing I can see, except that, well, there was one mean nun! Would anyone deny that this would be the case somewhere?

The point is that we need to think deeply about this issue and — as you say — the relationship between rules and regulations and rationality (the three “r’s”?) and our personal relationship with God.

We know that’s not true, but my observation from hearing many “ex-Catholics” talk about their faith and their perception of the Catholic Church once they had left revolves around their sense that the RCC was all about rules, whereas their experience in protestant-land was a focus on the experiential knowledge of God rather than on following rules.

Ex-Catholic stories are notoriously inaccurate and skewed. I’ve dealt with those time and again, just as I’ve dealt with several atheists and their deconversion stories away from Christianity. Most of these people — I think it is safe to say — never fully understood (or practiced) their former faith. This is very clear, for example, in the common complaint of former Catholics that they supposedly “never heard the gospel” at Mass. It’s muddleheaded thinking: far more indicative of the confusion of their own brains and spiritual life than of the reality in the Church (though, of course, in individual cases, there can be any number of horror stories with sinners involved).

But I don’t understand the reason for the minutiae of the rules as discussed in some of the threads, or on the various call-in shows I listen to (Catholic Answers Live, etc.).

It’s because life is complex, and the complexity of problems in a complex life require complex answers that sufficiently deal with all the objections that are raised. Of course, one simplifies so that those who aren’t as trained in thinking and as educated can also understand, but that doesn’t rule out the more in-depth explanations for those who require those, and in order to avoid heresies and related falsehoods.

One can make an individual judgment that the Church goes too far in this, but that gets back to the difference between private judgment and belief in an infallible Church, specially guided by the Holy Spirit in order to fully preserve apostolic truth. We have to yield to that at a certain point. We don’t judge the Church, in the final analysis. We accept her teachings in faith, by the grace of God.

However, it’s the condition of the heart that matters to God, and as we’re all well aware, following rules is often strictly external in nature, with no effect on the heart.

Amen! That’s what we teach. Vatican II stressed this with regard to participation in the Mass:

In order that the liturgy may be able to produce its full effects it is necessary that the faithful come to it with PROPER DISPOSITIONS, that their minds be attuned to their voices, and that they cooperate with heavenly grace lest they RECEIVE IT IN VAIN. Pastors of souls must, therefore, realize that, when the liturgy is celebrated, something more is required than the laws governing valid and lawful celebration. It is their duty also to ensure that the faithful take part FULLY AWARE of what they are doing, ACTIVELY ENGAGED in the rite and enriched by it…….Mother Church earnestly desires that all the faithful should be led to that full, conscious, and active participation in liturgical celebrations which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy…….In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy the full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered above all else, for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true Christian spirit. Therefore, in all their apostolic activity, pastors of souls should energetically set about achieving it through the requisite pedagogy. (Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Dec. 4, 1963, ch. 1, I, sec. 11 and II, sec. 14; emphasis added)

So what am I looking for?

What the Church offers.

Just some others to sit in this place of wondering with me – wondering about the nature of man, that on the one hand he needs clear lines to guide him, and on the other hand, he can completely miss where the path is leading by focusing exclusively on the lines.

It’s not “exclusively” on lines. It’s lines and non-lines together. It is avoiding extremes of going too far in one direction and losing sight of other important aspects, and not throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Chesterton again hits the nail on the head when he discusses orthodoxy (i.e., true doctrine, not the Orthodox Church) and creeds:

Here it is enough to notice that if some small mistake were made in doctrine, huge blunders might be made in human happiness.It was the equilibrium of a man behind madly rushing horses, seeming to stoop this way and to sway that, yet in every attitude having the grace of statuary and the accuracy of arithmetic.It is always simple to fall; there are an infinity of angles at which one falls, only one at which one stands. Orthodoxy, ch. 6)

The Christian creed is above all things the philosophy of shapes and the enemy of shapelessness. The condemnation of the early heretics is itself condemned as something crabbed and narrow; but it was in truth the very proof that the Church meant to be brotherly and broad. If the Church had not insisted on theology, it would have melted into a mad mythology of the mystics, yet further removed from reason or even from rationalism; and, above all yet further removed from life and from the love of life. And that is why the Church is from the first a thing holding its own position and point of view, quite apart from the accidents and anarchies of its age. (The Everlasting Man, II-4)

Wondering about God’s promise that he would write the law on our hearts; that Christ’s sacrifice has set us free from slavishly following the law; that God’s will for us can be summed up simply in “love the Lord thy God, and thy neighbor as thyself”.

The pitting of law and grace against each other in many unbiblical ways, is one of the problems of several forms of Protestant theology. False dichotomies abound there. The “new perspective on Paul” theology in Protestant circles (N. T. Wright et al) is turning a lot of this on its head. They understand that not only do Catholics not teach a salvation by works, but that the ancient Jews did not, either. They believed that salvation came by faith, too. But it got distorted among many individuals and schools (just as it does among liberal and nominal Catholics).

Wondering about what the Catholic church can learn from the experience of its members who have converted from other christian traditions, not in terms of truth (because it already has the truth) but in terms, perhaps, of how the truth is imparted.

Tons. I think I use my own experience virtually anytime I write about anything in theology or apologetics. Vatican II is very explicit in noting this.

I know I am speaking about meat here, and not milk, but I’d like to hear from others on this level.

I hope there is enough for you to chew on in my analysis!

I need to hear others who came from protestant backgrounds share what they have found that they can do in the Church to share some of the good things that they brought with them – things like small groups where people live out their commitment to support and help one another on an intimate level; Bible studies and prayer groups where we can encourage one another in our growth in understanding the scripture and in praying effectively; participatory music that’s accessible to all – both music aimed at praise (horizontal) and music aimed at worship (vertical).

All great things . . . Catholics can learn a lot of things from Protestants. I am always very thankful that I was a Protestant because I learned a lot of these things there, that are not so prevalent, sadly, in the Catholic Church; yet are entirely “Catholic,” historically speaking.

It seems to me that by giving a lesser place to the things that stir up a hunger for the immediacy of relationship with God, Catholics are then vulnerable to finding that elsewhere.

Indeed.

By the way, I was very happy to hear someone tell about the program based on Maria Montessori’s methods that is being adopted in churches to teach children about God. That apparently is speaking directly to the need to stir up a hunger for direct relationship with God.

Amen.

***

(originally 9-8-08)

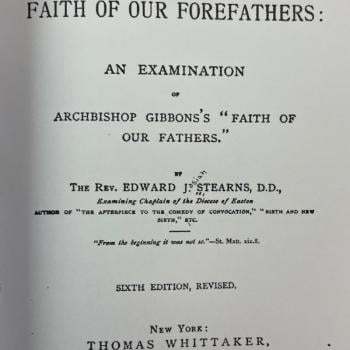

Photo credit: Saint Thomas Aquinas (1605), by Adam Elsheimer (1578-1610) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***